Seeing Things: December 2011 Archives

Merce Cunningham Dance Company / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Brooklyn, NY / December 7-10, 2011

In addition to showing us wonders we'd never even dreamed of, Merce Cunningham (1919-2009), that inscrutable genius of modern dance, taught us a tough, valuable lesson: Dance is not forever. Its very evanescence increases its intensity at the moment of performance. It may register profoundly with the spectator but it inevitably disappears. Cunningham knew this and he made his plans.

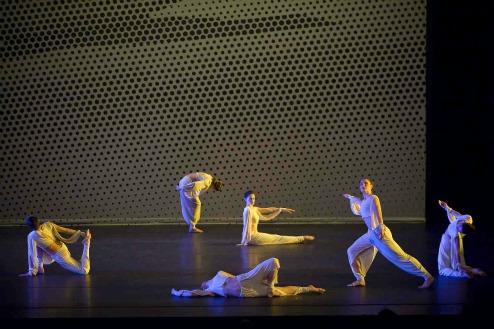

Members of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

According to the reports circulated after his death in 2009 (which are now, unsettlingly, being re-examined), the choreographer had decided that, once he was gone, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company would dissolve. The repertory that Cunningham had created for it was to be made available to other qualified companies, with a former Cunningham dancer sent to stage and coach it. The recipient company would also be given information in text and visual form to help make the production as "authentic" as possible. (This process has already been tried out with American Ballet Theatre's performances of Cunningham's Duets, staged by Patricia Lent, during its week-long season at City Center in November.)

Further, MCDC would begin a "long goodbye" by touring the world for two years. This is now all but accomplished. The penultimate performances of repertory--Roaratorio, Second Hand, BIPED, Pond Way, RainForest, and Split Sides--just took place at BAM. A week of shows in Paris follows. Still to come are six Events (Cunningham's familiar kaleidoscopic arrangements of excerpts from his dances) to be held in New York's Park Avenue Armory, December 29-31. Foreseeably the company's most ardent fans will be spending New Year's Eve cheering and weeping as they witness the end of something immensely important and the beginning of something unknown.

Meanwhile, some comments on the performances at BAM, where the spectators in the packed house focused laser-beam attention on a community of glorious dancers nurtured by a grand master. Come New Year's Day, most of them will be unemployed.

Roaratorio: Desjardins, Riener, Weber, Crossman

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The first of the programs given at BAM was devoted solely to Cunningham's hour-long Roaratorio, created in 1983. It was a perfect choice because of its ebullience, its sheer joy in the fertile--even crazy--mix of the casual happenings that constitute everyday, ordinary life. The full title of the John Cage score that plays in tandem with the choreography gives a "local habitation and a name" to the culture the dance evokes: "Roaratorio, An Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake." The reference, of course, is to James Joyce's unconventional epic novel, set in Dublin.

The Irish strain crops up continually in Cunningham's dance, most obviously in the airy, precise footwork that relates to Irelands' traditional step dancing and in the casual embraces of folk dancing, such as the Irish jig. The costumes, however, tell a different story. They're sleek, bright-hued rehearsal outfits, with three different colors allotted to each body. The performers add to and subtract from this get-up in the wings, which have been bared so we can see ostensibly off-stage activity simultaneously with the onstage performance. When they're officially onstage, a few dancers at a time spell themselves by perching on high stools, where they look like mid-20th century teens at the soda shop, eyeing their peers.

Throughout this long dance there isn't a moment when the steps and the incessantly shifting stage patterns aren't interesting. They may suggest this or that kind of situation to you or make you feel this or that, but these effects (or even their possibility) aren't essential. What counts is that the 14 moving bodies of the piece and their relationships to one another and to the space they're in seize your attention and refuse to let it go. Meanwhile, Cage is supplying the sounds of urban street life: infants wailing, dogs barking, chatter in various languages, the rumble of traffic, laughter. The entire affair is brimming with life.

A musical note: As is Cunningham's standard practice, Cage's score for Roaratorio was created independently of the choreography. The relationship of what we see and what we hear in a Cunningham production is that the two elements, created separately, share a chunk of time. In the case of Roaratorio, however, the music was not commissioned by Cunningham, as is usually this choreographer's practice, but created in 1979; Cunningham adopted it for his production. And, certainly, the two elements seem to be fused, not by the dancers' setting their moves to the score step for note, but in what looks like a celebration of the same matter in two different but miraculously compatible languages.

It's hard to resist reading a story--a terribly old-fashioned one--into the 1970 Second Hand. I didn't resist, just happily gave in to temptation. I took the piece to be about an aging artist who, having achieved marvelous things in his prime, is now looking at the person he has become and the role he has played in his relation to the rising generation. Admittedly, the theme I imagined is hopelessly corny, yet Cunningham's choreography is all subtle understatement.

Second Hand: (far left) Robert Swinston

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Second Hand opens with a remarkably long solo for Robert Swinston, in pale practice clothes. Swinston is, quite visibly, the company's senior member and has become a key figure in its administration. Here he's performing the role Cunningham choreographed for himself. He remains center stage, all but rooted in place, trying out minuscule moves that displace a part of his body just a few inches. In the solitude of the huge blank stage space, he seems to be examining the enormous differences such small distinctions make. Intermittently he tries out challenging balances that suspend him calmly between earth and air, that space being a dancer's true environment.

The light that falls on him brightens; a woman in rose enters, all springtime buoyancy. Swinston watches her from far upstage, as if not to disturb her lovely aura, and finally she comes to him. May and December, they run side by side, faster and faster, their path an oval loop, until she suddenly breaks away, leaving him alone.

Now a bevy of dancers floods the stage. Swinston keeps to the background, observing them intently. He might be their creator or director. Eventually he integrates himself, partially, into their dance. Finally he rests on the ground, half reclining, like an ancient Greek statue, admiring the moving figures and their ravishing arrested poses. Gradually--as if inevitably--the dancers pace off into the wings, leaving slowly, one by one. Alone once again, Swinston, the "Merce" figure, stands center stage, feet planted well apart, legs and chest stretched taut, arms lifted high. It's a pose of heroic triumph, but somehow without ego.

John Cage's score for this piece, which the composer archly called Cheap Imitation, came into being when he was refused permission to use Satie's Socrate for Cunningham's choreography. Inventively Cage kept the structure of the Satie, while altering its pitches through chance procedures.

BIPED

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The dance I enjoyed least on the BAM programs was BIPED (1999). Its title is the name of the motion-capture system that Cunningham used to choreograph once his own range of movement had been severely diminished by arthritis. Mind you, there was nothing to suggest the mechanical in the way the dancers moved, as one might have expected. What I found so off-putting was Cunningham's insistence on calling the wrong kind of attention to the tool that served him so well. He used it as decor, projecting BIPED's drawn moving images, as well as unrelated drivel that might have come from a Colorforms kit, onto a front scrim that remained obdurately in place throughout the piece. The scrim itself mildly obscured the live dancers behind it, diminishing their physicality and making them look far away.

Perhaps because these factors milked life from the dance, BIPED ran the risk of other Cunningham pieces that seem too repetitive and/or too long--it let your attention flag. Aaron Copp's lighting, which bronzes the dancers' flesh, is fine, and Suzanne Gallo's costumes are superb--variously cut unitards in fabric that lends its panoply of jewel tones a metallic glaze. I love the moment in which the dancers add gauzy grayish jackets to their outfits, making you think of brightly-hued butterflies setting time in retrograde by creeping back into chrysalis form.

The music was by Gavin Bryars.

Pond Way

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Like several important choreographers of the Pacific Northwest (Trisha Brown and Mark Morris come first to mind), Cunningham was acutely tuned to the workings of nature. His 1998 Pond Way, which opened the third and final repertory program at BAM, finds him turning toward the gentle and lyrical. Thirteen dancers clad in a white version of Arabian Nights garb move softly and lightly, their "landscape" an infinitely pleasing backdrop by Roy Lichtenstein that suggests rippling water through an ordering of black dots against a pale ground. Tucked, almost invisibly, into a corner, there's a rough sketch of one end of the crudest fishing boat imaginable (complete, however, with fisherman).

Gradually the dancers, whose footfalls make no sound, persuade the viewer that they're a flock of creatures--insects, fish, or birds seem most likely--whose little society retains its own communal life, all the while being embedded among a host of other groups sharing the same territory.

As it runs its course Pond Way offers many an opportunity to observe tactics that Cunningham invented or co-opted for his choreography. For one example: Five women do a particular phrase in unison, but each displays herself to the viewer at a different angle so that the phrase looks different on each, while remaining, strictly speaking, the same. For another: A group of dancers working together suddenly divides its function into two complementary parts. Some of the dancers, still moving busily but now rooted in place, become a maze; the remaining dancers become Theseus-clones, threading their way through it.

Finally a group exits, one dancer after another, performing a striking version of classical ballet's grand jeté (the leap adds a minute but brilliant flash of motion when it reaches its height). When the last leaper goes, the dance is over, as a school of fish or flock of birds vanishes if something disturbs the element in which it swims or flies. That finish seems abrupt if you love this dance, because you wish (expect, even) that it could go on forever as do the processes of nature.

Brian Eno's score for Pond Way is peaceful yet haunting. It suggests the cries of animals, howling winds muted by being distant, gongs echoing through endless corridors.

RainForest: (standing) Brandon Collwes and Silas Riener; (prone) Krista Nelson

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The 1968 RainForest offered a diametrically opposite view of nature--a tooth, claw, and sex version. Andy Warhol's stunning decor is, in a way, a distraction from what's going on among the proto-humans onstage. It consists of a flock of gleaming Mylar pillows, inflated to the bursting point. Some hang from above on all but invisible threads. Others loll on the stage floor (at times, spookily, just inches from it), moving lazily or in instant retreat as the cast of six makes arbitrary contact with them. The dancers wear skin-toned, roughed-up body stockings; Warhol had wanted them nude.

An initial couple seems to represent lovers-in-innocence until the twosome is disturbed by a violent man whom the woman takes quite a shine to. After that intrusion one figure replaces another in La Ronde fashion and the sexual activity becomes a sensuous account of unquenchable lust, trailing brutality in its wake. Memorable images include a pairing in which a man drags himself painfully across the floor on his belly with a spent woman laid out on top of him; they seem to be made of one flesh. Another is the appearance of a woman who's an iconic Lilith, her thick dark hair whipping around her face like a curtain of evil. She's swift, avid, and utterly reckless.

The animal cries that emanate from David Tudor's score reinforce the feral behavior of the people. The soundscape also includes birdsong, whistles, drumming, and other forms of percussion.

Obviously, this stunning piece is open to many another interpretation. No matter what one's reading of it is, it remains a forceful argument against the notion that all Cunningham's works are the same.

Split Sides: Silas Riener

Photo: Stephanie Berger

As a preface to Split Sides, the final work in the BAM series--presumably the last New York would see of Cunningham's repertory as performed by his own company--David Vaughan, the troupe's archivist, presided over a passel of VIPs' casting of a die. The results would determine the order of the two versions that had been created for each of the elements in the production--choreography, music (one score from Radiohead, the other from Sigur Rós), costumes, decor, lighting. Making this invitation-to-chance a public stunt instead of a privately used creative tool struck me as a lapse of taste uncommon on Planet Merce.

From its premiere in 2003, I thought Split Sides a lamentable effort to make Cunningham appear "with it," when this choreographer had been Mr. With It himself from the start of his career. Only Vaughan could have made the public die-casting palatable. Not only a distinguished dance writer but also a dapper veteran performer, Vaughan was witty and utterly compelling. I'm not going to comment further on Split Sides; what I wrote about it just after its premiere is what I still think. Except that, this time, Silas Riener aced a solo--reworked for his particular gifts--that had the audience gasping in amazement.

Amazingly, when the curtain fell on the company for what was ostensibly the last time it would be performing the Cunningham repertory in New York, its home town, nothing special happened. Was this an example of elegant stoicism? The curtain calls were pretty much the same as they had been throughout the four-day run. The dancers stood shoulder to shoulder in a single horizontal line and bowed. None of them was singled out as being more important than the others. A good part of the audience stood to applaud enthusiastically. There was perhaps one extra call this time, maybe two. No flowers were presented onstage or thrown from the audience. One dancer kept gesturing toward the musicians in the pit. Then the curtain fell for good and that was it. At least for now.

The performers for the BAM engagement were: Brandon Collwes, Dylan Crossman, Emma Desjardins, Jennifer Goggans, John Hinrichs, Daniel Madoff, Rashaun Mitchell, Marcie Munnerlyn, Krista Nelson, Silas Riener, Jamie Scott, Robert Swinston, Melissa Toogood, and Andrea Weber. They are remarkable in themselves and even more so as a collective.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Angel Reapers, by Martha Clarke and Alfred Uhry / Joyce Theater, NYC / November 29 - December 11, 2011

The oddest thing about Martha Clarke and Alfred Uhry's Angel Reapers is that it has no plot. This despite the fact that Uhry is a widely respected American playwright, as his Pulitzer, Oscar, and Tony awards attest. Clarke herself, a founding member of the tremendously popular Pilobolus, is widely known for haunting dance-theater pieces, in which her vivid imagination and penchant for the perverse reveal the world's underside. A MacArthur Fellowship (the "genius grant") tops her long list of awards. How could she not have noticed that the 75-minute work she and Uhry had concocted about that unique American religious sect, the Shakers, desperately needed the architecture and propulsion of a story? As matters stand, Angel Reapers plays like a documentary, though it's not at all clear how much of its content is fact and how much fiction. What's worse, it doesn't seem to have any point.

The Dark Is Light Enough: A scene from Martha Clarke and Alfred Uhry's Angel Reapers

Photo: Rob Strong

Two things commonly known about the Shakers: One: They were committed to the rule of celibacy. Two: Along with spoken testimony to their rigorous principles (at its most ecstatic, speaking in tongues) and confession of their infringements, their rites included movement: stepping, stomping, and shaking that mounted in intensity in order to exorcise their sins. The violence of this "dancing" was like that of spiritual possession, its climax occasionally ending in a faint. (A third fact generally known about the Shakers is that they constructed home furnishings breathtaking in their purity of form, but let that pass, since Clarke and Uhry didn't find it pertinent.)

Here's what the creators of Angel Reapers did give us. A cast of six women and five men who can, to varying degrees, dance, sing, and move eloquently. The movement element is well covered by having the best dancers doing the challenging parts such as falling heavily to the floor and writhing vigorously in the throes of religious, or plain human, passion. The a cappella singing of authentic Shaker work songs and hymns sounds quite natural and blessedly avoids theatricality. It goes without saying that "Tis a Gift to Be Simple" is represented; Aaron Copland eked out a whole ballet for Martha Graham--Appalachian Spring--from it. The spoken word doesn't fare so well; the performers with insufficient training in diction and projection are not convincing. Strangely enough, none of the people on stage seems fully "real"-- either as a character identified in the program (Sister Susannah Farrington, an abused wife; Brother Moses, a runaway slave) or as a fully confident performing artist, so it's hard to empathize with them. We're not drawn into their world; we just watch them from afar.

Angel Unaware? Asli Bulbul in Angel Reapers

Photo: Rob Strong

We first see the full cast at its communal worship, making clear what dictates they've vowed to obey. Gradually we learn how each member became part of the community. (This material has more than a hint of AA meetings behind it.) Eventually we come to various members' breaking the sect's stringent rules, for the most part the one about chastity. The issue is, of course, the tension between the Shakers' will--which could prevail only in a community giving itself over to group hysteria--and human reality. Inevitably a man and a woman touch--merely touch--and the whole house of cards collapses. Intercourse has its day, heterosexual first, then, Clarke being an equal-opportunity artist, same-sex (a gorgeous duet, featuring lifts that are also embraces, represents a pair of men coupling). Last, a radiantly pregnant woman and her partner leave the fold. Mother Ann Lee, historically the woman who brought the sect to America, gets worried. Very worried. And, ambivalent. An uncompromising leader, she only wanted to teach her chosen people how to live in order to be sure of Heaven when they died. Now she's beginning to feel some very human sympathy for the transgressors.

The end of the piece remains an enigma to me. Left alone, the despairing Mother Ann has a flesh-and-bone vision of four men who are buck naked, though never in full-frontal view of the audience. (Granted, this modesty may have something to do with local laws.) One member of the quartet, William, who is Ann's brother, points out, "My soul is an angel. My body is a man. They are at war--man and angel. The angel is pure. The man is strong. I fight him. I never win. Why is it so hard?" When he leaves, Ann is alone again, sitting in one of the sect's unforgiving straight-backed chairs. We see her in profile, as if in effigy, and hear her singing, faintly but clearly, as if to sustain her own faith, while the light fades to dark.

Go to see this venture if you like, but keep in mind the fact that Doris Humphrey, a key choreographer of mid-20th-century modern dance, did the subject shorter and better. The Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, at Lincoln Center, will show you The Shakers, made by Humphrey in 1931, on film--for free.

The performers in Angel Reapers are Sophie Bortolussi, Asli Bulbul, Patrick Corbin, Lindsey Dietz Marchant, Birgit Huppuch, Gabrielle Malone, Peter Musante, Luke Murphy, Andrew Robinson, Whitney V. Hunter, and Isadora Wolfe.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary