Seeing Things: October 2010 Archives

Kidd Pivot Frankfurt RM: Crystal Pite's Dark Matters / Alexander Kasser Theater, Montclair State University, Montclair, New Jersey / October 21-24, 2010

Name Crystal Pite and most of the dance enthusiasts I know still say "Who?" Maybe it's just America that doesn't know her. Yet. Pite's had a solid career as a dancer--in her native Canada and beyond, notably with William Forsythe, in Germany. Turned choreographer, she's created pieces for companies of some rank, among them Nederlands Dans Theater, Ballett Frankfurt, and Les Ballets Jazz de Montréal. She now has her own troupe--Kidd Pivot Frankfurt RM.

I first saw Pite's work in New York when Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet performed her Ten Duets on a Theme of Rescue. Amidst a familiar crop of would-be chic, portentous, hollow works (beautifully danced, mind you), it made its mark. Abstract with an emotional subtext, it was meaningful as I watched, and proved to linger in my memory. So off I went to New Jersey to see Pite's program-length Dark Matters, part of the Peak Performances series at the Alexander Kasser Theater, on the campus of Montclair State University. NIMBY, you might say.

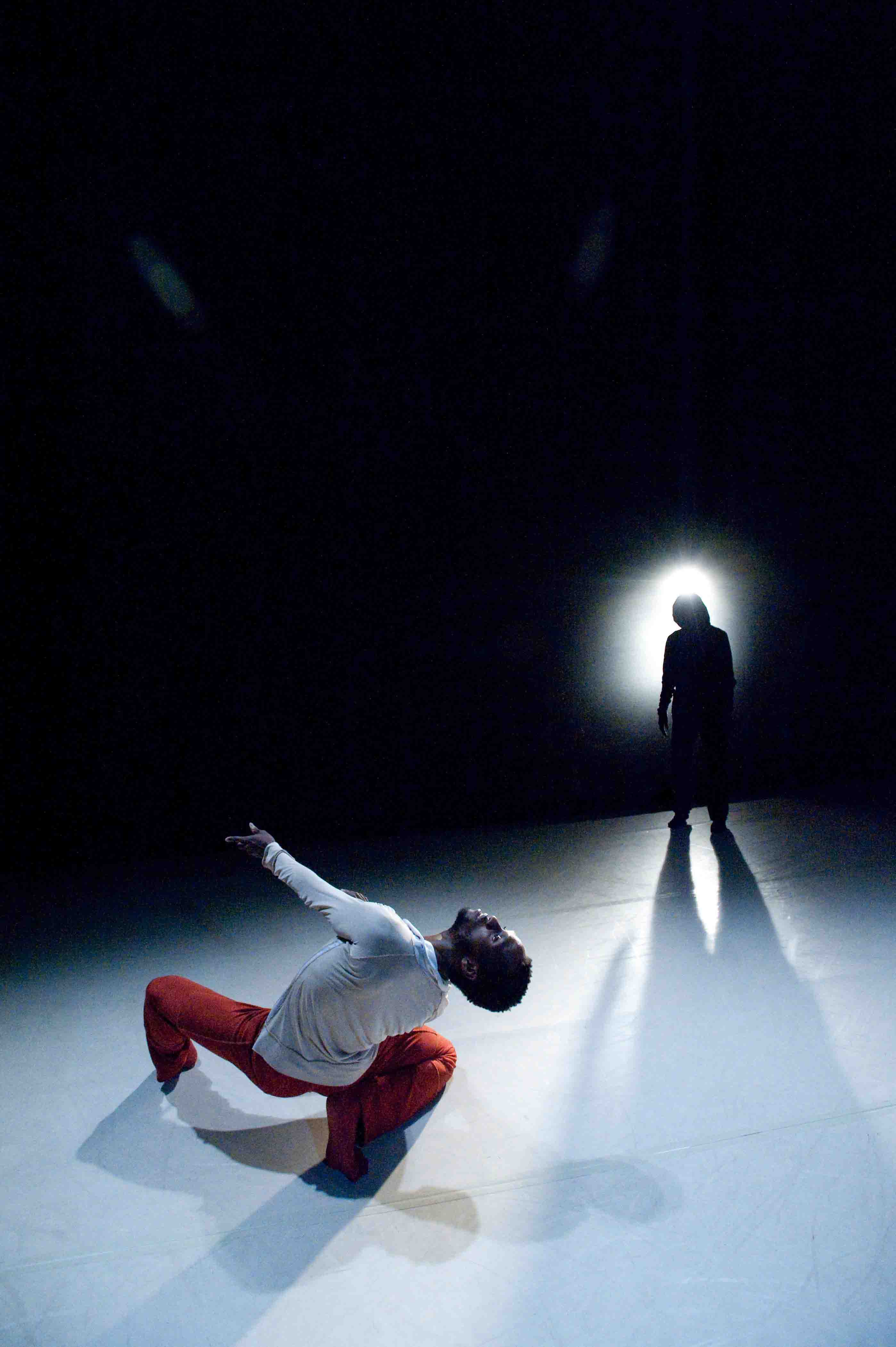

"We work in the dark . . . ": Crystal Pite's Dark Matters, for Kidd Pivot Frankfurt RM

Photo: Dean Buscher

Quotation: Henry James

Dark Matters (the latter word can be taken as noun, verb, or both) has two parts, separated by an intermission. The first half is bound to charm everyone. Performed by itself, it would be perfect for the New Victory Theater, which deals in productions for children that won't drive the sophisticated adults escorting them to thoughts of infanticide due to the boredom or revulsion that crude or stupid "kiddie" shows arouse in them.

Our first glimpse at the rise of the curtain is, indeed, darkness. Then scanning beams of light--as if from a detective's flashlight or searchlights from the roof of a prison, thwarting escapes--pick out segments of a poky pre-modern study where an Inventor (let's call him) works, obsessively intent on his latest project. The scene is simply rendered by Jay Gower Taylor, yet it's redolent of Dickens, or maybe Edgar Allen Poe, or then again E.T.A. Hoffmann, whose tale The Sandman inspired the libretto for the ballet Coppélia.

With a steadier if still dusky light we see that the Inventor is fashioning a mannequin with articulated joints--a cousin to the ones artists use for anatomical drawings. A quartet of puppeteers appears--or were they always there, in the shadows?--to manipulate the finished figure with miraculous exactitude. As in traditional Japanese theater, these facilitators are completely shrouded in black; even their faces are veiled. They huddle together, wielding long wands with strings that attach to the delicately built miniature man. Self-obliterating, they nearly convince the viewer that the Inventor is teaching the mannequin to walk, each stage of that difficult, glorious process exquisitely defined.

But many an inventor has seen his creation get out of hand and turn on him in close-to-human guise, lacking nothing but a soul. Literature loves the theme: Think of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Think of Frankenstein. Think of Hoffmann's Automata as well as The Sandman. As soon as it can walk fluidly, the Inventor's mannequin begins to display feelings--first hurt, then annoyance, then rage against its creator. Its attacks grow increasingly violent until they wreck the room and then the man himself. Both are left lying inert--motionless, unconscious--in exactly the same position on the workroom floor.

To this old theme, usually filed under the rubric of (entertaining) horror, Pite adds the dimension of humor. She makes the whole process of science usurping God's role as creator-in-chief funny--funny in the best way, which involves magic, irony, and a definite vein of the tragic.

Ties That Bind: Kidd Pivot Dancers in Pite's Dark Matters

Photo: Dean Buscher

The second half of Dark Matters is ostensibly an abstract version of the first half. And indeed certain moves in Part One are repeated in Part Two, like dutiful reminders of the preceding narrative. Overall, though, the movement is hit-the-mark precise and extraordinarily powerful, the energy emanating surprisingly from shifting zones of the body. You wouldn't want to get in its way.

Solos seem to make statements, though you'd be hard put to name their various topics. Group passages, which owe a lot to contact improvisation, emphasize twining and cantilevering. But, sad to say, despite the dancers' whiplash power, most of this half is not as engaging as what came before. It goes on too long, too, making us all the more aware of our disappointment. This section is redeemed in a way--and the whole piece unified--by a final, contrastingly tender, passage in which the slight, graceful man who played the Inventor gently solaces and supports a woman almost stripped to the skin, helps her flex her knees and ankles and--yes--walk. Together they manage a slow, quiet duet of mutual aid and mutual commitment, which is, perhaps, as close as post-modernism can get to love.

"Our doubt is our passion . . .": Jermaine Maurice Spivey in Pite's Dark Matters

Photo: Dean Buscher

Quotation: Henry James

In interviews and in a personal statement from Pite tucked into the press kit, the ultra-brainy choreographer talks about scientists' concept of "dark matter." It's a force, they claim, that makes up a goodly portion of the universe. However, they can only infer its existence and nature; as yet they have no absolute proof. According to Pite, the doubt that haunts this theory parallels a dance-maker's (i.e., her own) "not knowing" about her creations, which causes her to work in a state of agony, and so forth. She even quotes the playwright John Patrick Shanley in her program notes: "Doubt requires more courage than conviction does, and more energy; because conviction is a resting place and doubt is . . . a passionate exercise." We don't need to know all this; Pite's piece speaks for itself--and positively about her future.

The audience for Pite's opening night by no means filled the house, but it was certainly enthusiastic. More than half of the viewers were young people whom I took to be Montclair State students. This largely local crowd made me wonder how much of the NYC audience Montclair could attract on a regular basis. The Brooklyn Academy of Music finally persuaded Manhattanites that they could cross the river for art's sake, but BAM was accessible by public transportation within the MetroCard zone. For NYC dwellers, who are often car-less, Montclair is still a stretch--as much mental as geographical.

The Kasser Theater is accessible by charter bus from the Port Authority Bus Terminal on weekends and by a NJ Transit line from Penn Station on weekdays. The travel cost is rock bottom as are tickets to the shows. Still, why bother, when Manhattan (with some help from BAM) is still the dance capital of (at least) America? I'll tell you why: For several seasons now, Jedediah Wheeler, executive director of the Kasser's arts and cultural programming, has exercised his sense of what's unique and worthy to choose forward-looking choreography that honestly deserves that description.

Granted, if you're a New York dweller, the Kasser is not a mere twenty minutes away from your hearth. But surely you can count the travel time as a little vacation from the hubbub of urban life and chat with your seat mate, do those deep-breathing exercises meant to relieve your stress, read, or simply dream. When you arrive, inhale slowly; the air is amazingly fresh.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake / New York City Center / October 13 - November 7, 2010

Once upon a time, as Matthew Bourne tells us, there was a crown prince, a supersensitive fellow with an emotionally frozen mother (see Freud). Naturally, he gets himself entrapped by a tiara-coveting floozy (see the tabloids' take on royalty), all the while fumbling at and fretting over the arid court duties he despises.

His instincts for romance, sex, true love, freedom from constraint, even rendezvous with danger--every young man's birthright, wouldn't you agree?--lead him down an unusual path. Moonlit, it takes him to the water's edge, where he encounters the flock of swans he has often dreamed of. (At home in bed, his sleepy-toy is a plush swan.) The leader of the flock, called simply The Swan, and indeed all of the others are male--with shorn heads and bare chests chalked white, faces scored by an inky streak suggesting a beak, nether parts concealed to the knees with thickets of white feathers. Moving with heavily muscled grace--now blunt, now sensuous--they convey a terrifying power.

Swann's Way: Jonathan Ollivier (front & center) and his flock in Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake

Photo: Bill Cooper

I can't wait any longer to say that the current version of Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake, at City Center through November 7, is the most gratifying re-invention of the Petipa-Ivanov Swan Lake, I've ever had the good luck to see. The production, a significant reworking of the piece since its first New York run in 1998 (it premiered in London in 1995), gives it far more meaningful dance--in terms of steps, gesture, and deeply visceral execution--and this is exactly what it needed.

Set to a recording of Tchaikovsky's evocative score (essentially uncut) for the original ballet, Bourne's Lake operates in three different arenas--often simultaneously. The simplest is an account of royal life, which turns palace into prison, encourages covert misbehavior (Her Majesty's daily agenda is a mix of opening exhibitions, christening sea liners, and secret trysts), and suppresses basic human instincts so that they must be converted into over-the-top dreams. The second is an account of the life of the id, which can be thwarted but, blessedly, never fully quelled. Last but far from least is the spinning of a complex and subtle relationship of the Bourne version to the traditional Swan Lake. The latter is, of course, the emblem of classical dance, with its tragic tale of the poignant Odette, transformed into a swan by a wicked, perhaps lascivious, magician; her evil alter ego, Odile (a single ballerina usually portrays the stories of both O's); and Prince Siegfried, who is fatally distracted by the glittering bad girl into mistaking her for the good one.

This multilayered arrangement is ambitious and, to be frank, it doesn't always cohere. Nevertheless, as with Alexei Ratmansky's wonderful Namouna, you forgive the little lurches because the material is so fertile and engaging and its treatment so full of wit and blows to the heart.

The top stars of Bourne's Lake on the night I saw it (the taxing main roles are double-cast) were Simon Williams as The Prince and Jonathan Ollivier in the dual role of The Swan (Odette) and The Stranger (Odile). Williams, persuasive because of his boyish looks and earnest attitude--like those of the young Baryshnikov--is a very good dancer and a resourceful actor (when he despairs, as he often does, it's hard to resist giving him instant empathy.)

Ollivier as the Odette figure in Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake

Photo: Bill Cooper

Ollivier is a remarkable dancer--long and lean, with a space-slicing leap that conjures up an image of a sword doing its worst. In his Odette guise, he's a mournful outsider seeking a love he yearns for but has never known. In his Odile incarnation (wearing provocative black leather trousers) he is raw, ruthless, and commanding. Crashing a dressed-to-kill party at the castle, he makes aggressive sexual overtures to every femme in sight, doing double duty with The Queen (Nina Goldman, cool even at her most randy) and turns the presentation of the princesses auditioning for the role of Consort to the Heir Apparent into a satisfyingly wild orgy.

The high point of the dancing is the love pas de deux for The Prince and The Swan. The duet has a vein of antagonism--often a part of lovemaking--but inevitably the two succumb to the white heat of their mutual attraction. The movement vocabulary is, first and foremost, very creaturely, full of well-observed swan mannerisms and extensions of them. The Swan nuzzles The Prince with the sweetness of an adolescent newly aware of physical love. The Prince lifts The Swan so that the bird appears to take flight in all its wide-winged magnificence and the image becomes a metaphor for the notion that both partners are soaring high--on the joy of finding, against all odds, the perfect mate.

The ensemble extends the idea of the wild, free animal driven by primal instincts with movement that's bold and weighty, sinewy and sensuous, insinuating a danger that's implicitly evil.

The Prince achieves ecstatic release in his mating with The Swan at the price of his life (and The Swan's life too). True to their breed, the swans in this covey are vicious when the objects of their attachment are threatened. (Once, in Central Park, I fled from a male swan that decided I was getting too close to his cygnets.) The swans turn on their leader and his lover and destroy them. But Bourne allows his Swan and Prince the apotheosis tradition calls for. Through a skylight in the Prince's bedroom the pair can be glimpsed together--at last and forever. I didn't weep when I saw this last night, but now, remembering it and writing about it, I feel, welling up, the tears it has earned.

Admittedly I'm a Janey-come-lately to admirers of this show. I managed to resist it--vigorously--at its New York premiere a dozen years back, though it subsequently copped three Tony Awards. The production has been touring worldwide ever since, applauded by a great range of spectators, from balletomanes to folks cheerfully unaware of--or perhaps immune to--the pleasures of classical dancing. Meanwhile Bourne has created other works for his company, New Adventures, several of them with similarly oblique takes on landmark works of art. I hope that next time round, I'm quicker to catch on.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

By Martha Ullman West, guest contributor

A recent National Endowment for the Arts survey shows that per capita attendance at the ballet in Oregon is fourth in the nation; in Washington State it is even higher. Could this be because we have decent-to-excellent ballet in a part of the country better known for the bounty of its rivers, the height of its trees, and the beauty of its scenery?

Lord knows, ballet attendance in the United States as a whole is woefully small (at best four percent of the population, surveys show), and the three major companies in this region--Seattle's Pacific Northwest Ballet, Portland's Oregon Ballet Theatre, and the Eugene Ballet Company--are in a constant struggle for financial survival. Nevertheless, they are managing to produce pretty much the same array of story ballets as the big guns in New York and San Francisco, including, not surprisingly, The Nutcracker, in three different versions. OBT is the only west coast company performing Balanchine's; PNB does Kent Stowell's, with Maurice Sendak's sets and costumes; EBC performs artistic director Toni Pimble's pirate-themed rendition.

This season, the Seattle and Eugene companies will present Cinderella; PNB will perform Balanchine's A Midsummer Night's Dream; and OBT opened on October 9 with its first evening length Sleeping Beauty, staged, after Petipa, by artistic director Christopher Stowell. With a company of 32 dancers and apprentices, the challenge is the ensemble dances, not the principal roles or divertissements, although many roles will be double and triple cast. Three company ballerinas are capable of a fine, nuanced Aurora: Alison Roper, Yuka Iino, and Kathi Martuza, and I look forward to seeing them partnered by principals Artur Sultanov, Chauncey Parsons, and such upcoming soloists as Brennan Boyer.

Alison Roper and Kevin Poe in Oregon Ballet Theatre's production of artistic director Christopher Stowell's A Midsummer Night's Dream

Photo: Blaine Truitt Covert

When Stowell took over OBT's directorship in the fall of 2003, following the departure of founding artistic director James Canfield, the last thing I expected was a traditional, program-length Beauty seven years later, or for that matter, in June 2006, a complete Swan Lake. Canfield, well trained in the classical tradition by Mary Day, had mounted Beauty's Act III early in his tenure, which began in 1989, and his own Nutcracker, in a gorgeous Campbell Baird production, emphasized 19th-century classicism. The repertory did contain several Balanchine ballets, a decent version of Giselle thanks to then ballet master Mark Goldweber, and, while he was still alive, the neo-classical ballets of associate artistic director Dennis Spaight. Canfield commissioned work from Donald Byrd, Bebe Miller, and Karole Armitage, and, to his credit, from Portland's modern-dance choreographers.

However, in part for financial reasons, the emphasis at the end of Canfield's tenure was on his own work, which had increasingly moved away from traditional and neo-classical ballet. Let it be said that Canfield, who had a short but stellar performing career with the Joffrey Ballet and continued to dance for nearly a decade with OBT, is an extremely good teacher, and insisted on strong classical technique at all times; he just stopped using it in his choreography.

Stowell, the son of Francia Russell and Kent Stowell, PNB's founding artistic directors, trained by his parents and the School of American Ballet, enjoyed a lengthy dancing career (16 years) with the San Francisco Ballet, performing in a wide array of choreographic styles, from Balanchine's to Mark Morris's. The minute he hit town in July of 2003, he drew on his contacts with choreographers in whose work he had performed, not to mention the Balanchine Trust. His first season, which happened to be Balanchine's centennial, included his Rubies; The Nutcracker, alas in a dreary second-hand production; Serenade, already in the rep; and Duo Concertant. The opening program told Portland precisely where he came from, adding to the curtain-raising Rubies a Helgi Tomasson pas de deux, his father's Duo Fantasy, and Paul Taylor's Company B.

The rest of the season was a clear indication of where Stowell was headed. February concerts included the premiere of a new Firebird by Yuri Possokhov in a charming production with children from OBT's school cast as monsters, and the premiere of Stowell's own Adin, a modest work to Shostakovich. In the concluding concerts, Christopher Wheeldon's There Where She Loved received its American premiere, programmed with Julia Adam's new Il Nodo, danced to medieval music, and, to my joy, Ashton's Façade, staged by Alexander Grant. It was, after all, Ashton's centennial as well as Balanchine's.

In subsequent years, Stowell added works by Jerome Robbins, James Kudelka, Trey McIntyre, Twyla Tharp (the "Junk" duet from Known by Heart, not, thankfully, yet another Sinatra Suite), and Wheeldon's Rush. He also commissioned two ballets from Nicolo Fonte. Bolero, which premiered on a French program in 2008 and was seen again at the conclusion of last season, could well become a signature piece for the company. While it is marked by the style du jour--relentless high-energy dancing--Fonte, unlike Jorma Elo and Stanton Welch, among others, understands that just as comedy underscores tragedy, stillness and breath highlight speed. For me, last season's best program was February's pairing of The Four Temperaments with Stowell's one-act A Midsummer Night's Dream, a delicious, sophisticated take on Mendelssohn's music. Stowell's choreography in general is marked, as was his dancing, by intense musicality, intelligence, and wit.

A hundred miles south of Portland, the Eugene Ballet is directed by Toni Pimble, one of the very few women now heading a ballet company. She and Riley Grannan, who is the managing director, founded the company in 1978, using their state retirement money from their years of dancing in German opera ballet companies. Grannan grew up outside Eugene; Pimble is British and received her training at the Elmhurst School. Like most artistic directors, she brings her experience as a dancer to the job, and her sensibility remains quite British, particularly as expressed in her Cinderella and Romeo and Juliet. Over the years, however, she has learned about her new country by making some very interesting ballets based on Native American culture--Children of the Raven and The Skinwalkers, the latter inspired by the paintings of the Native American artist Helen Hardin. For Skinwalkers, she invented a movement vocabulary that completely avoids stereotype and is appropriate to Pueblo dancing without trying to replicate it.

Jennifer Martin and Hyuk-Ku Kwon in Still Falls the Rain, choreographed for Eugene Ballet Company by its artistic director Toni Pimble

Photo: Ari Denison

Pimble is a versatile choreographer, who created a well-received neo-classical ballet, Two's Company, for the New York City Ballet's first Diamond Project in 1992. She has also made work on the Atlanta Ballet, Nevada Dance Theatre, and, most recently, Kansas City Ballet. A feminist--and why wouldn't she be?--Pimble has made two ballets that are highly political: Columba Aspexit, only five minutes long, which premiered on a program of work by women choreographers to music by women composers in 1992, and in 1997 the stunning Still Falls the Rain, an abstract indictment of fundamentalist religion, based on a Taliban incident in Afghanistan, created long before 9/11 took us to war there.

While there are only four concert seasons a year in Eugene, the company tours extensively throughout the region, and with more than The Nutcracker, taking its 21 dancers, who are an international bunch--Grannan spends a lot of time filling out immigration forms--to communities as small as Florence, on the south Oregon coast. The upcoming season starts with Cinderella on October 16 and the traditional family-oriented February show contains Pimble's Alice in Wonderland, which has a smashing corps de ballet of flamingos, coupled with a new piece by Jessica Lang. The season ends with Maurico Wainrot's Anne Frank and a new piece by company member Gilmer Duran.

PNB did not open its 2010-2011 season with a story ballet, though Peter Boal, who took over from founding artistic directors Francia Russell and Kent Stowell in 2005, following his retirement as a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet, is ending it with the company's first Giselle. Boal, like Janet Reed (who founded PNB's School in 1974), Russell, and both Stowells could be categorized as part of the Kirstein-Balanchine diaspora, and he has, to be sure, both maintained and added to the company's extensive Balanchine repertory, but in his five-year tenure he seems to be shifting the paradigm.

This season, the only Balanchine programmed is A Midsummer Night's Dream, and, judging from the opening program as well as an all-Tharp evening scheduled for early November and a Contemporary evening in the spring that includes a world premiere by Marco Goecke, one can justifiably speculate that this neo-classically trained dancer is de-emphasizing what one might call the mother tongue. Under the umbrella title of Director's Choice, he opens with two ballets by Jírí Kylían, Petite Mort and Sechs Tanze (a company premiere); Jerome Robbins's Glass Pieces, another PNB premiere; and a longtime PNB standard, Nacho Duato's Jardi Tancat. Only Glass Pieces reflects his own past with NYCB, which, to his credit, he has used to add quite a bit of Robbins's work to PNB's rep. The Duato, which he seems to trot out whenever the company goes on tour, a pleasant enough piece that shows the dancers can perform ersatz Graham, he owes to Stowell and Russell, who also added a great deal of contemporary work to the rep, particularly in the company's 25th anniversary season.

Carla Korbes and Lucien Postlewaite in Pacific Northwest Ballet's production of Jean-Christophe Maillot's Romeo and Juliette

Photo: Angela Sterling

Boal is determinedly not himself a choreographer; what he wants to do is bring work to the Seattle audience that it hasn't seen before, and to challenge PNB's fine-tuned, classically trained dancers to perform in new ways. Perhaps his most successful attempt at that was when he presented Jean Christophe Maillot's Romeo and Juliet a couple of years ago, giving Louise Nadeau an extraordinary role as a seductive Lady Capulet and Olivier Wevers a highly sinister one as Friar Laurence. Commissioning Twyla Tharp to make two new pieces on the company was something of a coup as well. PNB remains a major company under his direction, and he and his regional colleagues are providing audiences with plenty to see. That may have something to do with comparatively high attendance at the ballet. And it certainly makes me happy.

© 2010 Martha Ullman West

Martha Ullman West grew up in New York and is now based in Portland. She has been writing about dance for Dance Magazine, Ballet Review, The Chronicle of Higher Education Review and many other publications since 1980. At present she is under contract with University Press of Florida for a book titled Making Ballet American: Todd Bolender and Janet Reed.

Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen / Museum of Modern Art, NYC / September 15, 2010 - March 14, 2011

Fall for Dance / City Center, NYC / September 28 - October 9, 2010

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Brooklyn, NY / September 29 - October 9, 2010

Trisha Brown Dance Company / Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC / September 30 - October 3, 2010

Every now and then I steal time from dance, my regular beat, to indulge another passion: old things--vintage fashion, vintage films, vintage photography, and, yes, even vintage housewares. So of course I scurried over to the Museum of Modern Art to ogle Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen. It's at once a charming and sociopolitically resonant exhibition--the latter because, if you wanted to study the role assigned to Woman, where, until the last half-century, would you have been likeliest to find her?

Woman's Workplace: Margrette Shütte-Lihotzky's "Frankfurt Kitchen" in the Museum of Modern Art's Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen

The centerpiece of the show is a real room--the "Frankfurt Kitchen," designed for public housing in 1926-27 by Margrette Schütte-Lihotzky. Not an inch of space is wasted here; austere form follows practical function without once succumbing to the adornment or idiosyncrasy that would indicate human life. Nearly all the storage space is painstakingly compartmentalized, its contents hidden but ready to hand. Peering into this room, you imagine you could stand at its center with at least one foot fused to the floor and prepare a multi-course dinner (for agoraphobics it would be paradise).

Seconding this a-place-for-everything-and-everything-in-its-place example is a late 1960s mini-kitchen cannily devised as a series of hinged rectangles. Unfurled, it reveals dedicated storage spaces; closed, it becomes a pair of hygienic-white boxes. Both kitchens pay homage to the gods of ever-increasing efficiency and, ostensibly, progress.

Second in importance only to the kitchens themselves are the handsome tools of the culinary trade, lined up in capacious vitrines. Lots of these objects will be recognizable to the comfortably-off as part of their own batterie de cuisine or that of their mother or grandmother. Most of them, sleek as Brancusi sculpture, are clearly striving to be works of art--sometimes, as I know from personal experience, at the expense of functionality.

Much as I admired the damned good design of all these things, I was gradually depressed by the pervasive sterility. When the person with whom I share a kitchen cooks, the room ends up looking like Berlin after World War II. Where, I wondered (granted, inappropriately), is the mess often associated with action--and thus with life itself? Should we cling to the Bauhaus tenet of "less is more" when chaotic abundance offers so much vitality? Ironically, chaotic abundance abounded, one way or another, in the dance events I saw in the two weeks that followed my MOMA fling.

Fall for Dance, in its seventh season at New York City Center, intentionally offers everything but the kitchen sink. It's designed to attract newcomers to Terpsichore's Wonderland, enticing them with $10 tickets to any of the 2100 seats in the house and then giving them four items on each program that are as disparate as dance can get, so the spectator is pretty sure of finding at least one item to fire his imagination. This season--completely sold out a week before the series started--comprises five programs, each being performed twice.

Opening night began boldly with Merce Cunningham's complex, abstract Xover (pronounced "crossover"), perhaps the least accessible and most sophisticated work in the whole run. Danced before a backdrop by Robert Rauschenberg and accompanied by two John Cage scores (performed simultaneously), the movement is one of Cunningham's most exquisite exercises in purity.

Maestro: Merce Cunningham flanked by the dancers of his Xover

Photo: Kawakahi Amina

Minimally dressed in white practice clothes, 14 ultra-svelte dancers execute non-narrative, (ostensibly) non-expressive movement that reveals dance pared down to its essence--razor-sharp lines, lyrical curves, delicately shifting balances, and human ardor seeking ecstasy. Its centerpiece is a 7 ½ -minute duet (an eternity in dance time) for a male-female couple in which each partner calmly, delicately, and inventively responds to or supports the other's smallest shift in position or location in space. Like Frederick Ashton's Monotones, it's a vision of Heaven.

Cunningham's company, nearing the midpoint of a two-year world tour following the choreographer's death, after which it will disband--all this according to the late master's instruction--danced, the way all dancers should, as if this performance were their last: fully committed, aware that every living thing dies, and rejoicing in the moment.

This was a tough act to follow. Miami City Ballet, which stunned the New York audience with its vitality on its last visit, couldn't throw caution to the winds as the virtuoso feats and rakish rhythms of Twyla Tharp's The Golden Section demand. This is a company that has already given thrilling accounts of Tharp's In the Upper Room and the daring Rubies section of Balanchine's Jewels. A puzzlement, as Yul Brynner liked to say when he was the King of Siam.

Cross-purposes: Miami City Ballet dancers in Twyla Tharp's Golden Section

Photo: Joe Gato

The seasoned Odissi dancer Mudhavi Mudgal and her four young acolytes breathtakingly turned rouged wrist, palm, and fingers into luscious blooming flowers, but Mudgal's choreography, dependent upon the most banal conventions of Western dance structure, stymied any possibility of transcendence.

The rocket rise to recognition of Gallim Dance utterly escapes me. I Can See Myself in Your Pupil, choreographed (I use the word generously) by the troupe's founder-successor, Andrea Miller, manages to be both unattractive and uninteresting. It mashes together street dance bled of its freshness, gymnastics, acrobatics, and a pervasive yet unexplained hostility between the sexes. (The girls win.) It has no notion of relating to the space it inhabits, the crudest response to music, and an incredible lack of intelligence. No doubt unintentionally, it tells us something about the current state of our culture.

The late Pina Bausch, of Tanztheater Wuppertal fame, was, of course, the diva of mess. In her most potent works--before she betrayed her stern personal aesthetic and opted for pretty--she'd clutter her stage with enormous amounts of litter: earth, water, trodden blossoms, the debris created from a wall of concrete blocks that, just after the curtain went up, fell and shattered before the spectators' eyes. Bausch would have her dancers go about their weird business obliviously treading on such material until it seemed to be a form of post-modern compost.

Subsequently she turned to more dulcet fare--younger, more technically accomplished dancers, as compared to the unique personalities of her earlier companies, and emotional relationships less cruel and fraught than her horrific vaudevilles of what it's like to be human. Never once, though, did she forget to employ her wry humor. Often the laughter it evoked came from confrontation with the absurd, sometimes from the sight of grown-ups bent upon resurrecting their inner child.

Wetlands: Members of the Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch in Bausch's Vollmond

Photo: Laurent Philippe

Bausch created Vollmond (Full Moon) three years before her death in 2009. (This was the troupe's first New York appearance without her at its helm.) Vollmond is recognizably Bauschian in its sensuous indulgence in mess. The dancers wallow in water that seems to rain from above and bubble from below as well, pouring over the stage floor towards the audience. Two hours later, the performers are wildly flinging large buckets of water against the huge boulder that serves as the only scenery, with the rock shooting the water right back--as an arc of shattered diamonds. The piece also conforms to Bausch's customary vignette-by-vignette sequencing, never establishing a firm architectural structure for what's going on. Like the early works, Vollmond is studded with ludicrous behavior and hostile acts, but here these elements are nowhere near so corrosive as they were in the choreographer's heyday. This is Bausch re-imagined by the Walt Disney Studios.

While the strategies of Vollmond seem tired and thin, the work's lack of impact is most evident in the current crew of dancers. Despite their gifts, they are mere shadows of the personas on (and with) whom Bausch originally built her church. The proof? You only have to see the performance of Dominique Mercy, who, with Robert Sturm, is now running the company and trying to discern its proper future. The lone member of the old guard still on stage, Mercy is the real thing, as is evident in his two brief appearances as a ghostly figure who doesn't seem to belong with the others and so, quite logically, and without fuss, disappears, and in an extended contemplative solo as a guy whose quiet, profound melancholy comes from finding himself of two minds. (I imagined this dilemma: Let the company die a natural death? Turn it into a traveling Bausch museum? Join forces with an aesthetically comparable group--what about Sasha Waltz's?--so as to have new work to invigorate the old?) For me, Mercy's presence onstage retrieved the whole evening.

Trisha Brown, a founding star of postmodern dancing and choreography, began her 50-year career by rejecting everything but the kitchen sink when it came to the conventions of theatrical dance--movement married to music, the proscenium stage, costumes, sets, narrative, emotion--and then, without selling out, reclaiming these elements gradually in the course of her development into an internationally appreciated artist. Her recent showcase at the Whitney Museum, in a room cleared for dancers and the spectators who moved freely around them, centered on her Equipment Pieces, notably Walking on the Wall (1971) and Man Walking Down the Side of a Building (1970).

![IMG_5744[1].jpg](http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/IMG_5744%5B1%5D.jpg)

Finessing Gravity: Members of the Trisha Brown Dance Company in Brown's Walking on the Wall

Photo: Graham E. Newhall

In Walking on the Wall eight dancers approach the tall ladders propped against two immaculate white walls that join at a right angle. Men and women both wear long-sleeved t-shirts and trousers that emphasize the fainter gray of their shadows. In turn, each one climbs to a height he or she will "own" and adjusts the harness that envelops the torso and is connected by cables to a track at the top of the wall. One by one, they hunker over their knees, lean out from the ladder, and step into space, placing their bare feet flat on the vertical surface, then standing straight-spined and straight-legged, and then--walking.

They walk forward and backward, stepping with grace and exquisite care over each others' cables when they meet. If, occasionally, one of their number needs an assist, a colleague's hand is extended and accepted, tenderly, then swiftly relinquished. Except for the sound of the cables in the tracks--like that of metal window blinds being opened or closed--the room is utterly silent and entirely calm. Now and then a female dancer who is ebullient in her earth-bound mode substitutes some gently buoyant overcurves for the serene walking pace. For the watcher, gnawing thoughts of danger and risk gradually dissolve as the dancers float across the space, a tribe of worthies for whom the Universal Law of Gravitation has been suspended.

Downhill All the Way: Elizabeth Streb in Brown's Man Walking Down the Side of a Building

Photo: Graham E. Newhall

In Man Walking Down the Side of a Building, the man I saw was Stephen Petronio. (Elizabeth Streb, shown in the photo above, alternated in the role.) The locale was the East 75th Street façade of the Whitney. The technique of the feat was similar to that used in the wall walking, but the effect was far more terrifying. Why? Because it was outdoors, with heavy rains and wind threatening. Because the "arena" was made of stone (with vicious edges). Because, with just one person executing the act--a singular hero, if you will--that figure seemed more destined to suffer a terrible fate. And because, dammit, we knew him.

Apart from pedestrians (and drivers!) who were stopped dead in their (metaphorical) tracks by the sight, the spectators were largely people well acquainted with the dance world. For them, this wasn't just some anonymous stunt man, a professional plying his accustomed trade, who might, sadly, fall to his death, as sometimes happens at the circus. This was Stephen Petronio, an alumnus of Brown's company, now a celebrated choreographer in his own right. He was a real person, for god's sake, as vulnerable as you and me.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary