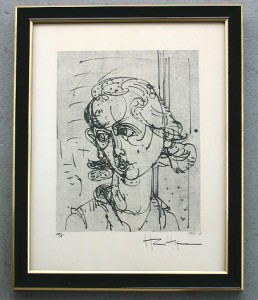

I mentioned the other day that I’d bought an etching by Hans Hofmann, the great abstract-expressionist painter and teacher whose work I love. What’s especially striking about this etching, at least from my point of view, is that it’s one of only three figurative works of art out of the two dozen pieces in the Teachout Museum, and the only one in which the subject’s face is fully visible. Milton Avery’s “March at a Table” is a portrait of March, the artist’s daughter, but her face is concealed, and in Pierre Bonnard’s “Femme assise dans sa bagnoire,” Marthe, the artist’s mistress, has turned her head away from the viewer. Since people who buy art normally buy what they like (unless they’re snobs or investment-oriented collectors), I always took it for granted that my unconscious avoidance of the human face said something significant about me. But I never did figure out what it was, and in any case my purchase of “Woman’s Head” presumably says something no less significant.

I mentioned the other day that I’d bought an etching by Hans Hofmann, the great abstract-expressionist painter and teacher whose work I love. What’s especially striking about this etching, at least from my point of view, is that it’s one of only three figurative works of art out of the two dozen pieces in the Teachout Museum, and the only one in which the subject’s face is fully visible. Milton Avery’s “March at a Table” is a portrait of March, the artist’s daughter, but her face is concealed, and in Pierre Bonnard’s “Femme assise dans sa bagnoire,” Marthe, the artist’s mistress, has turned her head away from the viewer. Since people who buy art normally buy what they like (unless they’re snobs or investment-oriented collectors), I always took it for granted that my unconscious avoidance of the human face said something significant about me. But I never did figure out what it was, and in any case my purchase of “Woman’s Head” presumably says something no less significant.

The woman in question, by the way, is a most interesting piece of work—pensive, not conventionally “beautiful” by any conventional definition of the word, and yet I can’t take my eyes off her. It’s been that way ever since I first saw her on line (I bought “Woman’s Head” from a Florida auction house). I couldn’t have told you why I found her so irresistibly fascinating, but I did, and do.

I reviewed a biography of Maria Callas four years ago for the New York Times. This is part of what I wrote:

Thelonious Monk, no stranger to paradox, once wrote a splintery, deliberately awkward jazz waltz to which he gave the title “Ugly Beauty.” He could have written it with Maria Callas in mind. A jolie laide with hard, bony features and a startlingly long nose, she contrived through sheer force of will to persuade audiences that she was a great beauty with an even greater voice. It was, of course, a con job. Her technique was full of holes, and the voice itself was more than a little bit peculiar-sounding, thick and foggy and apt to crash through the guardrails with no warning. The wobbly high C she sings in her 1955 recording of “O patria mia,” the big soprano aria from the third act of Aida, is one of the scariest moments in all of recorded opera—it sounds as if someone had grabbed her from behind and was shaking her like a cocktail.

The beauty of Callas’s voice was so strangely proportioned that some very discerning people simply cannot hear it…

No doubt some of my friends will be just as puzzled when they first see the ugly beauty who now makes her home in my living room. Nor will I try to persuade them that she’s pretty, because she isn’t. All I know is that I decided the moment I saw her that I couldn’t live without her. Love is like that.