Seeing Things: May 2011 Archives

American Ballet Theatre: Ratmansky, Wheeldon, Millepied, and Tudor / Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / May 24-26, 2011

The lone mixed-repertory program in American Ballet Theatre's eight-week spring season at the Metropolitan Opera House attempted to lure today's audience, addicted to multi-act story ballets, to a more varied--and riskier--scenario. It offered new pieces by the two most gratifying classical choreographers in our midst (Alexei Ratmansky and Christopher Wheeldon), another by the fellow most avid to join their ranks (Benjamin Millepied), and the revival of a work by a past master (Antony Tudor), though not of one of his masterworks.

Antony Tudor (1908 - 1987)

Photo: Elizabeth Sawyer

In Dumbarton, set to Stravinsky's neo-classical Concerto in E-flat (Dumbarton Oaks), Ratmansky devotes himself to one of his specialties--making an ensemble fascinating in itself. The choreography offers a perpetuum mobile opportunity to ten dancers, who are also seen, at intervals, as separate couples. (Imagine a video camera zooming in on a particular pair in a community to reveal more and more about them.) The full-group patterns look like quick-shifting kaleidoscope images that have been released from their customary geometric boundaries. Ratmansky's flair guarantees that the unleashed, unexpected patterns never once lose their coherence.

Nearly four decades before Ratmansky created his piece, Jerome Robbins used the music for his Dumbarton Oaks, choreographed for the New York City Ballet's 1972 Stravinsky Festival. Seasoned viewers remember that ballet, if at all, as a feeble effort, having something to do with recreational tennis, with the costumes vaguely reflecting the chic Twenties. Now the score--like so many things in life--has been given another chance. This dance-historical footnote would be irrelevant if there weren't hints of Robbins's predilections in Ratmansky's ballet--not in the steps and style, but rather in its evocation of an appealing past time and place. In Ratmansky the idyll is simpler and sweeter than contemporary urban life. Richard Hudson's costumes--with their all-cotton look--suggest ordinary folk living good lives far from big cities. Without the least bit of sentimentality or fakery, every one in this imagined realm looks young and beautiful.

And Then Suddenly, Without Warning: The full cast of Dumbarton, choreographed by American Ballet Theatre's Artist in Residence, Alexei Ratmansky

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

The tone of the choreography is largely playful, though when the music slows and grows quiet, Ratmansky lets the atmosphere of the dance become more meditative. Then, with almost no warning, one woman collapses in her partner's arms, falls to the floor, and is borne off, body supine and rigid, as if in a funeral procession. It made me remember being a fourth-grader returning to class from spring vacation and having the teacher announce to the room of 28 children and one empty seat fused to a cleared desk, that Charlie--stickball champ, ramshackle scholar, the kid with the irresistible grin--had died. Charlie? Die? How could this happen? He was only ten years old! Life's natural order had been hideously disturbed.

The music returns to an upbeat mode and Ratmansky, always prone to let joy have the victory over gloom, has the stricken woman return unharmed, unaffected by what has occurred a few moments earlier. It's the spectator who remembers.

Set to Benjamin Britten's Diversions for Piano and Orchestra, Wheeldon's sleek, handsome Thirteen Diversions shows the choreographer taking a step his audience has been hoping to see for quite a while. Like most of his work, the piece is exquisitely organized and inventive when it comes to steps, all the while adhering to classical principles and, for the most part, the classical vocabulary. But now, at long last, in a ballet that ambitiously has four principal couples sharing time and space with an ensemble of 16 (in itself no mean feat), Wheeldon has been able to access some emotion that actually looks genuine. It makes all the difference.

Typically, he reaches for design that is over-impressive. Brad Fields, credited with the lighting, has also created the décor: projections on the backcloth of huge fields of saturated color sliced by streaks of white light. The hues change with each of the thirteen passages. The eye is bombarded. I imagine that Jennifer Tipton, who has proved incontrovertibly that subtle lighting is the most persuasive, would be appalled.

Bob Crowley's costumes, too, are over the top. The principals wear white; the ensemble black. The theme is dinner-jacket tops for both genders (the men's have a 19th-century look, while the women's are feminized). Below, the men wear danseur noble white tights; the ladies sport knee-length fluffy skirts. The predominant fabric appears to be a lush, infinitely pliable satin, easily the most sensuous of materials. And have I mentioned the ballerinas' hair-dos? Very chi-chi. Must have cost a fortune.

Deep Song: Marcelo Gomes and Isabella Boylston in Christopher Wheeldon's Thirteen Diversions

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

Given the high style of all this eye candy, the dancers' demeanor is formal--until, in duets for two of the couples, myriad and mysterious forms of love surge to the surface. The emotions are not acted, though; they reside in the choreography. And the dancers, blessedly, make them happen, without distorting them with personal comment. Gillian Murphy and David Hallberg seem to enjoy an early-summer romance, the sort of thing where to abandon oneself to love is no big deal, but only natural, given the circumstances. Late in the ballet Wheeldon explores the other end of the amorous spectrum, giving the wonderful Isabella Boylston and Marcelo Gomes a gorgeous duet that is fraught with passion. It describes a bonding so deep and complicated that it hurts as often as it succors. In this pair of duets Wheeldon accesses a humanity he previously chose to ignore or needed to grow into. No artist is complete without it.

Troika, the Russian word for a carriage drawn by three horses, is used informally to refer to the passage in Balanchine's Apollo in which the exuberant young god gathers his three muses and drives them along at a brisk pace. It is also the name of Millepied's latest ballet, which is, in my opinion, the best work he has produced so far. Granted, this is not much of an endorsement, but it's a sign that, having spent a number of years learning his trade with uninspiring results, Millepied is now capable of constructing a ballet that is workmanlike instead of awkward, hollow, and/or baffling.

Troika, set to Bach cello music, gives us three guys of different heights--small, medium, and large, so to speak--although, strangely, nothing much is made of this in the choreography. Channeling Jerome Robbins in his Interplay mode, Millepied makes them best buddies, regular guys who are, you know, just hanging out, fooling around. Since the performers are not street kids but talents subjected to the long, arduous years of classical-dance training, it's hard to suspend your disbelief in the premise.

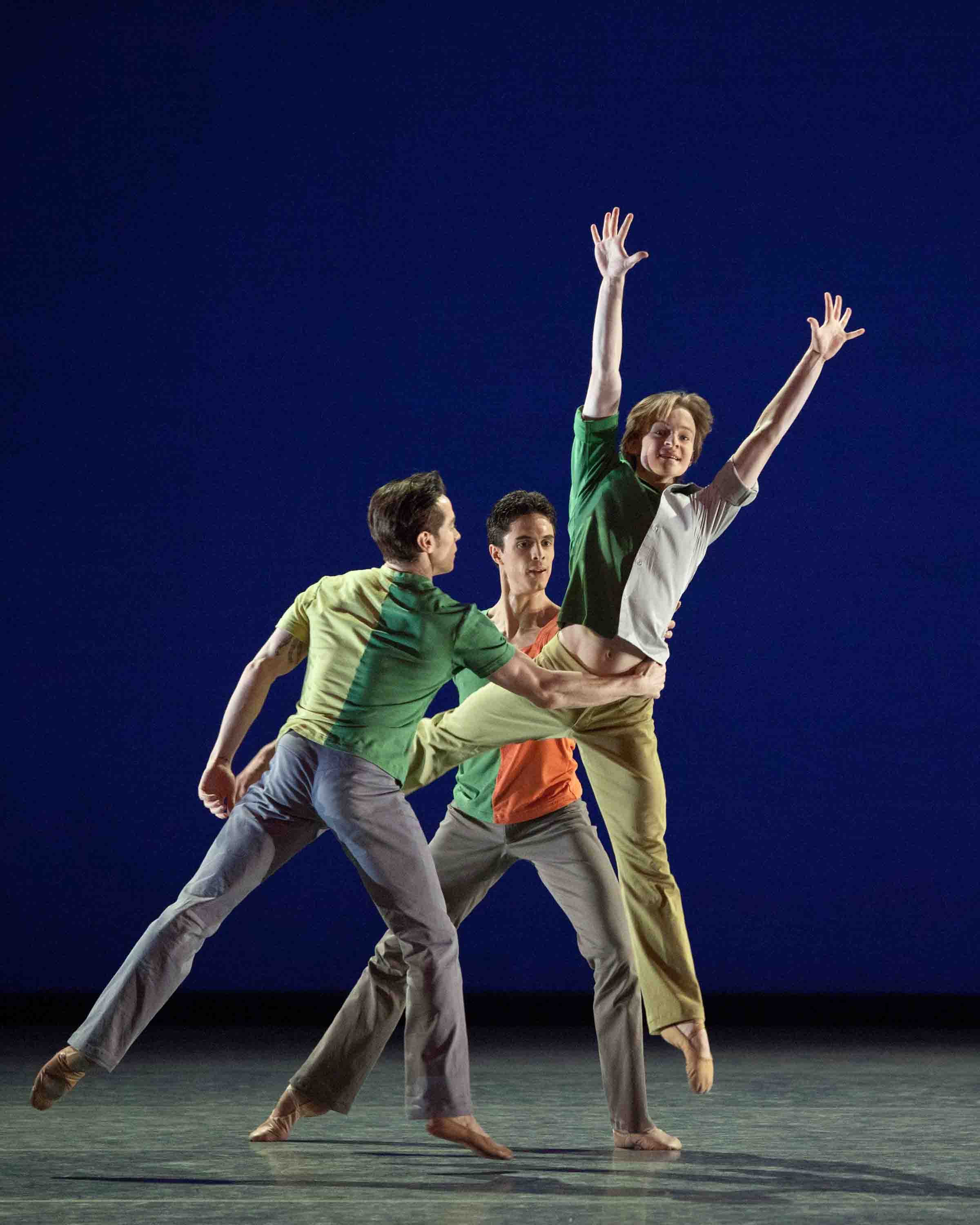

Boys Will Be Boys: Sascha Radetsky, Alexandre Hammoudi, and Daniil Simkin in Benjamin Millepied's Troika

Photo: Mikhail Logvinov

The fooling around is, inevitably, full of feats. They're acrobatic, jokey, show-offy, competitive without rancor--in other words, boyish--and no doubt intended to impress and charm the audience at the same time. Toward the end of the ballet, when even disarmed spectators may well have had enough and the "boys" are drenched in sweat, the tallest fellow leads a slow meditative section (a typical Robbins tactic for offsetting hijinks) in which we can assume the three are brooding over their inner feelings and perhaps their friendship too.

The dancers were swell. I preferred the first cast--Daniil Simkin (short), Sascha Radetsky (average), Alexandre Hammoudi (tall)--yet couldn't help feeling that these men were wasting their talents with a project short on authenticity. The cellist, Jonathan Spitz, who played onstage, was swell too.

What can I say about ABT's revival of Tudor's 1967 Shadowplay? The choreographer's small but utterly unique oeuvre, by turns tragic, tender, and acerbic, saw deep into the human soul, fusing gesture with feeling. When Mikhail Baryshnikov headed ABT, he called Tudor the company's "conscience." Tudor's ballets--among them Jardin aux Lilas (Lilac Garden), Dark Elegies, Pillar of Fire, and The Leaves Are Fading--have long been considered the company's legacy. But time has indeed gone by. Nowadays even the masterworks I've named fail to attract the general public, whose taste has been blunted by the large, the gaudy, and the next new thing.

It's possible that Shadowplay doesn't stand a chance. It has been considered a "difficult" piece from the moment of its creation--hard to understand and as much posture and gesture as full-fledged dancing. It's a mythical affair, reflecting Tudor's growing commitment to Buddhist thought and practice. It describes, all too vaguely, a young man's journey toward enlightenment as he encounters the denizens haunting his jungle home. The eerie music is Charles Koechlin's and relates to Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Book, which also informed Tudor's choreography.

The hero, called Boy with Matted Hair, is a human stripling, innocent and vulnerable, curious, too, but firm of purpose. He stays close to his meditation spot at the foot of an immensely gnarled tree with spidery branches as various forces arrive to tempt and torment him. There's a tribe of Arboreals, monkeys low on the spiritual totem pole; then the Aerials, six women in balletic versions of Cambodian dress; the Terrestrial, a gorgeous hunk of a man costumed like a Hindu god, who dominates the Boy sexually and belatedly receives his comeuppance; and the Celestials, two male bearers carrying a seductive woman high above the earth. She turns out to be a real harpy, hardly a desirable erotic companion. Presumably by force of will, the Boy overcomes these distractions to achieve Nirvana.

In the intermission a woman seated behind me, who had evidently seen me scribbling notes in the dark, asked me if I could explain the ballet we'd just watched. Before I could think, I blurted out, "No." For the sake of civility I quickly made amends, but I suspect my initial response was closer to the truth.

You can tell the ballet is considered "important" by the artists who've danced the leading role. Anthony Dowell, perhaps the most pure and touching male dancer in history, originated it. Baryshnikov took it on in ABT's 1975 revival. Herman Cornejo, who has an uncanny ability to grasp and then produce the style of any role he covers, was slated to portray the Boy in the current production but was waylaid by injury; Craig Salstein turned in a sensitive performance in his place--all tender-footed gait and unsullied soul--while Daniil Simkin appeared in the alternate cast.

Below, a glimpse of Anthony Dowell and Derek Rencher in the original production of Shadowplay by the Royal Ballet:

I hope the ballet remains in ABT's repertory long enough to give Cornejo his chance in it and to give me another chance to see what the music critic Andrew Porter saw in it: "If the 'content' of Shadowplay could be . . . verbalized," he wrote, "there would be no need for the ballet. Words can be only a crude pointer to the kind of work it is, a work in which Tudor, as ever, communicates in a clear, eloquent imagery, with great delicacy of nuance, what can be really experienced but hardly translated into any other medium."

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

American Ballet Theatre: Opening Night Gala / Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / May 16, 2011

Gala! Of course there were little speeches before the curtain--from Rachel Moore, American Ballet Theatre's Executive Director, resplendent in an origami-influenced emerald gown; Kevin McKenzie, the company's Artistic Director; and Carolyn Kennedy, whose girlish awkwardness has become part of her charm, following her mother's example of supporting the arts. Then a tasting menu of familiar love-story pas de deux for ABT's principal dancers and a pair of obligatory yet very well-deserved nods to the company's corps de ballet.

The ensemble assembled for a pair of all too brief excerpts that book-ended the program. These were drawn from the big-deal item of ABT's spring season at the Met, Alexei Ratmansky's The Bright Stream, to the score Shostakovich composed for a Soviet-era production. Ratmansky, who has just signed on for an extra decade as ABT's Artist in Residence, used the lively music but created new choreography to it in 2003--for the Bolshoi Ballet, during his tenure as head of that company. Two years later, the Russians presented the production in New York--to much delight.

Regrettably, the excerpts shown at the gala were so tiny (and the participants so many), that this preview did a disservice to the rollicking program-length work, which is set, as was the original version, on a collective farm. (In other words, not near a castle, a rural cottage, or a haunted lake.) First-time viewers must have been hard put to figure out from the excerpts what was going on. But I wouldn't for the world have missed the sight of Susan Jones--a diminutive woman of a certain age subject to embonpoint, former ABT dancer now an indispensable ballet mistress--turning incisive cartwheels in a billowing red dress.

Top Marks: Gillian Murphy in Balanchine's Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux

Photo: Jack Vartoogian

The most ravishing dancing of the evening was done by Gillian Murphy and David Hallberg, performing Balanchine's Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux. Consummate professionals, consummate classicists, and strong, clear technicians, the two gave a deliberate, almost solemn, rendition of choreography that was flawless in its polish.

This is obviously quite different from the tone Balanchine intended in 1960 when he made the piece for New York City Ballet. Back then it looked like a bagatelle tossed off by genius. Violette Verdy and Conrad Ludlow, the originators of their roles, danced it with great élan, as a playful romp full of verve and spontaneity. The piece was clearly made for Verdy's effervescence, her wit, and her unparalleled musicality. It was full of surprises, like the moment Verdy took off from one side of the stage and hurled herself, horizontally it seemed, over the huge gap that separated her from Ludlow, on the other side--and landed in his arms in fish-dive position. You'd hear the spectators gasp and laugh in delight, even before they thought to applaud.

But I liked the Murphy/Hallberg reading too, for its flowing, creamy dancing, for the way Murphy, in the slow-motion ending of the adagio, seemed to rise upward into Hallberg's embrace to arrive at a fish-dive position (the precursor of the one at the ballet's finish); and for the solos: Hallberg, always flawlessly placed, being gentle and buoyant; Murphy deft and animated in her allegro work; Hallberg riding the air in long leaps, then Murphy explicating Balanchine's disquisition on piqué turns and punctuating the coda with effervescent flying pas de chat. It's rare to find dancing you can call perfect.

Being Beauteous: Veronika Part and Marcelo Gomes in the grand pas de deux from Ratmansky's The Nutcracker

Photo: Geme Schiavone

Veronika Part has enraptured ABT fans in the way Sara Mearns has City Ballet's audience--through the irresistible appeal of a way of moving so luxuriant she reveals the very essence of dance. Not just academic classical ballet, which is simply her artistic language, but dance itself.

With the adept and empathic Marcelo Gomes as her partner, Part performed the grand pas the deux from the Nutcracker that Alexei Ratmansky created for ABT last year. Through a few of the missteps and hesitations she's prone to, she made it evident that she wasn't likely ever to achieve the cool perfection that Murphy and Hallberg had just demonstrated--and that it doesn't matter.

In this performance Part was at her most tender, like a child on Christmas morning, awakening to joy, or an adolescent awakening to romantic love. Individual steps and phrases flowed into each other like speech transmuted into song. Remarkable lifts were executed not bravura-style, but as part of the pair's characterizations. In the ballet, Part's role embodies the child heroine's idyllic dream of what she might become and experience as a young woman. Dancing this role, Part makes you believe that the dream--absurdly simple, sweet, and innocent--might actually come true, even if you've already grown up.

¡Sí Cuba!: Jose Manuel Carreño (second from right) and friends in Georges Garcia's Majisimo

Photo: Gene Schiavone

An all-star, no-star octet of Hispanic dancers, seven of them born and trained in Cuba, danced Majisimo, choreographed by Georges Garcia in 1965 for Alicia Alonso's Ballet Nacional de Cuba. Set to music from Massenet's Le Cid, the piece is structurally naive, but it made its point: American dance has been conspicuously enriched by Cuban artists, who typically mate technical acumen with human warmth. The cast: From ABT, Jose Manuel Carreño, Paloma Herrera, and Xiomara Reyes; from San Francisco Ballet, Lorena Feijóo and Joan Boada; from Boston Ballet, Lorna Feijóo and Nelson Madrigal; and Reyneris Reyes from Miami City Ballet.

Carreño, surely the best beloved of ABT's dancers, could be the poster boy for the appealing "Cuban style." Here, apart from a brief solo moment, rather than performing as a star, he played a modest--and endearing--role as a member of a congenial team. He will appear in his more familiar guise--prince of the proceedings--at his farewell performance on July 30. He'll be Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake, partnering not one, but two of his fortunate ballerinas, Julie Kent and Gillian Murphy, as Odette and Odile respectively. Be there, prepared to cheer and weep.

Sweet Sixteen: Alina Cojocaru in the Rose Adagio from The Sleeping Beauty

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Wearing incredibly soft pointe shoes, properly shy and girlish, the petite Alina Cojocaru, a guest from the Royal Ballet, performed the Rose Adagio from The Sleeping Beauty, abetted by four local princely cavaliers. Ripped out of the context that would identify her as the 16-year-old Aurora, heiress-apparent to a fairy-tale throne, being introduced to the quartet of regal suitors from which she's expected to choose a mate, this celebrated pas de cinq made a mere gymnastic thrill of its climax. The four balances in unsupported attitude that Margot Fonteyn famously prolonged when the Royal Ballet made its American debut at the old Met started a tradition. Here's Dame Margot upholding her own tradition.

Cojocaru handled the technical challenge credibly, though not incredibly. (Her forte is not technical dazzle but, rather, lyricism, musicality, and sensibility.) Still, she managed to hold one balance long enough to suggest a soap bubble suspended in the air and finished with a flourish, thrusting her free leg straight behind her with such a rush of energy, it seemed to blaze like the tail of a comet. She made all the doings musical and even snuck in some subtle acting--revealing a growing emotional confidence in her relationship to the suitors, even a flicker of flirtation, despite the fact that Aurora is even more of an innocent than the Juliet who hasn't yet set eyes on Romeo.

Dangerous Liaisons: Diana Vishneva and Marcelo Gomes in MacMillan's Manon

Photo: MIRA

In contrast to Aurora, the Manon of Kenneth MacMillan's eponymous ballet has no virginal impulses whatsoever. Au contraire. Diana Vishneva, a principal with the Mariinsky Ballet and ABT as well, and the marvelous Gomes gave a potent rendering of what you might call a first-lust pas de deux. They made every one of the choreographer's impossible lifts, meant to be equivalents of physical passion, look credible, even beautiful. (When they don't come off, as happens with lesser dancers, all you can see is the shame and danger the exploits impose on the performer--the slipping, the groping, the fear, if you will, of falling.) At the gala, all went well.

I wish I believed more in Vishneva's characterizations. Although they're unquestionably multifaceted and intelligent, they seem to be constructed, not charged with actual feeling. They're so logically conceived and so well performed, physically and theatrically, surely it would be easier to surrender to them, to accept the beauties of what this fine dancer can do without dwelling too much on what will never be. I'm just not there yet.

There was more, much more: The Act II ("White Swan") pas de deux from Swan Lake, danced by the promising Alexandre Hammoudi and the ever-more-capable yet still soulless Paloma Herrera; Jessica Lang's ridiculous Splendid Isolation III, in which Irina Dvorovenko and Maxim Beloserkovsky were upstaged by yards of cloth; the Act III ("Black Swan") pas de deux from Lake, in which Michele Wiles, whose career has unfolded as a journey from no drama to melodrama, was partnered by Cory Stearns, who was coping as well as he could; and the Act II duet from John Neumeier's Lady of the Camellias, in which Julie Kent played an appealingly wan Marguerite to Stearns's Armand. Perhaps the "small plates" scheme, so popular with diners-out, is no longer the best model for a ballet gala.

Pre-professional students from ABT's Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School looked quite accomplished--I'd recommend only greater sharpness of attack--in Raymond Lukens's Karelia March, set to music by Sibelius. The most gifted, persevering, and luckiest among them will go on to ABT II and then to the parent company. Their path is challenging and its results uncertain. Put this list of their names in the bottom of a desk drawer and look at it five years from now: Kimberly Buesser, Amanda De Oliveira, Ellie Greenhouse, Gabrielle Johnson, Seika Paradeis, Brianna Steinfeldt, Alison Stroming, Cassandra Trenary, Paulina Waski, Fernando Duarte, Beau Fisher, Max Isaacson, Shu Kinouchi, Lucius Kirst, Alex Kramer, Connor Redpath.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / May 3 - June 12, 2011

The Women in White: Members of the New York City Ballet corps de ballet in George Balanchine's Symphony in Three Movements

Photo: Paul Kolnik

New York City Ballet opened its spring season with a week and a day of programs devoted solely to the abstract Balanchine ballets that form the core of the master's repertoire and aesthetic. Balanchine worshippers, often discouraged by the works acquired since the master's death, flocked to the performances, breathing sighs of gratitude.

The irony of this mini-festival was that Balanchine himself would never have offered such homogeneous programs. An accomplished chef, the choreographer liked to take his metaphors from the culinary art. He'd point out that a satisfying evening of ballets would provide contrasting elements, just as a good dinner furnished varied courses: aperitif, main dish, and dessert.

Even so, I saw all the ballets on offer, some of them twice. I didn't mind the programming at all. Granted, being a dance critic, I'm in the trade, so to speak. And from the moment I saw Balanchine's ballets, danced by City Ballet--at my second dance performance ever, early in my teens--I felt that this choreography was my heart's home.

What made me think that "Balanchine: Black & White," the May 3-8 mini-festival of the choreographer's "leotard ballets"--as they're called because their costuming is only a subtle step away from practice clothes--would bring the productions back to what they once were? Only a viewer's nostalgia and longing, I assumed--nothing rational.

After all, aficionados have been carping for close to three decades about changes in the original choreography that have crept in--probably from sheer carelessness. The preservation of the ballets as Balanchine left them has often seemed lax, precious rehearsal time being given to one new work after another that's unworthy of it. As for intentional changes, the general opinion is that Balanchine himself had the right to retool his work and often did (Think of the many versions of Serenade a long-time fan has seen! Think of the ruthless cropping of Apollo!), but that the cut-off for second thoughts should be 1983. I agree almost wholeheartedly.

As for the style in which the Balanchine ballets have been performed for some time, for the most part, they've been danced as the rest of the repertoire is now danced: coolly, sleekly, sometimes dazzlingly, but without fervor and without subtext. City Ballet's dancing is definitely sharper, more physically thrilling than it was in the old days; veteran observers complain that it's all surface. This, I suspect, is a reflection of today's culture; if so, there's nothing much to be done about that. Yes, coaching from dancers who were shaped by Balanchine himself could offer a corrective. I've seen Violette Verdy, Suki Schorer, and Merrill Ashley work marvels with their skill. But under Peter Martins's long reign as Ballet Master in Chief, this practice has not been much encouraged.

Balancing Act: Teresa Reichlen, partnered by Amar Ramasar and Craig Hall in Balanchine's Agon

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Nevertheless, after a rather lackluster first night--protracted and stormy contract negotiations had been settled only that morning--the "Black & White" project produced a little miracle: Balanchine revivified. The dancers and their ballet masters seemed to have looked closely at the choreography that is their heritage--and their responsibility--and decided it was worth heightened attention and heightened effort. The ballets seem to have been carefully examined and scrupulously rehearsed. Not a single one coasted along on the principle of business as usual. Several of them positively gleamed with the artists' discovery of the choreography's richness and wisdom.

The audience noticed. Judging from its fervent applause for choreography of such absolute purity that it is customarily given a polite but tepid response (Monumentum pro Gesualdo, for instance), the public was suddenly charged with enthusiasm. It had discovered that Balanchine's most subtle, complex, and rigorous ballets were like nothing else on earth. Which is true enough.

The lesson the City Ballet's administration might do well to take from one of the grandest weeks of dancing that I, for one, have ever witnessed, is that Balanchine's day isn't "over" or his work impossible to restore to its original glory. The ballets simply require focused and continuing attention. Providing this is an issue of time and money, which the company needs to budget in proportions somewhat different from the ones that have prevailed for too long. Less, I'd urge, for those gimcrack festivals of new work that yield almost nothing worth keeping; less for choreographers borrowed from Broadway who, after all, fail to entertain; less for choreographers who are "all the rage." More for Mr. B.

Social Perfection: Maria Kowroski and Charles Askegard, center, in Balanchine's Monumentum pro Gesualdo

Photo: Paul Kolnik

"Balanchine: Black & White" presented a dozen ballets. They were: Apollo (1928; music: Stravinsky); Concerto Barocco (1941; Bach); The Four Temperaments (1946; Hindemith); Agon (1957; Stravinsky); Square Dance (1957; Corelli and Vivaldi); Episodes (1959; Webern); Monumentum pro Gesualdo (1960; Stravinsky); Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1963: Stravinsky); Duo Concertant (1972; Stravinsky); Stravinsky Violin Concerto (1972); Symphony in Three Movements (1972; Stravinsky); Le Tombeau de Couperin (1975; Ravel).

The works that made the most overwhelming impact on me were Episodes and Symphony in Three Movements. Episodes, whose Webern score fractures the world, coolly and mercilessly anatomizes it, and then, at the very last moment, makes it cohere again, opened the second night of "Balanchine: Black & White" and struck me dumb. I had admired Balanchine's response to--dare I say extension of?--the music since the ballet's premiere, for a starkness and strangeness that described the universe as it really was, once you quit resisting the truth.

From the start, it seemed to me one of the most forward-looking ballets I'd ever seen (or would be likely to see). I was fascinated by its spare and seemingly arbitrary movement, by the fact that stillness (in the music and in the motion) was a major player in the proceedings, and by Balanchine's fearless answer to the question What if you removed all the rules, or, if you will, the conventions of choreography? I was even delighted by the fact that, at the end of a musical segment, the dancers simply stopped, then walked--almost like pedestrians--to the spot where they would take up again when the music resumed.

Last week, still remembering the pleasures provided by the original cast--the pioneers of Episodes, as I think of those dancers--I saw the perfect polished version of the ballet, meticulous in every respect. The time in which it is set still seems to be the future, while the principles guiding the choreography are in no way estranged from classicism.

For almost four decades, Symphony in Three Movements has represented the thrill and terror of exorbitant energy as well as the strangely inverted results that occur when that force is played out. Just now, it could serve as a parable of our time, in which individuals, communities, and whole societies disintegrate, besieged by an overload of information and the simultaneous failure of authentic communication--or, simply, succumbing to the all too human impulse toward conflict and violence.

The ballet's tribe of formidably svelte, long-legged women in skin-tight white leotards, posed in a diagonal line from one corner of the stage to another is one of the most compelling opening images ballet has to offer. Balanchine gives you just a few seconds to take it in, and then has these women, whose type he has essentially invented, prance into motion with irrepressible energy, ponytails flying and whipping. When that line reforms at the close of the first movement and creates the optical illusion of a current (of a surging river? of electricity?) swirling along its path as, fluidly, one after one, the women turn to shift the direction in which they're facing-well, you know you're not in Kansas anymore.

In between those two moments Balanchine shows us the rest of the world: five women in black, perturbers of calm, often in a coiled-to-spring position, abetted by male partners, and three leading women whose leotards (and hair ornaments!) are in three just slightly, and deliberately disconcerting, incompatible shades of red. They are also accompanied by partners and may represent humanity.

In the third movement the full cast is deployed on an invisible grid, sometimes becoming the grid itself, by means of line-ups and arms stiffly outstretched to the side. The dancers might be soldiers or prisoners; either or both, it's up to you and your own fancy (as is, needless to say, everything in my own "interpretation" of this ballet). The women in white, stationed on the border line between the stage and the wings, move into and out of concealment gesturing with their arms in a code no one can crack. (Whom you can see and when you can see her depends on where you sit. This is not simply a given observation of art you look at, but a useful lesson in life.)

Finally the male contingent moves forward and, laid out as if on graph paper, stretches full length on the floor in push-up position, heads toward the audience, poised for action, like patriots futilely declaring, like so many that went before them, "We're ready." Ready for what? Annihilation?

The middle section of the ballet is an eerie duet for one of the three leading ladies and her partner (I saw Janie Taylor and Jared Angle) in the roles originated by Sara Leland and Bart Cook.) You might think that, as is customary in classical-ballet duets, they've come together in privacy to explore--or make--love. In the world Balanchine has envisioned with this piece, there's no such thing as love; it's been blotted out by circumstances. Their exchange is one of bodies reduced to stylized movement colored by, perhaps, Balinese (that is, "foreign") dancing, and it ends with the partners significantly leaving the stage in opposite directions, rather than any hint of bonding.

One of the best things about Symphony in Three Movements, I hasten to add, is the tremendous impression it makes even on those who join with Balanchine's own (at least public) stance against interpretation.

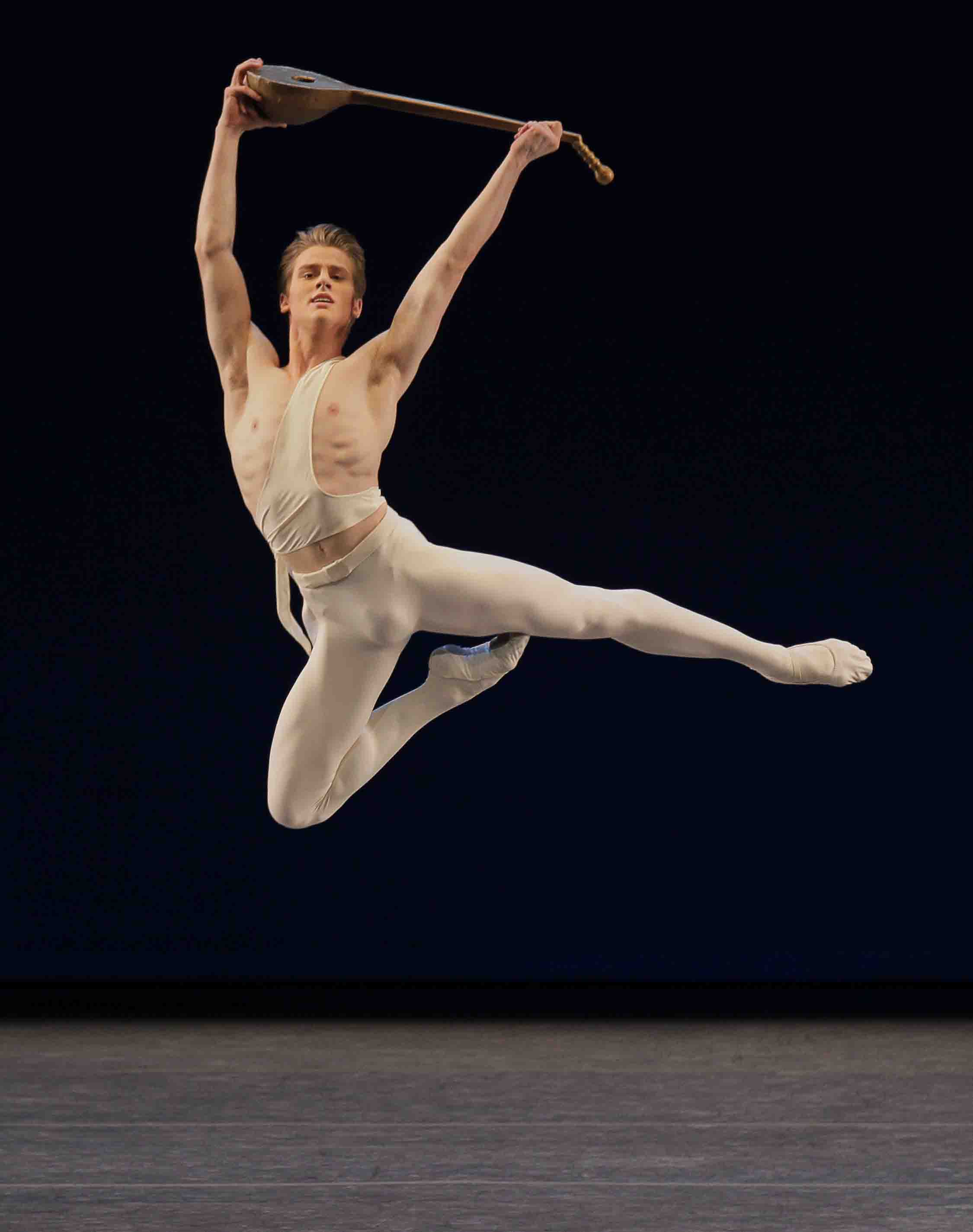

Young God: Chase Finlay in Balanchine's Apollo

Photo: Paul Kolnik

As for the dancers seen in principal roles in the course of the "Black & White" project, two men in the rising generation stood out particularly. First among them was Chase Finlay, who joined the corps de ballet in 2009. With his thick blond hair and expressive mouth, he can look like a pouting Cupid and is surely a candidate ripe to rival Justin Bieber as a darling of the screaming tweens. Fortunately he has better things to do, given his prodigious technique and his ability to possess the stage with the aplomb of a seasoned star.

Entrusted with the lead in Apollo, Finlay renewed the vitality of this pivotal ballet, Balanchine's first masterwork. Clearly he was using everything he had been told or read about the role, and his boss, Peter Martins, had been one of its most memorable interpreters. Still, Finlay made it spontaneous and his own. Perhaps he identified with his character: a very young man learning the job of being a Greek god.

At moments in Apollo, Finlay recalled the young Baryshnikov, not merely in looks, but so on top of the challenges in the choreography, he could lend an impish touch to the playful passages with his troika of muses. In Duo Concertant, he was remarkable again, impersonating an ordinary fellow, one your daughter might be dating (assuming they were both into classical music). Here he partnered Megan Fairchild, who, though technically adept, falls all too easily into the trap of cloying sweetness. Finlay's presence brought fresh air to the ballet (which has an admittedly hokey premise) and to his ballerina.

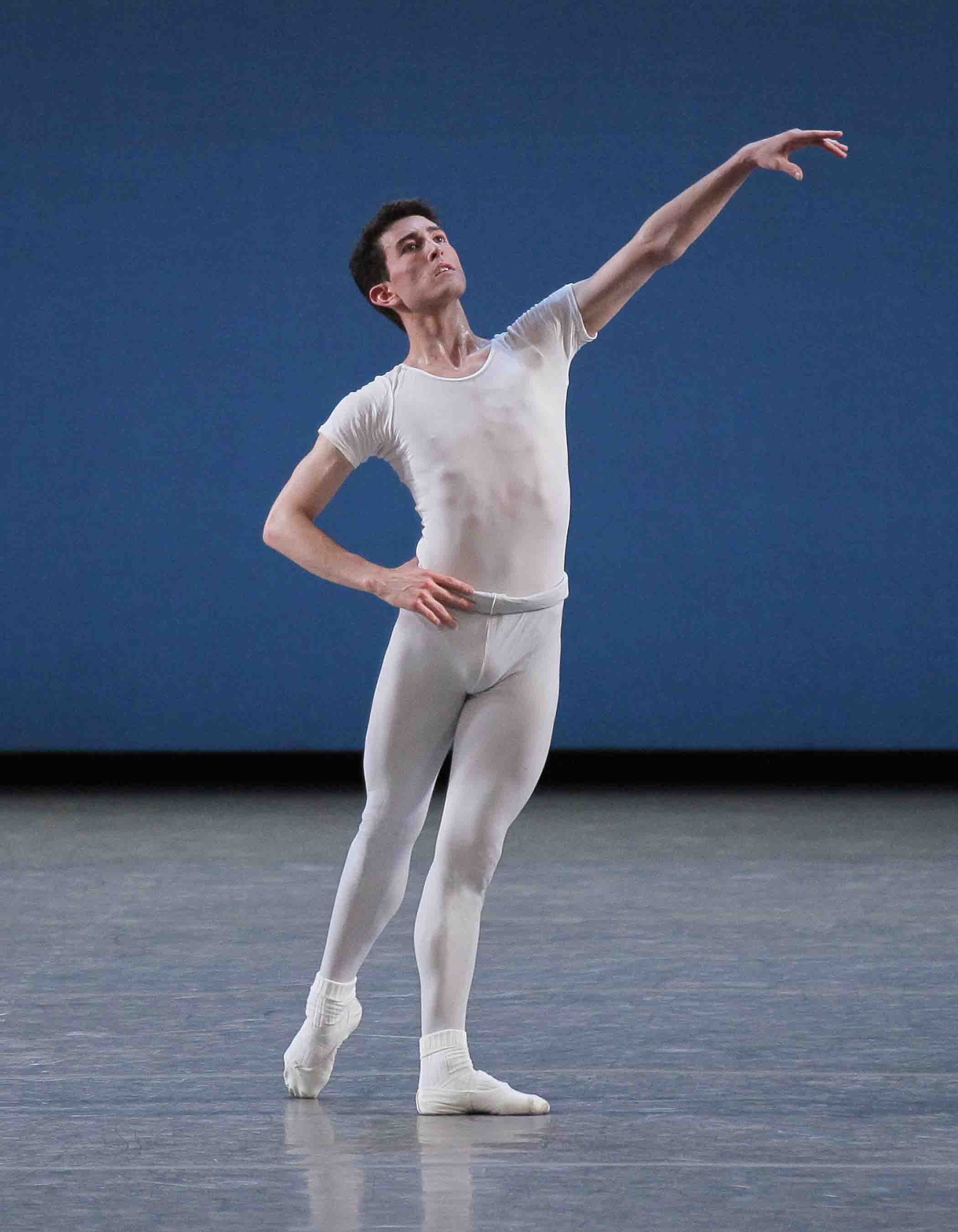

A Princely Meditation: Anthony Huxley in Balanchine's Square Dance

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Nowhere near as sophisticated in stage presence as Finlay, Anthony Huxley, a corps member since 2007, is nearly his equal in promise for the future. Dancing the male lead in Square Dance, the opening ballet in the "Black & White" series, he was a wonder--from his compact, beautifully proportioned body to his flawless coordination. He seems to be airborne by nature, not through effort or training. He's not so much a high-flyer, though, as forever buoyant.

He has dark, close-cropped hair and a somber, innocent face, like that of a thoughtful child. There's nothing in the least pushy about him, no Mr. Bravura here, just dancing that's at once a plain, quiet statement and irrefutable proof that classicism still counts. He makes every one of the old steps look newly minted.

In the celebrated male solo that Balanchine made belatedly--to fill the plea of the cast's women for a breather after the extra-frisky section they called "Chase the Rabbit," Huxley already vies with the finest of his predecessors, Bart Cook and Peter Boal. From the moment he appears on the otherwise empty stage, he's surrounded by an air of mystery, aloneness, and singularity. He might be the prince of a lost kingdom. As he proceeds through a chain of small phrases, made more of posture and gesture than the heat and flow of ordinary dancing, he evokes a mood of remembering and longing for a state he once inhabited, but which has disappeared, leaving him only dignity and resignation.

Caught: Maria Kowroski (airborne) in Balanchine's Monumentum pro Gesualdo (alternating in the role with Teresa Reichlen)

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Among the women, the most evocative performances were given by principals whom I've admired for some time now. Teresa Reichlen, the long-legged epitome of poise, was exquisite in Monumentum, her pale face grave, her movement sublimely calm and clear, her hands making filigreed gestures. She made me think of a medieval princess--perhaps the one in the breathtaking, enigmatic Dame à la Licorne tapestries at the Cluny museum in Paris--performing a rite she had embraced as her duty. Even when she was thrown from the arms of one pair of men, left for a nanosecond to float unsupported in space, then caught by a second pair, she maintained an unperturbed arabesque.

She was equally amazing in the Choleric section of The Four Temperaments, a fiery figure who looked dangerous to touch but one that kept the world steady on its axis. Even a small mishap revealed her phenomenal equanimity. In the introduction to the second pas de trois of Agon, she balanced on pointe on one foot, looking directly out at the audience--and somehow failed to connect with her supporting partners' hands. Slowly and serenely, she tilted sideways, like Pisa's tower, without a tremor, until she was rescued. A few minutes later she was performing the intricately timed solo to castanets as of she'd never been anything but safe.

Reichlen has so perfected the qualities that constitute her profile, it might be time for City Ballet to try casting her against type--say, in roles that require warmth and voluptuousness. There may be more to her than meets the eye.

Sara Mearns has been whipping through the City Ballet's repertory at a pace her admirers can barely keep up with. I'd never imagined the company would think of her for Concerto Barocco, but there she was, lending her luscious fluency to just the right degree as a foil for Maria Kowroski, the queen of adagio dancing, who naturally got to do the central duet with the sole man in the ballet.

Mearns's role in the final section of Episodes was a triumph. After all the ingenious, unsettling dislocations Balanchine created to the stark atonal Webern music used for the bulk of the ballet, here he matched the composer's tribute to Bach--an arrangement of the Ricercata in Six Voices from A Musical Offering--with choreography that, still spare, restores the idea of harmony. Mearns was a natural for the part.

Two other key women on the roster, Maria Kowroski and Wendy Whelan, were to be praised more for the intelligence with which they conceived their roles than for sheer theatrical impact. Kowroski, luminous early in her career, now fails to engage fully with what she's doing; many of her effects are beautiful--in Monumentum she was crystal clear and at the same time tender as a rose petal--but still remote. Her performance in Stravinsky Violin Concerto, partnered by Amar Ramasar, earned a second curtain call, I felt, because she had understood the nature of the choreography and how she could dance it most effectively, not because she appeared to be experiencing the moods and events it implied.

Though Whelan still looks as if she's made of spun steel, her technique has, unavoidably, been ebbing in recent years; her projection of acute sensitivity, increasing. While she's been unequalled among her peers for her interpretation of roles conceived in the land of regret and pain, her natural range has always been limited. She has worked admirably to extend it, and frequently succeeded to a point, but she still lacks the confident joy and the claim to conventional beauty that are hallmarks of the traditional classical ballerina. But then the New York City Ballet is hardly a traditional classical ballet company.

Thanks to George Balanchine, the company is the chief custodian of a huge percentage of the most remarkable ballets created in the 20th century. As the "Black & White" festival proved by giving such pure and energized productions of the abstract works, Balanchine's ballets cannot be condescendingly dismissed as monuments of the past, relegated to the history books, thought of as relics for a museum. They remain signposts pointing to the future of the art.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

New York City Ballet: The Seven Deadly Sins / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / March 11, 12, 13 14, & 15, 2011

Working Girls: Patty LuPone, Wendy Whelan, and company men in Lynne Taylor-Corbett's The Seven Deadly Sins

Photo: Paul Kolnik

New York City Ballet's spring season gala on May 11 focused on the company's new production, The Seven Deadly Sins, choreographed by Lynne Taylor-Corbett, credit-wise a practiced hand at dance-theater. It looks pretty much born yesterday, but the Kurt Weill - Bertolt Brecht cabaret-style melding of music, dance, and spectacle has a history both with George Balanchine and the company.

Balanchine produced his first version of the piece in Paris for Les Ballets 1933 in that year. It was far from universally acclaimed, but the choreographer never forgot it. In 1958 he made a revised version for the 21-year-old Allegra Kent, a flexible creature of fantasy who had captured his imagination. Kent danced the lithe Anna 2, a naive idealist. Lotte Lenya, Weill's wife, famous for a rough-edged voice that resonated tough experience, sang Anna 1, the cynical tyrant. Plot-wise, the two are treated as sisters, but are designed to represent the morally conflicting halves of a single person.

Back home in Louisiana, their righteous, poverty-stricken family--mom, pop, and two brothers, all sung by men--send the young women across America, the land of opportunity, with the mission of earning enough money to buy them a proper house to replace their poor people's shack on the banks of the Mississippi.

Sweet Love Remembered: Whelan and Craig Hall

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The project takes a Biblical seven years and visits to seven metropolises, during which the white-souled Anna repeatedly fails as a dancer (indeed, an artist of any kind) and is forced to eke out the required funds as a prostitute. Miraculously, she retains her guilelessness, though the degradation finally kills her.

I saw the 1958 production while I was still at school. I remember Kent and Lenya distinctly, no doubt because each was unforgettable in her own way. I don't recall many specifics about the production, but I can still feel--or is it taste?--its atmosphere: decadent, sordid, sinister, yet unable to penetrate Anna 2's natural purity.

Taylor-Corbett's take on the material is a strangely tame revue. It has no atmosphere and no affecting drama. Even the melodrama falls flat. Dire and ironic situations are acted out--say, Anna 2's submitting to sex with a rich john, while the true love she's found waits for her in the bed of a look-alike hotel room next door--yet nothing ever really seems to happen to anyone. This is not sound theatrical policy and certainly not good for a production that requires a heavy sardonic tone.

Sisters Under the Skin: LuPone and Whelan

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Patti LuPone, a Broadway-type singer with a dynamo voice, and Wendy Whelan, City Ballet's senior ballerina, carried out their assignments well, Whelan working in her airy lyrical mode to reflect her character's unimpeachable innocence. However, neither was magical. Nothing they did was likely to arouse the audience's empathy. Similarly Beowulf Boritt's sets and Judanna Lynn's costumes, attractive on their own terms, failed to evoke the sleazy and mordant tone of the culture they needed to describe.

I could register other complaints, such as the distracting fact that it's often hard to connect the sin named in the program with the representation it's given on stage and that Anna 2's physical modesty is overdone to the point of monotony. Still, none of this would matter if the show had only taken fire instead of remaining dutifully workmanlike. Instead it's like a coloring book in which the crayon has been forbidden to venture outside the lines.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Paris Opera Ballet School / Palais Garnier, Paris / April 7, 9, 11, & 12, 2011

The spectacularly ornate Palais Garnier opera house, home to the Paris Opera Ballet, can be daunting to a visitor, given its grand staircase, paired pillars of marble in exotic colors, elaborate gilded carvings, and profusion of crystal chandeliers. Nevertheless it's a perfectly suitable showcase for the children, adolescents, and very young adults being trained in the company's celebrated academy. Their accomplishment is equal to the effusively regal setting while their unaffected manner is an antidote to it.

Linked: Students of the Paris Opera Ballet School in John Taras's Designs for Six

Photo: David Elofer

While I was spending part of April in Paris, I saw two performances that the students gave at the Opéra, as its called: two different casts in Pierre Lacotte's back-to-the-original version of Coppélia, prefaced by John Taras's Designs for Six.

Taras, who died in April of 2004, some two weeks short of his 85th birthday, made a substantial contribution to the classical dance world, as dancer, choreographer, and ballet master for key companies on both sides of the Atlantic. As I recall him, from a slight acquaintance during his many years with the New York City Ballet, Taras was a very nice man, a gentleman and--more telling--a gentle man, modest and soft-spoken. That personal quality infuses the ballet for which he's best known, Designs for Six, the Paris Opera Ballet's title for the work he created in 1948 for the Metropolitan Ballet as Designs With Strings, and subsequently called Design for Strings. The music, accessible and agreeable, is the second movement of Tchaikovsky's Trio for piano, violin, and cello in A minor.

It's a simple, well-made ballet, which takes its inspiration from Balanchine. It lacks the rigor and invention of the master, to be sure; still it is lovely to look at, intelligent, and exquisitely understated. What's more, it makes a fine vehicle for young dancers on the threshold of their professional careers because it benefits from the fresh, innocent quality of their youth while displaying the technical accomplishment to which they've devoted the better part of their childhood and early adolescence.

I had seen the ballet several times over the years in several different places--where and when I can't recall--but never until I saw it performed by the advanced students of the Paris Opera Ballet School this spring, did I understand what force it could gain from a young crew of talented, impeccably trained dancers. This was immediately apparent from the striking illustration of classical placement in the opening tableau--a statement about exactitude tempered by grace.

That first image has the sextet--four women and two men--posed together in silhouette against a blue-sky cyclorama. Very slowly, as if at the pace of a sunrise, the light increases to illuminate the flesh tones of the dancers' skin against the jet black of their simple costumes and to filter through the net of the women's short tutus.

Variations on a Theme: Students of the Paris Opera Ballet School in Designs for Six

Photo: David Elofer

Once the figures begin to dance, they give the overall impression of spooling out an uninterrupted chain of pure beauty. At the same time it's clear that Taras intends to demonstrate the myriad ways in which six bodies can be deployed. In keeping with his temperament, he's content to do this unobtrusively, and so avoids the self-congratulation that Jerome Robbins, who excelled at cleverness, put into such a task.

Memorable among the inventive small segments is a women's duet performed now with crossed arms and linked hands, now with unison dancing alternating with mirror-image movement. There's also a zippy trio for women, complemented by another pas de trois for the fourth woman and the two men. One passage includes lots of daisy-chaining, though the tactic is admittedly somewhat stymied because it can't travel much with so few participants. (This is probably the only awkward passage in the piece.) Towards the end of the ballet, the full cast revels in some Spanish-dance flourishes with good humored panache.

The centerpiece of the ballet is a pas de deux of grave beauty that makes its young man and woman look like an emblem of commitment. It's a subtle reminder that teen-age passions can run very deep and thus deserve to be taken seriously--indeed, honored.

Introduced with this duet is a delicately proposed subtext that gives the ballet its particular charm and its ability to move the audience. The six figures, it suggests, constitute a group of friends firmly bonded by their dedication to an all-consuming enterprise--let's call it training for the classical ballet stage--that isolates them from the ordinary world. Their entire universe, apart from mastering their art, consists of each other. Then love intrudes and, as it so often does, catastrophically threatens friendship. Once it's introduced with the pas de deux, this idea tinges the rest of the ballet.

The "veil" is so sheer, however, as to be invisible to some viewers, who see Designs for Six simply as a graceful piece without a theatrical bone in its body. In truth, its good manners so consistently govern the show that when, at the end, the dancers return to the silhouetted tableau in which we first met them, they might be assumed to have had no transformative experience at all. They can be read simply as the willing prisoners of beauty.

Throughout the performances I saw, all the young dancers had an air of striving for something beyond what they had already mastered.

When you watch a bevy of good dancers you're unfamiliar with, though, there's almost always one that seizes your eyes, and often your heart as well. For me on this occasion it was a young man named Mathieu Contat, dancing the main duet in one of the performances I saw of Designs for Six and, on my second viewing of the student program, playing Franz in Coppélia. He's a youth with a body admirably proportioned for eventual danseur noble roles, excellent technique that is still in the process of gaining an adult strength and force, and an irresistible boyish charisma.

In the intermission, a woman of a certain age who exuded Parisian chic, whom I'd asked if she knew the young man's name, introduced me to Contat, who had appeared in the front of the house in ordinary youth garb (jeans, etc.), exuding an offstage version of his onstage charm (self-confident yet respectful of his audience, happy in being where he is and doing what he does). After we chatted briefly, I asked if I could know how old he was. "Seventeen," he admitted, with some apparent doubt as to whether that was too old or not old enough.

The more ambitious item on the program--in sheer number of dancers and variety of dancing styles--was a looking-backward version of Arthur Saint-Léon's 1870 Coppélia. At its heart lies its Delibes score, which seems to dictate dancing as it swings from effervescence to romantic sweetness, folk dance, and the practical--sometimes nearly farcical--dramatic needs of the moment. It nearly choreographs itself. Invariably, it inserts itself into the listener's head and--for good or ill--remains there for days.

Pierre Lacotte, who has made a specialty of reviving 19th-century ballets by going back to the originals as far as is practicable, set his new-old version of the ballet on POB's students a decade ago and it has usefully remained in the school's repertory, allowing children and tweens to mingle with the young adults playing the principal roles. It certainly has its delights, despite its occasional unevenness of tone and its failure to hold a candle to the Russo-American Danilova-Balanchine version of 1974, which knows just when (in the third act) to abandon history for the confident originality of genius.

Les Petits Rats: Young students of the Paris Opera Ballet School in Pierre Lacotte's version of Coppélia

Photo: David Elofer

Lacotte's production remains unquestionably good for the school, and not merely because it offers an alternative to the parent company's most recent version of Coppélia--a reportedly hapless and gruesome take on the ballet by Patrice Bart. (Bart's excuse was making the ballet more like E.T.A. Hoffmann's The Sandman, a dark-magic tale on which Saint-Léon's Coppélia was loosely based.)

Lacotte's Coppélia shows the students the point of significant aspects of their training. Throughout their years of meticulous classical dance instruction, they are also taught acting, mime, and folk dancing--to encourage their imagination and enable them able to give creditable performances in these genres onstage. This history-driven Coppélia also helps the developing dancers realize that the parent company honors its backstory, that the repertory of the past is linked to today's innovations, and that the dancers of today and tomorrow have an authentic connection to their predecessors.

As a result, when a bevy of dancers surges over the stage in red boots and thick-heeled character shoes, you feel the weight with which the feet strike the floor, the powerful spring in the knees, the feisty carriage of the upper body, and the animal exuberance of bodies responding to lusty rhythms. What you don't see, mercifully, is ballet dancers so bored by playing a corps of peasants that they do so half-heartedly, without zest or conviction.

The acting and the mime taught in the school results in the creation of distinct, believable personalities onstage. From the moment we first see her, the ballet's heroine, Swanilda, displays her spirited temperament. In a vivacious mime monologue she has us understand that while she's truly in love with her boyfriend, Franz, she can't understand--and doesn't intend to put up with--the young fellow's attraction to that pretty girl sitting so placidly in her strange neighbor's window.

Put to the Test: Paris Opera Ballet students Marie Varlet and Germain Louvet as Swanilda and Franz in Coppélia

Photo: David Elofer

Swanilda's straying beau is something of a dolt, though one with considerable appeal if very few brains. During the stalk of wheat test--if you can hear the seeds rustle, your lover is true--with their whole rural community watching, he hasn't the sense even to pretend he hears the happy message.

No matter, Swanilda is clever enough for both of them and feisty enough to let nothing stand in the way of her getting what she wants. She may be a girl who's reduced to tears by her sweetheart's skewering, then trampling on the butterfly she was blithely chasing, but she's willing to trick him when his foolish heart strays to the dolly in the window. What's more--much more--she's ruthlessly cruel to the doll's creator, Dr. Coppélius, pretending she is his cherished automaton come to life and then disabusing him of his dream.

I saw Marie Varlet and Alizée Sicre as Swanilda; the latter is the more febrile and ambitious, perhaps for stardom. Both Germain Louvet and Mathieu Contat played Franz, combining an appropriately youthful lack of sophistication with technical élan.

Idée Fixe: Paris Opera Ballet student Natan Bouzy as Dr. Coppélius in Coppélia

Photo: David Elofer

Most notable of all is the student rendering of Dr. Coppélius, because those trusted with the role are evidently allowed considerable leeway in honing their own interpretations. Natan Bouzy gave the role a sound traditional interpretation, playing Coppélius as a gimpy old man obsessed by an idea any normal villager--and indeed anyone in the audience--would dismiss as nutty. His signature image is the greedy hands with which he tries to seize Franz's life spirit to implant it in Coppélia.

Julien Guillemard offered an unusually creative interpretation. His Coppélius was not even old, but simply an outsider intent upon his improbable vision. Despite the community's scorning him as a reclusive, half mad fellow, he seemed truly to believe that, through the arcane instructions in his gigantic book of spells, he could bring his beautiful automaton to life, give her not merely the human breath that would transform her motion from staccato to lyric but also a heart that could awaken to love.

Guillemard's portrayal has not yet accumulated the fascinating detail that distinguished the two most original and effective men I've seen in the role--Niels Bjørn Larsen of the Royal Danish Ballet and Shaun O'Brien of the New York City Ballet. But they had been evolving their characterizations for decades--to the point of being able to improvise on any part of them in performance. Meanwhile Guillemard was utterly convinced of, and convincing in, the persona he has worked out so far.

All's Well That Ends Well: Swanilda (Marie Varlet) and Franz (Germain Louvet) get married

Photo: David Elofer

There was so much to like in this program and it made such an optimistic prediction for the future that, after seeing it, the only thing I wanted was to see it again. And I did.

POSTSCRIPT:

People agreeing with the conventional assessment of the relative value of pictures and words may want to watch a six-minute excerpt on YouTube from the current three-act production of Coppélia that is pretty much what I saw, except for the mature Lacotte's appropriating the role of Dr. Coppélius for himself. The Swanilda is Charline Giezeendanner; Franz is Mathieu Ganio. To view it, click here.

YouTube also harbors a two-act version of Coppélia performed by the POB students in 2001 and credited to Claude Bessy, then the director of the school, and Pierre Lacotte, after the version of Albert Aveline. A shade over one hour long, it shows a bit of the Palais Garnier, outside and in, some sweet backstage footage, and the full performance. To see it, click here.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary