Seeing Things: November 2011 Archives

New York City Ballet: The Nutcracker / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / November 25 - December 31, 2010

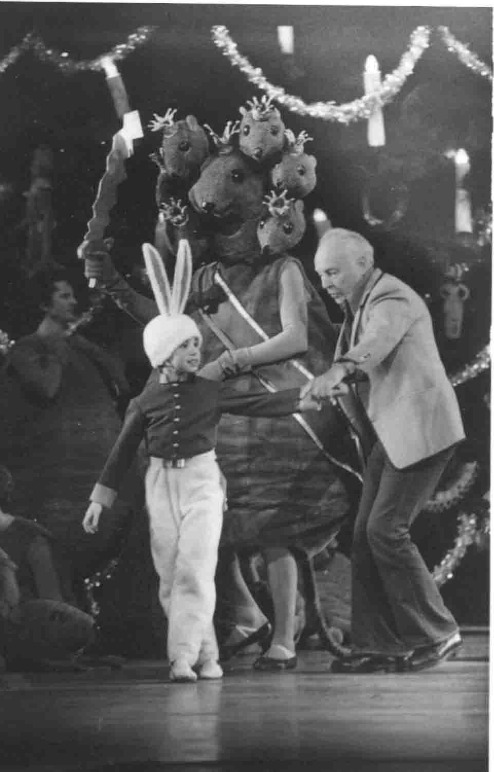

God Is in the Details: George Balanchine, creator of the New York City Ballet's The Nutcracker, coaching the smallest of the toy soldiers at a dress rehearsal

Courtesy of the New York City Ballet archives

With its premiere in 1954, George Balanchine's version of The Nutcracker, choreographed for the New York City Ballet and set, of course, to Tchaikovsky's eloquent score, inaugurated a craze for the Christmastide ballet that promises never to abate. This season City Ballet itself is adding to its annual "Nuts" season (running through December 31) with a live telecast of the ballet on December 13, which will be on view in more than 500 movie theaters cross-country. On December 14, PBS's Live From Lincoln Center will present the ballet.

All this broadening of the audience for the production is surely admirable. Comparatively few people have easy geographic access to the live version that fills the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center; even fewer have easy financial access to it. Privileged though I am, being a New York-based dance critic, I dare to say that live is best and, moreover, that the Balanchine Nutcracker remains more splendid than all the subsequent renditions I've seen.

I attended this year's opening night performance on November 25. Overall it was lavishly rewarding. Knowing the production so long and so well--and having written about it so often--I gave myself the freedom to report this time simply on the elements that particularly caught my fancy.

Getting to Know You: Fiona Brennan as Marie, clutching her precious nutcracker as she learns how it works

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The Nutcracker boasts a horde of characters, most of them unforgettable. Not all of them are human. The first creature we encounter is a pink-gowned angel with sweeping wings--oversized ones that appeared intermittently in Balanchine's ballets down the decades, indicating this choreographer's belief in the power of otherworldly forces. Hovering over the snowy roofs of a modest town and stretching her arms out to a shooting star, the angel dominates the front cloth we gaze at as the orchestra plays the ballet's overture.

Next we meet a family that lives in the town, the prepubescent Marie, the elder child of Dr. and Frau Stahlbaum, and her irrepressible kid brother, who are celebrating Christmas Eve according to the customs of Germany's upper middle class in the late 19th century. Given the casting I saw, it was Marie, the child heroine of the tale, who interested me most. Played by Fiona Brennan, Marie is innocent, unselfconscious, and open to what the world has to offer her. So far, it would seem, the world has not let her down.

Brennan is plain-looking (in the way that Mary of The Secret Garden is plain) and miraculously unaffected. As the events of the ballet's first act spin out, evolving from the domestic to the hallucinatory and the ecstatic, she looks as if she's participating in real-life happenings, real feelings. Her Marie is a child without guile who experiences everything--even the visionary turns the plot takes--as if it were true.

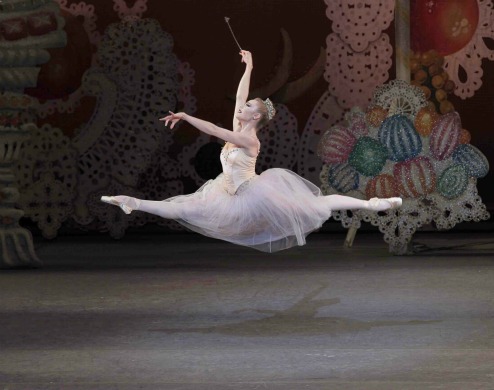

Let Joy Be Unconfined: Sara Mearns as the Sugarplum Fairy

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Sara Mearns was the evening's Sugarplum Fairy, a fact that would make any balletomane or newbie to dancing feel blessed. (Mearns is a dancer whose magnificence is evident at first sight, because of the grace and visceral power of her lush body.) We see her first in Act II, appearing amongst a group of angel-children who've been skimming over the stage in geometrical patterns. Once she appears in their midst they make a wide circle around her, like acolytes uniting with their leader. When Marie and the Nutcracker Prince arrive on the scene, she asks them, genuinely wanting to know, "How did you come to be here?" She seems fascinated by the boy's detailed mime account of the events that drew them to her kingdom--one of the ballet's tours de force--and deeply grateful for the explanation. In both these passages she behaves like an ideal mother, understanding aunt, or gifted schoolteacher of the young--exuding love and concern for the child or children in her midst.

Towards the end of the ballet, in the grand pas de deux with a cavalier who appears from nowhere--with no narrative identity, but simply to support the ballerina in the duet's tricky partnering--Mearns continued to defy any impulse a viewer still might have to read her as flat, two dimensional. Alone or with a partner, she invariably works in three dimensions, a moving sculpture with a very human heart.

Admittedly, she didn't treat Jonathan Stafford--on duty for the occasion--as an emotional foil. How could she? She'd never met him. Suzanne Farrell, another remarkable Sugarplum, handled the problem of the undocumented cavalier just by being grander and more mysterious than her partner, who is needed but not recognized. Mearns, for whom remoteness is not a familiar mood, couldn't relate to her escort the way she had to the flock of small angels, but was simply magnificent on her own, as if he were invisible (which he was, almost), nailing her every move in the pas de deux, and triumphing in her solos.

Nature's Charms: Tiler Peck as Dewdrop in the garden of the waltzing Flowers

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Second only to the Sugarplum Fairy role in The Nutcracker is the brief but dazzling part of Dewdrop, leaping and whirling her way, all clarity and speed, through the mazes formed by a bevy of lyrically waltzing Flowers. I saw Tiler Peck, whose performance was a technical marvel, as it is in any role she tackles. Peck was already an astonishing dancer--and a remarkably beautiful woman--when she joined City Ballet and she matured swiftly on the job, becoming more subtle and sculptural without losing a jot of her panache. I can't think of any woman now in the company who could equal her as Dewdrop. And yet, much as Peck is almost all you might wish in the part, she still lacks the driving fervor that Heather Watts and Karin von Aroldingen, with much less claim to the title of "ballerina," projected years back--a kind of ecstatic madness, driven by some sort of life force.

There's also an invisible being present--a soul that suffuses this production: Balanchine's, especially Georgi Balanchivadze's. As a young student in the renowned dance academy of St. Petersburg's Mariinsky Ballet (Pavlova's school, Nijinsky's, Nureyev's, Baryshnikov's), Balanchine played the Nutcracker Prince. Decades later, creating his own production for the New York City Ballet, he co-opted from the Russian version the mime monologue with which the young Prince explains to the Sugarplum Fairy the dramatic events that led to his arrival with Marie in the Land of Sweets. During his lifetime, as one Prince succeeded another, Balanchine personally coached any boy new to the role. (Two casts alternate in the children's roles, and the youngsters must abandon parts for which they've outgrown the costumes.) Now that Balanchine is gone, the children's ballet mistress, Garielle Whittle, often tells her charges in rehearsal, "Mr. Balanchine used to say . . ."

Each time you see Balanchine's Nutcracker, certain passages in it seize your attention, not just for their choreographic deftness--with Balanchine you've learned to take this for granted--but for their emotional resonance. Think of the moment in the Party Scene, for instance, when the fathers dance with their little daughters, becoming the girls' first cavaliers as they're introduced to the pleasures and strictures of social life. I could name many more, as could all frequent viewers, but will cite just one: Who with any heart could resist the sight of the two children, Marie and her Prince, hand in hand, backs turned towards the audience, walking trustfully toward a faraway star in a darkening snow-covered forest?

When the final curtain fell on these wonders and the audience stumbled out of the theater into reality, I felt--once again, but even more intensely--that The Nutcracker, as conceived by Balanchine, is among the most refreshing and civilized of entertainments.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

American Ballet Theatre / City Center, NYC / November 8-13, 2011

This season's gala-event costumes for women of a certain income emphasize cascading ruffles in weak-willed pastels or glowing jewel tones. The men continue to sport black-tie mufti with almost no rakish variation on the theme. Expense is evident, as is the eternal question of hoi polloi concerning the gowns with obviously crushable skirts, How does she sit down in it?

Despite the War: American Ballet Theatre's Luciana Paris in Paul Taylor's Company B

Photo: Gene Schiavone

This fashion report comes from the opening night of American Ballet Theatre's week-long fall season at the handsomely renovated City Center--now gorgeous and comfortable beyond belief. The repertory for the week eschewed the company's multi-act classics (Swan Lake, now in warped form, Giselle, et al.) and wannabe classics (Neumeier's Lady of the Camellias, Kudelka's Cinderella) that ABT offers in its long spring seasons at the Metropolitan Opera House. Each program in the City Center run purveyed three or four ballets that owe more to modern dance (Paul Taylor's), postmodern dance (Merce Cunningham's, Twyla Tharp's), and ballet being catapulted into the future (Alexei Ratmansky's), than to the strict conventions of classical ballet.

Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: Kristi Boone in Twyla Tharp's In the Upper Room

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

The high point of the opening night show was, incontestably, Twyla Tharp's In The Upper Room. Created in 1986 for Tharp's own company and set on ABT in 1988 the ballet is a powerhouse; it starts at the top of the scale energy-wise and escalates from there. Philip Glass's driving score is a full partner in the dancers' trip to Paradise, assuming that's what the "upper room" indicates.

Upper Room divides its cast into two different sects: those shod in sneakers (affectionately called the Stompers) and those who favor classical dance footgear, which means pointe shoes for the ladies. The two camps eventually merge, as they have in the course of Tharp's career.

Tharp's relentless choreography displays dozens of terrific things you can do when you mate academic dancing with Tharp's personal style, a brew of both classical and modern dance, jazz, pedestrian gesture, and myriad other fascinating ways of moving that she fixed on in her childhood from an eclectic set of lessons and since then through her magpie instinct. Boxing, just for starters.

Upper Room is perfect proof of the fact that Tharp is a demon of patterning. You can feel her brain ticking away as one design succeeds another. Her choreography offers a kaleidoscope of moving bodies arranged in space, each image utterly clear and then gone, giving way to the next, just seconds after you've taken in the preceding one.

The overall pace of the dance seems furious, the action mounting in fervor. The speed makes obvious the risks the dancers are often taking--seemingly without fear but, rather, savoring the reward of attempting the near-impossible and achieving it. It's quite possible that in this piece Tharp is telling us this is one of the main factors that make a dancer dance.

Costumes and lighting are not relegated to supporting roles in this production; they're striking essentials. Norma Kamali designed a wardrobe of prison-striped black and white pajama-like outfits, accented by a blinding red. (The women's gleaming red pointe shoes (worn over red socks) is a terrific latter-day sequel to the demonic footgear Moira Shearer wore in the best dance film ever made.) As the dance progresses, the cast gradually sheds the coveralls to reveal more and more carmine underneath.

The lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton astonished the audience when Upper Room was first performed. She filled the upstage area with a drifting fog from which the dancers emerged--as if by magic--and into which they disappeared. At the City Center performances, which Tipton did not supervise, the entire stage was suffused with smoke that never moved and functioned as a pale gray scrim that never lifted, thus diminishing some of the action.

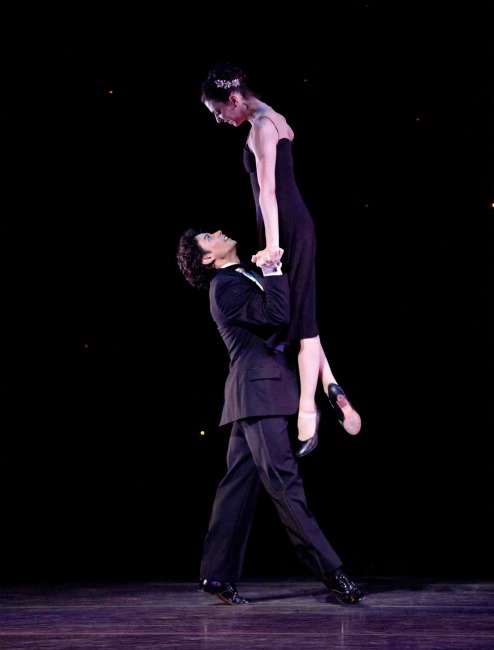

Starry Night: Herman Cornejo and Paris in Tharp's Sinatra Suite

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

Herman Cornejo's return to performing after a long recuperation from injury was reason enough to be happy and excited by the evening's performance of Tharp's Sinatra Suite. Cornejo is a unique dancer--an extraordinary technician who, refusing to be typed by his scrappy-kid-brother looks, has extended his abilities to danseur noble roles, modern dance roles, you name it. At his best he's an artist who infuses everything he does with life.

Cornejo wasn't at his best in this duet on opening night, He was having obvious trouble with the lifts, and his partner, Luciana Paris, was of no help to him, apparently having problems of her own. He also tended to separate elements in the dancing that should be fused. He called undue attention to feats demanding classical ballet prowess because he executed them so immaculately, meanwhile failing to articulate the jazzy, gymnastic, and casual elements that are essential to Tharp's signature style.

He was encouragingly better in the closing number, a solo to "One for My Baby (and One More for the Road)." There, the lyrics conjure up a guy who has been through it all telling his sad story to the bartender in a seedy dive about to close for the night. Here, too, Cornejo danced with too much emphasis on the classical bits and too much self-conscious acting, but also with hints that he was beginning to set matters right. The important thing is that he's back on stage. He's not just one of ABT's great stars; he's indispensable.

Sinatra Suite got its ideal cast at a later performance when Paloma Herrera and Marcelo Gomes took the leading roles--they're both innately sexy dancers and have reciprocally crackerjack timing. The richness they brought to the succession of songs that runs from dewy-eyed romance to the inevitable break-up went so far as to hint toward the end that it's the woman, not the man, claiming "I did it my way." Being a generous performer as well as a singular one, Gomes let Herrera go for it.

As for the choreography, not only is it inventive, it's also vibrantly expressive about the shifting moods of love. (In the Upper Room has only one mood: driving on Ecstasy.) To my mind, though, the ballet was even better in its original incarnation, the 1982 Nine Sinatra Songs--more thrilling, more sensuous, occasionally even amusing (remember the bumbling young sweethearts of "Somethin' Stupid"?). Using more songs, that piece involved several couples and was originally danced by the singular members of Tharp's own company, back in simpler times, when the choreographer had her own company.

Five in a Row: A line-up of ABT's male dancers in Demis Volpi's Private Light

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

The big curiosity of the evening was the premiere of Private Light by Demis Volpi, who is a mere 25 years old. The Argentinean-born dancer-choreographer trained in his homeland, then in Canada, and finally came under the wing of the Stuttgart Ballet, joining the company in 2004. He began to choreograph in 2006 and has enjoyed the support of Stuttgart's Noverre Society, which has aided several emerging choreographers who went on to international fame. He has since gathered much attention and much praise, but I can't join in the applause.

Generous apologists for Volpi are bound to say: He is a beginner and he will learn. But anyone examining the careers of the western world's choreographic geniuses (Balanchine, Graham, Ashton, and Tudor leap to mind) will see that they refined their craft over the years--choosing, according to their own inclinations, whose inventions to imitate, steal from, or build upon--but that their artistry and unique imagination were unmistakably in them from the beginning.

Clearly, Volpi has learned the set rules of his trade. For example: Select a movement theme, state it early on, then thread it throughout the piece, giving it a few exact repeats but even more variations. The trouble with Volpi is that he hasn't absorbed such rules organically; they remain merely intellectual propositions that never become visceral or vivid--or make any obvious point.

In Private Light Volpi fixates on the idea of the line-up, the kind in

which the police present a prospective witness for the prosecution with a handful of people (among them the suspected criminal) who resemble one another. They stand under bright light, their bodies evenly spaced in a horizontal line. The Volpi version uses five male-female couples and insists, throughout the piece, on the rule of five, a tactic that makes the ballet feel increasingly tedious and contrived.

A major feature of the piece is The Endless Kiss--heavy mouth-to-mouth smooching. Its repetition is neither interesting nor (as I assume the choreographer meant it to be) funny. Another big deal has one of the men (Joseph Gorak) neatly executing excerpts from a ballet barre without a barre to support him, as a little horde of his colleagues are periodically revealed to be watching him. The solo is a feat, to be sure, but a dry one, and the point of it remains murky.

The central segment of Private Light is a duet for Simone Messmer (who creates a different persona for every one of her ABT roles) and Cory Stearns. Messmer first appears alone, doing one capricious thing after another, like a girlchild who's been brought up under the free-to-be system. When her partner arrives--signaling the beginning of her adulthood--her shenanigans become grotesque enough for the spectator to wonder if she's being abused. She keeps collapsing, a victim in his arms. Am I just imaging this or is Europe's contemporary ballet more tolerant of nasty behavior towards women than we are in America?

The most agreeable element of Private Light was its accompaniment--selections ranging from folk-style music to classical pieces by Albéniz and Villa-Lobos, enticingly played at the edge of the stage by guitarist Christian Smith.

Ménage à Trois: Alexei Agoudine, Xiomara Reyes, and Grant DeLong in The Garden of Villandry, co-choreographed by Martha Clarke, Robby Barnett, and Felix Blaska

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Set to Schubert's beguiling Trio No. 1 in B Flat, The Garden of Villandry, co-choreographed by Martha Clarke, Robby Barnett, and Felix Blaska, had its world premiere with the adventurous Crowsnest group in 1979 and its company premiere with ABT in 1988. It's one of those bagatelles that lasts a surprisingly long time.

Villandry, as the program might usefully have mentioned, is one of the16th-century châteaux on the Loire (small castles, such as fairy tales depict), best known for its elaborate formal gardens. The site, painstakingly refurbished and scrupulously tended, is open to tourists whose reaction, in their myriad tongues, is invariably "lovely" or "amazing."

With the musicians in an upstage corner, a trio in Edwardian dress dances the subtle--and mercurial--relationships among two gentlemen and the lady they both desire. The dancers on this occasion were the perennially lovely Julie Kent; Roman Zhurbin, a sturdily built and quietly resourceful character dancer; and Julio Bragado-Young, who looks like a stock character--the pale, undernourished young tutor of yore who has a few wealthy children under his care and a head full of impossible dreams.

The dancing is a detailed study of the myriad ways in which three bodies can join and intertwine and (very rarely, never creating too much distance between them) separate. Hands touch and withdraw. Gentle kisses, mostly a brush of the lips on a cheek, are given and accepted. Secrets are whispered behind a cupped hand held to the sharer's ear. The lady lets her head fall on one suitor's shoulder and then, playing fair, on the other's. She is swung into the air by both, her long white skirt flying with her--a shroud of chastity, perhaps. She rejoices in the admiration her courtiers give her and sweetly, always tactfully, returns the pleasure.

Imagine, if you're a member of the so-called gentler sex, the most romantic and refined of your female friends actually admitting she wanted to live such a life. "Oh," you might well scoff, "it's like a perfume ad." But then who are you to judge? You don't wear perfume.

As the ballet went on, I expected some crisis to the situation that had been so artfully and meticulously presented, some climactic scene, some horror, perhaps, or at least some melodrama. (Throughout a long and fruitful career, Clarke has regularly revealed her penchant for eerie, alarming scenarios.) Even when I decided that the participants in the trio probably don't crave a solution to their problem, that they no doubt find it exquisitely romantic, I still remained ignorant of the tone the piece was taking toward the whole business. One contextualizing clue: the ballet begins and closes with the three dancers staring reproachfully at the audience as if we lookers-on were voyeurs.

Ménages à Deux: Paloma Herrera and Eric Tamm in Merce Cunningham's Duets

Photo: Gene Schiavone

ABT's acquisition of Merce Cunningham's 1980 Duets, one of the late choreographer's most accessible works, may be a forecast of how that repertory will fare when the Cunningham company disbands at the end of this year, as part of Cunningham's plans for his works' life after his own death. His dances will be released to other qualified troupes, with a former Cunningham performer appointed to set and coach the work.

I can't imagine Cunningham's dances being in better hands than those of Patricia Lent, who transmitted Duets to a pair of ABT casts. In a particularly rewarding Works & Process program at the Guggenheim Museum in October, Lent worked with Isabella Boylston and Craig Salstein, making sparse, concise corrections and suggestions in the most even voice imaginable, never inflecting the information with her personality. She might have been a latter-day guru. Everything she said made good sound sense.

In performance the plainspoken yet mysterious choreography suggested a realm of dancing almost alien to ABT's nonetheless eclectic repertory. It was only natural that many of classical ballet's conventions, deliberately abandoned by Cunningham, automatically surfaced: dancing to the audience; dancing that ended in freeze-frame images; dancing that emphasized the brilliance of a certain step or phrase. But most of the performers seemed to respect the unfamiliar horizons and want to explore them, which is a good sign.

Fighting Depression: A scene from ABT's production of Paul Taylor's Black Tuesday

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Paul Taylor's dances have been well absorbed by ABT's dancers, as was evident in the week's performances of the 1991 Company B and Black Tuesday, created in 2001. In a method Taylor has worked out for himself, both pieces were first done by classical companies and then quickly absorbed back into the Taylor company's repertoire, where they seemed to find their most genuine interpretations. Still, Taylor has long claimed that he has no problem with having his choreography performed with a classical accent. Moreover, ABT's version of the pieces I've named have, a decade or two after they were choreographed, taken on an ebullient life. The reason? Increasing familiarity with the Taylor way of moving and the ability of the upcoming generation of classical dancers to excel in a wide range of styles.

Ballet Blanc: Reyes and Cornejo in Alexei Ratmansky's Seven Sonatas

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

Alexei Ratmansky's 2009 Seven Sonatas, set to seven of Scarlatti's Keyboard Sonatas (played onstage by Barbara Bilach), is a delectable choreographic feast. I thought it marvelous when I first saw it, but it's even more gratifying now, having grown richer through repeated performance--and through my own better appreciation of it after repeated viewings.

As usual, Ratmansky is rigorous here, offering a cornucopia of invention without leaving the context in which he's working. And as usual his choreography is packed with evidence that he has learned from the masters he honors. He even pays them overt homage; I spotted brief quotes from Fokine, Bournonville, and Balanchine, among others. And of course there are little jokes--amusements, rather--along the way, which seem to reveal the sheer pleasure that dance gives him.

Three couples constitute the cast of Seven Sonatas, so it might be called a chamber ballet. It might also be termed a ballet blanc because it's costumed in white--for the men as well as the women, actually--and because it refers to the Romantic vein of purity and fleet, weightless execution. It also seems to be plotless, but Ratmansky is an irrepressible creator of subtexts. At one of the two performances of the piece that I saw in ABT's crammed week at City Center, I was convinced that the ballet was revising the story of Bournonville's La Sylphide: Young man captures the otherworldly sylphide and--guess what?--they proceed to live a charmed life, full of laughter. Ratmansky danced and choreographed for the Royal Danish Ballet for several years, so he must know the Bournonville version by heart.

ABT's week at City Center was a terrific stylistic challenge to its dancers, a showcase for performers exiled to lesser roles in the blockbuster multi-act works that prevail in the company's long spring season at the Met, and a way to attract an audience that isn't mired in old conventions. Is it possible that the company's two profiles can be reconciled? If that seems impractical, how about two weeks at City Center next year?

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Duŝan Týnek Dance Theatre / Tribeca PAC, NYC / October 27-29; November 3-5, 2011

Duŝan Týnek Dance Theatre

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Seeing the Dušan Týnek Dance Theatre, recently at Tribeca PAC, in the second of the two programs it offered, made me wonder why the standing of its marvelous choreographer hasn't graduated from "promising" to top-of-the-line. If he were working for a big institutionalized company like ABT or New York City Ballet, he might blow contenders like Brian Reeder and even Benjamin Millepied off the map.

Czechoslovakian-born, Týnek emigrated to train and dance in New York. His mentors include Aileen Pasloff, Merce Cunningham, and Lucinda Childs. He formed his own company, Dušan Týnek Dance Theatre, in 2002. From my first sight of his work, I was hooked on what he was doing.

"Ambitious beyond its power to deliver, the piece is filled with vision, charm, and wit," I wrote about his Pilot's Dream, and "preserves uncorrupted the poetic fantasies of childhood." This was in the Village Voice, back in 2003. The following year, again in the Voice, I called his Pink Tree, a duet for women, "astutely constructed and beautifully danced" and noted Týnek's "skill at implying feelings through movement."

Since then, many a dance writer has noted his gifts: imagination and originality, first of all; then, a seemingly inborn command of structure; an uncanny ability to make movement express emotion and atmosphere; and a dance vocabulary that bonds classical and modern techniques in a way that seems natural, not studied or just plain awkward.

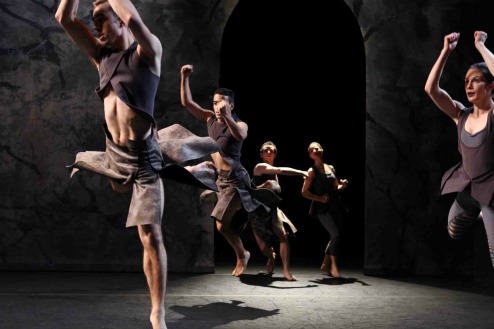

Duŝan Týnek's Portals

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The cast for Portals was: Alexandra Berger, Ann Chiaverini, John Eirich. Emily Gayeski, Elisa Osborne, Samuel Swanton, Satoshi Takao, and Nicholas Wagner.

Two dances on the three-work program, Portals and Widow's Walk, were new this season. Both demonstrate Týnek's steadily increasing sophistication. Portals, was the most powerful piece I've seen from him yet. All eight of the company's dancers are dressed in Karen Young's boldly cut leather-look costumes, which bring to mind warriors of ancient Greece or Rome. Both men and women move with gutsy force--and considerable sensuousness--before and behind Mary L. Hamrick's pale translucent drop cloth. The drop is patterned with jagged gashes indicating cracks (from age or from assault), and punctuated with a huge cutout in the shape of an upside-down U. Hence the portals of the title.

Týnek's choreography conjures up a tight community (one passage is even influenced by central European folk dancing), with a lust for life, equally feisty in war and mating, actually not separating the two. The full-blooded thrashing action alternates with contemplative moments in which the participants seem to reflect on who they are and, as Yeats put it, what is past, or passing, or to come.

Týnek's Portals

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

A master of understanding the relationship of dancers to the space in which they move, Týnek makes the most of the different planes of action created by the drop cloth, activating each of them at the same time, but in contrasting ways. For instance, a brief intense duet--a couple making a significant personal connection--occurs in front of this scrim while, behind it, figures in silhouette pace back and forth in a horizontal line, a restless, anonymous parade. Adding yet another vibrant element to the piece, the music, by the post-modern composer Aleksandra Vrebalov, was played live and onstage by the equally daring string quartet ETHEL.

Widow's Walk refers to the porch-in-the-air that once surrounded many a coastal New England home. Up high, so it provided a view of the waters from which fishermen drew their living, it was cantilevered against the building and reached all around it. The fishermen's anxious wives paced it, watching for their husbands to return, fearing that, as often happened, they might be seized by the turbulent waves.

Týnek's Widow's Walk

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

We meet the wives, then the men. The couples, four of them, rejoice in their mates, but once the men leave, the women revert to their apprehensive stalking. We see the men again, stepping straight towards us, making spasmodic gestures that indicate hard physical labor. Then the women return, now in white tunics and white bathing caps; they have become the sea itself--unpredictable waves with their ironically beautiful lacy edging of foam. Gentle at first, the waves escalate to sheer rapaciousness, as they devour and destroy their prey. The men put up a vigorous fight, but there's no victory to be had over the mindless forces of nature. The piece ends with the four human couples whipping through the space as if their rage at death will never end. When the men vanish for good they take with them even the comfort that pacing the widow's walk brought to their wives. What the women feared has come to pass, leaving nothingness.

Widow's Walk, set to music by Mary Rowell and Phil Kline, was also accompanied, live, by ETHEL.

Týnek's Transparent Walls

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The evening's opener, Transparent Walls, set to a score by Vrebalov, a Týnek favorite, presents a dove-like couple who are all in all to each other against a crowd of six who swirl around them, threatening chaos or mayhem. It's Us vs. Them until the entire environment grows menacing and the lovers, too, are trapped in its lurking perils--perhaps simply in the dire straits of being alive. Although the dancers worked with their typical fervor, this piece didn't match the complexity and impact of the two works that followed. Nevertheless it made a useful curtain raiser, immediately assuring the audience, through the freshness of the choreography, that it was not going to be mired in the conventional.

Týnek's flaws? Nothing Bessie Schonberg, the late advisor to the realm of contemporary dance, couldn't have corrected in a minute: Sameness will dull your audience's perception, so . . . Don't use all eight of your dancers for three pieces in a row. Don't use dusky lighting for three dances in a row. And, while we're talking about dusk, don't encourage your costume designers to confine their palettes to muted grays and browns.

Apart from pointing out that many of Týnek's dances could benefit from further development, I won't attempt to guess what suggestions Bessie might have made about the choreography. She was a keen-sighted observer and a benign supporter; she could make anything better without undermining its creator.

Duŝan Týnek's Dance Theatre in rehearsal

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Still, I believe Týnek's frustratingly slow progress toward wider recognition is not due to artistic shortcoming but, rather, to practical factors. Emerging choreographers of the classical-ballet persuasion seem to have a good many opportunities to make and show their work, especially if they are attached to an important company. Contributing to the repertory of a junior company and creating a dance for a company's New Choreographers Evening are just two of the options. Contemporary dance troupes don't have the money to back such programs and many of them (like Paul Taylor's) are devoted entirely to the work of their founder. At the same time, ironically enough, the big ballet companies are absorbing the work of the best contemporary choreographers (Taylor, Tharp, Cunningham) because today there are few strictly-ballet choreographers as good as these. Now there's no way Týnek can change the situation on his own (though I devoutly hope he's doing whatever he can). It's up to the organizing contingent in the dance world--the folks who brought Fall for Dance into being, for example--to figure out the solution. Preferably soon.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Jonathan Burrows & Matteo Fargion / Danspace Project, NYC / November 3-5, 2011

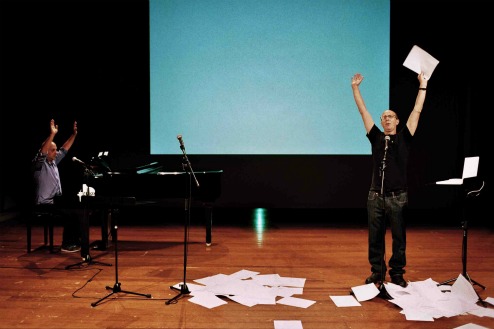

Shadowplay: Jonathan Burrows (l.) and Matteo Fargion (r.) in their Both Sitting Duet

Photo: Herman Sirgeloos

When the presumably odd couple Jonathan Burrows (dancer and choreographer) and Matteo Fargion (musician and composer) played The Kitchen back in 2004 in their Both Sitting Duet I titled my review (lots of description, some analysis, intimations of enchantment) "Less Is More." Seven years later, they're back in New York for three performances at Danspace Project, for which they may have been thinking that less was not quite enough. Opening night was essentially a double-header: their first success here was preceded by Cheap Lecture and The Cow Piece, two works, made in 2009, that New York hadn't seen yet.

Before I get to the more recent pieces, I'm reproducing my 2004 report for ArtsJournal because it sums up what I saw--and still see--in Both Sitting Duet.

IS LESS MORE?

Jonathan Burrows/Matteo Fargion / The Kitchen, NYC / March 11-13, 2004

Is less more? Answer: Yes, when we're talking about Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion's Both Sitting Duet. Performing the 45-minute piece they invented, the two guys sit on battered regulation-issue wooden chairs smack in the middle of a bare, black-box stage space. The chairs are congenially angled toward each other, as if set up for conversation. The men, who have a certain physical resemblance, are early middle-agers with compact bodies and keen, worn faces. Their costume--no-nonsense jeans, nondescript shirts and shoes--is the epitome of ordinary. You'd pass them on any urban street without a second look.

Each man has, at his feet, a notebook scrawled with words and symbols that he eyeballs regularly, as a musician does his score. Fargion is a musician; Burrows, a ballet-trained dancer and choreographer. Shortly after they've launched into their . . . tour de force of arm and hand jive, you can tell from their movement--even though they're executing the same gestures in unison, in canon, or as rapid-fire Q & A--who comes from which art. Burrows's execution is the more sharply focused, projected toward a presumed spectator. Fargion's, with its softer edge, seems inner-directed, has a slightly more subtle rhythm. Burrows powers his arms from his gut, while Fargion operates mainly from the shoulder, his midsection lax.

Here's what they do: shake their hands wildly in front of their chests, so their fingers look like sparklers; use one hand to count the fingers of the other with a child's deliberation, as if the answer might be in doubt; stroke their palms along their trousered thighs; palpate the floor with their fingertips; curl their fingers into vivid mudras that yield no explicit meaning; extend their arms in semaphore signals or (Burrows alone, while Fargion softly claps out a tempo) classical ports de bras.

A couple of times they stand up for a few seconds, even go so far as to turn in place, repeating a raucous cry; once they shift the position of their chairs so that one lies in the other's shadow. Such departures from what they've set up as the parameters of the piece have the impact of high drama--violent and haunting.

Most of the time they remain seated, their movement largely confined to their arms and hands, torso and head just going along for the ride. They make a lot of eye contact, though, and run through a gamut of facial expressions that suggest a ping-pong exchange of ideas and a brotherly relationship that's both challenging and complicit.

Will you believe me if I tell you this wasn't tedious? Far from it. Just the opposite. The more things remained, so to speak, the same--one man's move copied by the other, a single gesture repeated again and again by both--the more fascinating the whole business became. The secret--an open one, to be sure--lies foremost in the small, canny variations in rhythm with which the performers inflect each unit of basic material. Example: Delivering a rapid three-gesture phrase for one hand, the pair begins by working in unison, then lets its individual articulations go slightly out of synch in a loop that keeps returning to the original unison and departing from it again. It's like the hypnotic action of windshield wipers with a slight glitch in their mechanism.

Another part of the secret: The repertory of moves is adeptly structured, alternating between the small and the large, the fierce and the delicate, the agitated and the serene, the sounded (slaps, claps, pats, occasional stomps or monosyllabic cries) and the silent. In the silence--the piece has no conventional musical accompaniment, and the audience was rapt--the very scratching of a reporter's pen on her notepad seems an intrusion.

And then, rewarding one's alertness, there's the message (you might even call it the moral) of the piece: A close focus on replication paradoxically allows differences to emerge, minute states of otherness growing immense in scale or suggestive power.

Here's what Both Sitting Duet made me think of: Pairs of Parisian intellectuals, sitting in cafes, exchanging abstruse ideas for the fun of it. My uncles hunched over a card table, playing infinite games of pinochle at my grandmother's house, every Sunday afternoon of my childhood. Deft practitioners of American Sign. Obsessive-compulsives. Language teachers demonstrating the gestures that accompany voluble Italian. Merce Cunningham.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Two's Company: Burrows (l.) and Fargion (r.)

Photo: Alastair Muir

Now, what about Cheap Lecture and The Cow Piece? Both are dazzling, and they belong together. The first makes its point largely through words; the second, through absurdist deeds. Both ramp up Burrows' and Fargion's particular gift--articulation and offbeat timing in spoken language and body percussion--to such a virtuosic degree that a first-time onlooker's head starts to reel. I, for one, felt I was taking in only part of what was actually going on. I'd jump at the chance to see both pieces again, right now. Best of all, soundly rooted in the couple's earlier work, they move it along to more complex developments, refining and advancing their unconventional aesthetic.

Cheap Lecture is a loving mockery of sessions purporting to convey information--even wisdom--by a pair of professorial types. You've sat before them, puzzled or benumbed, in college or the halls of adult education. (Granted, this pair is dressed like handymen, but that costume is just these artists' trademark.) Each fellow, standing, speaks into his own standing mike, but the two thread their utterances into their partner's as if to represent a single person. Silences, little and large, make for the duo's off-beat timing, and their use of repetition owes much to Gertrude Stein. Each guy holds a sheaf of paper that is supposedly the script of his talk. Page by page, he drops it onto the floor when he finishes making one of his pointed/pointless points. Behind the speakers is a large screen onto which are projected the key words and phrases of their rant; these might be the notes taken by a dutiful listener, pathetically intent upon enlightenment. Be assured, though, that the B&F tone is neither bitter nor supercilious. Life is absurd, they're telling us, and we're all in it together.

Information Please: Fargion (l.) and Burrows (r.) in their Cheap Lecture

Photo: Herman Sorgeloos

The Cow Piece uses the same setting--but to another purpose. Burrows and Fargion stand behind a pair of laboratory-style tables, each of which has become home to a mini-herd of a half-dozen three-inch plaster or plastic cows. On an undercoat of white, half of them are spotted black; half, sienna. The men are their irresponsible shepherds, given to the intermittent playing of invitations to peasant-style dancing--on a harmonica, a mandolin, and (my erudite guest informs me) a miniature harmonium.

The men arrange and rearrange their cows obsessively and count them again and again like uncertain, if loving, parents. Farjeon even names his--Italian names, like Bella and Lavinia, that refer to his ancestry. As the pace of these doings and the energy put into them accelerate, the men--like very young children whose playing has gotten out of hand--escalate into gleeful cruelty to their cattle, knocking them down and, clever devils, hanging them on minuscule ropes made of string. Throughout the piece, the narrative is, accompanied by all the iterations, gestures, and skewed timing typical of the makers' style. The crazy antics and even wilder joy are horrifying and amusing at the same time.

Something I continue to find amazing about Burrows and Fargion's work is that many of its viewers think at first that they've stumbled upon little-known-talent--you know, just by accident. No such chance. The duo has performed its repertoire internationally, consistently intriguing its audience, and has been officially commended with honors such as a New York Dance and Performance Award (a "Bessie") and high-end commissions (for Burrows) from the likes of William Forsythe's Ballet Frankfurt and Sylvie Guillem. At first glance, the pieces don't seem to have any hidden ambitions but rather to be like something you yourself (or, more likely, a clever child) could fashion with one of those kits of 1001 click-together parts. The simplicity of means in Burrows and Fargion's work and the sheer fun that pervades it seduce you into loving it. All the while it's inexorably revealing its genius.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary