I haven

Archives for March 2007

TT: Straight from the source

Jonatha Brooke, one of my favorite singer-songwriters, has recorded a new album called Careful What You Wish For. She sent this message to her e-mailing list the other day:

I know you’re barraged with email every day. BUT, it occurred to me late last night, gearing up for this pre-order release, that if every one of you reading this (you all did sign up at some point!) bought the new CD here, we’d be able to cover our costs for three months!! No small feat.

So, it’s true, we’re ready to start taking pre-orders for my new record, “Careful What You Wish For.” We’ll start sending them out next week, and of course, I will autograph every single one.

As I’m sure you know, the record business is as tough as it’s ever been. Tower is gone, and most retail stores will only stock the top sellers. So whether you buy the record here, at Amazon or Borders or Barnes and Noble, every sale counts. Spreading the word to your friends and family is incredibly helpful too.

That

TT: Almanac

“There is no trap so deadly as the trap you set for yourself.”

Raymond Chandler, The Long Goodbye

TT: Time capsules

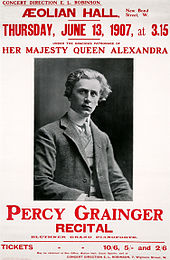

A hundred years ago, Percy Grainger, an eccentric Australian pianist-composer temporarily resident in London, took an interest in English folk songs and decided to go out into the country and collect them. He went to North Lincolnshire in 1905 to attend a local music festival whose events included a folk-song competition. The fliers for the festival described the event as follows:

A hundred years ago, Percy Grainger, an eccentric Australian pianist-composer temporarily resident in London, took an interest in English folk songs and decided to go out into the country and collect them. He went to North Lincolnshire in 1905 to attend a local music festival whose events included a folk-song competition. The fliers for the festival described the event as follows:

Class XII. Folk songs. Open to all. The prize in this class will be given to whoever can supply the best unpublished old Lincolnshire folk song or plough song. This song should be sung or whistled by the competitor, but marks will be allotted for the excellence rather of the song than of its actual performance. It is specially requested that the establishment of this class be brought to the notice of old people in the country who are most likely to remember this kind of song, and that they be urged to come in with the best old song they know.

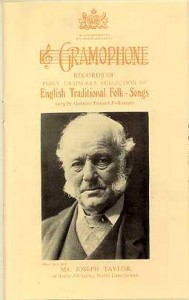

The first prize went to a seventy-two-year-old man named Joseph Taylor who impressed Grainger hugely, not only with the song he sang but with the way he sang it. Grainger later wrote that “his flowing, ringing tenor voice was well nigh as fresh as that of his son…Nothing could be more refreshing than his hale countrified looks and the happy lilt of his cheery voice.”

On another occasion he recalled:

Mr. Joseph Taylor…was neither illiterate nor socially backward. And it must also be admitted that he was a member of the choir of his village (Saxby-All-Saints, Lincolnshire) for over 45 years—a thing unusual in a folksinger. Furthermore his relatives—keen musicians themselves—were extremely proud of his prowess as a folksinger. Mr. Taylor was bailiff on a big estate, where he formerly had been estate woodman and carpenter. He was the perfect type of an English yeoman: sturdy and robust, yet the soul of sweetness, gentleness, courteousness and geniality.

Grainger took down several songs in musical notation from Taylor and the other singers he met that April, and came back to Lincolnshire the following year with a portable phonograph that he used to record their voices. (“He’s learnt that quicker nor I,” one singer said as Grainger played back the song he’d just recorded.) He soon became fascinated to the point of obsession with the songs he collected and the idiosyncratic way in which the people he met sang them, and over the next few years he made dozens of instrumental and vocal arrangements of them.

By that time Grainger was already well known as a concert pianist who wrote music on the side, but these piquant arrangements, some of which became hugely popular, helped make him famous, as did the folk-inspired original compositions he started to produce around the same time. For the rest of his life he would be mainly known as the composer of such engaging miniatures as “Country Gardens,” “Molly on the Shore,” and “Irish Tune from County Derry” (better known as “Danny Boy”).

In 1908 Grainger persuaded the Gramophone Company to record Joseph Taylor in the studio. It was the first time that the voice of a “Genuine Peasant Folksinger” (as the label described Taylor in its promotional material) had ever been commercially recorded for posterity. Taylor didn’t much care for the process, claiming that singing into an acoustical horn was “lahk singin’ with a muzzle on,” but that didn’t stop him from doing his best. He cut a dozen songs, of which nine were released. The original 78s, not surprisingly, sold poorly and soon became rarities—only two complete sets of the seven discs are known to exist—and except for an obscure 1972 LP release known only to folksong specialists, they have long been hard to track down in any format.

In 1908 Grainger persuaded the Gramophone Company to record Joseph Taylor in the studio. It was the first time that the voice of a “Genuine Peasant Folksinger” (as the label described Taylor in its promotional material) had ever been commercially recorded for posterity. Taylor didn’t much care for the process, claiming that singing into an acoustical horn was “lahk singin’ with a muzzle on,” but that didn’t stop him from doing his best. He cut a dozen songs, of which nine were released. The original 78s, not surprisingly, sold poorly and soon became rarities—only two complete sets of the seven discs are known to exist—and except for an obscure 1972 LP release known only to folksong specialists, they have long been hard to track down in any format.

Grainger himself had faded into semi-obscurity well before his death in 1961, but his folk-style pieces continued to be played, and a small but loyal band of influential musicians, among them Benjamin Britten and Frederick Fennell, made brilliant recordings of his music that brought it to the attention of a new generation of listeners and performers, myself among them. Thanks to these performances, as well as John Bird’s 1976 biography, Grainger has come to be widely regarded as a composer of significance, and virtually all of his music is now available on CD. Britten’s 1969 Grainger collection, for instance, was reissued a few years ago, as was Fennell’s legendary 1958 recording with the Eastman Wind Ensemble of Lincolnshire Posy, a six-movement suite for concert band based on some of the songs that Grainger collected in Lincolnshire.

But what about old Joseph Taylor? I’ve long been fascinated by Grainger and his music—the Max Beerbohm caricature I purchased a couple of years ago is a 1913 study of Grainger playing piano for a group of London ladies—and so it followed that I wanted very much to hear Taylor’s 78s. I couldn’t track any of them down until a year and a half ago, when I put out a plea in this space to which one of my trusty readers responded, informing me that Taylor’s version of “Brigg Fair” had been reissued on CD.

I bought it, ripped it, and wrote about it:

From the speakers…came a century-old sound: It was on the fifth of August, the weather fair and fine/Unto Brigg Fair I did repair, for love I was inclined. I listened with wonder to Joseph Taylor’s throaty, ever-so-slightly creaky voice and the fluttering ornaments with which he gracefully decorated the long descending arch of melody.

That was the end of the story—until last week.

For some reason it occurred to me the other day to look up Joseph Taylor on iTunes and see what I might find. To my bemusement and delight, I found seven of the twelve songs Taylor recorded in London in 1908, including “Brigg Fair” and “Creeping Jane,” the very song with which he won the prize that had brought him to Grainger’s attention three years earlier.

You can download any or all of them if you’re curious, and I recommend that you do so, not only for their intrinsic musical value but because they fling wide a tightly shut door. The world in which people like Taylor lived vanished long ago—it was already disappearing fast in 1908—and you will never again be so close to it as during the sixteen and a half minutes it takes to listen to these seven 78 sides.

Ralph Vaughan Williams, another composer who was profoundly affected by his exposure to English folk singers, wrote about them in 1932:

I am telling you not of something clownish and boorish, not even something inchoate, not of the half-forgotten reminiscences of fashionable music mouthed by toothless old men and women, not of something archaic, not of mere “museum pieces,” but of an art which grows straight out of the needs of a people and for which a fitting and perfect form, albeit on a small scale, has been found by those people; an art which is indigenous and owes nothing to anything outside itself, and above all an art which to us today has something to say—a true art which has beauty and vitality now in the twentieth century….

The folk-song is I believe not dead, but the art of the folk-singer is. We cannot, and would not if we could, sing folk-songs in the same way and in the same circumstances in which they used to be sung.

Of course Vaughan Williams was right—which makes it all the more wonderful that you can now use your computer to download records made by a man born in 1832 of songs that he learned as a boy in Lincolnshire, long before anyone had dreamed of such everyday witchcraft.

If that’s not worth seven dollars, I don’t know what is.

UPDATE: To listen to Joseph Taylor’s 1908 recording of “Rufford Park Poachers,” go here.

To download Taylor’s recordings of “Bold William Taylor,” “Brigg Fair,” “Creeping Jane,” “The Gypsy Girl,” “Sprig o’ Thyme,” “The White Hare,” and “Worcester City,” go here.

To order CD transfers of Percy Grainger’s complete solo-piano 78s, including his performances of “Country Gardens,” “Molly on the Shore,” and “Irish Tune from County Derry,” go here.

TT: Almanac

“Like so many aging college people, Pnin had long since ceased to notice the existence of students on the campus.”

Vladimir Nabokov, Pnin

OGIC: Brief, muffled cry

Positively crushed right now by heaps and heaps of work. Project full recovery and return in two weeks when critical deadline has passed. Until then.

TT: Madly industrious

I’ve now changed all of the Top Five and “Out of the Past” picks and updated the “Teachout in Commentary” module, so if you haven’t visited the right-hand column lately, do so.

TT: Saddled up

It took longer than I expected for me to shake off whatever bug it was that laid me low two weeks ago. Nothing short of an ambulance ride is enough to shut me down completely, though, and I’ve been keeping fairly busy despite my intermittent absences from this space.

Among other things, I saw two plays, one of them in the company of Mr. My Stupid Dog, who was in New York for a few days and kindly consented to accompany me last Friday to the Signature Theatre Company