Seeing Things: January 2011 Archives

New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 22, 2011

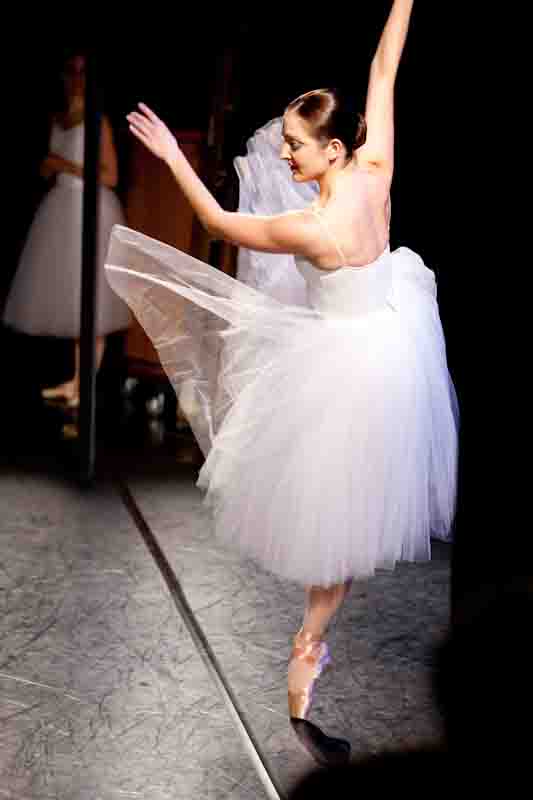

Prayer: New York City Ballet principal dancer Wendy Whelan with SAB students in George Balanchine's Mozartiana

Photo: Paul Kolnik

On January 22, the 107th anniversary of George Balanchine's birth, the New York City Ballet marked the occasion with two programs, matinee and evening, composed entirely of the master's work, along with supplementary activities that made the day a marathon of celebration. The doings were belatedly given the odious (and impertinent) title "Saturday at the Ballet with George"; I sense the work of the Marketing department here, but let that pass.

The works performed were: Walpurgisnacht Ballet, Duo Concertant, The Four Temperaments, Cortège Hongrois, Mozartiana, Prodigal Son, and Stars and Stripes. As anyone who follows the City Ballet's seasons can tell you, these pieces were hardly chosen from a list of Balanchine's greatest works ever, not even from Balanchine works recently in the company's repertory, but--for practical reasons, I assume--from the pieces rehearsed for performance in the period immediately surrounding this ostensibly special event.

Prodigal Son (1929), The Four Temperaments (1946), and Mozartiana (1981; Balanchine's last major ballet) are unassailable choices. Any one of them, standing alone, proves the maker's genius. But a dozen others, at the very least, equal those achievements. Think Apollo (complete with the birth scene; 1928); Serenade (1935; Balanchine's first ballet for American dancers); Concerto Barocco (1941); Symphony in C (1947); Divertimento No. 15 (1956); Agon (1957); Symphony in Three Movements (1972). And then there's the 1960 Liebesleider Walzer. Admittedly it's too long if you need to put at least three works on a program--unless you make one of the other pieces on the bill the eight-minute Monumentum pro Gesualdo (1960). Subtle and luminous, this brief ballet is one of my personal favorites. Every devoted Balanchine watcher will have his or her own.

Wrath: Teresa Reichlen, partnered by Jared Angle, in Balanchine's The Four Temperaments

Photo: Paul Kolnik

A persistent problem at City Ballet--and one that could be corrected--remained in evidence: casting against type. Take 4Ts again. Of the leaders of the main segments, only one was just right: Teresa Reichlen in "Choleric," a long-limbed giantess whose fierce legs can set the stage on fire, while her tiny head remains poised, ever-alert. Sébastien Marcovici, a seasoned, bulky-figured dancer with dramatic resonance in "real man" roles, was hardly the ideal choice for "Melancholic." That section is usually awarded, rightly, to a lithe, vulnerable-looking fellow who's immediately convincing--and appealing--as a weak-willed poetic type given to self-pity.

Jenny Somogyi and Jared Angle, as the "Sanguinic" pair that should anchor the ballet with serene classicism and confident optimism, were stolid in their exactitude. A video of their performance might well be a godsend to a person staging the ballet on a new cast, but the pair offered its immediate audience nothing beyond steps immaculately rendered. Amar Ramasar, at the peak of his power and absolutely glowing, is simply the antithesis of the "Phlegmatic" mood; he's all grace and exultant joy, when he should be tying himself into knots.

On the whole the dancers of City Ballet, over 90 strong, provide endless fascination for witnesses to the trajectory of their careers. At every level of experience and ability, there is something going on. Take the following three, all easy to notice in the seven ballets danced on the 22nd.

America the Beautiful: Erica Pereira in Balanchine's Stars and Stripes

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Erica Pereira, a soloist who unvaryingly shows enormous promise in the many challenging roles she's assigned, is coming along well. Her purity of technique is amazing, yet there's nothing mechanical about it. While she aces every single step with uncanny precision, she still makes each one look soft, even downy. There's a calm about her, too, that contributes to her air of effortlessness.

Despite her gifts, Pereira still hasn't come fully into her own. With her small, slender figure and sweet face, she looks like a child, and perhaps there's something of an obedient and much-loved child in her dancing. She doesn't yet dare to "own" the stage, to project out into the wider world from the spot assigned to her. She makes me think of a exquisite miniature displayed (and imprisoned) in a glass capsule.

I have great hopes for Pereira. I remember first seeing her, toward the end of her student days, rehearsing for SAB Workshop. She was to dance the female lead in Balanchine's Square Dance. She finished a solo and waited for the ballet mistress's corrections. There was nothing to correct except the dutiful look--stern and a little gloomy--that her face took on when she danced. "How about the smile?" teased the ballet mistress. Pereira smiled. It was like seeing Garbo laugh.

Georgina Pazcoguin has been noticeable in the company for some time, essentially as the latter-day equivalent of a character dancer. She's been in her element, for instance, in Jerome Robbins's Fancy Free, as the girl with the red shoulder bag--a foil for her lyrical chum who gets to do the romantic pas de deux. Radiating a personality that doesn't take any nonsense, she carved out an identity as a feisty dancer, all vitality and edge. Lately, though, she's being seen differently, "rediscovered," as it were, as a classical dancer. On the 22nd she had demi-soloist roles in both Walpurgisnacht and 4Ts and acquitted herself beautifully, as if she'd temporarily blotted from her memory the dynamo she was as Anita, lashing the air with her red skirt in Robbins's West Side Story Suite.

And then there's Sara Mearns, a principal dancer who has acquired a huge following in the City Ballet audience. I think the public enjoys seeing an artist who dares to break the house rules of her profession or at least bend them to work with her unique gifts. Mearns's plasticity, her abandon, and her ferocious power make me think of legendary stage presences like Isadora Duncan and yesteryear's opera divas. It goes without saying that she shares their instinct for drama.

My Space: Sara Mearns in Balanchine's Cortège Hongrois

Photo: Paul Kolnik

In Cortège Hongrois--one of Balanchine's several spinoff's from Petipa's Raymonda--Mearns's evocation of a generic princess suggests that the young woman in tutu and tiara encases a vulnerable heart in imperious postures and sculptural poses suggesting great metaphorical weight. Her big solo begins and ends with the same two moves--a firm clap of her hands followed on the next beat by one hand's reaching behind her head, her elbow winged out, as her upper body arches proudly.

In between this phrase and its repetition, she seems to go through a troubled rumination on her duty as the ruler of her country, which is fatally incompatible with what she owes to her own pleasure in love. (Petipa had a narrative to help him; Balanchine had nothing but steps to music.) She appears to decide, courageously and firmly, in favor of the nation, but it's not her choice that's important. Rather, it's the process of expressing thought and feeling through essentially abstract dancing that's so thrilling. This is a Mearns specialty, and it's one of the things that makes for the fans' adulation. And mine.

"But first a school": Peter Martins instructing students of the School of American Ballet

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The richest of the day's supplementary events was the 50-minute condensed class Peter Martins gave onstage to a group of School of American Ballet pre-professionals. Ballet Master in Chief of City Ballet, Martins is also Artistic Director and Chairman of Faculty of SAB, the company's feeder academy. The main thrust of the session was to reveal to the audience how and why City Ballet's style, built on Balanchine's precepts, is distinctive--as sharp and precise as a surgeon's scalpel, charged with energy, and musically acute. Martins's teaching manner, a suave mix of authority and humor, is clearly effective. I thought I already knew a lot about the subject, but I also learned a lot.

Dance followers had been asking one another right up until the day-long program began, if what we saw in the course of it would yield a true reading of the Balanchine repertory's present condition at City Ballet. And what would that reading be? I thought of these questions again as I and my valiant companion for the day staggered in the bitter cold, eyes and minds flagging, to the Columbus Circle subway station. I didn't ask them aloud because, as I realized, I haven't yet come to terms with the fact that, with the choreographer gone, nothing is likely to compare with the performances I witnessed during his lifetime. This is not a complaint; this is simply a fact.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Works & Process: Pacific Northwest Ballet: Giselle Revisited / Guggenheim Museum, NYC / January 9 (2 performances) & January 10, 2011

Works & Process, holding forth since 1974 at the Guggenheim Museum on New York's Upper East Side, has been, at heart, a lecture-demonstration series--Show & Tell for adults attracted by the arts. The programs devoted to dance have traditionally hewed to the simple, sensible pattern of alternating The Talk and The Walk. Spoken explication and anecdote (everybody loves to hear the backstage stuff) about a particular production or person "in the news"--most often, about to be seen in New York--took their turn with members of the company involved dancing excerpts from the coming show on the museum's bath sheet-sized stage. (The spatial restriction in height as well as width long ago became part of the evenings' charm.)

Body Language: Carla Körbes and Seth Orza in rehearsal for Pacific Northwest Ballet's new, scholarship-driven Giselle. Excerpts from the production, along with a detailed discussion of the approach, were featured recently in the Works & Process series at the Guggenheim Museum.

Photo: Jesson Mata

The most recent W&P presentation--"Pacific Northwest Ballet: Giselle Revisited"--concerned itself with the highly respected Seattle company's new production of the 1841 Romantic classic, which has been based on the investigations of a pair of dance scholars. The far more usual method of mounting a new setting of a nineteenth-century ballet is to have dancers and stagers hand down the traditional choreography as they recall it, consciously or unconsciously emending it, with, on occasion, more radical alterations coming from a choreographer given to new concepts.

In this case the primary work was done in libraries, with the scholars going back to the earliest dance notation scores available and other evidence-on-paper, as I'd call it. Doug Fullington, who had already done some of this back-in-the-day kind of work with PNB, reconstructed the Giselle choreography from documents in the Harvard Theatre Collection that had been notated using a method developed in Russia in the 1890s by Vladimir Stepanov. Although Giselle was created in France, with choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot, the Giselle we know best today derives from a revision mounted for St. Petersburg's Mariinsky (aka Kirov) Ballet by the celebrated choreographer and ballet master Marius Petipa. The nineteenth-century Russian classics so revered today were transmitted to the West via Stepanov scores, such as the one for Petipa's Sleeping Beauty, which Nicholas Sergeyev used to mount the ballet on England's Vic-Wells (now the Royal) Ballet. "He arrived," Ninette de Valois, founder of the British company, wrote, "with his tin trunks full of his notation-books . . . which [he] managed to bring out of Russia with him."

Marian Smith, billed as the Historical Adviser to the production, abetted Fullington's work by consulting French records from the period of the ballet's creation and drawing evidence from sources such as Cyril Beaumont's 1944 in-depth study, The Ballet Called Giselle.

PNB's Artistic Director, Peter Boal, is credited with the staging of the new production. I assume this means making the intellectual knowledge recently gleaned about Giselle cohere into a theatrically convincing work for a stage on which no words exist.

Near-Death Experience (in rehearsal): Körbes's Giselle, emerged from the grave, attempts to rescue Orza's Albrecht, condemned by the Queen of the Wilis

Photo: Jesson Mata

Fullington explained some of the general differences he found between the nineteenth-century Giselle revealed by the written records and the prevailing style in which the ballet is danced today. Virtuosity, he pointed out, means different things in different periods. Nineteenth-century Romantic choreography emphasized swift, light steps (call it fleetness). Today, however, the emphasis is on elevation (the dancer's ability to surge powerfully through the air at astonishing heights). And then mime, so disrespected nowadays, was formerly cultivated as an indispensable part of dance expression. Gesture was never empty or mechanical; it had to be rendered with thought and heart, so as to express a specific meaning.

Few people can read dance notation of any kind and dance professionals themselves are instinctively wary of it, since their art is deeply visceral and, unlike music, difficult to understand as a set of symbols. However Fullington was almost dangerously persuasive as he described his work--simply because of his contagious enthusiasm for his discoveries, and then for an easygoing charm that avoids any hint of schoolmasterish dryness or patronizing. The final test of his method will come with the public's response to the finished production. The new-old Giselle will be shown first in Seattle, June 3-12; our appetites having been whetted, it's a pity we're not seeing it in New York.

The four dancers present to make the scholars' theories come alive were quite wonderful in the excerpts of Giselle performed according to the tradition that has evolved until now, and then as it has been affected by the newly implemented evidence of words and signs--with Fullington and Smith gracefully explaining the differences along the way.

Carla Körbes's dancing (as Giselle) reminded me that the term ballerina is much misunderstood. Too often, among English speakers, it's taken to mean simply dancer (gender: female). Yes, that's what it means in Spain, but when you hear it in, say, the intermission buzz at Lincoln Center, it has a far more specific and intense connotation. It designates a female classical dancer who has extraordinary gifts of technique, style, musicality, drama--and compelling (if often subtle) charisma. A ballerina illuminates the entire stage on which she performs.

I always thought Carla Körbes might become a member of that rare breed, from her years with the New York City Ballet--futile in terms of her advancement, though she was a perennial stand-out in the corps and small roles--through Boal's co-opting her for PNB. This hasn't happened yet. So many things besides talent combine to shape a dancer's career: desire, determination, luck, fate. Nevertheless Körbes's performance at the W&P event made life seem suddenly larger than you'd imagined, more charged with meaning.

The Girl Who Can Do Everything: Carrie Imler, who danced Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis; Berthe, Giselle's mother; and the Peasant pas de deux in the Works & Process program about Pacific Northwest Ballet's new Giselle

Photo: Jesson Mata

In the course of the presentation, both Boal and Fullington referred to Carrie Imler as "the girl who can do everything." They needn't have bothered; just 60 seconds of her dancing makes that clear. This type of performer--the current prototype is New York City Ballet's Tyler Peck--is a technical whiz with an outgoing personality, often the backbone of a company. (A lyrical ballerina--think Allegra Kent--is in charge of its soul.) Not haunted by second thoughts, Imler's type raises the viewers' spirits and secures their confidence in the show. She was vivid on this occasion in excerpts from three roles that couldn't be more different: Myrtha, Queen of the Wilis; Berthe, Giselle's mother; and the Peasant pas de deux.

As Imler's partner in the pas de deux, James Moore was memorable. He has the comparatively short, robust body of a character dancer but is entirely a danseur-noble type in his dancing, with the purity of execution you'd expect from an artist who had Boal as model and mentor. Moore must have a dramatic imagination too; he made a Hilarion for whom you felt sympathy, despite his rough-hewn aspect and the nasty deeds that come from desperation. His Hilarion loves Giselle with utter sincerity, which, of course, is more than one can say of Albrecht.

Seth Orza, who plays Albrecht, certainly has the anatomy of a prince (albeit in disguise) but something stymies his performance, making him a little stiff, even a little awkward, slightly under-equipped when it comes to energy and personality. But who knows--another occasion might find him all fired up.

Allan Dameron, PNB's acting music director and conductor, accompanied the dancing with the panache of an extroverted pianist giving a solo concert at Carnegie Hall. His contribution was certainly the opposite of the typical guy--you've seen him in the old movies--who played for dance classes in the studios of yesteryear. Undernourished, shabbily dressed, sketchily shaved if at all, with an unfiltered cigarette perennially between his lips, that poor fellow played indifferently on the decrepit piano allotted to him and never looked at the dancers once. Perhaps it's best that some performances remain modernized.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Trisha Brown Dance Company: Works by Brown from the early 1970s, presented in conjunction with the exhibition On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century / Museum of Modern Art, NYC / January 12, 15, & 16 (2 performances), 2011

Trisha Brown has been choreographing for half a century; from today's vantage point her development can safely be termed evolutionary. Examining the path of her career, it's easy to trace the innate logic that led her from simple (nevertheless ingenious) pedestrian ideas, actions, and gear to complex creations, rich in theatrical artifice, that somehow remained pure. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this journey is the interest aficionados of the arts still take in Brown's works of long ago.

As part of its On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century exhibition, the Museum of Modern Art scheduled performances on January 12th, 15th, and 16th (at 2:00 and 5:00 each day) of Brown's Sticks (1973), Locus Solo (1975), Scallops (1973), and Roof Piece Re-Layed (a version of the 1971 Roof Piece).

Brown's works of the early Seventies--the period in which it became clear that she was a leading figure in what would be called postmodern choreography--were as fresh as lemonade made from scratch, as I remember it from my first visit to Paris. When you ordered un citron pressé in a modest to downright humble café, you were brought a pitcher of cool water, an empty glass tumbler, a lemon, a small serrated knife, and a downsized reamer (used in old-fashion kitchens to squeeze the juice out of citrus fruits). As I recall, there was a basin of sugar already on the table; ice was unheard of. The lemonade you produced with this simple equipment was the very essence of the drink--just as Brown's early pieces offered the salutary shock of dancing that's been reduced to its essentials. Today, four decades after Brown created them, those dances still look new.

The choreography is divinely matter-of-fact. Though most of the action requires extraordinary skill, the tone with which it's executed is unemphatic--gentle and calm, full of reticent grace. Should anyone ask you what's going on in these dances, you might even say that each performer simply executes the task she/he has been given.

Simply executing the tasks one has been given. Isn't that a possible prescription for a satisfying life? Those who think not must rest content with the dancers' echoes of the incomparable fluidity Brown displayed in her performing days and the constant evidence in her choreography of a singular intelligence and a wit expressed in swift, tiny flashes, like the lights of fireflies in a darkening sky.

The MoMA program took place in the museum's Atrium, from which you could gaze down on the expansive street-level lobby and up to look-out points on four floors of gallery space. The venue itself is alive with architectural possibility. The audience, standing or sitting on the Atrium floor, bordered a huge square marked off for performance, the onlookers becoming a living frame for the dancing.

Balance Beams: Members of the Trisha Brown Dance Company in Brown's Sticks at MoMA

Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The program opened with the 1973 Sticks in which four dancers in snug long-sleeved white jerseys and loose white pants partnered with wooden beams maybe two inches square and ten feet tall. Working in unison, the performers seemed to be the puppeteers and the sticks their puppets, as they executed extraordinary feats of balance so that the sticks could lean at precarious angles or meld, ends touching, into a single line that floated, wavering just a little, a couple of feet above the ground.

Room of One's Own: Diane Madden in Brown's Locus Solo

Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Locus Solo (from 1975) was performed by Diane Madden, who has worked--and bonded--with Brown for some three decades. Today, she's the company's rehearsal director. A small, strikingly lithe woman with a blond ponytail and a visible delight in dancing, she took possession of a small square marked off dead center in the larger space. Her movements, themselves straight-edged and scrupulously within the indicated boundaries, looked as if she were exploring the parameters of her domain--and its possibilities, rather than its restrictions. After a time, the addition of some leaning, almost falling moves to the strictly vertical ones allowed Madden to suggest a lyrical vein in her activity, though she took scrupulous care not to overemphasize it. Finally Brown's and Madden's combined alchemy revealed that the small dancing ground was larger than we'd first imagined. It had a third dimension--height; it was really a cube. What more could anyone want?

The program's most complex piece was Roof Piece Re-Layed, an ingenious adaptation of the 1971 Roof Piece that must have had pavement-bound spectators tilting their heads backward to ogle the tops of buildings stretching downtown and then westward from a starting point in SoHo. The original piece--which I'm sorry to say I know only by hearsay--had 15 dancers, clad in red for visibility, positioned at least a block apart on the route's rooftops, transmitting a string of gestures down the line to one another as they stood in the sky. None of the dancers could see more than a few of the others. The starter, Brown herself, improvised the initial material. Once the wordless semaphored "message" reached the end of the line, it traveled back again to the beginning, modified as is a verbal message in the children's game of Telephone. Among the participants were Liz Thompson, Valda Setterfield, David Gordon, Douglas Dunn, and Sara Rudner.

Do You Read Me? Brown's Roof Piece Re-Layed at MoMA

Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

In the re-imagined (as they say these days) version for MoMA, the dancers--eight of them this time--were again in red. Six appeared at various levels of the Atrium's walls behind rectangular glass panes of different sizes. Two were unshielded; you could have reached out and touched them, if you dared. One of these, a man, was down in the lobby that the Atrium overhangs. Standing on a low block near the Sculpture Garden, he looked like another statue that had simply added motion to its traits. Madden stood out on the Atrium floor looking like--well, Madden, who, once seen, can't be forgotten.

As in the original version of the piece, any one dancer could see only a few of the others. It seemed impossible to decipher which of them was the "starter." To me the material for all eight rooted-in-place bodies looked memorized, not improvised, because it seemed to be accurately copied as it traveled. I could have asked about this afterward but I didn't. I didn't really want to know. In an era like ours, which has made privacy extinct, art at least should be allowed to keep some of the mysteries that are part of its (al)lure.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

American Ballet Theatre: The Nutcracker / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / December 22, 2010 - January 2, 2011

A tree grows in Brooklyn--with a vengeance. At BAM's Howard Gilman Opera House, American Ballet Theatre's brand-new Nutcracker, by Alexei Ratmansky, followed on the heels of the Mark Morris Dance Group in The Hard Nut. Same evolution-of-the-girlchild theme (more or less), same glorious Tchaikovsky score. Musically, you can't fault the nation-wide and ever-expanding Nuts endeavor. Choreographically and theatrically, it's another story. (Despite the popularity of his own version, and with due respect to Balanchine, Morris claims that Walt Disney did the best job--in the evergreen movie Fantasia.)

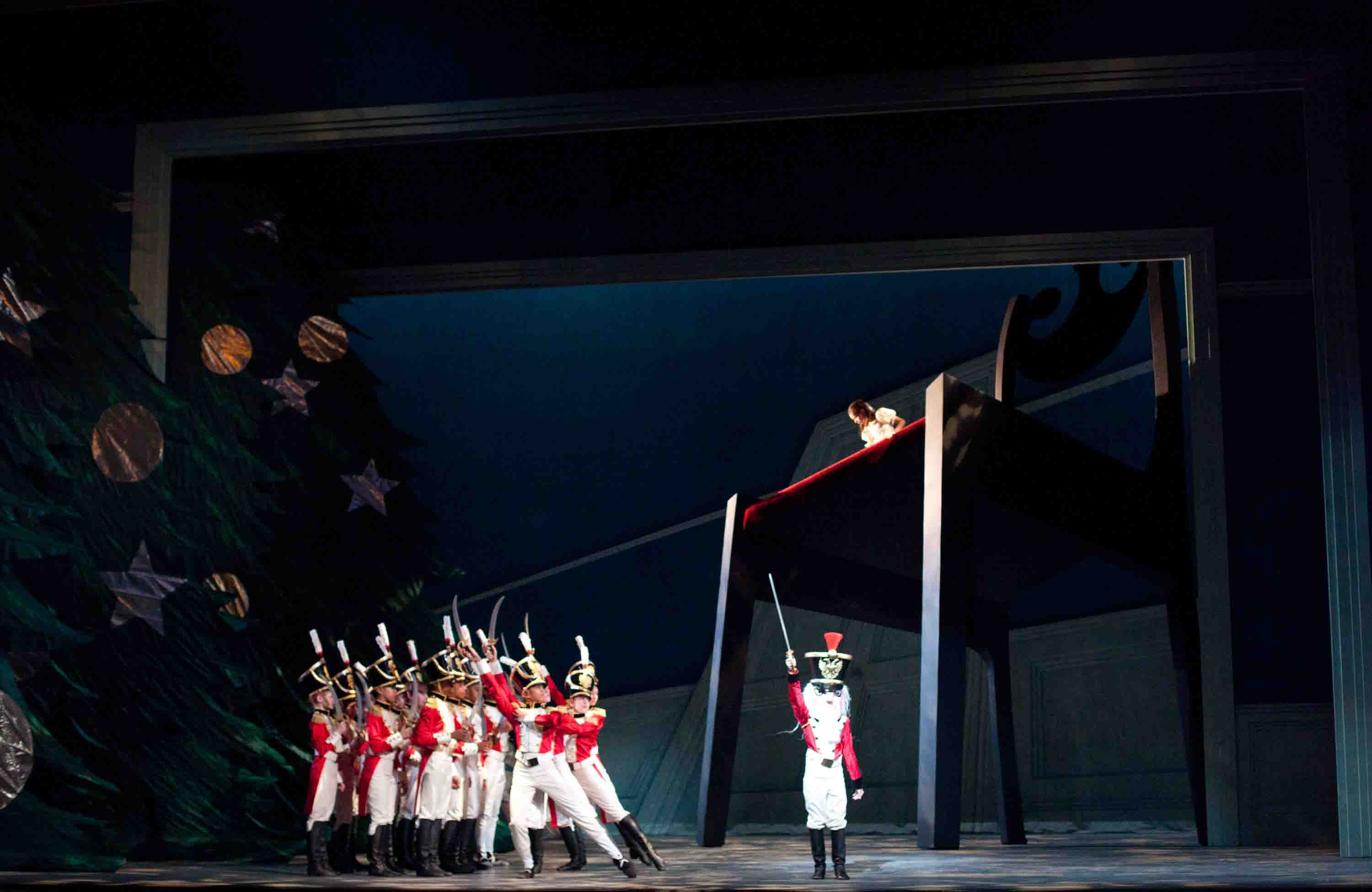

Gotcha: Justin Souriau-Levine as Little Mouse in Alexei Ratmansky's The Nutcracker for American Ballet Theatre

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

Ratmansky's version of The Nutcracker for ABT comes after two earlier tries, first with the Kirov Ballet and then with the Royal Danish Ballet. On both occasions the stakes were against him, primarily through having his creative freedom thwarted by a designer's wishes or by his having to work with already prepared designs. His latest effort, given its official premiere on December 23, contains so much that's insightful and charming, I'd like to say "third time lucky." In truth, this production will take time to cohere.

Some points--beginning with what's actually happening to the young heroine, Clara, in reality and in her imagination--need to be reconsidered and resolved. Other passages simply need further rehearsal and, more important, further performance to make them smoother and richer. And, if I had my way, the jokey stuff evidently put in to draw an audience of kids would also be toned down. None of its crass silliness--for example, the ballerina embodying the adult Clara playing peek-a-boo from the wings, as if animating her inner child--relates to the sophisticated sense of humor revealed in Ratmansky's other ballets.

Surely there's time for this fine-tuning to occur. ABT has an agreement with BAM to expand its Nutcracker season annually, over five years. Since The Nutcracker, in myriad permutations, has proved to be a surefire money-maker and the company needs to make good on its $5 million investment in the production, presumably all that's necessary is patience and hard work. Of course the future holds one additional budget item: The many children in the cast will outgrow their roles in less than two years, requiring successors to be coached from scratch.

What sort of Nutcracker has Ratmansky given us? He's positioned himself--comfortably, I think--between the old and the new. His version doesn't have the look of fond loyalty to the past--to the original, choreographed in 1892 by Lev Ivanov, according to the plan formulated by Marius Petipa--yet it's hardly a renegade version. Ratmansky has conceived his Nutcracker as the journey of a young girl who has not quite given up playing with dolls but has already begun to dream of romantic love (a little in fear, perhaps, of love's erotic dimension).

What will we find different from the 1954 Balanchine version, which has held sway for more than five and a half decades? A clue to the answer lies in the fact that Ratmansky thought the party scene at the home of a comfortably off family too long and tedious. So he co-opted some of its music and contrived a cute kitchen scene to open his show and introduce many of the main characters, including those of the rodent persuasion. As a result, his party scene is superficial, without any subtext of relationships among the generations or of manners understood as morality.

My Hero! Catherine Hurlin (above), Tyler Maloney (below), and additional students from American Ballet Theatre's Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School in Alexei Ratmansky's The Nutcracker

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

The appearance of the strange Drosselmeyer (ostensibly Clara's godfather, though the program doesn't say so); Drosselmeyer's gift to Clara of a doll-size Nutcracker; the jealous kid brother Fritz breaking it and Clara succoring it; the thrilling yet ominous transformation scene in which objects and living creatures change their relative size; the battle between the invading mice and the toy soldiers; and Drosselmeyer's role as perpetrator of these dark wonders--none of this diverges inordinately from what we're used to. Except that Ratmansky, with the best of socio-political motivations, makes Clara the one who brings down the nasty Mouse King, not just a helper in this surely justified assassination. Unfortunately this leaves the Nutcracker Boy (the shell-crunching toy now Clara's size and human) looking like something of a wimp.

For the Snow scene, Ratmansky thought back to the real Russian winters he had experienced in his youth, where a driving storm could kill. He puts Clara and the Nutcracker Boy in real danger, then has Drosselmeyer rescue the shivering, disoriented children in a sleigh and guide them to the Land of Sweets.

Candyland turns out to be puzzling, sort of a Persian Paradise, with a Sugarplum Fairy who has a mere walking role: hostess-with-the-mostest. According to tradition, the wonders of this kingdom are presented in a series of self-contained dances evoking exotic domains from which goodies emanate. These are duly tackled, and Ratmansky has great fun with them, making a show of his cleverness to which you gradually succumb. The best of them is the hilarious "Arabians" (worthy of a PG rating, not that anyone paid any heed), a quintet for four voluptuous harem women and their "husband." While the femmes, the irresistible epitome of Lust Lite, vie for the guy's affections, they are a united in their assurance that his pompous attitude of power over them is ridiculous.

The "Waltz of the Flowers" is duly performed, but marred, I'd contend, by a quartet of male bees buzzing around all that irresistible pulchritude and daringly tossing every last bloom across a good bit of space from one "pollinator" to another. Perhaps only the traditional Dewdrop should be allowed to appear amongst the blossoms, because she complements them, her virtuosity lending sparkle to their lush romantic style.

The Snow scene of Act I was undermined in a similar way, with Ratmansky introducing a vision of a grown-up Clara and the Nutcracker Boy as Princess and Prince in the whitened forest just before the snowfall starts in earnest and then, taking a leaf out of Hans Christian Andersen's book, has the snowflakes themselves torment the children. Both instances are clearly occasions in which a magnificent ensemble is meant to function alone, as a collective--and major--character in the ballet. It's odd that Ratmansky, who has an ingenious gift for group patterning, should have put these obstacles in his way.

With This Ring: Gillian Murphy as Clara, The Princess, and David Hallberg as Nutcracker, The Prince

Photo: Gene Schiavone

On the common philosophy that all good things must come to an end, Ratmansky gives us an epilogue that returns Clara to her bed back home, hoping he's persuaded the audience to join Keats in wondering "Was it a vision, or a waking dream? / Fled is that music:--Do I wake or sleep?"

I'm willing to go along with the whole business provided that Ratmansky takes a long, calm look at what he's created and makes some of the adjustments that will move his ballet above and beyond the category of Lively Entertainment. If he can't or won't, I'll settle for being entertained--by his intelligence, his understanding of human nature, his knowledge and love of dance history, and his flair for the unexpected.

Children--some 30 of them at each performance--dominate the cast of this Nutcracker and they do themselves and their academy proud. They're all students of ABT'S Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School and seemed more technically accomplished in this production than the pupils I last saw in one of the school's demonstrations. Even more important for the occasion, they were natural and ebullient; some of them--Kai Monroe as Fritz, the naughty kid brother, and Justin Souriau-Levine as the Little Mouse, for instance--perform as if born for the stage.

As the Nutcracker Boy, Tyler Maloney evoked, perhaps inadvertently, some of the pathos of a youngster aiming for an authority that's still beyond him. He was also inexplicably underserved by whoever coached him in the famous mime monologue in which he recounts his adventures-to-date upon his arrival with Clara in the Kingdom of Sweets.

The 14-year-old Catherine Hurlin, who is clearly the heroine of the show, was strangely perfect as the young Clara. Her movement was impeccably balletic when called for, unaffected and vivid at more pedestrian moments. Her every gesture and facial expression corresponded truthfully, phrase by phrase, to her character's situation at the moment. Her teachers and coaches must have found her a phenomenon to work with. And yet, though I admired her performance, she never moved me. Everything she did, no matter how apt and beautifully executed, seemed to me taught rather than true.

As for the adult dancers . . . The grand pas de deux, originally for the Sugarplum Fairy and her Cavalier, complete with Sugarplum's solo to the otherworldly music for the celesta, has, as I've said, been reassigned to a pair of characters called Clara, The Princess, and Nutcracker, The Prince. They are manifestations of the beautiful adults that the ballet's child protagonists (young Clara, at least) dream of becoming when they grow up. Although their duet climaxes the ballet, with many a delicious rethinking of the traditional steps, as visions they somehow seem only belatedly relevant to the proceedings.

On opening night Gillian Murphy did quite well, considering the fact that the solo, in particular, doesn't suit her greatest virtues--power, a star athlete's exactitude, and a burgeoning dramatic gift. David Hallberg was in his element--a marvel of technical acumen operating with cool elegance. As for Drosselmeyer, the veteran dramatic dancer Victor Barbee still has to figure out who and what he wants this mysterious character to be.

Richard Hudson's set designs and costumes play a significant role in the production--and often threaten to overwhelm it. While the chaste dresses for Clara and the other little girls at the Christmas Eve party are lovely, those for most of the inhabitants of the Persian Paradise that the Land of Sweets has become have more than a touch of Vegas about them. Granted, the brash colors and color combinations, aggressive patterns, and over-elaborate ornamentation are fun for a while. Eventually, though, they exhaust the eye and call to mind the taste of the nouveau riche.

The sets fare better, perhaps because they help tell the story. A front cloth, on view while the overture is played, shows a trim upper-middle-class house of yesteryear--tipped sideways to stand nonchalantly on one of its corners. The image indicates that what ensues will interlace prosaic reality and the realm of the imagination (and its accompanying dangers). As Tchaikovsky's scene-setting music winds down, light pours through one of the upstairs windows. Then, at the party scene, a doll-house that replicates, three-dimensionally, the one painted on the front cloth is presented to Clara as a special Christmas gift. The closing passage of the ballet takes us inside the "real," human-size house to the girl's bedroom where, just behind the window we first saw illuminated, Clara now goes to sleep--secure and happy, cuddling her Nutcracker doll.

Another fine bit of scenic wonder arrives when--thanks to a magical transformation in size--a gargantuan chair appears. Perching on it, and looking down on the battle between the marauding mice and the toy soldiers marshaled by the Nutcracker Boy, Clara seems to be little more than a foot high. Nevertheless she goes from one anguished pose to another and, finally, removing one of her slippers and taking careful aim despite her distress, she exterminates the seven-headed Mouse King who is about to vanquish her beloved Nutcracker. The ominous look of the Brobdingnagian chair itself and the skewed perspective of this scene struck me as echoing a haunting modern-day children's book by Chris Van Allsburg, The Mysteries of Harris Burdick. (To see the images in this book, click here. See--and click on to enlarge--the pictures for "Archie Smith, Boy Wonder," "Missing in Venice," "The Seven Chairs," and, especially, "The House on Maple Street.")

Two for the Show: Veronika Part as Clara, The Princess, and Marcelo Gomes as Nutcracker, The Prince

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Coda: I went back to BAM, despite the Holiday Blizzard of 2010, to see Veronika Part and Marcelo Gomes dance the leading grown-up roles. Gomes chose to be the recessive partner here. His technical prowess, delivered in his inimitable panther-on-the-prowl style, was present but subdued. Here, a man who can play villains and danseurs nobles alike was an ideal romantic suitor, his tenderness toward his ballerina providing a constant subtle support that made her look like a goddess.

Part was, quite simply, glorious. Dancing with the long, sensuous phrasing that suits her best, she even gave whiplash feats like supported multiple pirouettes a sensuous legato look (just as, a few minutes later, she would make the celesta solo aptly tiny and delicate, but still lusciously soft). Falling backwards from her prince's embrace, she seemed to swoon. Towards the end of the adagio, a complexity of feelings appeared to swirl through her, as if she were recalling the emotions of the girl she once was and, despite natural reservations and fears, accepting the joys of womanhood.

Throughout this performance Part looked utterly confident, the self-doubt that has often plagued her banished. A Russian beauty with an air of high nobility, she even broke out from time to time into a genuine America's Sweetheart smile. Performances like this make you believe that, despite the well-grounded warnings of the pessimists, ballet is not ready to die just now.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary