Seeing Things: October 2011 Archives

Morphoses / Joyce Theater, NYC / October 25-30, 2011

Remember Morphoses, the ambitious start-up company Christopher Wheeldon cavalierly abandoned after just three years in 2010, leaving the troupe's co-founder, Lourdes Lopez, to pick up the pieces? Last night, at the Joyce, it concluded the six-day run of its rebirth. If Bacchae, an hour-long piece by the Italian choreographer Luca Veggetti that constituted its sole offering, is any indication, we may have witnessed a second round of death throes.

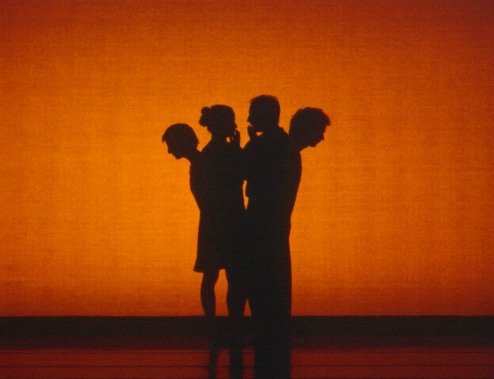

Scattershot: Frances Chiaverini in Bacchae, created by Luca Veggetti for Morphoses

Photo: Kyle Froman

As its title indicates, Veggetti's Bacchae claims to be based on the violent and profound Greek drama of the same name that was among the last works of Euripides, the towering fifth-century BCE playwright. (My colleague Deborah Jowitt offers a splendid survey of this background in her Dance Beat review for ArtsJournal.) If, however, you went to see Morphoses hoping to encounter in Veggetti's version the ancient classic's basic story--with its philosophical ramifications and theatrical punch--you were on a fool's errand.

Though he deigns to summarize Euripides' plot in a brusque just-the-facts-ma'am paragraph in the house program, Veggetti refuses to stoop so low as to represent any of the events in the play or identify any of the characters on the stage. Instead he offers highfalutin' pretentiousness in the form of sleek movement in a reduced vocabulary and posturing made to look runway-stylish.

The key ingredients in the choreography are bold gestures of the arms, strangely curved in at the wrist; borrowings from an advanced level of yoga (a practice surely Greek to the Greeks); and, worse of all, endlessly reiterated skids across the floor, as if the dancers were on kids' scooters, an effect made possible by their feet being sheathed in socks. The move has no decipherable context to give it meaning; the socks look absurd.

Throughout, apparently to create atmosphere--of dread? of great doings?--voices from nowhere intone words and phrases that, when they're not too blurry, still don't tell us much. There are also tactics , seemingly heavy with metaphor, that fail to give us the key to their lock. For instance, we first meet the flautist Erin Lesser, in a long stint of trying to animate an instrument taller that she is. Much time and breath are wasted on this absurdist passage, which includes assuming the overgrown flute is a percussion instrument. When Lesser appears later, she gets to play a real flute. What's the point of this?

Bacchae is also crammed with smart-alecky tricks that fizzle and arch devices that are simply ludicrous. A little wooden puppet--a strung-up version of those small jointed wooden figures that help visual artists get anatomy-in-action right--appears early in the piece and never returns to clarify its purpose. Veggetti might usefully have a look at Crystal Pite's Dark Matter to see how richly such an avatar can be used. And then there was the much-repeated effect of having the dancers enter the stage by crawling--awkwardly, too--underneath the yards of black fabric that curtained the three walls of the stage. I could go on; the list is substantial.

Footsteps: Chiaverini in Veggetti's Bacchae for Morphoses

Photo: Kyle Froman

In both its incarnations Morphoses has been, of necessity, a pick-up troupe. Its 11 current dancers form a modern ballet group deserving nothing but praise; to a one they're handsome, proficient, mature, and distinctly individual. Three dancers play the central roles in Bacchae. Frances Chiaverini has an extended solo that functions as a prologue, her long, strong, impressively flexible body stretching on the floor as if she were simply a dancer warming up. In the course of the show she's regularly the central--magisterial--figure of a segment, even when she's hovering on the dusky sidelines, watching it.

Gabrielle Lamb of the gleaming copper hair is paler and smaller. Although she's clearly strong, especially in held poses, she has a fragile, vulnerable air. She appears to be condemned by fate, projecting courage through passive endurance. Adrian Danchig-Waring (borrowed from the New York City Ballet) has the face and bearing of a long-ago Mediterranean potentate. You could imagine his head on an old Roman coin. Full-figure he appears at once entirely self-possessed yet gnawed by inner turmoil. Imagine how eloquent such dancers could be in worthy choreography!

Lopez's long-range plan envisions the troupe's appointing a different "resident artistic director" every year. This person (the Swedish choreographer Pontus Lidberg's name has been mentioned for 2012) will create or be the catalyst for a forward-looking work, alert to the possibilities of multi-media, which are already embraced in the dance world. The question remains, Will there be a next year?

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Fall for Dance / City Center, NYC / October 27 - November 6, 2011

The price of just about everything is escalating--food, college, shoes, diamonds, you name it. Yet one thing in New York has kept to its bargain rate. Tickets to the annual Fall for Dance festival at the newly refurbished City Center are still just $10 each. From October 27 through November 6 this year the Festival has offered two performances each of five different shows, each of them contrasting four soloists or groups of very different stylistic persuasions. Dance veterans and newbies beware: You've got to be quick on your feet in buying your tickets since Fall for Dance is famous not just for its range and affordability but also for its sold-out houses.

Last night I saw the first program, which presented the Mark Morris Dance Group, Lil Buck, the Trisha Brown Dance Company, and the Joffrey Ballet. The evening opened with Morris's 2003 All Fours, set to Bartók's String Quartet No. 4, played live. Admirably, Morris insists on this condition and is willing--and, thanks to his success, able--to pay for it. Essentially abstract, the dance appears to pit two communities against each other, then bring them to an uneasy reconciliation. The groups are identified by the color of their costumes; there are eight "blacks," four "whites."

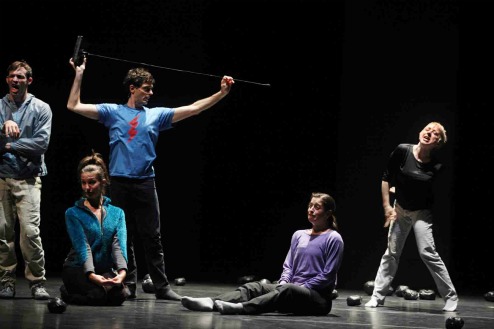

Profiled: Members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris's All Fours

Photo: Ken Friedman

The black crowd might be a gang possessed by evil, brain-washed into it perhaps, and ready to disseminate it, or so I assumed from the mechanical, staccato quality of their actions. The white contingent may remember what love is, but obviously harbors a deadly secret (indicated by their cautionary gesture of raising their fingers to their lips). It comes as no surprise that Morris never reveals what the secret might be; doing so would ruin the work's power. Paul Taylor operates with the same splendid motto: Never explain.

The rapprochement of the two contingents isn't rendered as clearly as their earlier opposition, which is presented as turf warfare. Once the two gangs tentatively start occupying the same space, it's hard to tell what might have brought them together. But then compromise is never as clearly dramatic as contention.

The choreography is full of astute references to other legendary modern dance choreographers. From Martha Graham Morris co-opts the pleading or praying gestures of folks in trouble; from Paul Taylor, the lumbering gait of the grotesques in 3 Epitaphs; from Doris Humphrey, the most gorgeous of the falls to the floor that she invented: from vertical to splayed-out supine on a single count.

The audience for All Fours may also find literary associations in the piece, whether Morris himself intended them or not. Eerily and wonderfully two of the black men function as clones, but not quite. The pair made me think of Tweedledum and Tweedledee in Alice's Wonderland as well as Dupont and Dupond (pronounced the same way in French, in English translation called Thomson and Thompson), the hapless detectives in the Tintin comics.

Typically Morris accumulates a series of gestures--some of them suggesting an attitude or an emotion, some perhaps arbitrary--and repeats them in deftly varied ways throughout a tightly structured dance. In All Fours it's thrashing arms, a hand cupped to the ear, fists with a single finger raised straight up, a woman standing on the thighs of a man who obligingly bends his knees to create her perch. You notice the ways in which Morris deploys this material and you think, Here's a guy who knows what he's doing.

My only problem with the Fall for Dance performance of All Fours is that the cast didn't seem to be working with the lusty commitment Morris fans have come to count on. Why I can't imagine.

The most fun and the greatest surprise of the evening was Lil Buck's The Swan, a solo, partially improvised, set to the Saint-Saëns music to which Michel Fokine choreographed for Anna Pavlova. Lil Buck (aka Charles Riley) wasn't wearing pointe shoes, though his limber gyrations in sneakers often whisked him onto pointe and demi-pointe. What he does is a form of urban street dancing called Memphis Jookin' and he's a born star.

Articulate Ankles: Lil Buck, both dancer and choreographer for The Swan

Photo: Erin Baiano

Accompanied by an onstage cellist (Joshua Roman) and a harpist (Riza Hequibal Printup) who, beautifully lighted, suggest a corner of Heaven, Buck (the "Lil" seems to be an honorific in his trade) makes a calm entrance. Then, energy coursing through him, he delivers arm gestures that suggest, simultaneously, both the rippling wings of a swan (at least as imagined by Fokine, and Ivanov before him) and the water that is the bird's element. His whole body is preternaturally fluid. He has the most articulate ankles imaginable and the mobility of a contortionist in every joint. Buck's Swan meets its death as the dancer slowly ties his body into a knot from which there is no escape.

There's more to Buck's performance than a lithe body, physical eccentricity abetted by grace, and a charismatic stage presence. He seems to identify with the swan in its plight, giving the creature the same kind of dignity and pathos that I once saw Galina Ulanova achieve in the Fokine version.

Right after the performance I went to YouTube, that gallery of innumerable uncurated images, to see and learn more. I saw that while the vocabulary of Memphis Jookin' is small, the joyous defiance with which its inadequately privileged practitioners break the rules of Establishment Dancin' is immense.

The most sublime contribution to the program was Trisha Brown's Rogues, new work, set to music by Alvin Curran, that looks like part of something larger, still to be created. As it stands, it's an exquisite duet performed by Neal Beasley and Lee Serle, one a head taller than the other. In gray jerseys and skinny jeans--typical Brown workaday garb--they do much of their dancing in unison or at least in canon. This tactic, of course, reveals the differences between things that might be carelessly considered the same.

As the dance progresses, Brown subtly and slyly persuades you not only to notice the differences between the two men but also to rejoice in them. Just to begin with, the shorter fellow is stockier, the taller one lankier, and these disparate builds affect the way they move and the very texture of their movement, even when they're synchronized.

The men performed very faithfully in Brown's style--fluid yet full of unexpected angles, understated and unaffected, yet with unwavering focus. They did remarkably well, as far as anyone can replicate a uniquely personal style. As yet, no one has fully succeeded. Onstage Brown was a marvel, tossing off sneakily complex moves as if she were sauntering down the road and performing feats of concentration as if she were part of a desultory conversation. Her remarkable physical sensitivity, her intellectual acuity, and her wry sense of humor make imitators look lazy. The "next" Trisha Brown would have to be an original, just as she herself is.

The Joffrey Ballet, which way back when was resident at City Center, flew in from its Chicago home to represent classical dancing. To me, Edwaard Liang's Woven Dreams, set to music by Maurice Ravel, Michael Galasso, Benjamin Britten, and Henryk Gorecki, seemed essentially unwatchable. Svelte muscular bodies in sleek costumes rendered a slew of balletic conventions that lacked a coherent structure and afforded no clues as to musical inflection and emotional subtext. The dancers--hardworking if still needing a jot more technical polish--seemed to be, literally, just going through the motions.

The piece begins with a group emerging from an enormous, heavy web (designed by Jeff Bauer, who also provided the ice blue Vegas-goes-minimalist costumes). Oh so predictably, the web rises to serve as a ceiling and, many moons later, descends to hover over the performers' heads, signaling the end of the ballet's meaningless maneuvers.

Many of us in New York miss the Joffrey but Woven Dreams made me recall how many indifferent-to-godawful ballets the company has always had in its repertory. When Robert Joffrey was alive (he died in 1988), he fostered a rep in which easy-looking ballets, mostly by the facile Gerald Arpino, were programmed side by side with neglected but fascinating one-acters of the past by the likes of Kurt Jooss and Léonide Massine as well as more current masters like Ashton and Balanchine. At the same time, Joffrey commissioned work from gifted choreographers on the cutting edge, notably Twyla Tharp and Laura Dean. He remains a hard man to replace.

I should say here that a slot on a Fall for Dance program doesn't let you fairly size up a company. It was never meant to. Fall for Dance offers pleasure and stimulation. Intrigued viewers must take it from there on their own.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Necessary Weather / Baryshnikov Art Center: Jerome Robbins Theater, NYC / October 27-29, 2011

Light--silent and impalpable--is almost essential to theatrical dance. Jennifer Tipton has been its master for over four decades, creating atmospheric marvels for drama and opera as well. In 1994 she dared to ask herself, What if light were not just a significant accompanying element but a star player in the show? The answer became Necessary Weather, in which she collaborated with two distinguished postmodern dancers, Dana Reitz and Sara Rudner, for an hour-long piece presented at the Kitchen. In a quiet way it became legendary and was finally revived last year at the Baryshnikov Art Center. This year it has been incorporated into Lincoln Center's White Light Festival.

Sara Rudner (l.) and Dana Reitz (r.) in their and lighting artist Jennifer Tipton's Necessary Weather

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Note: All photos show the present production.

I skipped last year's revival because I couldn't imagine anything as beautiful and moving as the original production. Finally, last night, I succumbed and showed up at BAC's sleek Jerome Robbins Theater--and now regret the move. Why? Because 17 years later, everything has changed considerably: I've aged; so have the dancers. All three of us are surely aware of what the Beatles considered old in their charming song "When I'm Sixty-Four." What's more, the culture has shifted enormously. Innocence, wonder, and vision have lost yet another chunk of the popularity they enjoyed in the Sixties.

Here's what I said about Necessary Weather in New York magazine back in '94:

Downtown at the Kitchen, a distinguished trio comprising the dancer-choreographers Dana Reitz and Sara Rudner and the lighting designer Jennifer Tipton presented a haunting hour-long work called Necessary Weather. An evocation of subtle atmospheres, the piece was an equal collaboration of the three (early in her theatrical life, Tipton was a serious dance student). Still, their specialties were evident: Rudner's and Reitz's sharp, delicate articulation and sensuous fluency; Tipton's ability to make illumination create a world of wonders.

The raw materials were rigorously simple: rough charcoal walls and smooth slate-gray floor, light almost exclusively untinted, the two performers dressed in oversize translucent white shirts and loose white trousers, no aural accompaniment beyond ambient sound. The light spilled--from overhead, from the sides at various heights, from half-hidden sources at the edges of the floor--in soft, wide washes, in tight columns ending in sharply defined circular spots; now dim, gentle, and mysterious, now glowing with ever-increasing brightness as if to reveal bare-bones truth. Each luminous landscape, anchored by the motion of the women--who themselves began to seem impalpable--was like a different potent dream.

At one point, the two figures skirted the perimeter of a large disk of light, cautious but intrigued, like members of a tribe approaching the sacred arena of their ritual. Then Rudner moved into the bright space and suddenly, shedding its ominous aura and acquiring gaiety, it changed into a circus ring. There she seemed to enter a private world of release and delight, though Reitz was duplicating her moves in the near-darkness just an arm's length away. For me, passages like this recalled childhood episodes in which my mood was profoundly affected--and my imagination activated--by the light conditions at different times of day and night, in different seasons and weather. As this singular work proves, theatrical artifice can be the means of recapturing primal experience.

Here are a few of the thoughts I had about the current production:

Rudner (l.) and Reitz (r.) illuminated by Tipton in Necessary Weather

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Sara Rudner, surely the silkiest dancer of her generation, was for many years, as a colleague of mine recently called her, Twyla Tharp's muse. Miraculously, she's retained a good bit of her earlier fluency, but now you see some of the effort involved, especially when she moves from the softness and calm that pervade Necessary Weather into a spate of the crazily swift, complex dancing she did for Tharp.

Tipton's encyclopedia of light effects constitute a telling tour de force on their own. They really do demonstrate how lighting evokes mood in the theater, just as it does in nature. Even more amazing is the fact that she works almost exclusively with black and white (light and dark) and all the many grays in between. Technicolor effects don't enter the picture. A little peach, a little gold--that's all you really notice. Meanwhile, the shifting intensity of brightness and dusk leaves you breathless and conjures up memories of events in your own life that occurred under just such states of illumination.

The choreography itself is not very interesting. Its vocabulary isn't large, and too much attention is given to the arms (wafting airily) and hands (overactive, as if they were trying to defect from the arms to which they're attached). The torso has little to say. The legs and feet are vastly under-challenged. Both Rudner and Reitz pace the floor sensitively (they've perfected the cat's-paw tread and the rhythms of walking), but anything in the hop, skip, jump department has been avoided.

Tipton is acutely aware of how light falls on dancers, not just in terms of how it makes the audience see them and interpret their action, but what it "tells" the dancers themselves. Professional dancers learn from performance how to accept its embrace or hide from it--or in it. From Paul Taylor in the modern wing and Irina Kolpakova on classical ballet's turf, I've heard detailed, impassioned advice to dancers about being aware of how the light strikes the cheekbone.

Rudner (l.), Reitz (r.), and Tipton's collaboration, as seen in Necessary Weather

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Rudner and Reitz wear the all-white costumes I recall from the original Necessary Weather: sheer, loose tunic-length shirts over a torso-hugging singlet and easygoing trousers. Their feet are bare. In one segment of the dance Tipton's lighting turns them into pale, barely visible wraiths, moving around restively, like the ghosts that frighten your four-year-old at night, just after you've fallen asleep. As I write this, I realize that the piece hasn't completely lost its enchantment for me. And I hope that others may have the experience the choreographer Christopher Caines described to me today: "I was the rehearsal-process light-board operator for the original production of Necessary Weather, a life-changing experience. I have never had the same eyes since."

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

The Forsythe Company / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Brooklyn, NY / October 26 - 29, 2011

I've always shared George Balanchine's idea that a dance should speak for itself. William Forsythe certainly doesn't. At BAM last night The Forsythe Company, based in Germany, opened a four-day run of his enigmatically titled work I don't believe in outer space, created in 2008. Vigorously applauded by a largely pre-middle age audience, it would have remained as impenetrable to me as its title, had I not read the reviews and previews from its earlier showings in London.

Here's the story I pieced together: The choreographer's 60th birthday made him conscious of his own mortality. He decided to make a piece to explore the almost unfathomable idea of leaving the world, of simply being absent from everything he knew. (By odd coincidence I had that experience once as a child and naturally have never forgotten it. The notion of non-existence can be terrifying.)

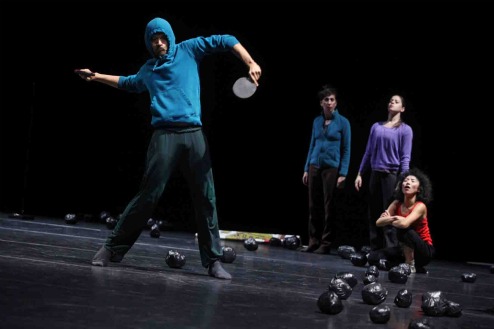

The Forsythe Company in William Forsythe's I don't believe in outer space

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

In conjunction with considering his own past and his future prospects, Forsythe explored the idea that the domain he'd be leaving had no meaningful structure or even concrete reality. Things fell apart, came together haphazardly, fell apart again, came together again, and then, maybe, exploded. Everything that happened, happened "as if by chance." Yet, somehow, life was very much worth living. All of this was accompanied by the notion that at times the goings-on could be amusing.

I don't believe in outer space uses 17 dancers; live sound and recorded sound (to which the dancers often lip synch); music by Thom Willems; a plainspoken set with dimly lit upstage portals for appearances and disappearances; and, strewn helter-skelter on the stage floor, numerous rough-hewn balls made from the black gaffer tape the backstage crew uses to install flooring and then discards after the show. The balls look like miniature meteorites, fallen from--well, outer space.

The star of the show is Dana Caspersen (Forsythe's wife). She plays a witchy figure who survives any disaster because of the unquenchable force of her rage. She's fueled by fury, like creatures of primal evil in the Brothers Grimm. Once you recover from the shock of her presence as this character--the hands like vicious claws, the squatting walk, the loud, grating voice--you're lured into a shamed admiration of her daring tactics and their success. Caspersen also plays this demon's alter-ego, a Little Goody Two-Shoes housewife, who doesn't stand a chance.

Once the major ideas of the piece are presented, Outer Space continues as a series of vignettes. They flow into one another in a manner so subtle that their order seems random--as strings of events so often do in what we think of as real life.

The Forsythe Company in Forsythe's I don't believe in outer space

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

In a scene that Alice might have witnessed in Wonderland, two guys play ping-pong. Of course there's no table, no net, and, what's more, no ball. But they man their racquets in tandem with the exact sound of the celluloid ball striking an invisible surface. Of course, life being what it is, this absurd match becomes a fatal competition. Even when one of the men captures his partner's racquet, the two manage to go on "playing."

At intervals we see a handsomely built male couple--doing what exactly? Making love standing up (more or less) or fighting, in close. The viewer is left to choose which or to settle for the obvious--both. The pair is passionately locked in combat.

Now and then, a petite, fleet woman with a mop of curly dark hair, flashes through the space wearing something red. She's like a spark of fire briefly animating the prevailing darkness.

As time goes by, events get increasing violent and/or surreal. Finally Yasutake Shimaji introduces some welcome calm into the raucous proceedings. A Japanese-born man, slender and supple, he has a long, haunting, less-is-more solo in which he's all self-containment and quiet grace.

Suddenly, unexpectedly, matters turn almost sentimental as the narration becomes a long, loving citation of all the things in life you relinquish when you disappear. It may bring tears to your eyes ("no more years, calendars, planning"). You may think it's sappy ("no more running with your brothers on a railroad track"). I thought the most telling entries on Forsythe's list were the ones connected to dancing: "no more speed, direction, going, different ways of going"; "no more trees, Fall/fall, things that fall." And then, the most searing loss of all: "No more touching."

The 17 dancers who make all this happen are a fabulous bunch. They deserve accolades for power, precision, flexibility, and individual presence. I'm certain that, if I saw them more often, I'd grow fond of the personas they project, just as I did with the performers in Pina Bausch's early works. Meanwhile, it's thrilling to see that nearly all of Forsythe's dancers have their muscles on high alert and that they seem devoted to their boss's vision. The sight of the full cast simply running cross-stage at top speed can convince you that it's the journey, not the arrival, that matters.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

New York City Center Opening Night Gala / New York City Center, NYC / October 25, 2011

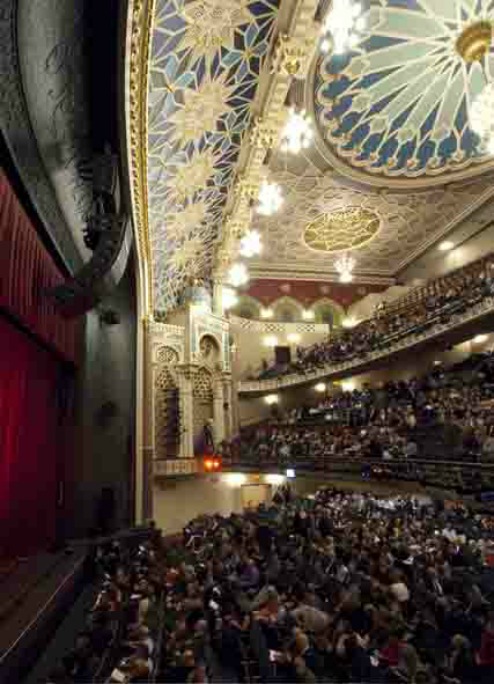

City Center renovated, view from house left

Photo: © Aislinn Weidele / Ennead Architects

Last night's celebration of the renovation and restoration of the New York City Center assured the theater's aficionados of dance, music, and drama that they would still be spared having to "walk a mile for a camel." Before it became an arts center "for the people" (meaning affordable), the building, called the Mecca Temple, was a center for the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. It was not a house of worship, however, but instead a highfalutin clubhouse for a fraternity of Freemasons aiming to do good through charitable works and to enjoy each other's company. Its rituals involved exotic costumes and props. Its decor was based on the concepts of "Arabia" captured in the Moorish Revival style. Hence the camels on the site's walls.

Subsequently obliterated by a thick coat of All-Purpose White, the camels--once taking their riders on prosaic journeys--are now re-imagined as the mounts for more ecstatic pilgrimages in a pair of dreamy pastel-hued murals at either end of the lobby on the mezzanine level.

City Center, Grand Tier lobby, with the new version of the camels

Photo: © Aislinn Weidele / Ennead Architects

At first glance a visitor will notice that the City Center has been made visually more handsome--and striking--all the while wholeheartedly, and with tactful subtlety, respecting its old look, which was admittedly hokey. While architectural changes have been executed for urgent practical reasons, much of this refurbishing has been accomplished by a massive paint job. From the ceiling of the outer lobby through the auditorium itself, the patterning and palette of Moorish decor has been used as an inspiration. Repeated geometric designs are now larger and bolder, while the palette of burgundy and a deep blue just tinged with green has been intensified. Both modifications contribute to the illusion of stained-glass windows set alight by the sun. Touches of gold have been added, while the proscenium has been darkened with slate gray, creating a frame of mystery around what happens on stage. Inside the auditorium, seating and carpeting echo the prescribed palette.

The only misstep is a clumsy and unfathomable video installation in the inner lobby, perhaps an attempt to add the visual arts to the house's offerings. I'd say everything else was a success, intelligence and taste having been used to avoid innumerable pitfalls. Admittedly, I'm one of the no doubt few people who reveled in the City Center's shabbiness. I still remember the day that Robert Joffrey, trying to escape doing the interview he had promised me, took me on a long tour of the dusty, gloomy backstage realm and suddenly halted to say, in wonder, "Can you imagine all the things these walls have witnessed?" Yes, I could: Balanchine and his New York City Ballet, just to begin with.

But progress is unstoppable. The house has been made more comfortable for performers (improved backstage accommodations and a top-notch sprung stage floor) and for spectators (a lighted and heated marquee, improved sight lines, seating with more leg room and more booty room, expanded restroom facilities, and a second elevator).

The new look was designed by Ennead Architects, took more than half a decade to execute, and will end up costing a reported $57 million. Since the City of New York was absorbing nearly half that amount, it seemed only reasonable that Mayor Bloomberg should get to open the gala evening by conducting the orchestra of the house's Encores! series in the "Star-Spangled Banner." This being the national anthem, the audience--packed with splendidly attired 1%-ers--had to stand up (correct) and applaud (incorrect, but common practice). Still, though he added a brief, amusing speech, the Mayor should probably not quit his day job.

City Center renovated, view from house left, with front of stage

Photo: © Aislinn Weidele / Ennead Architects

The stream of top-notch entertainment that followed, introduced by commentators often as starry as the artists, was adeptly put together by the Broadway choreographer Kathleen Marshall. Each item was terrifically done, so I'll just report them in order of appearance. Here goes:

Robert Battle, Judith Jamison's successor as artistic director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, introduced an excerpt from Ailey's Pas de Duke. Linda Celeste Sims and Matthew Rushing danced it with the kind of musical acuity, sexiness, and sheer know-how that only veteran performers can achieve.

Alex Bernstein, Leonard's son, speaking for the City Center's classical-music scene, gave us the violinist Joshua Bell, a one-time child prodigy who has actually fulfilled his early promise, combining an energetic attack with a honeyed tone. Then came the mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves singing "Mon coeur s'ouvre à ta voix" from Samson et Dalila, convincing her hearers that great emotions are within ordinary people's reach.

An admirably self-effacing Sara Jessica Parker pointed out, correctly, that the City Center was best known for its dance attractions. As evidence, if any was needed, Wendy Whelan and Ask la Cour of the New York City Ballet (long housed at City Center), performed the celebrated duet from Christopher Wheeldon's After the Rain. Whelan was all fragility and flexibility; la Cour made a reverent Prince of Tenderness.

Keeping things in the family, the actor Matthew Broderick (Parker's spouse) spoke for musical theater, introducing three dynamic singers--Donna Murphy ("I Happen to Like New York"); Brian Stokes Mitchell ("It Ain't Necessarily So); and Patti LuPone ("Everything's Coming Up Roses").

Brian Williams, TV newscaster extraordinaire, extolled the City Center's ever-growing outreach program and interviewed two young students aiming for careers in the arts (Tessa Horn and Makaela Martinez) who had benefited significantly from professional artists' visits to their schools. He survived the danger all actors fear--being upstaged by children--but just barely, so all three came up roses.

For a finale, a chorus of singers who have appeared in the house's Encores! programs, sang "Take Care of This House." The orchestra, which had done yeoman's duty throughout the program, playing onstage, came in for its well-earned share of the applause.

When the City Center is looking for its next project, it might usefully try fulfilling the job of a "people's theater," which it once was. For the first performance I saw there, I sat in a front and center orchestra seat for $1.25, which my modest adolescent's allowance covered several times over. I remember this because I was seeing the New York City Ballet for the first time and, while I had succumbed to a few childish crushes, it was the first time I really fell in love.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Suzanne Farrell Ballet / Joyce Theater, NYC / October 19-23, 2011

The Suzanne Farrell Ballet, named for the transcendent dancer who was George Balanchine's last muse, celebrates its 10th anniversary this year. Ironically, after a decade of generously favorable response to the group's work, some observers are questioning the wisdom of the enterprise's very existence.

Sarah Kaufman, the Washington Post's Pulitzer Prize-winning dance critic, sums up the situation clearly in her review of the troupe's showing at Kennedy Center in DC (the Farrell Ballet's official home), which directly preceded the present New York run. The Center's support for what became the Farrell Ballet had been urged by James Wolfensohn when he was chairman of the Center's board. Like so many of us, he had been inspired by the ballerina's incomparable dancing.

Thanks to Farrell's unique experience with Balanchine and her own vision and skill, the company she evolved over the past decade has consistently offered passages of sensitive, selfless, profoundly musical dancing. Nevertheless, it remains essentially a small pick-up group that can work only sporadically with Farrell. Inevitably, few if any of its dancers have been of the highest professional caliber. Under these circumstances, which are dictated by well-intentioned yet insufficient funding--and the absence of a Lincoln Kirstein clone to guide its growth--the organization can't hope to develop even as far as an aspiring regional ballet. "The questions now are," Kaufman concludes, "Could Farrell's talents be better used? And could [Kennedy Center's] money be better spent?"

Once it was clear that the New York City Ballet, under Peter Martins, didn't care to have Farrell around in her ideal role--coaching the dancers in the Balanchine repertory--I once hoped another sort of plan might work. What if three companies ripe for and worthy of what she can offer--Miami City Ballet, just for example--each agreed to hire her for a residency of three months per year, during which time she would coach and teach company class, imparting her deep understanding of Balanchine's principles? This was a pipe dream, my colleagues insisted; logistics alone would make it impossible and the present state of the economy would make it unlikely.

So dance fans are left with what Farrell can do with the resources she has. What I saw on the opening night of her company's New York run was disheartening. The ballets performed were Haieff Divertimento (1944), which Farrell had reconstructed; the pas de deux from Diamonds (1967), in which she originated the ballerina role and hasn't been equaled yet; Meditation (1963), the first ballet Balanchine created for her; and the justly renowned Agon (1957).

As a curtain raiser--a meet-and-greet affair, introducing the dancers to the audience--the light-weight Haieff Divertimento would have been just fine if only Farrell's dancers had the ability to toss it off with ease technically and the principals had invested in it dramatically.

The work for the four-couple corps and a central, unpartnered man is dotted with spiffy little bows from one dancer to another and from the dancers to the audience. You see immediately that this is the work of Balanchine because of the swift, crisp footwork, the inventiveness in the use of formal classical steps, and the liveliness and logic of the stage patterning. All of this reminded me of the perkier sections of the more substantial, and equally arch Danses Concertantes (1944; revised 1972).

And then, at the heart of the piece, we get the Romantic Balanchine. The man who lacked a partner meets the one destiny has chosen for him. He yearns to possess this sylph or muse who, as women of her ilk do, keeps floating away from him. The best that can be said for the Farrell crew's execution of the choreography is that Kirk Henning was promising as the main guy and everyone tried really hard to bring it off. The problem here--and throughout the program--is that effort is just what you don't want to see in a performance.

The pas de deux from Diamonds, the concluding section of the three-part Jewels, revealed most clearly what Farrell has been able to accomplish with her dancers and why the deck is stacked against her. Balanchine created the ballerina role on her and her dancing persona. Her grandeur, her lushness, her daring, and her potent dance imagination are incorporated into its design.

As in every ballet Farrell has mounted on her company, her coaching has clearly been superb and miraculously without ego. But she is working with people (here Violeta Angelova, partnered by Momchil Mladenov) who are dancing the coaching, phrase by phrase, step by step, as if they had a microchip containing Farrell's wise, detailed, and objective instructions embedded in their bodies. The dancers operate as if they understand these instructions and respect them but they can't follow them--or, when they do--can't make them cohere. The results include missteps, disjointedness, and a woeful absence of confidence and spontaneity.

Agon was all too obviously beyond the technical abilities of Farrell's dancers, and yet its timing was, in every detail, as deliberately strange and adept in its relationship to Stravinsky's spare, compelling score as it had been at the ballet's premiere. I remember being one of the astonished witnesses of that first night, merely a teenager but able to recognize that Agon was what the City Ballet was "about."

The ballerina role in the climactic pas de deux was created on Diana Adams (partnered by Arthur Mitchell). Farrell later inherited the part and now has assigned it to Elisabeth Holowchuk, who performed leading roles in three of the four ballets on the Joyce program. Holowchuk is an accurate dancer but, lacking both inherent drama and sensuousness, she simply doesn't register as a theatrical personality.

The most relaxed dancing on the Joyce program came with Meditation, made for Farrell when she was still in her teens. It's a duet that's a man's (Everyman's? The choreographer's?) naked confession of love for the dream woman he can never fully possess. It registers as a powerful rush of emotion (the Tchaikovsky score helps a lot), leaving little memory of specific steps and or stage patterning. Performing it, Holowchuk managed to entertain the possibility of expressiveness while Michael Cook was convincing through his authenticity and mercifully unpoetic. Any guy could find himself in this situation, he suggested. And this is certainly true--if only because unanswered love can be as emotionally gratifying as love fulfilled.

Shoring up the sporadic performances of her troupe, Farrell has contrived projects that are supposedly do-gooders for the dance community. Borrowing dancers from other companies to fill out the ranks of her necessarily small troupe is claimed to enlarge the visiting dancers' opportunities. Does importing more proficient dancers than she has to lead a production fall into the same category? Or is it evidence that the Farrell Ballet is not in a position to produce stars from its own ranks?

Another undertaking, reviving Balanchine works previously thought to be lost, presumably rescues them from oblivion. But Balanchine, an undeniably productive and resourceful choreographer, himself allowed these works to disappear. Often he recycled the best inventions in them when he made a new ballet. In viewing Farrell's reconstitution of the "lost" works, Balanchine fans with long memories can enjoy the parlor game of seeing where some phrases or effects showed up in subsequent ballets--reworked, refined, and elaborated in their new context.

Farrell's projects, especially when given formal names like the Artistic Partner program and the Balanchine Preservation Initiative, may engender respect for her company and elicit significant funding. But they are, in the end, essentially social work and scholarly endeavor, not art.

Farrell's dancing was an immense gift to the world. People who never had the chance to see it "live" fall in love with it via video alone. Once a ballerina who couldn't be surpassed, Farrell subsequently demonstrated her extraordinary ability as a teacher and coach of Balanchine's style and repertory. Surely she's earned the opportunity to function at a level that corresponds to her gifts.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary