Seeing Things: November 2010 Archives

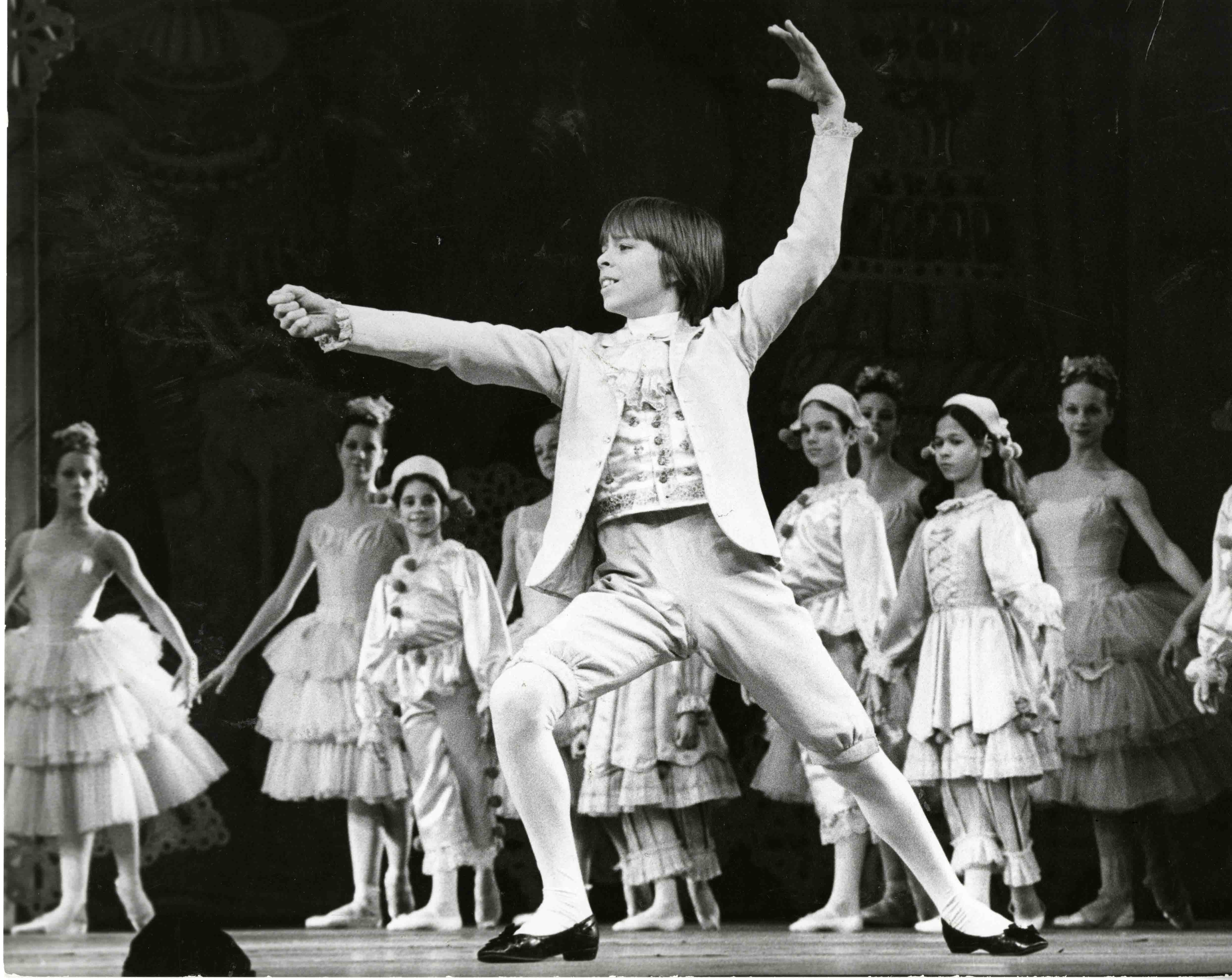

Dancer unidentified

Photo: Martha Swope (1964)

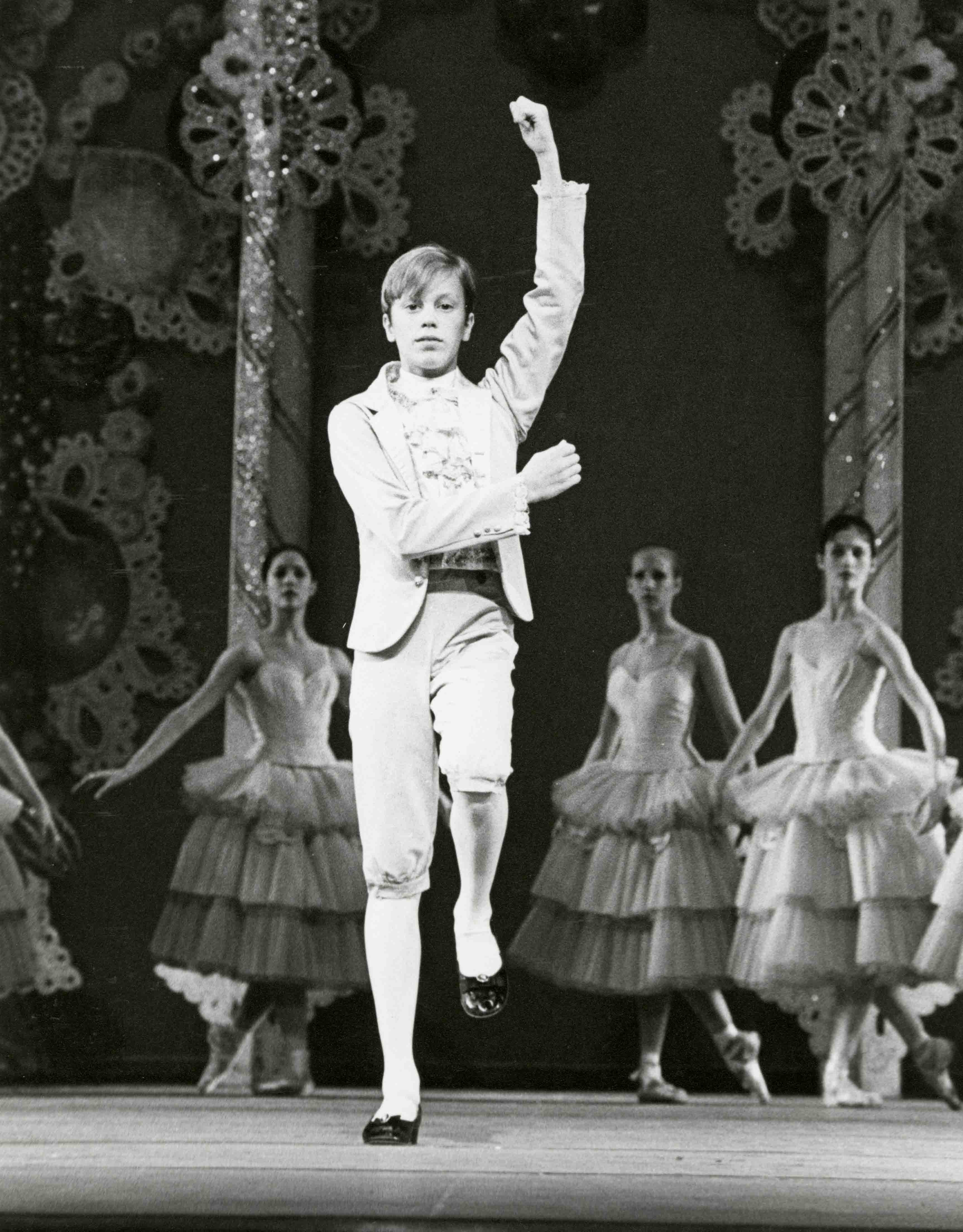

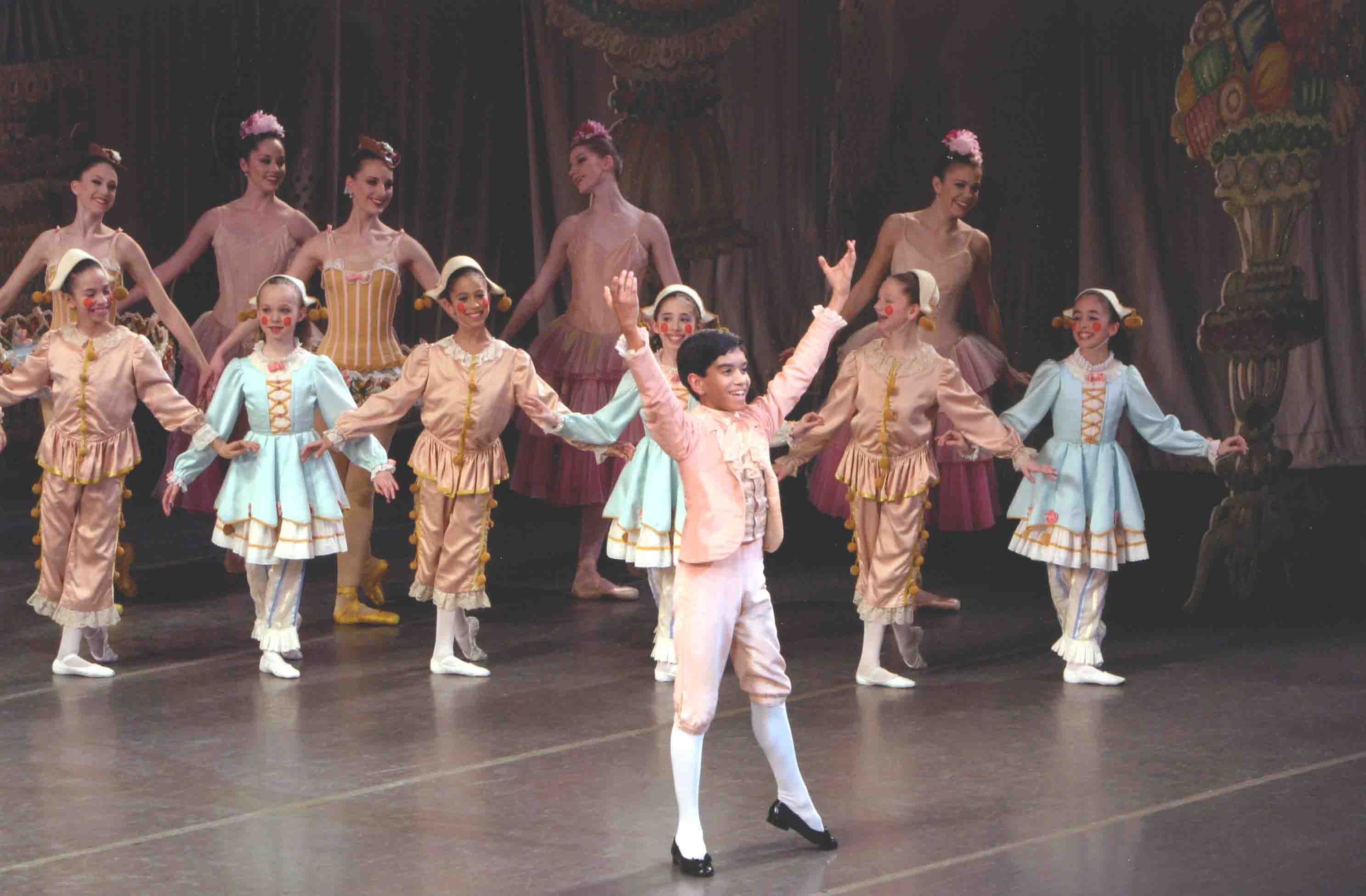

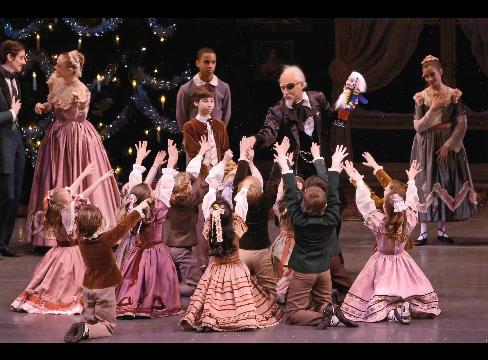

Note: The photos of the young Prince reproduced here are from George Balanchine's celebrated version of The Nutcracker, inspired by the Russian production of his youth. Balanchine himself played the role as a student in the St. Petersburg academy that trained dancers for the celebrated company we now know as the Kirov or Maryinsky Ballet. Each photo shows the Prince in the mime monologue with which he tells the Sugar Plum Fairy about his earlier battle with the Mouse King and his retinue. Balanchine himself often coached the School of American Ballet student assigned the role.

Dancer: Christopher d'Amboise

Photo: Martha Swope (1972)

November's rolling along toward December and the Winter Solstice, it's already twilight by four o'clock, and the news of the world is not good. In these dark times (both literal and figurative), people--at least those who still have jobs and roofs over their heads--are inclined to indulge in frenzied bouts of shopping and preparations for gastronomic bravura as they anticipate "the holidays."

Mercifully, the hectic tempo of the season is soothed now and then by seasonally appropriate thoughts--even deeds--of good will to all men (and women, of course) and by visions of an alternate world offered by theatrical performance. Here's where The Nutcracker comes in, being a ballet that depicts Christmas in both its domestic and magical guise and lets us see it through childhood's unfettered imagination.

Dancer: Peter Boal

Photo: Martha Swope (late 1970s)

Many a version of this venerable ballet exists, varying the era and the locale or culture of the original (Victorian period; upper-middle-class) or, more radically, changing the very concept of the work. The original Nutcracker ballet, created in Russia in 1892 by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, was based on E.T.A. Hoffmann's intriguing tale The Nutcracker and the Mouse King (1816). Its music, commissioned from Tchaikovsky, is one of the Western world's most evocative scores.

Dancer: Avi Scher

Photo: Paul Kolnik (1996)

Beginning with George Balanchine's definitive version of The Nutcracker, choreographed for the New York City Ballet in 1954, the work has gradually become--at least in the States--an annual destination for holiday-minded viewers and a cash cow that saves the company producing it from financial ruin. People who couldn't care less about ballet enjoy The Nutcracker; susceptible children are inspired by seeing it to clamor for dance lessons; and experts in the field never tire of mining outstanding productions of it for new sources of delight and new meanings. The most faithful Nutcracker viewer I've known, the late Edward Gorey, a notable author-artist with a pronounced penchant for classical dancing, told me that he attended every performance, year after year, of the City Ballet's production, which typically runs for eight or nine performances a week, for five weeks.

Dancer: Gregory Malek-Jones

Photo: Paul Kolnik (2004)

In a four-part series under the umbrella title "Winter Solstice," I'll be writing about three of the many Nutcracker productions here in New York, one by one. There are several other local versions worth viewing--and I've seen some of them in previous years--but the ones I've chosen for this venture seem to me the ones likely to reach the widest audience. They are:

The Nutcracker / Choreographer: George Balanchine (1954) / New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center / November 26, 2010 - January 2, 2011

The Hard Nut / Choreographer: Mark Morris (1991) / Mark Morris Dance Group / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House / December 10 - 19

The Nutcracker / Choreographer: Alexei Ratmansky (world premiere) / American Ballet Theatre / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House / December 22, 2010 - January 2, 2011

Dancer: Lance Chantiles-Wertz

Photo: Paul Kolnik (2009)

Meanwhile, I offer below some of my earlier thoughts about the Balanchine Nutcracker.

THREE ARTICLES ON BALANCHINE'S NUTCRACKER:

The essay below was first posted on Voice of Dance, November 26, 2008.

Thoughts on Balanchine's Nutcracker

New York City Ballet: George Balanchine's The Nutcracker

New York State Theater, NYC

November 28, 2008 - January 3, 2009

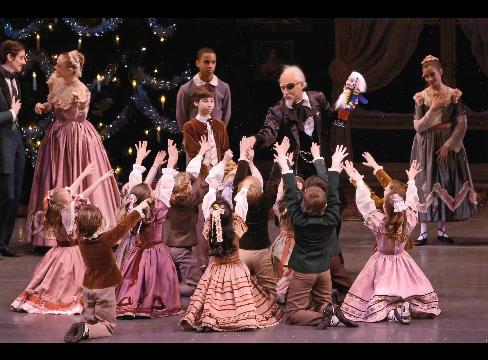

New York City Ballet's The Nutcracker with Robert La Fosse as Herr Drosselmeier. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

Yes, we--believers and doubters alike--take our children, grandchildren, and godchildren to see the New York City Ballet dance George Balanchine's version of The Nutcracker, created in 1954 and an annual Christmastide event ever since. Many youngsters also dance in it, if they're being trained at the School of American Ballet, the company's rigorous academy. But this ballet is in no way mere kiddie fare. It offers the adult much food for thought--and reverie.

After Tchaikovsky's celestial overture--during which we gaze at a front drop showing an angel spreading starlight over the snow-covered roofs of a gemütlich German town some 200 years ago--we get our first glimpse of a pair of children gazing with unquenchable curiosity at a world from which, for one good reason or other, they have been excluded. Marie and her rambunctious kid brother peer through the keyhole into the drawing room where their parents are putting the finishing touches on the massive candlelit Christmas tree and arranging the presents destined for the children and their young cousins and friends who are about to arrive. The firmly shut door means "Children, you may not look--yet."

The ensuing party is a lively one, tamed by the grace of formal social dancing in which three generations join and the examples of civilized adult manners, along with friendly admonitions to over-boisterous youngsters. It harbors areas of mystery, too. They center on the presence of the elderly, eccentric Godfather Drosselmeier (accompanied by a solemn handsome nephew just a few years older than Marie and the rough-and-tumble boys at the festivities).

Drosselmeier seems capable of magical feats far more complex than the scarf tricks with which he first entertains the children. An ingenious inventor of mechanical toys, he has fashioned adult-size wind-up dolls and, especially for Marie, whose fancy it captures immediately, a foot-high working nutcracker in soldier's garb. But then her overexcited, jealous little brother seizes it and dashes it to the floor so that its jaws, with their prominent teeth, can no longer crack nuts to deliver their sweet kernels.

When the party ends, as all parties must, and the guests have departed, Marie reappears in the deserted drawing room in her angelic nightclothes. She has left her bed to succor her beloved Nutcracker. The young girl--a tiny, fragile figure in the large, silent room--peers through its French windows at the wintry midnight townscape, but it is too dark to make anything out. It's a lonely moment, and she comforts herself by curling up on the sofa, cradling her broken treasure.

School of American Ballet students in New York City Ballet's The Nutcracker. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

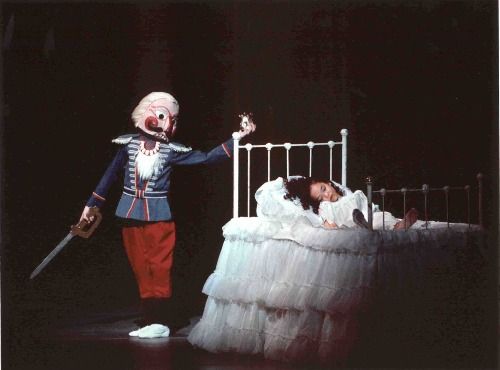

Now vivid clues to more frightening, perhaps evil, aspects of life are introduced into Marie's home--in which she is used to being cosseted with love, creature comforts, and safety--seemingly because the prepubescent girl is getting old enough to come face to face with a few threatening adult realities. Under the cover of night, Godfather Drosselmeier returns, mends the Nutcracker for the child he clearly adores, displays its face beside his own as if to point out a resemblance--and conjures up an army of mice.

More and more, as the decades have slipped by, the rodents--the king with seven heads, each crowned, his rodent family and friends, and a bevy of rodent offspring (a grotesque parallel to the human guests at the Christmas Eve party?)--have made the ensuing scene of the battle with the mice more comic than scary, a pity, I think; the balance was more effective when it went the opposite way.

Marie awakens to witness startling transformations. The Christmas tree grows to gargantuan size. The toy soldiers, neatly arranged in a case in the drawing room grow to her own height and come to life to battle the mice. The bed that Drosselmeier's nephew earlier offered Marie for her broken Nutcracker magically scoots away as if of its own volition to be replaced by a life-size bed, and the Nutcracker, now grown as well, charges into battle to protect the terrified Marie. The changes of size and awakening to new powers hint at the physical and emotional processes of puberty, during which a child can seem to grow in body and soul overnight.

It is through the mice's invasion, though, that Marie's mettle is tested. The valiant Nutcracker is responsible for the necessary swordplay, but when it looks as if he may be defeated, Marie has the courage and the presence of mind to distract the Mouse King by throwing her slipper at him, so the prince can get the upper hand, slaughter the royal rodent, and hold aloft one of its seven golden crowns. (The boy will give Marie full credit for her bravery in recounting the event to the Sugar Plum Fairy in Act II--in a pantomime solo Balanchine himself performed as a ballet student at Russia's renowned Maryinsky Theatre.)

Meanwhile, again as if by magic, the Nutcracker is stripped in the blink of an eye of his soldier outfit to reveal the elegant costume of a storybook princeling. With immaculate chivalry, he presents the tiny, gleaming crown to Marie and leads her out into the landscape she only peered at through the window earlier, it being imperceptible to her while she was a child sheltered in her own home. The scene they traverse is a forest swept by falling snow, with (human) snowflakes whirling through it, as if wafted by the wind. This is the realm of unmarred nature in which events once conjured up only by the imagination are now really about to take place.

At the Christmas party, we also witness Marie's early lessons in love, first when she cuddles her Nutcracker while her little cousins and girlfriends rock the dolls they've received as presents, then when she solemnly shakes the hand of Drosselmeier's nephew, to thank him for bringing her the miniature bed in which her injured Nutcracker can repose. Lastly, once the other guests have left for home, the boy escorted away by his uncle, the girl led off to bed in the opposite direction by her mother on a darkening stage, each of the youngsters extends a yearning arm toward the other, as if to promise that the bond beginning to form between them will not be broken.

New York City Ballet's The Nutcracker. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

In Act II, when Marie and the Nutcracker Prince find themselves in the Kingdom of Sweets ruled over by the Sugar Plum Fairy, we've entered the domain of imagination given free rein. In one way it's an homage to the ingenuous childish dream of possessing the full spectrum of deliciousness. In another, it contains a moral: the youngsters are being rewarded for mature, adroit behavior in their encounter with the marauding mice. Balanchine, as he said on another occasion, is having his cake and eating it.

Sweets from all corners of the universe are presented to the regally enthroned children and dance for them--candy canes, marzipan shepherdesses, hot chocolate--each according to its kind. Eventually, though, it's time for Marie and her young prince to return to ordinary life, albeit in a magical sleigh pulled by reindeer that fly through the air. Imagination has been given its due and the youngsters have had their vision of pleasure which will no doubt sustain them throughout their lives, but there may be some relief, too, in returning to the familiarity of the commonplace.

Balanchine teaches many a lesson in The Nutcracker but doesn't press any of them upon the spectator. They are simply there to be ferreted out or absorbed unconsciously, and all the more intriguing for that. For example, the choreographer uses children of different ages (giving each group dance material within its capabilities, which is then brilliantly executed), fully professional adult dancers of varying ranks, company apprentices in walk-ons, and a few senior artists in character roles. In this way, Balanchine shows how a dancer usually begins as an absurdly young child and then (if the will and the body hold fast and luck blesses the enterprise) progresses, stage by hard-worn stage, in his exacting trade.

Balanchine's Nutcracker is also a treatise on the nature of reality and illusion--and a child's uncanny ability to live in both worlds, moving fluidly between them. In the more rigidly compartmentalized adult world, this is a gift most often retained by artists.

© VoiceofDance.com 2008

The following piece was first posted on SEEING THINGS, November 27, 2003

A "Nutcracker" Anecdote

New York City Ballet: The Nutcracker / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / November 28, 2003 - January 4, 2004

The Nutcracker, in George Balanchine's (for me) definitive version, danced by the New York City Ballet, opens November 28 at the New York State Theater for a run of six weeks. I know it well, not just as a dance critic but also as a one-time ballet mother whose School of American Ballet-attending child was for several years a member of the show's huge cast of kids.

The Nutcracker, in George Balanchine's (for me) definitive version, danced by the New York City Ballet, opens November 28 at the New York State Theater for a run of six weeks. I know it well, not just as a dance critic but also as a one-time ballet mother whose School of American Ballet-attending child was for several years a member of the show's huge cast of kids.

In this latter guise--conveyer of child to endless rehearsals--I, along with the other moms, dads, and nannies, occasionally got to watch a stage run-through. I remember in particular a dress rehearsal supervised by Mr. B himself. Decades later, it still provides me with a clue to the great man's sensibility. On this occasion, matters had worked around to the point where Marie, the ballet's juvenile heroine, terrified by the attack of the predatory mice, flees to a white-ruffled bed, stands on it for a moment, all innocence and vulnerability in her little white nightdress, then tumbles backward in a faint.

Her fall looked fine, albeit a little smudged, to me, but Balanchine wasn't satisfied. He asked that she repeat it and was no happier with the result. He went up to her and, with typical gentle courtesy, worked directly with her--quietly and intimately, as if the two of them were alone on the stage--explaining and showing what he wanted. Then he stood back as she tried again. It was still not right in Balanchine's eyes. Turning from her so that she didn't see his little twitch of impatience and exasperation, he addressed the children's ballet master and the other assistants in attendance: "Somebody teach her how to faint."

How to bow, how to faint, how to waltz. Over years of mere glimpses of Balanchine at work and many an interview with his dancers, I came to understand that these skills were as important to the choreographer as a breathtaking mastery of the classical dance vocabulary he did so much to advance. I think it disturbed him at the core when dancers (even child dancers, because they represented his art's future) couldn't execute convincingly the moves that any citizen of civilization can perform almost instinctively. Balanchine, as his work reveals, gloried in the high artifice of ballet, but he never divorced his art from human nature.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: George Balanchine's Nutcracker

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

The following review was first posted in the Culture section of Bloomberg News, November 29, 2007.

City Ballet's Annual 'Nutcracker' Defies Gravity

Robert La Fosse, standing second from the right, as Herr Drosselmeier, performs in the New York City Ballet production "The Nutcracker" in New York in this undated photo. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

Nov. 29 (Bloomberg) -- A bracing tonic for the Scrooges among us is "The Nutcracker,'' choreographed to Tchaikovsky's captivating score by George Balanchine for the New York City Ballet.

In the course of its annual five-week run at the New York State Theater (this year, through Dec. 30), it regularly features the company's seasoned stars as well as stars-in-the making; alternating casts of some 40 Lilliputian children from the School of American Ballet, impeccably rehearsed by Garielle Whittle; and scenic wonders such as a Christmas tree that grows to a surreal height, lights flickering.

You know the story: At a decorous Christmas Eve party long ago, Godfather Drosselmeier gives Marie, the prepubescent daughter of the house, a magical nutcracker that sets in motion striking transformations and wish fulfillments. These climax in a visit to the Sugar Plum Fairy, who reigns over the Land of Sweets, with Marie escorted by the nutcracker now transmuted into the young prince of her girlish dreams.

The opening night's Sugar Plum Fairy, Maria Kowroski, mistress of adagio dancing, gave a ravishing account of the ballet's climactic duet. Her Cavalier, Charles Askegard, was secure enough to toss her into the air for a moment midway through their fish-dive maneuver that is already a tour de force: "Look, Sugar, no hands!''

Maria Kowroski as the Sugar Plum Fairy, rear, and Charles Askegard as her Cavalier, perform in the New York City Ballet production "The Nutcracker" in New York in this undated photo. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

More surprisingly, Kowroski was radiant and tender at her entrance, reigning over the flock of tiny angels that scoots across the stage in interweaving patterns as if on ball bearings.

Ashley Bouder, as the Dewdrop leaping and whirling her way through a corps of Flowers, was even more astounding than usual in her athletic brilliance. Audiences adore her. I still have reservations about her dancing, which is two-dimensional rather than sculptural, a phenomenon that a camera could render perfectly. Live dancing demands more depth.

I also miss the whiff of tragedy that Heather Watts once brought to this role, as if to reflect the evanescence of a dewdrop's perfection. But perhaps that is too much to ask these days when bravura technique is valued above subtler qualities.

The generation of nascent ballerinas was represented by Erica Pereira and Rachel Piskin, not long out of their student years at SAB. They seconded the remarkable young virtuoso Daniel Ulbricht in the shamelessly politically incorrect pseudo-Chinese dance, "Tea,'' which represents one of the treats displayed in the second act's "Land of Sweets.''

Among the children in leading roles, Jonathan Alexander stood out for his spontaneous exuberance as the naughty kid brother. The all-important character role of Herr Drosselmeier lies at the other end of the age scale. Playing the enigmatic inventor and magician who makes Marie's dreams (as well as the nightmares) come true, Robert La Fosse has toned down his earlier over-the-top interpretation. Now he displays just the right blending of strangeness and fantasy.

Through Dec. 30 at the New York State Theater, Lincoln Center. Information: +1-212-870-5570; http://www.nycballet.com.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved.

My mother must have had a decent command of French. Sometimes, as I was growing up, she'd refer to it, though always briefly and casually, as if the subject had little importance. All I ever found out was that she had taught elementary--perhaps even intermediate--French as well as English literature (using a textbook called From Beowulf to Thomas Hardy) at New Utrecht High School in Brooklyn in the 1930s. That was before my father and then I came into her life and changed her career to that of housewife and mother.

But she had kept some of the French textbooks she used (which, since her death, I harbor for nostalgia's sake) and in our basement two deep drawers of a rickety bureau were crammed with several hundred unused picture postcards displaying French "places of interest." I wanted to ask her, but couldn't : Did she have no time to put the postcards in order? Would looking at each of them be a series of stabs to her heart? Could it be possible that she didn't care anymore about the sites they showed?

More evidence: When I was very young, my mother would often lie on the living room couch for an hour in the late afternoon, reading (she was an indefatigable reader), as she rested between sieges of her household labors, which included assisting my father with his medical practice--conducted under our roof--as nurse, receptionist, and cleaner. If I wandered through the living room during this repose, she would occasionally, like a kindly sergeant, fond of his youngest, least experienced cadet, issue a simple command in French that I would rush to fulfill, as if the foreign language turned it into a critical military mission. She taught me what her "orders" meant and I memorized the meanings swiftly. The only command I still remember was "Apportez-moi un verre d'eau, s'il vous plaît." (Bring me a glass of water, please.) I assume now that she used the formal rather than the familiar you to enhance the gravity of the errand.

You might say that these French "lessons" were trivial, but I think not. They planted the seed.

My formal study of French, if it can be called that, began in junior high school, with a Miss Brenner. I assumed she was American, because her French accent was atrocious. That was obvious even if you didn't have a lot to go by. She spoke in a dreary nasal monotone and if she had a love of French or a sense of excitement about learning it she kept these feelings at home. My first few months under her tutelage were a nightmare because I couldn't rid myself of my idée fixe that there was an exact French equivalent for every English word, so that one need only memorize several thousand of these equivalents and arrange the foreign words in the same order as one did the words in one's mother tongue. It was my own mother who gently disabused me of this naïveté and, in the process, enhanced my sense of wonder about foreign languages. French and all the others did not comprise single words set in a universally observed pattern, but a unique manner of speaking, even a way of thinking.

I managed to get through my two years with Miss Brenner with my attraction to French intact and moved on to Samuel J. Tilden High School, where I worked my way up to the most advanced (not very) course in French given by a Dr. Schwartzback. He was a coarse-voiced, grumpy guy of a certain age who didn't seem to have much more enthusiasm for French (or, for that matter, teaching) than Miss Brenner did. I discovered recently that he grew up speaking German and earned his living teaching it when he emigrated to the United States. Because of the American anti-German sentiment generated by World War II, he was forced to pursue his career instructing Brooklyn adolescents in French. All I recall from the year I studied with him was a far closer reading of Cyrano de Bergerac than that play deserves. At graduation, I was awarded the French medal--on qualifications that, today, a mere month of diligent work with Rosetta Stone could easily surpass.

Still, once I started college, French remained my language of choice. Why, I'm not sure. Perhaps because of my mother's affection for the language and its culture, which was, apparently, largely fostered by her recollection of a summer of study abroad before she married. She did nothing to further her fondness for the land or its lingo, apart from luring me into its pursuit with a few sentences gorgeously pronounced and helping me realize that a foreign language was a world of its own. Or perhaps I remained steadfastly attracted to French because so many aspects of its culture were held to be the acme of glamour at the time, and glamour proved a powerful magnet to me in my innocent youth. I confess that, even today, it exerts its pull.

The college placement exam for French, however, was nearly my undoing. I'd chosen to attend Barnard, the all-women's undergraduate division of Columbia University, mostly because it was in New York, which I knew and loved as an artistic mecca. Barnard was a member of the Seven Sisters, the equivalent of the Ivy League, presumably the top-ranked of the country's men's colleges (gender segregation still being rampant in the fifties). Because of its exalted position, Barnard refused to depend on the evaluation of the heterogeneous assortment of high schools its first-year students came from and certainly didn't think of asking the students themselves what level they thought suited the modest skills they had acquired thus far. I was certain I belonged in third-year French, which would have had me reviewing and extending my abilities in matters of grammar and vocabulary, while challenging me with brief, reasonably accessible passages from the literature for which France is rightly celebrated. But no.

My grade in the exam probably fell on the cusp or just a point or two over it into the next level--"French Literature from the Middle Ages to the Present," or some such title. This was a year-long survey course that, if you survived it, qualified you to study in depth each of the centuries and significant literary movements it covered all too swiftly. Since I had no expectation of surviving it, though, I didn't worry about the future, only the present, which seemed to me hopeless.

The instructor was a Mme. de Wyzewa, a frail-looking elderly woman, with an equally frail voice. For 50 minutes, three mornings a week, she stood before us and lectured in her native language, barely audible but with razor-sharp diction, occasionally turning to scrawl a hard-to-spell author's name or some birth and death dates on the dusty blackboard behind her. Everything about her--her pinched face, her wispy grey hair, her faint voice, her shaky handwriting, even the passing hints she exuded of formidable erudition--seemed made from chalk dust. More disconcerting than this ghostliness (which I now see as a mix of pathos and dignity) was the fact that I didn't understand a single word she said. Today, a student with this problem would stride into the office of the French Department and insist upon being dropped a level, into a world of comprehension. Not then. In my undergraduate days, the domain of teaching was ruled by professors and administrators. A student had little or no say.

My solution was to scribble phonetically every word I could make out at the lectures. Then, in the course of the day I would--usually in the company of my dear friend Helen, who shared my plight and response--spend nearly two hours trying to make sense of our phonetic scribblings. (Helen's face, capable of launching a thousand ships, did nothing for her here.) Suddenly, however, after six weeks of our absurd, frustrating labors, in a flash, we understood everything, even the subtleties our elusive professor had been trying to impart. The light had dawned and we loved French forever. I can't understand how or why this happened, but I don't care. Perhaps the magical illumination was a miracle. We certainly needed one.

Although I was officially a writing major in Barnard's English Department, I made sure to spend plenty of time in the quarters of the French Department, just hanging out to exercise my spoken French (preferably while smoking Gauloises) and taking courses with a number of the instructors. The professor who made the strongest impression on me was Renée Kohn, a native Parisian who was doing a decade-long stint in New York.

Students, especially young impressionable ones, are extra-sensitive to how their teachers look. Barely a decade younger than Mme. Kohn, my classmates and I easily fell prey to her particular beauty. She combined a modest version of the sophistication that French women seem to be born with and the luminous innocence of a child. Small and slender, she'd brush off any praise of her figure that the bolder girls might offer privately with, "Oh, but I'm not like you Americans, with your beautiful legs." She had a point. I think that several of us who studied ballet gave her cause--not for envy, but for longing.

Her long hair was worthy of a Renaissance princess and accordingly a legend in the college. She wore it in one thick braid that she pinned (not a pin showing, naturally) over her head like a coronet. Rumor had it that, if she left her hair unbound, she could sit on it, which, as I discovered much later, was so.

If you praised her as a teacher, she'd brush off the compliment as if she truly believed she didn't earn it, laughing a little and saying, "Oh, It's just my hands. I guess I move them a lot, and my students think they're graceful."

In truth, she was a memorable teacher but not one of those stellar professors whose insights pierce your brain like an electric shock. What she gave us was essentially her love and admiration for the literature she shared with us. Many of us, stirred by the deep feeling she had for her subject, pored over the texts she assigned so that we could discover the source of her delight and, eventually, cultivate our own.

In a one-on-one conference, she was the epitome of empathy, without relinquishing her duty to correct you and to urge you, kindly but very seriously, to greater effort. Invariably she left you with the impression that it wasn't she who demanded the effort but the language and the literature themselves.

After I had graduated and she and her family moved back to Paris, we wrote to each other occasionally, then, as time went by, more often, and gradually we became friends.

The snobbery of the French--and of Parisians in particular--is legendary. Erik, a Danish colleague of mine, let me and my husband borrow his minuscule pied à terre in Paris for a couple of summery weeks when he wasn't using it. No matter that the sofa had to double as a pullout bed for two, which often startlingly snapped shut when we were asleep in it, and that the dining table served in off hours as a desk, being the only sizeable flat, firm surface in the place. No matter that the "shower" was not an enclosure but simply a shower head installed in the corner of the ceiling of a kitchen so tightly packed with culinary essentials that it was impossible for one of us to open the oven door to extract a roasting chicken at the critical moment while the other was bathing.

The enchantment of leading a primitive domestic life in these quarters was increased to sheer bliss by the fact that the apartment lay at the foot of one of the most ravishing and abundant open-air food markets in all of Paris. Because of it, we dined and picnicked luxuriously. I tried to conduct all my market transactions in French--for fruit and vegetables; seafood, chicken, and meat; butter, cheese, and pastry out of a fairy tale--letting my husband handle the money (to this day, I can't understand foreign money) and constantly forgetting that one kilo does not equal one pound but over two.

Having a temporary domestic base then gave us the notion that we should do our laundry at the local laundromat. So one morning, lugging our bundle of washing, we stopped off first at a tiny household-supplies store to buy the liquid detergent and fabric softener we'd need. The detergent transaction went fine; the small cluttered shop carrying the usual U.S. brands. The softener, though, nearly caused an incident in international relations.

I had looked up the word in Erik's French-English dictionary before leaving the apartment. I muttered it to myself all the way to the store and, once there, asked politely in French for some assouplissante. "Comment?" (What?) was the shopkeeper's reply, as if he had been addressed by an idiot. "De l'assouplissante, s'il vous plaÎt, monsieur," adding the "please" and the "sir" to help matters along. "Comment?" he repeated, his tone indicating that my request was utterly incomprehensible and possibly insulting. After a third round of the same, he raised a thick, grubby finger to his grizzled head as if the light had dawned, despite my incapability. "L'assouplissant!" he corrected fiercely. I had made the word feminine instead of masculine by mistakenly adding that final e that makes the t before it something you pronounce instead of dropping. In France, all nouns have a gender, even "fabric softener," which, for no reason I'll ever fathom, is a boy.

My confidence utterly shaken, but bravely continuing in my obviously imperfect French, I then asked the shopkeeper what we owed him, requesting him to write the sum down in numbers because, as I told him, my husband was in charge of the money and, hélas, did not speak French.

The French sense of the relationship between the sexes, which lags at least a century behind the times compared to the situation in many a developed land, has a certain charm, though it would certainly horrify most urban American women who identify as feminists. The French still echo the traditional belief that the man ranks higher than the woman by birthright; thus she is expected to defer to him. Interestingly, both genders tend to accept this assumption comfortably.

Here's my favorite example: As I've mentioned, the only flat, firm surface of any size in our borrowed apartment was the dining table/desk. When Erik turned over the keys to us, he pointed out a folder in the desk drawer that contained typed instruction sheets covering everything a guest might need to know about the place--in Danish, French, English, and (could it have been?) German versions. Erik was very generous, as I've said, and had an international bevy of friends who, like me and my husband, were deeply grateful for a place to stay on a visit to Paris.

Erik assumed, quite reasonably, that his clear, detailed written directions would suffice, but for some reason he emphasized aloud to us the fact that the table could be used for anything, since its surface was impervious. Today I realize he must have meant that, when the versatile piece of furniture was in dining mode, a fairly warm serving dish could be placed upon it without requiring a protective trivet. The surface imitated wood but was clearly in the resilient-plastic family.

One day I had an accident, spilling a large glass of red wine over the only really good dress (white, as fate would have it) I'd brought with me. Acting instantly--after all I was the daughter of a doctor and a seasoned housewife--I gave the garment first aid, beginning with, believe it or not, a rubbing with dampened salt, followed by soaking in cold, soapy water with a dash of bleach, then a thorough rinsing, wringing, and hanging out to dry on a sunlit clothesline. To my astonishment and relief, I had persuaded the stain to disappear.

But then, of course, the dress had to be ironed. A rummage through the kitchen cabinets produced an iron but not an ironing board, which would have taken up far too much space in Erik's compact dwelling. Using what I thought of as my ingenuity, I spread a large bath towel over the desk, laid my dress on top of it and blithely ironed away. I was about halfway done when my husband came back from a walk, took one look at what I was about, and said in his stern-warning voice, "Are you sure you can do that?"

"Oh, yes," I replied, with the slightly diminished confidence I was beginning to feel. "Erik said you could do anything on this table."

My husband relieved me of the iron and yanked dress and bath towel off the table in a single swift pull, looking for all the world like Brando with the tablecloth in Streetcar. Bared, the fake wood of the surface revealed what looked like large patches of sickly gray clouds. Boy, were we in trouble!

We hied ourselves to a nearby hole-in-the-wall shop that seemed to deal with wood finishing and the like. We said bonjour--the mandatory prelude to any French shopping transaction--to the proprietress, who, as I suspected, turned out to know almost no English. So I proceeded to lay the problem before her as best I could in French. Apparently the difficulty was judged to be a grave one because the well-padded woman with cropped hair, work shirt, denim overalls, and the sturdy low boots favored by construction workers called over her co-proprietress, physically and sartorially her clone--they might have been sisters or lovers--for a consultation. I got asked how my accident could have occurred; my answer was duly greeted with incredulity, but eventually with a reasonable promise that something might be done with light sanding and unguents to rehabilitate the furniture.

At this point, my Frenchless husband chimed in, in English, with some details about the incident and queries about the repair (since he would be carrying it out), which he evidently thought might be helpful to all concerned. I broke in to explain the obvious to him and the co-proprietresses: the fact that they had no language in common, but if they'd allow me to be the go-between, I'd be glad to translate. Whereupon the first woman reprimanded me sternly with the French equivalent of "Be quiet, Madame, Monsieur is speaking."

Long after graduating from college, with its academic approach, I learned Danish, and then I decided really to learn French, not simply the formal language of France's heavenly literature that dominated our college curriculum: La Chanson de Roland, which made me (a confirmed pacifist) understand why men, especially, found glory in war; Joseph Bédier's reconstitution of the medieval legend of Tristan and Iseut; the sonnets and odes of Ronsard; the essays of Montaigne; the tragedies of Racine; the comedies of Molière; the letters of Mme. de Sévigné; the fables of La Fontaine; the plays of Marivaux; the children's tales of the Comtesse de Ségur. . . .

Understand that this is just a random sampling that ignores the moderns and is skewed by personal taste. College French had introduced me to these and other texts in which I've reveled ever since. A lab course, to which I had applied myself obsessively, had polished my accent. But what I coveted now was conversation--the simple ability to take my place in those exchanges, some casual and trivial, some deeply intimate, in which people revealed themselves to one another through words. As I had done with Danish, I thought up a handful of ways--homemade and occasionally eccentric--in which this might happen. I'm still working on this method, vastly preferring the organic quality of self-taught means to formal instruction.

I read French children's books of increasing difficulty, pronouncing the words inside my head. In Manhattan, my home town, if I spot tourists looking puzzled over a map and murmuring worriedly to one another in French, I'll ask, in French, if I can help them--and do. I haggle in French in the flea markets on trips to Paris. Once a price has finally been agreed upon, sellers, to relax the conversation, often ask me where I'm from. "Guess," I say with a smile, They never guess America. My biggest compliment so far has been, "Not Paris, but another part of France."

Renée hasn't the stamina for house guests anymore, other than her immediate family, but for years, once our friendship had developed into nearly annual stays of a week or two with her and her husband, she and I talked about nothing and everything. When I was in residence, we'd often meet unexpectedly in the long book-lined corridor that ran through her apartment when I returned from hours in the museums. She'd say, "You must be tired. Come and sit down," and lead me into her bed-sitting room overlooking a terrace filled with plants and birds, which she tended assiduously.

There we'd talk for an hour or more, à batons rompus (at random), as Renée put it, over espresso, an addiction we had in common. Through those conversations--in French until I'd exhausted my linguistic tenacity, in English (which she spoke fluently) when the subject matter outdistanced my vocabulary--we forged a bond that, as far as I'm concerned, will exist until I die.

When I was young, I planned to learn six languages before I died. I had even them picked out: French, ancient Greek, Yiddish (because of my ancestry), Japanese, Italian, and American Sign. Now, many decades and two foreign languages later, I realize how hard it is to acquire another tongue if you can't live in a heartland where it's spoken almost exclusively and its sounds fill the air. But I have at least learned that absorbing a language that is not your mother tongue opens worlds of imagination and adventure. It swells the soul.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

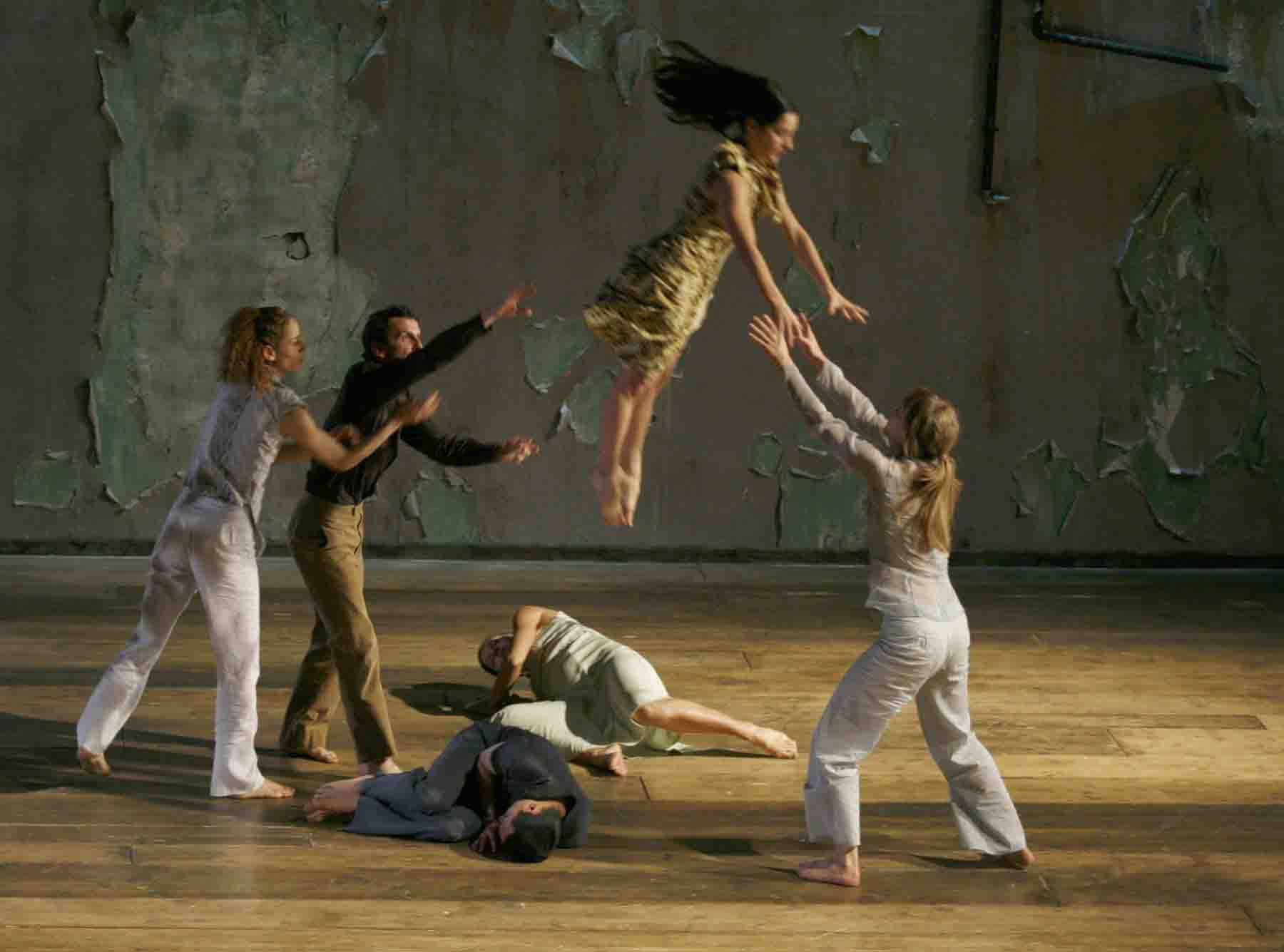

Sasha Waltz & Guests: Gezeiten / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House / November 3-6, 2010

Three doors, phantasmagorically mismatched, open onto an empty room. The paint on its walls has peeled away in jagged fragments to reveal two previous colors. This derelict space could provide shelter only to the desperate. One of the doors has a thick brick frame that juts into the room. It's easily imagined as the entrance to a crematorium; instantly you think Holocaust. It turns out that Sasha Waltz, who choreographed this dance-theater piece--Gezeiten (Tides), at BAM's Howard Gilman Opera House, November 3-6--has been thinking about a more inclusive range of crises and catastrophes: 9/11, Katrina, earthquakes, tsunamis, genocide--all the disasters, natural and man-made, that the human flesh and spirit are heirs to.

Line-up: Sasha Waltz & Guests in Gezeiten

Photo: Richard Termine

Gezeiten is divided into three sections. The first is the most recognizable as dancing. Its mood is set by a man and woman who enter first, one body tightly behind the other, like sardines in a can. The pair paces the room cautiously, staring straight ahead, as the blind might. Other couples join them, replicating the first couple's posture and gait, but soon the whole group flares out into bold motion, limbs partitioning the air, one partner propelling or cantilevering the other, exiting and reentering, then beginning to run--away from what? toward what? They toss each other's bodies into the air with increasing vehemence. In between these wildly accelerating moves they return to order in a series of long line-ups. Rooted to the floor, they rise and sink in simple patterns. Pattern itself segues into the mechanical, then obsessive repetition of a single gesture. All the dancers flee but one, who remains in a slowly failing light, mindlessly reiterating the group's last move.

Some of this material is accompanied by silence, some by fragments of Bach's music for the cello, played by a man in a downstage corner, as if to remind us that bodies still able to respond to rhythm and melody by dancing retain some aspect of their humanity. Then the ambient sounds of war and destruction take over.

The second section is more literal, like silent film or naturalistic pantomime. The doors are now shut. Furniture has appeared--tables, chairs with screaming-red plastic upholstery as if from a cheap mid-20th century luncheonette, and a worn-out bed with an iron bedstead. The dancers--settlers in this closed camp--battle amongst themselves, then stack the furniture and climb onto its precarious safety. One guy becomes self-elected bully-in-chief, urging the mob to join in the abuse of his scapegoat, even after the helpless man has fallen. The agitated crowd gabbles in a cacophony of languages (the cast actually comes from many different lands). Another man starts tearing up the floorboards, eventually erecting four tombstone-like crosses on the site. A small woman hunched over a black pail--containing what?--sobs unremittingly. A woman in a white clinician's coat tries to comfort her (in vain of course).

Lean: Sasha Waltz & Guests in Gezeiten

Photo: Richard Termine

The group quiets down, eats, drinks, forms a docile chorus to sing a little folk song sotto voce, then turns against its own members once again. Suddenly they're besieged from outside--air-raid style sounds, smoke, darkness, fire--by a force against which their shelter proves inadequate. The fire shoots up in a single spiral, orange and yellow flames greedily rushing upward, apparently stealing all the available air. The fugitives collapse and vanish--except for the woman who grieved over the contents of the black bucket (the remains of her child, I guessed morbidly). As if finally accepting the inevitable, she puts herself to sleep on the worn-out mattress of the iron bed.

The third and last section of Gezeiten is a succession of surreal events that the spectator must interpret as s/he chooses. With the doors open again, "stuff" keeps on happening, in vignette after vignette. It's well-nigh impossible to know what any of the events signify or how they relate to one another. The most solid item in this theater of the absurd has the floor boards mysteriously rising up at crazed angles and crashing down again, accompanied by hacking sounds, then darkness again, with quick-shifting beams of light ferreting out figures hunting god knows what, fleeing, or--justifiably, to be sure--going berserk.

It's in this final section that you see why some dance observers believe Waltz has been influenced by the late Pina Bausch. The stage is full of Bauschian enigmas, Bauschian violence, even a sumptuous Bauschian evening dress or two (though not, as in Bausch's earlier works, from the thrift shops, but more along designer lines, as in the later ones.) There are, moreover, Bauschian rivulets of water, spilling portentously and ludicrously from unlikely orifices. Lacking, alas, is the sense one had with Bausch (before she tamed her aesthetic) of a choreographer throwing caution to the winds as well as the wry Bauschian sense of humor.

Most significant, however, is the fact that all the strange visions Waltz conjures up lack theatrical power. One reason for this is that too many things are occurring at once, but the material itself just isn't charged. I won't bother you with details on the finale, dominated by some giant worms who had apparently inherited the earth; it was simply too silly.

Trust: Sasha Waltz & Guests in Gezeiten

Photo: Gert Weigelt

I was interested in Gezeiten almost all of the time I was watching it--though nearly two hours of attention to work like this without any intermission is asking a lot of many viewers. Yet the more I thought about the piece afterward, the more I found it wanting. Most peculiar, I think, is the fact that the piece is not expressive. Events just happen, but the dancers--otherwise very deft and precise--project very little, if any, emotion about their plight. Sorrow, joy, rage, fear, and panic seem to have been excised from their vocabulary. Obviously they were carrying out the instructions they'd been given (perhaps along the lines of Balanchine's "Don't act dear; just do.") But the Waltz who states in interviews that she's charting the broad spectrum of people's reactions to dire situations and who claims, moreover, that she's illustrating the idea that reconstruction always follows destruction--that Sasha Waltz reads more eloquently than what is actually accomplished on her stage. Of course in Europe--Waltz is German and based in Berlin--program notes are considered an integral part of the show.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary