Cy Walter, who died in 1968, specialized in a style of popular piano playing for which there has never been a satisfactory name. Because he and others like him spent most of their lives working in the lounges of high-priced hotels, most people now refer to their kind of music as “cocktail piano,” which is accurate as far as it goes but fails altogether to suggest the elegance and technical wizardry of Walter’s own playing.

I suppose one might call it “cabaret piano,” since he was closely associated with singers like Mabel Mercer, whom he accompanied with exquisite taste, and it’s certainly no coincidence that he figures so prominently in the pages of James Gavin’s Intimate Nights: The Golden Age of New York Cabaret. Walter himself didn’t much care for labels, but when pressed he would call himself “a specialist in show tunes.” For my part, and even though I don’t much care for neologisms, I like to think of the genre in which he worked as “New Yorker music.” Needless to say, the New Yorker I have in mind is the one founded and edited by Harold Ross, a rough-hewn newspaperman from Colorado who by some miracle of grace contrived to bring into being the most sophisticated magazine in the history of American journalism. It didn’t survive him for long, at least not in its original form: William Shawn took it in directions that proved alien to Ross’ tutelary spirit, and today’s New Yorker, for all its virtues, is greatly different in tone and approach from the magazine Ross edited between 1925 and his death in 1951.

Among many other things, Ross’ New Yorker promoted the kind of music performed by the artists chronicled in Intimate Nights. Rogers Whitaker, who covered cabaret (though it wasn’t yet called that) for the magazine, loved Walter’s piano playing and plugged him regularly in the “Goings On About Town” section. Alec Wilder, a New Yorker-endorsed songwriter who also wrote wisely and well about American popular song, contributed a set of liner notes to one of Walter’s albums in which he remarked that “anyone who has heard his own songs played by Cy immediately has a greater respect for his own work.” That is one hell of a compliment, and there were plenty of equally illustrious folk inclined to echo it. The mailing list of fans to whom Walter sent postcards announcing his gigs (it’s preserved in his papers) includes Tallulah Bankhead, Leonard Bernstein, Marlon Brando, Katharine Cornell, Lynn Fontanne, Elia Kazan, Frank Loesser, Agnes De Mille, Arthur Miller, Cole Porter, Jerome Robbins, and Tennessee Williams.

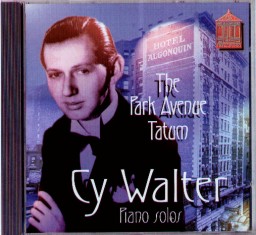

Walter recorded extensively from the Forties on, but until now none of his albums had ever been reissued, meaning that his name is virtually unknown today save to those lucky New Yorkers who once upon a time heard him live. Now Shellwood, an independent record label in England, has produced the first Cy Walter CD, a compilation of the pianist’s Liberty Music Shop 78s called The Park Avenue Tatum. All twenty-eight tracks are show tunes, among them “Begin the Beguine,” “Body and Soul,” “I Can’t Get Started,” “Liza,” “‘S Wonderful,” and medleys from such half-remembered Broadway shows as Jerome Kern’s Very Warm for May, Cole Porter’s Panama Hattie, and Richard Rodgers’ By Jupiter.

Walter recorded extensively from the Forties on, but until now none of his albums had ever been reissued, meaning that his name is virtually unknown today save to those lucky New Yorkers who once upon a time heard him live. Now Shellwood, an independent record label in England, has produced the first Cy Walter CD, a compilation of the pianist’s Liberty Music Shop 78s called The Park Avenue Tatum. All twenty-eight tracks are show tunes, among them “Begin the Beguine,” “Body and Soul,” “I Can’t Get Started,” “Liza,” “‘S Wonderful,” and medleys from such half-remembered Broadway shows as Jerome Kern’s Very Warm for May, Cole Porter’s Panama Hattie, and Richard Rodgers’ By Jupiter.

Except for the last two cuts, on which Walter is joined by Gil Bowers, all of the performances on The Park Avenue Tatum are unaccompanied piano solos, though the casual listener could be forgiven for suspecting that there might have been a second pianist lurking in the shadows of the studio. Peter Mintun’s superb liner notes reprint a 1940 thank-you note that Richard Rodgers sent to a friend who had given him a copy of one of Walter’s records:

Who are these fellows, Cy and Walter? For you’re certainly not going to stand there and tell me one man plays all that piano. I resent the whole experience, anyway. Here I’ve been yelling with pain at the way the “stylists” kick hell out of [my] original harmonies and you have to send me a record that stinks with style and still manages to leave all the harmonies intact. Further, I have never heard better taste. Why don’t you leave a man and his hates alone?

It’d be hard to describe Walter’s style more wittily, or exactly, than that. He plays a song the way the songwriter wrote it, embedding the tune in a richly textured accompaniment from which it shines forth like a well-lit, well-framed painting. Though his playing often recalls the similarly virtuosic style of Art Tatum, his good friend and favorite pianist, Walter rarely indulged in the iridescent substitute chords Tatum loved to pull out of his hat, nor does his playing swing the way Tatum’s did. He generally sticks to bouncy, danceable medium-brisk tempos, and his most staggering feats of technical prestidigitation, unlike Tatum’s, are tossed off with the unobtrusive discretion of a gentleman’s gentleman: you can listen and marvel if you like, or you can sip your drink and chat.

Such playing is typically appreciated more by musicians than critics, who are so put off by the imagined taint of commercialism that they too often throw out the baby with the bathwater. It didn’t surprise me, for instance, that Ethan Iverson, who plays piano with The Bad Plus, that quirkiest and least predictable of jazz bands, should have sent me an e-mail in response to the posting of last week in which I mentioned that Shellwood had offered to send me a review copy of The Park Avenue Tatum. “I have heard Cy Walter solo,” he wrote, “and it was amazing. You will be glad to get that one!” It figured that Iverson, who blithely disregards stylistic pigeonholes in his own bedazzlingly eclectic playing, would appreciate Walter. No, he wasn’t a jazzman, at least not in the ordinary meaning of the word–but who cares? As any number of wise musicians have been credited with saying, there are only two kinds of music, and Walter’s was the good kind.

Rogers Whitaker called cocktail piano “a minor art, but one of the more important ones.” I like that, and I like The Park Avenue Tatum enormously, not just because it’s so beautiful but because listening to it fills my mind’s eye with fetching pictures of a classier world, the same great good place that is chronicled in Intimate Nights, Rick McKay’s Broadway: The Golden Age, and The Complete New Yorker. My older friends, the ones who rail against rock and roll whenever you give them half a chance, are forever telling me how much nicer New York was in the Forties and Fifties. Me, I love it just as it is, especially when I saunter into the Algonquin Hotel’s Oak Room or stroll into a Broadway theater and plant myself on the aisle, notebook in hand. Every once in a while, though, I catch myself thinking, Yes, I have the greatest job in the world–but I still wish it was 1947 again. That’s how listening to Cy Walter makes me feel.

* * *

The Official Cy Walter Web Site is here.

Cy Walter plays “Body and Soul”: