Seeing Things: June 2011 Archives

Royal Danish Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / June 14 - 19, 2011

On the final leg of its ambitious coast to coast American tour, the Royal Danish Ballet played New York--the city least likely to let the troupe's legendary charm dissuade fans from seeing its problems. A central one is repertory. As Nikolaj Hübbe, the company's artistic director--and an energetic publicity machine--are telling the world at every turn, the RDB hopes to redefine itself by combining cutting-edge contemporary work with its custodianship of August Bournonville's ballets, performed with regard to the unique style forged by the great 19th-century choreographer. The program offered on the first two nights of the six-performance engagement was not entirely convincing.

Down with Classicism! The Royal Danish Ballet's Alba Nadal and Tim Matiakis in Jorma Elo's Lost on Slow

Photo: Per Morten Abrahamsen

If Jorma Elo's Lost on Slow, made for the Danes in 2008, is any indication of the RDB's eye for achievement at the cutting-edge, we're in bad trouble. Elo's response to the ill-assorted passages of Vivaldi he's co-opted for accompaniment is simply his familiar spastic perversion of classical dance givens--order, harmony, flow, and, as appropriate, beauty.

Three pairs of dancers, looking too far gone for relationship counseling, delivered this material (including a Munch-like silent scream from a lady being lifted by her cavalier) with determined precision. This made them look so frozen and mechanical that, gargoylish though they appeared, they probably couldn't pass the entry exam for Scandinavia's celebrated School for Trolls, which requires some capacity for feeling.

What, I wondered, is the obligatory mid-section pas de deux meant to convey? Crippled emotion? The impossibility of human communication? These are hardly up-to-date themes. Granted, the Vivaldi occasionally lures Elo into crafting a fluent phrase or two, but overall the choreography spurns connections. It's just one weird gesture after another.

I feel obliged to report that on both evenings that I saw Lost on Slow, the audience applauded the piece with all its might.

Given the agenda Hübbe is proposing for his company, the inclusion of The Lesson, based on a one-act Ionesco play and choreographed by Flemming Flindt in 1963, may have seemed an odd choice, particularly as the curtain-raiser on opening night and the number of performances it was given. The intelligentsia loathes it; the general public finds much to enjoy in the melodramatic horror story of a psychotic middle-aged ballet master giving a macabre private lesson to a dance-entranced nymphet, apparently just one in a long series of victims. To be sure, this ballet is not high art, but it's a handy vehicle for a company famous for dancers who can act.

Lady Killer: Thomas Lund in Flemming Flindt's The Lesson

Photo: Martin Mydtskov Rønne

Plot-wise and mood-wise, it outdoes Black Swan at every turn. The setting (wonderfully designed by Bernard Daydé) is a picturesque old ballet studio with a profusion of mirrors, where a rigid female accompanist prepares for the pupil's arrival. The girl is infatuated with dancing and pretty good too, as it turns out, at incidental bits of sexual provocation. Needless to say, much is made of the gleaming pink pointe shoes that are the symbol of her trade.

From the moment the ballet master enters the room, it's clear from his twitching, face-averting, obsessive behavior that he's certifiable. Putting the pupil through her paces, which are increasingly demanding and increasingly bizarre, he couples furtive sexual advances with escalating violence. To make a long story short: Reader, he strangles her. The pianist, his abettor and perhaps an early victim who managed to escape alive, helps him dispose of the body just as the next student is impatiently ringing the studio's doorbell.

The Lesson fielded no fewer than three men for the role of the ballet master--Johan Kobborg, Mads Blangstrup, and Thomas Lund--and each was remarkable, offering an interpretation that was very much his own. My favorite was Lund, who was the most realistic in his madness and thus the most terrifying. The ballet master's curdled psyche evident throughout his body, Lund could convince even a veteran viewer of the work that the monstrous events were really happening, to real people, possibly even right now.

As the student, the striking Alexandra Lo Sardo gave a vivid--perhaps too vivid--portrayal of the girl in the traditional vein (of a young woman whose very personality invites trouble). Ida Praetorius, a petite, fair-haired apprentice with the company, still all legs and wide eyes, offered a more innocent, even childlike, take on the character, which I found moving.

Gudrun Bojesun, alternating with Mette Bødtcher, enriched the character of the pianist by adding a surging flow to the robotic moves the choreography assigned her and a dramatic subtext that enhanced the sense of a mysterious and ghastly relationship with the serial killer.

The best thing that can be said about Georges Delerue's made-to-order score is that it does its job.

When it comes to the Bournonville heritage--the Royal Danes are its custodian, just as the New York City Ballet is of the Balanchine legacy--the company is still unable to find the right way to use it.

The most significant evidence of the Danes' current attitude to Bournonville was unveiled at the Kennedy Center in DC, prior to the New York City engagement. The performances in the capital were devoted solely to Hübbe's drastically "new" versions of Napoli and A Folk Tale, two of the three most significant Bournonville ballets extant. Several critics were very tolerant of them; I wasn't and will explain why, in detail, in a separate piece, to come.

Remembrance of Things Past: Gudrun Bojesen reincarnates Bournonville's Sylphide

Photo: Martin Mydtskov Rønne

In the Apple, Bournonville was represented by La Sylphide, the ever-mounting dance excitement that concludes Napoli (which never fails to thrill,) and Bournonville Variations. This last is a new concoction--thought up, arranged, and staged by Hübbe and Lund, the company's Bournonville expert as both dancer and instructor. It's made up of excerpts, parceled out among nine men, from the so-called Bournonville Classes. These are six set classes--one for each day of the work week--that were put together by Hans Beck, a successor to the great man, mostly from consultations with dancers who had worked under Bournonville. Believe it or not, these classes, in which each exercise was accompanied by a popular tune, were used for decades as the training system for the company and the students being schooled for it.

Originally the classes were transmitted via the monkey-see, monkey- do system from one generation of dancers to the next. In 1979, the classes--and their accompanying music--were scrupulously researched, then published as texts through the efforts of Kirsten Ralov, RDB ballerina, teacher, and stager. A quarter-century later, the classes were recorded as DVDs. Although the videos are duly supported by a pair of books, it's the availability of the moving images that makes the material, once a kind of professional secret, accessible to just about anyone. Even you, even I, can try out the classes alone at home in our spare time (though I would hardly recommend it).

For the RDB's dancers and students, the unavoidable boredom of doing, say, Tuesday Class every single Tuesday from as early as the age of six until their retirement in mid-life, was alleviated, at least in the adult echelons, by the men's creating naughty ditties that they sang sotto voce as they executed the amazingly convoluted chains of steps. "If you can dance Bournonville, you can dance anything," it is said.

A real Bournonville class performed by professional or pre-professional dancers is, like a Martha Graham class performed by adepts, a thing of beauty and awe for the spectator. For their Bournonville Variations Lund and Hübbe got it all wrong from the moment they thought of theatricalizing the material. What might have worked would have been a demonstration, plain and simple, of a single full class (minus the Bournonville barre, which seems absurd--and even dangerous--to today's dancers), performed in the starkest of practice clothes, with women admitted to the club. (The set classes offer piquant alternatives according to gender for certain enchaînements.) But no, the perpetrators had to make it macho--something only guys could do, to reinforce the idea that the Danes produce these incredible male dancers (which they do). They also felt they had to make it look like a ballet (which it doesn't). It has no structure, no narrative or even subtext, no point whatsoever.

Bournonville Mashup: Alban Lendorf and Alexander Stæger in Bournonville Variations, idea, arrangement and staging by Thomas Lund and Nikolaj Hübbe

Photo: Costin Radu

Perhaps to conceal the fact that their smattering of excerpts doesn't cohere, Lund and Hübbe gussied it up with glittery black costumes (blame Annette Nørgaard) in the wannabe provocative sex-and-death vein (are the faux-leather pleated skirts that the guys wear at one point a reference to the kilts of La Sylphide?) and raw lighting in garish colors (blame Anders Poll) that Jennifer Tipton would surely condemn as dumb and vulgar past forgiveness. Martin Åkerwall's music, claimed to be based on the original accompaniment to the exercises, is unrecognizable as such.

Two of the nine dancers stood out: Alban Lendorf, a forceful presence, who stands out in everything he does, and, especially, Lund himself, who has the timing, the ballon, and the calm and tenderness needed for the lyrical phrases in the material as well as the ability to make the more devilish challenges look like an impulsive expression of joy. The others ranged from pretty damn good to not really up to it, the latter revealing the sad fact that Bournonville dancing is no longer the company's top priority.

The Danes in Italy: Susanne Grinder and Ulrik Birkkjær in the tarantella from Act III of Bournonville's Napoli

Photo: Costin Radu

More justice was done to Bournonville by an excerpt that concluded the third act of Napoli, which was relatively protected from Hübbe's changes to the full ballet. (The most flagrant of renovators may turn shy when it comes to meddling with national treasures.) Yes, a bland interpolated solo for the hero and heroine dampened the ever-heightening vivacity for a few minutes. And it was foolhardy to use the newfangled ending in which the lovers ride off after their wedding reception on a glossy white motorcycle instead of the original's peasant car crammed with bouquets from the pair's friends, two little boys lustily waving Italian flags on top, and Mama (who said there were no mothers-in-law in ballet?) accompanying them. Nevertheless, what was left was enough to make even the most cynical of spectators admit that life was worth living.

First there's a pas de six that opens with a lyrical passage for four women and two men. They manage to partner off in a series of patterns that is always logical, never contrived. Meanwhile the mood of their dancing conveys the fondness the participants have for one another and, indeed, for every other dweller in their village, all of whom seem to know each other by name as well as predilections. Then this band encounters a seventh, the man who gets to do the first of seven solos, launching fireworks of an understated prowess that define the Danish dancing spirit.

There are seven solos in all--each as inventive as it is demanding, each spilling forth fascinating and incredibly deft combinations of steps and posture: soaring leaps with one leg curved behind as in the famous statue of Mercury, arms outstretched as if to embrace the onlookers; buoyant jumps in place that are studded with beats, the arms now lowered and quiet; gentle side-to-side shifts suggesting reeds blown by a breeze this way and that; and witty reversals of direction that, no matter how often you see them, always register as a surprise.

It's Easy When You Know How: Alexander Stæger, members of the Royal Danish Ballet, and students in the company's school in Act III of Bournonville's Napoli

Photo: Costin Radu

Everything is executed, of course, as if it were child's play. The solos are interspersed with the dancing of a linked trio of young women who seem to rank between the soloists and the happy crowd of neighbors cheering them on. (Tambourines play a big role here). The community is jubilant because the lovers' story, a fraught one, has miraculously ended in joy, and the audience in the theater finds the mood contagious. The excitement intensifies with an exuberant tarantella and finishes with a communal dance invoking the gods of fertility, as is only appropriate to the occasion.

All the while, on a bridge in the background, there's a bevy of children clapping in time to the music's changing meters, gleefully raining confetti down on their elders, and, I'm told, memorizing the solos so that they can perform them when their day comes. Towards the end, some ten of these children--here, the Danish ones, the others being borrowed locals--descend from their perch to skip neatly in pairs through the ranks of their elders. Few onlookers can remain unmoved.

The New York engagement ended with four performances of La Sylphide, the sole Bournonville ballet with a long history in the international repertoire. I went to the last one for sentiment's sake, because it was the last, and to another that I chose for its casting: Gudrun Bojesen in the title role and Sorella Englund as the witch, Madge, an interpretation that I've never seen equaled in the years I've been looking at dance.

Bojesen, the RDB's finest example of classical dancing in the Bournonville style, is, quite simply, the most exquisite Sylphide I've ever seen. Enchanting in the contemporary context--as an enticing but impossible vision--she also evokes yesteryear's Sylphides, whom we know from etchings and photographs dating all the way back to the 1830s, when the choreographer created his version of the ballet, co-opted from the French one and presumably "translated" somewhat to reflect Danish values.

A Danish Ideal: Gudrun Bojesen in the title role of Bournonville's La Sylphide

Photo: : Martin Mydtskov Rønne

The first thing you notice about Bojesen is her radiance, coupled with the fact that the glow seems to be inextinguishable and to come from within. Yes, such a quality is intangible, but it counts nonetheless; I'd go so far as to argue that no ballerina can be considered significant without it.

Of course technical accomplishment can be discussed more concretely. Take, for example, the extraordinary softness of Bojesen's footwork. She wears the lightest and most pliant of pointe shoes, which allow her enormous flexibility. And when she moves, even descending from air to earth in a leap or jump, not a single footfall can be heard. This achievement is essentially nonexistent today; in Bojesen's case, it furthers the illusion that the Sylphide is wrapped in an aura of silence, apart from music.

Bojesen duplicates the virtues of her footwork in the suppleness of her entire body as she moves through space, thistledown style. What's more, her mimed gestures are woven into her dancing so that the barrier between poetry and prose miraculously dissolves. She plays the Sylphide, rightly, as amoral, a creature of nature, driven by her own desires, and utterly poignant in her death, which results from her loving a mortal man.

Poor James, this creature he's dreamt of--perhaps created in his imagination--lures him away from a humdrum if safe existence. He's slated to marry and find contentment with the life laid out for him by family and friends. But how can he resist the Sylphide's allure? It's a call to freedom from constraint, to an existence in which nothing is preordained, a call to bliss.

Over the years I've seen Englund play Madge several times; on each occasion, she had imagined the character anew. In her single New York appearance in the role she seemed to be a faded beauty with piercing eyes who had fallen on hard times or, like the Sylphide, an otherworldly creature, the sort whose presence we may sense through fleeting glimpses or simply by intuition. Perhaps, Englund may be suggesting, she is a sylphide who has fallen from grace.

Englund makes Madge's motives complex (as they are in novels and real life, but rarely in ballet). The witch craves revenge on James who so feared her presence, warming her frail, chilled body at his fireside, that he threw her out of his house; at the same time she lusts to have him for herself. Once she has duped James into destroying the Sylphide, capturing her with a poisoned scarf, and he lies swooning (perhaps dying) at the her feet, she forces him to look up and see his unseizable beloved being floated into the heavens. But no sooner does Madge gloat over her victory than she's dismayed by what she's lost through her jealousy and then, finally--the curtain line is hers--triumphant in her power. Englund conveys all this with an energy and focus remarkable in both their physical and psychological dimensions. Susceptible viewers, and I'm one, are duly shaken.

Ulrik Birkkjær offered a decent James, admirable for the correctness of his dancing, but he was no equal to the two transcendent women in the cast or to my memory of Nikolaj Hübbe's playing James to Englund's witch some years ago. That was a blazing encounter of two supremely gifted artists exploring the primal subjects of love, wrath, and power. The possibility of witnessing performances like that, rare though they are, is what keeps me going to the theater.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

and, from the archives:

On the premiere of Nikolaj Hübbe's production of La Sylphide: The Danes at Home, Seeing Things, September 26, 2003

On the Bournonville Classes: Total Immersion: The Bournonville Festival, No. 8, Seeing Things, June 11, 2005

School of American Ballet: 2011 Workshop Performances / Peter Jay Sharp Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / June 4 and 7, 2011

As classical dance fans know, the annual Workshop Performances of the School of American Ballet--New York City Ballet's renowned academy--display the accomplishments of its budding teen-age dancers, some of whom will be the next decade's stars, others who will make a corps de ballet ever more deserving of its name--"the body of the ballet."

This year's performances--I saw two of the three showings, the matinee and evening performances on June 4--can be considered a landmark event. The two casts of nine men (average age 17 ½) alternating in Peter Martins's 1987 Les Gentilhommes proved irrefutably that, after decades of working toward the social acceptance of boys who choose to dance, America, with SAB in the lead, can produce a male contingent of classical dancers of the highest caliber.

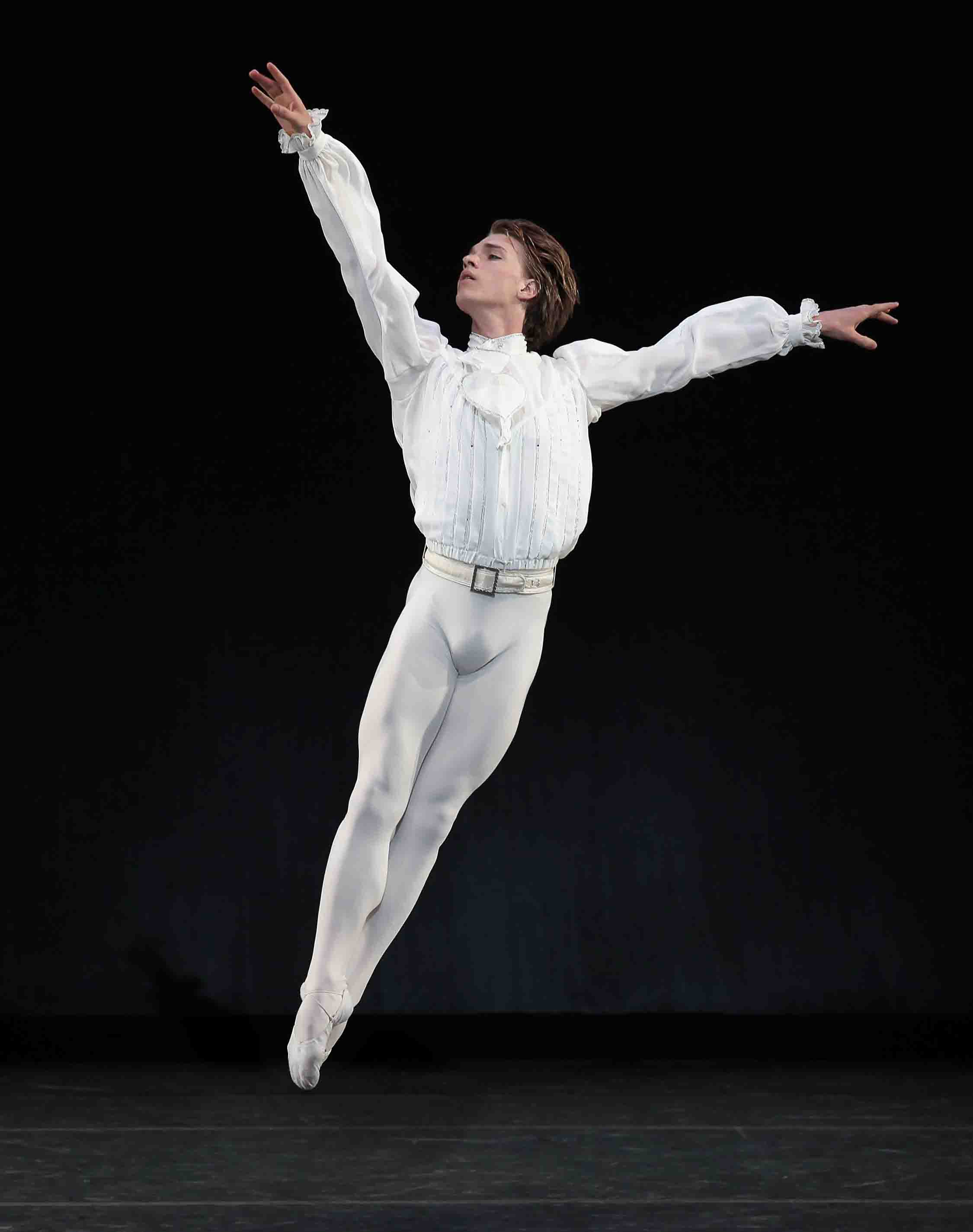

Amazing Grace: School of American Ballet's Harrison Ball in Peter Martins's Les Gentilhommes

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Set to felicitous music by Handel, Les Gentilhommes demonstrates the refinement a young man can achieve through rigorous schooling in strength, exactitude, selflessness, and unforced grace of manner. The ballet's cast of nine is dressed in loosely pleated white shirts, ruffle-trimmed at the wrist and neck, and unforgiving white tights. They might have stepped out of Castiglioni's Book of the Courtier, which describes the attributes a young man of the Renaissance needed to cultivate in order to shine in courtly society.

The breathtaking adagio in place with which the ballet opens consists solely of changes in posture and gesture, so the viewer can see the harmony of each dancer's form from shifting points, as if she or he were slowly walking around a piece of sculpture.

Then one of the nine, placed at the center of the group, acts as its leader, proposing a brief sequence of steps that is then reiterated by the others--in flawless unison. This consonance is never mechanical or show-offy (like the sensational Rockettes'). Rather, buoyed by music and breath, it looks perfectly--albeit ideally--human.

The piece progresses with three sequential trios, each emphasizing a specific aspect of classical-ballet virtuosity. Finally the nine dancers assemble again, now in a diagonal line, and take up their call-and-response activity, first in brisk tempo, then quieting into the legato pace of the opening. Gradually the stage darkens and they perform a révérence (the traditional formal bow of ballet students to their classroom teacher, with which they will eventually recognize and thank their audience).

The deference of the bows and the falling darkness seem to be reminders that a dancer's job is to serve his demanding art with humility, discipline, and devotion. Such a commitment eats up his youth and, because the body falters long before the desire to dance is quenched, lasts only halfway through his maturity. The reward is satisfaction in doing what one was destined to do--and, just possibly, glory.

Ad Astra Per Aspera: Young men from SAB--Joseph Gordon, center--in Martins's Les Gentilhommes

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Seeing Gentilhommes again at the evening performance, I noticed many lovely details:

● Proof that the angle of the wrist and the placement of the fingers can matter tremendously. (Once you learn this from dancing, you can look for it beyond dancing. In sculpture, in acting, in everyday life.) ● A movement traveling down a diagonal side-by-side line-up of the dancers almost faster than you could see each one execute it. ● Grands battements in which the leg is not forced or hauled upward but flung high softly and easily, even buoyantly. ● Each man's composed stillness when he's finished a phrase and is "just" standing in place. ● The reaching into the air with a single arm, the eyes following and extending that reach, and then, only then, the body soaring straight upward, almost invisibly thrust off the ground by the legs and feet. ● The beauty of the beats, tiny and unemphatic, added to a jump without the least effort, simply to make the jump glitter. (It's what the stars do to a nighttime sky.) ● Last, but most amazing, the men's perfectly turned-out fifth position: feet locked tightly together, right heel to left toes, right toes to left heel, forming a base so secure, a rocket could be launched from it. Peter Boal, one of the most impeccable principal dancers City Ballet ever harbored, a member of the original cast of Gentilhommes, now artistic director of Pacific Northwest Ballet, confessed one day with rueful humor to the SAB boys he was teaching, "I feel as if I've spent my life getting in and out of fifth position."

High Fidelity: SAB's gentlemen in fifth position

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Albert Evans and Arch Higgins, both former dancers with City Ballet, did the superb staging. Their production looked as if Stanley Williams--Evans's teacher, Higgins's teacher, Boal's teacher, Martins's teacher--had coached it himself. At the premiere of Les Gentilhommes in 1987, Martins dedicated the ballet to Williams with the words Skol, Stanley!, as if raising a glass to the justly renowned (and loved) classical dance pedagogue, a man with a persistent vision of exquisite simplicity.

George Balanchine said that his Allegro Brillante, which opened this year's Workshop program, "contains everything I knew about the classical ballet--in thirteen minutes." And it's an exigent 13 minutes for the leading couple--here Angelica Generosa partnered by Harrison Ball at the matinee and Joseph Gordon at the evening performance--as well as for the four necessarily highly accomplished couples who make up the ensemble. (At Workshop the ensemble was terrific and justly earned its own ovation.)

Co-stars: The ensemble of Balanchine's Allegro Brillante

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Balanchine's choreography to the single completed movement of Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 3 in E-flat major is exhilarating, often speed-driven and simultaneously insistent upon having its every image register with acute clarity. An abstract ballet, Allegro has no subtext whatsoever; it's about the sheer thrill of the academic vocabulary--and Balanchine's startling but eminently logical extensions of it--responding to the surging music.

As just one example, take the way the dancers' arms and legs keep thrusting sharply into diagonal positions one way and another, then quickly reverse, often taking the whole body in a new direction. Again and again, the dancer looks like a weather vane in a lashing tempest. Then take another--perhaps the ballerina's series of turns on pointe escalating into a string of every related turn in the book. Take yet another and you find your heartbeat has been accelerating all along the way.

Sparklers: Angelica Generosa and Joseph Gordon in Balanchine's Allegro Brillante

Photo: Paul Kolnik

My one problem with all this is that I simply couldn't take to Generosa, prodigy though she may be. Unlike most gifted pre-professionals, she's already a finished product, secure in everything she does (and tops with a pretty smile). She looks as if she's absorbed every bit of coaching she's been given and does to perfection everything she's been told to do. As a result, she has become an encyclopedia of scrupulously rendered feats. Now, if it's not already too late, she needs to become a dancer.

Admittedly, the leading woman of this ballet has got to be a virtuosa--the role was created for Maria Tallchief--but a 17-year-old virtuosa who doesn't seem to realize that there's a world beyond physical prowess kind of dampens your day.

The piece was staged by Suki Schorer, formerly a principal dancer with City Ballet, an instructor at SAB for four decades, and a longtime provider of distinguished Balanchine productions for Workshop. She must have realized that, given the senior SAB students at her disposal this season, Allegro couldn't have been staged effectively without Generosa, who danced all three performances.

Girl Crazy: Peter Walker, escorting Lindsay Turkel, one of his three dates, in Balanchine's Who Cares?

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Balanchine's Who Cares?, set to an irresistible slew of Gershwin songs, encourages belief in the choreographer's assertion that "ballet is woman." Susan Pilarre--like Schorer, an expert stager of Balanchine's ballets--mounted the piece for Workshop with remarkable insight, but it was clear that she didn't have enough women to fill the ballet's requirements--or her own. Each of the female soloists, at the very least, must have excellent technique and, most significant, her unique "perfume"--if the ballet is to evoke the many moods of romance proposed by the songs and the choreography. Each should have the power to make you fall in love with love. But as past Workshops have demonstrated, there are vintage years in dancers as well as in wines, and this year's crop had few women of that special quality.

Man About Town: Walker in Who Cares?

Photo: Paul Kolnik

It was left to the leading man to carry the show. He has a duet with each of the three main women, followed by a solo of his own. Peter Walker was fast and fleet in the role, always attentive to the lady in his arms--indeed he had no eyes for anyone but the one of the three he was dancing with at the moment. (This alone was bound to make viewers a little suspicious. Had Walker decided he was playing a trickster?) He went on to perform his solo with the casual ease of Jacques d'Amboise, who originated the part, but added to that a hint of cunning and danger. It suited the portrait of a young man about town who seems sweet and sincere enough but perhaps is not quite the gentleman he's billed as being--or that Walker had appeared to be, not an hour before, in Les Gentilhommes.

A male quintet, to Bidin' My Time, offered viewers another look at performers who'd caught their eye earlier in the program. I was particularly happy to see Austin Bachman, whose promise and progress I've followed for a couple of years. He still looks boyish and is more than ever a model of classical correctness--presented softly, as are his modesty and charm.

I was delighted, too, to notice Silas Farley--tall, willowy, and gentle--for the first time. He's the sort of dancer who makes you imagine the ballets that might suit him, even though, so far, you've only seen him in one or two.

Follow the Leader: Jock Soto as the Ringmaster parading 48 girls from SAB in Jerome Robbins's Circus Polka

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The school's Children's Division, represented by Circus Polka, looked better than ever this year. Every time I see this three-minute showpiece, devised in 1972 by Jerome Robbins for 48 girls--ranging from tiny enough to be (wrongly) dismissed as "cute" to just pubescent middle schoolers--the pony tails are longer and bouncier; the uniformly slender legs, molded by ballet training, more lithe and disciplined; the footwork more finely articulated; the stage presence more confident and joyous.

There's an anecdote attached to the piece that's recalled whenever the ballet is performed. Back in 1941 the Ringling Brothers, Barnum & Bailey Circus invited Balanchine to choreograph a routine for some 50 elephants and the pretty girls who rode them. Accepting the challenge, Balanchine asked Stravinsky (who, along with Tchaikovsky, was a source of unending inspiration for him) to compose a brief score--a polka perhaps--for the occasion. After being assured that the elephants were "very young," the composer complied and, in 1942, the show went on. The score bore this dedication: "For a Young Elephant." Three decades later, for City Ballet's Stravinsky Festival, Robbins co-opted the music for three tiers of SAB girls and an adult Ringmaster who put them through their paces.

Spelling Bee: For the curtain line of Robbins's Circus Polka, the young dancers form the initials of Igor Stravinsky, who composed the ballet's score

Photo: Paul Kolnik

This year's Ringmaster was Jock Soto, a former City Ballet principal dancer, now a member of SAB's faculty. The piece was staged by Garielle Whittle, a longtime member of the faculty as well as children's ballet master for the company. The Ringmaster wields a mean whip (which of course never touches a child). Unarmed, Whittle prepares youngsters to combine exorbitant energy and technical precision with springtime freshness and grace.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary