Seeing Things: June 2010 Archives

Ballet Diary No.8: New York City Ballet: Darci Kistler Farewell; Peter Martins's Mirage; Melissa Barak's Call Me Ben, Maurice Kaplow's Farewell (NYCB's season at the David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC, closed on June 27)

Note: This is No. 8 in the series "Ballet Diary"--comments on the 2010 spring seasons of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, along with related performances. To read previous pieces in the series, click here: No. 1; No. 2; No. 3; No. 4; No. 5; No. 6; No.7. The completed "Ballet Diary" series will comprise nine essays.

Darci Kistler was the last ballerina to capture Balanchine's imagination, and she had a packed, loving house for her farewell performance on June 27 after 30 years with the New York City Ballet.

Swan Song: NYCB's Darci Kistler; directly behind Kistler, in the long turquoise dress, Kistler's and Peter Martin's daughter, Talicia; to the right, in a dark suit, Martins

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Kistler grew up in California with four elder brothers, a situation bound to contribute to her physical prowess and her derring-do. She completed her dance training at the School of American Ballet, entered City Ballet at the age of sixteen and was made a principal dancer only two years later. I saw her first at the annual SAB Workshop Performances--a marvel both as a frisky adolescent in a Bournonville duet (even the air surrounding her seemed fresh), and the next year as an entirely credible Odette in Balanchine's one-act version of Swan Lake. Even then this ebullient teenager, given to rakish street clothes, had an instinct for feeling that allowed her to access the poetic plight and tragic destiny of the Queen of the Swans. Balanchine, who hoped to avert her modeling her interpretation on that of an established ballerina--that is, being anything other than herself--suggested that she visit the zoo to observe the swans; she did.

I recall watching Kistler in Antonina Tumkovsky's advanced women's class at SAB. In the last third of the session, according to custom, these uncannily accomplished adolescents divided into two groups to take turns doing combinations of movement that traveled--hurtled is more like it--across the studio floor. The "resting" dancers were expected to stand quietly in the background, catching their breath and giving their muscles and tendons a break, at most marking the challenging combinations with their hands, But Kistler would dance, full-out, with both groups. Tumey, as generations of SAB students called her, shook her head in admonition, while the expression on her face revealed the pleasure she took in this prodigy.

Pure Movement: Kistler and Sébastien Marcovici in Balanchine's Movements for Piano and Orchestra

Photo: Paul Kolnik

In the prime of her career Kistler was unquenchable: athletic, infinitely musical, radiant--and, where appropriate, so genuinely sweet that she was never cloying. The moment she stepped on stage it was impossible not to watch her. The most technically demanding choreography never fazed her. She seemed to be fueled not simply by the determination that lies behind most stardom but by her sheer delight in dancing.

Early on, however, Kistler was felled by injury and a failed surgical attempt to address it, from which she never completely recovered. This despite the patient, heroic efforts of her most important mentor, SAB's Stanley Williams. One day Kistler, whom I know only slightly, remarked to me about living with incapacity, "I have a little bit of a handicap in there now, but I always think of it like--well, a horse can run beautifully with reins on it, too." (Moved by the pathos of her tone and the courage of her attitude, I wrote her words down.) Much later, surgery for a back problem tamed her even further. Slowly but inexorably, her once-glorious technique diminished. Determined--unstoppable, I'd guess--she continued to perform.

Love Is Eternal: Kistler with Jared Angle in Swan Lake

Photo: Paul Kolnik

As Kistler's career began, so it concluded--with Swan Lake, this time in the final section of the full-length version of the ballet, staged by her husband, Peter Martins. Nearly all she had left at this point was her innate gift for riveting a viewer's attention and the ability of an actress who, in her maturity, can offer a deeper, more complex portrayal of character and situation because she has known something of life. Somehow, on this occasion, that was almost enough.

Earlier in the farewell program, Kistler was the unnervingly shaky center of a pair of abstract Balanchine works, Monumentum pro Gesualdo and Movements for Piano and Orchestra. Then she illuminated the stage with the scene from the master's A Midsummer Night's Dream in which, as Titania, Queen of the Fairies, she falls in love--as a child might, given a marvelous toy--with the uncouth workman, Bottom, magically transformed into an ass.

Those ready to say "She should have stopped earlier" are right, as Kistler's most ardent fans themselves admit, a few of them going so far as to confess that the performances of the late-career Kistler threatened to erode their memory of Kistler in her youth and Kistler in her prime. However they're not factoring in the possibility that, given this ardent ballerina's hunger for performing, she may simply have been unable to stop. Aficionados with long memories will recall that a relentless avidity for the stage has characterized some of the most unforgettable dancers--in both the classical and modern camps: Margot Fonteyn, Rudolph Nureyev, Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham. Artists, like ordinary folks, are only human.

As for the curtain calls at Kistler's farewell performance, they were just as you can imagine. Only more so.

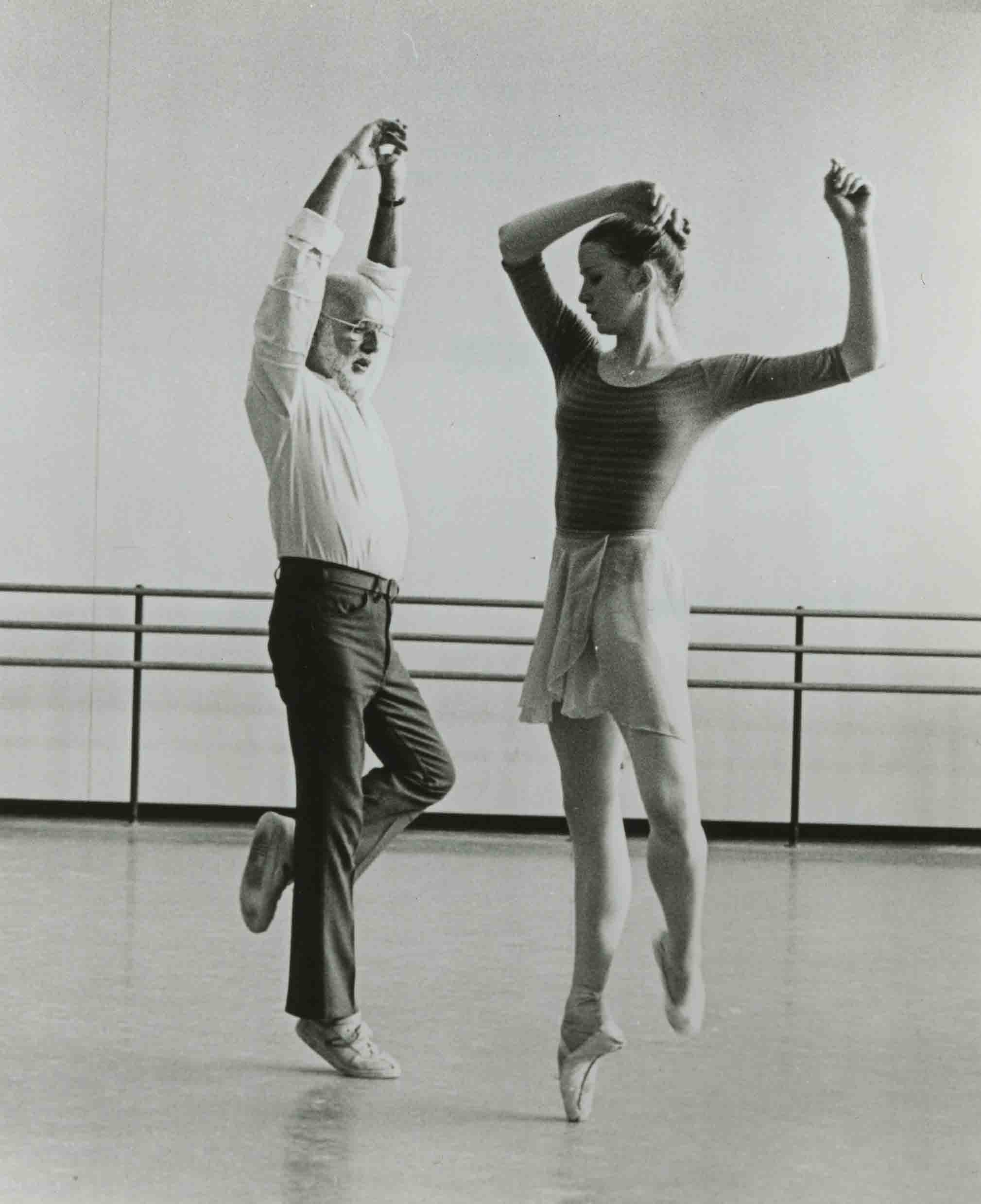

Back Then: Kistler working with choreographer Jerome Robbins

Photo: Carolyn George

Peter Martins's Mirage, the last to appear of the seven ballets created for New York City Ballet's Architecture of Dance festival, was given its premiere on June 22. Despite truly handsome dancing, it looked engineered rather than choreographed, with sterile results.

Architecture of Dance: Calatrava installation hovers over full cast of Martins's Mirage

Photo: Paul Kolnik

An installation by Santiago Calatrava, essentially the architect-in-residence for the season, served as the décor. Hung high above the dancers' heads, it consisted of two half ovals--think of reading spectacles--that overlapped just slightly. The shapes were filled with thin parallel strips that formed moiré patterns with changes in the angle at which the spectator viewed them. The piece moved gently up and down a little ways and folded slightly in and out as if inspired by origami tactics. For its grand finale it was splashed with variously colored light. This last effect, I believe, was what my mother used to call "a lapse of taste."

I finally caught up with Melissa Barak's new ballet, Call Me Ben, commissioned by the City Ballet's Architecture of Dance festival, and it's as dispiriting as colleagues and friends who went earlier have been saying. The audience seemed to think so too, judging by its tepid applause.

Dressed to Kill: Daniel Ulbricht, Jenifer Ringer, and Robert Fairchild in Barak's Call Me Ben

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Barak is a City Ballet alum, now dancing with Los Angles Ballet and choreographing steadily. She has already done a few pieces for her alma mater and its school, which were pleasant but hardly rigorous--not a strong argument for hoping she'd help correct today's dearth of female classical choreographers. Call Me Ben is bigger and punchier than her earlier work, but pretty much a disaster.

It purports to tell the story of Benjamin ("Bugsy") Siegel, the legendary gangster with extravagant dreams, credited with inventing Las Vegas and rubbed out at 42 by a gunman who remains unidentified. To get the colorful tale across, Barak resorts to having the dancers talk (almost always a mistake, because they're not actors and they're out of breath). Only Robert Fairchild, playing the antihero, manages his lines without sounding like a raw teen in the annual school play. The lines themselves, by the choreographer and company dancer Ellen Bar, are puerile.

The dancing Barak choreographs is efficient but innocuous and does nothing to advance--or even tell--the story. At best, it recalls routine stuff made for Broadway musicals half a century ago. Indeed, you expect the cast to burst into song at any moment. I kept wondering if the piece wasn't meant to warm up City Ballet followers for the new Susan Stroman creation announced for the company's winter season.

Barak may have been thinking of Balanchine's Slaughter on Tenth Avenue, to say nothing of Agnes de Mille's ensemble work in musical comedy, but to "borrow" so blatantly from Kurt Jooss (for sinister moves around a long conference table) was surely a miscalculation.

Call Me Ben boasts a score commissioned from the wunderkind Jay Greenberg; it seemed to be doing what it was supposed to do, with more panache than the choreography could muster. Santiago Calatrava provided two mediocre painted backdrops, both dominated by palm trees. The best parts of the "décor" were Jenifer Ringer (delectable in the way sweethearts used to be) as Bugsy's shady No. 1 mistress, Ringer's tailored suit (which any woman in her right mind would kill to own), the men's fabulously cut suits in ogle-worthy fabrics, some of the women's filmy dresses (costumes by Gilles Mendel), and the women's Forties hairdos. All this must have cost a mint.

June 24th saw another NYCB retirement, not in the Sunday series of dancers' farewells, but this time of the company's veteran conductor, Maurice Kaplow. A ballet conductor is usually buried in the orchestra pit, his back to the spectators, except for pro forma bows. On this occasion, given several opportunities to reveal himself to the audience face to face, Kaplow appeared to be the most benign of gentleman--modest, yet radiating joy.

Fond Farewell: Veteran Conductor Maurice Kaplow fêted by the team he served

Photo: Paul Kolnik

He has been with the company for 20 years and helped rescue the musical ensemble from a dismal period in the early 1990s. Kaplow, who is also a violinist, composer, and teacher, is apparently a master of harmony in his home life as well; a press release about the man the public rarely notices makes a point of noting that Kaplow was also celebrating the 50th anniversary of his marriage, which has given him three sons and five grandchildren.

The first ovation Kaplow received from the audience came when the orchestra, in a bit of magical engineering, was raised from the pit to visible level--just like that organist at Radio City Music Hall--to play the overture to Carl Maria von Weber's Euryanthe under his direction. Then, after he'd led his musicians in accompanying Peter Martins's Barber Violin Concerto and Balanchine's Western Symphony, Kaplow appeared onstage for a solo bow beside a free-standing floral arrangement (surely a communal offering) while the audience rose to its feet, clapping like mad.

Next the ballerinas of the evening arrived to fill Kaplow's arms with bouquets, followed by the members of the orchestra, each, in high spirits, tucking a single rose into the bouquets he already held, until the man himself nearly vanished from view.

Then Darci Kistler crossed the stage to present Kaplow with a single rose, curtsying deeply to him. Apart from that tender, solemn moment, the prevailing mood was one of affectionate gaiety. Peter Martins added to it by pulling out a baton and "conducting" the musicians in a rendition of "Happy Birthday," to which the instrumentalists sang simultaneously, joined by the audience. What more was there to do but let scads of multi-hued confetti flutter down to create that tiny theatrical marvel, a tinted snowstorm in summer.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Ballet Diary No. 7: New York City Ballet: Philip Neal Farewell; Albert Evans Farewell (NYCB's season runs through June 27 at the David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC); American Ballet Theatre: The Sleeping Beauty, with Alina Cojocaru and Natalia Osipova as Aurora (ABT's season runs through July 10 at the Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC)

Note: This is No. 7 in the series "Ballet Diary"--comments on the 2010 spring seasons of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, along with related performances. To read previous pieces in the series, click here: No. 1; No. 2; No. 3; No. 4; No. 5; No. 6. The completed "Ballet Diary" series will comprise nine essays.

Until a final solo bow on the flower-strewn stage of the David H. Koch Theatre ended his exquisite farewell performance with New York City Ballet on June 13, if you wanted to see the term danseur noble illustrated in the flesh, you could watch Philip Neal.

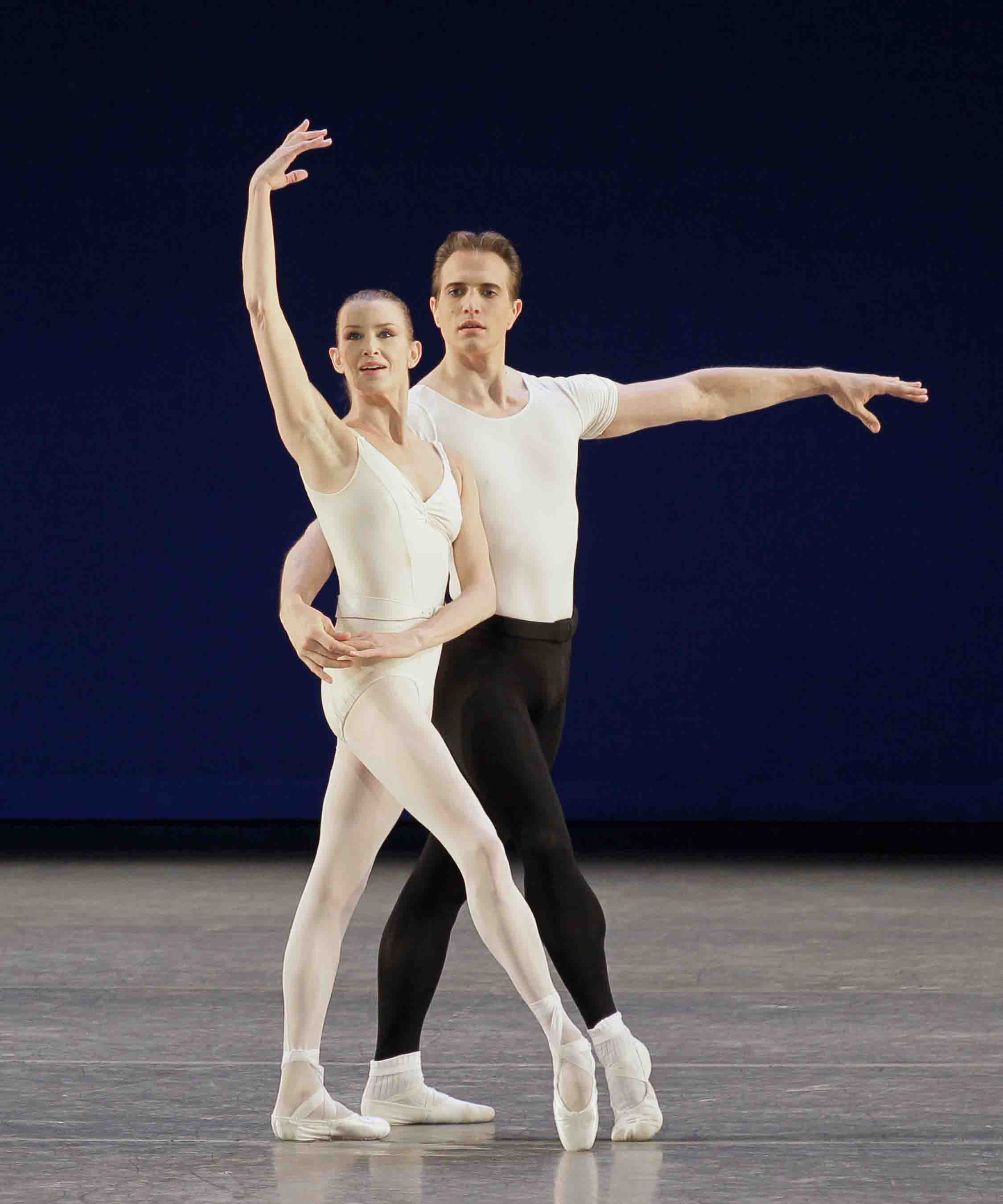

One Last Time: NYCB's Philip Neal and Jenifer Ringer in Balanchine's Serenade

Photo: Paul Kolnik

In his 22 years with the company, Neal was the model of the quiet authority that is earned through purity. His technique had a clarity that seemed to be bred in his bones. His demeanor was modestly reserved; he often seemed to disappear into the dance and was obviously unacquainted with the realm of "show biz." He cultivated "the plain style"--without excluding grace and elegance. This was evident even in small things: The movement of his hands and wrists, for example, had a loveliness abandoned by most men of his and the rising generation. Among his most significant gifts was his masterly partnering; he helped a ballerina's individual temperament bloom because she was secure in his arms.

For his final appearance, Neal danced the first-arriving of the two male leads in Balanchine's poignant Serenade, the ballet for which the twentieth-century's greatest choreographer thought he might, just might, be remembered, and the male lead in Balanchine's Chaconne,

Neal's dancing in Serenade, with Jenifer Ringer, was all tenderness, gravity, and regret. His deference to the presence and plight of the figure Ringer represented seemed to echo Balanchine's much-quoted declaration "Ballet is woman," the implication being that man (if the choreographer) is her servant or (if the dancing partner) her cavalier. Neal wasn't quite all-subservience, though. Dancing alone, for instance, he'd execute a high, wide leap, imprinting the image of his perfectly aligned body on the air so indelibly that he seemed, for a few seconds, fixed in space, while the air surged around him.

In Chaconne (to plangent music taken from Gluck's opera Orfeo ed Euridice), Neal and Wendy Whelan were equals as they danced first among the Blessed Spirits (an ever-shifting matrix of young women with flowing skirts and unbound hair), and then became the monarchs of a kingdom full of delightful if inscrutable protocols that only a scholar of early classical music or a child steeped in fairy tales could explain. As did the originators of their roles, Suzanne Farrell and Peter Martins, Whelan and Neal made the whole business cohere.

Toward the end of the ballet, Whelan, who seemed to be dancing with great joy, streamed all her focus in two marvelous solos toward Neal instead of to the public, expressing--spontaneously, I think--her affection for her longtime colleague.

It Was Roses, Roses, All the Way: Philip Neal and friends

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Then came the curtain calls: the Chaconne cast applauding the retiring star; Neal responding to Whelan with a real kiss; long, swirling silver streamers shot out of nowhere toward the hero of the hour. Next, the parade of former and current colleagues, bearing flowers. Among them were Kyra Nichols, now retired, Neal's most important partner in the course of his career; Albert Evans, due to give his own farewell performance one week hence (snappily dressed for the occasion, Evans kissed a single red rose before offering it to his buddy); and Darci Kistler (the last ballerina selected by Balanchine), whose farewell will come the following week and close the season.

Peter Martins joined the gang of Neal fans, as did many other members of the company. The "pedestrian" in the congratulatory crowd was Neal's partner, that gentleman's walk-on appearance being only suitable since, in recent years, ballerinas have been bringing their husbands and children onstage for similar celebrations. Little nosegays were flung stageward by admirers in the audience, and finally Neal stood alone on the carpet of petals, his posture recognizable from curtain-call photos of the foremost male dancers down the decades. Standing erect yet subtly sculpted, like a classical Greek statue, he held one hand over his heart--as if he meant it.

This last goodbye was touching--many in the audience wept--because it made clear as never before how important Neal's dancing has been to the company's profile. America doesn't hold with aristocracy and Neal's dancing is unmistakably American--plainspoken and without airs--but he is nevertheless a prince.

Farewells stir up memories. I first encountered Albert Evans offstage when New York City Ballet had recently promoted him, Philip Neal, and Nilas Martins to soloist rank and I was interviewing them as a group. When all the obvious points had been covered, the conversation turned casual and Evans mentioned, modesty barely veiling his pride, that he had just moved into a new apartment. "What style are you decorating it in?" I asked. I should have known there could be only one answer, and he came right back with it: "Albert Evans style."

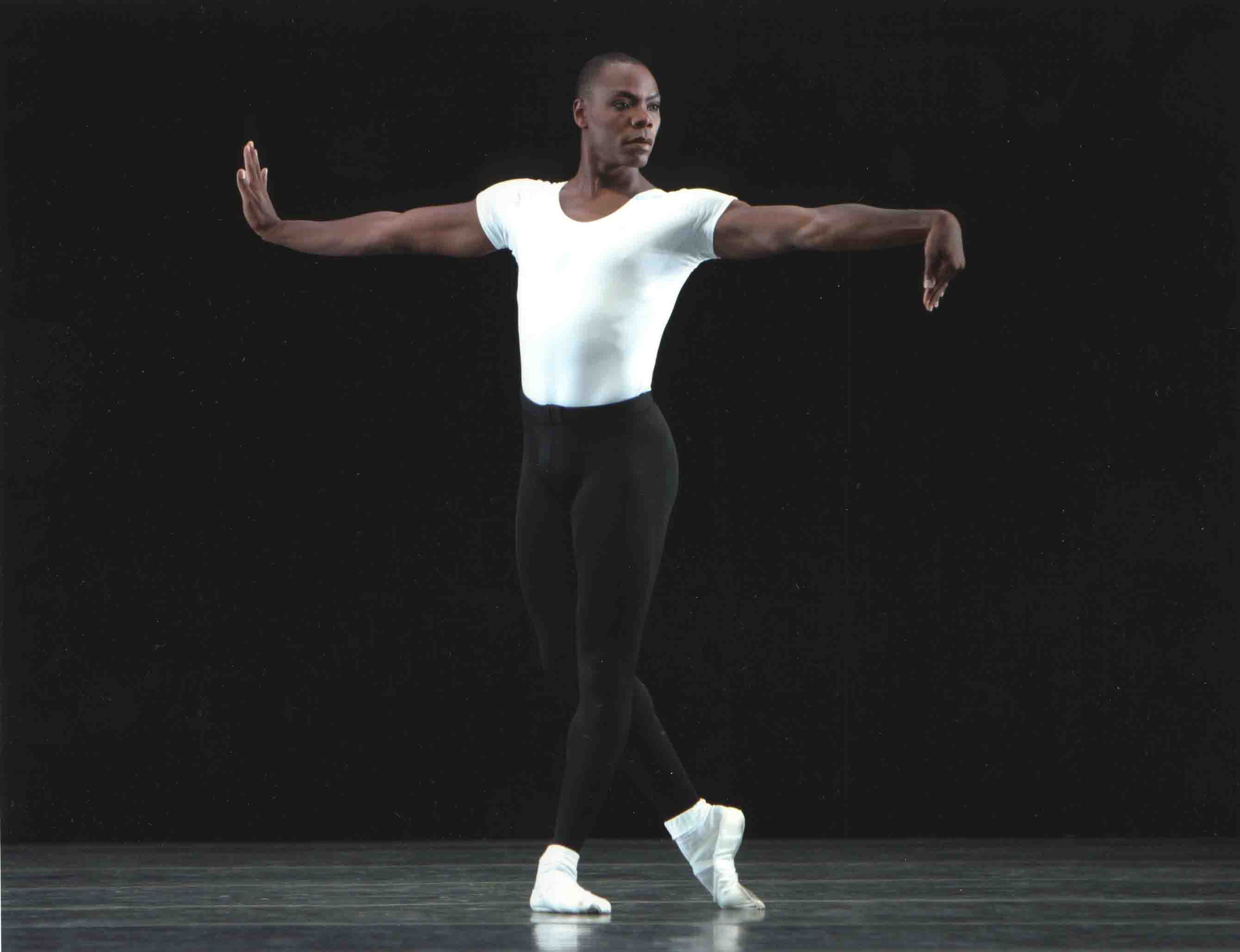

Phlegmatic: NYCB's Albert Evans in Balanchine's Four Temperaments

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Time passed. He danced. Evans was a beautiful classical dancer with an on-the-mark yet velvety technique. On appropriate occasions he countered its sheer beauty with streetwise alertness to possible danger--around him or within him. This profile, obviously welcome in contemporary choreography, gave an added dimension to Balanchine's work, especially the abstract "leotard ballets" that lie at the heart of the City Ballet repertory. In lighter works he gave his sunny personality free rein.

In 1995 the company elevated Evans to the top rank of principal dancer. He continued to dance. When a slew of new ballets was needed for one of City Ballet's periodic festivals, visiting choreographers vied to use him. He was an extraordinarily charismatic presence, and a showman par excellence. From the moment of his entrance he could persuade the audience that something compelling was going on.

Eventually, as happens to us all, but later, the body began to exact its compromises. On June 20, Evans danced his last performance with City Ballet, appearing in a rakish duet from William Forsythe's Herman Schmerman; Balanchine's Four Temperaments, a touchstone of neo-classicism; and a flower-filled, confetti-studded series of curtain calls in which he received an enthusiastic homage from his colleagues, who crowded onto the stage, and from the standing, robustly clapping, vociferously appreciative audience calling out his name.

Smilin' Through: Albert Evans and friends

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The two indelible moments in those multiple curtain calls were Evans's half-reclining on the floor behind the pile-up of bouquets as if he were a jokester mocking his own death and burial, assuring the spectators it was just a prank, and his standing and shedding his soft white ballet slippers (part of the danseur noble's uniform) and throwing them--as if to say "That's that!"--into the lush, soft-petalled mound.

Perhaps relinquishing performance at the highest level when you still have half your life to live has to be handled ironically to be endured. But, even if unintentionally, Evans had delivered another--ingenuously hopeful--message at the close of The Four Temperaments. As the parallel lines of the entire cast formed a runway for flight toward some unidentified but implicitly cosmic destination, Evans turned his head sharply away from the audience and into the wings as if he'd suddenly discovered something riveting in the distance and was moving straight toward it.

American Ballet Theatre's Sleeping Beauty is a scandalously inept version of the Petipa classic. Changes have been made to the company's current production since its premiere in 2007 in the hope of correcting this or that absurdity--choreographic, narrative, or decorative--to no avail. It's wrongheaded from the word go and a desecration of the Tchaikovsky score, of which it omits huge chunks because today's audience is assumed to have no sitzfleish.

Let's say, to be generous, that the people responsible for the production--Kevin McKenzie, Gelsey Kirkland, and Michael Chernov--fully appreciated the beauty of the traditional version of the ballet, understood its deep metaphoric significance (instead of confusing a fairy tale with realism), and had listened to what the music was clearly telling them at every turn. If so, they were simply unable to bring their knowledge to making a fresh version that a perceptive dance viewer could admire. I've stayed away from this Beauty since I reviewed its premiere and returned only to see the Royal Ballet's Alina Cojocaru and the Bolshoi Ballet's Natalia Osipova dance Aurora--matinee and evening respectively on June 19, at the Metropolitan Opera House.

Both ballerinas are small, slight women and, for a dancer, anatomy is in part destiny. If the petite dancer bubbles with energy, she's a natural for soubrette roles; one with more lyrical leanings seems born to arouse pathos.

Fish Dive: Alina Cojocaru and Jose Manuel Carreño in ABT's Sleeping Beauty

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Cojocaru certainly looks as fragile as a porcelain figurine, but I can't understand why she chose to portray Aurora largely in the pathetic mode. To be sure, there's a curse looming over this heroine, yet it doesn't seem to undermine the radiant ebullience the world's most unforgettable ballerinas have given her at her Sweet Sixteen party. (Aurora may not even know about the dark prophecy since, seeing a spindle for the first time, she finds it a fascinating toy.) And I suppose, when the Lilac Fairy reveals her to the Prince as an impalpable vision, there's some melancholy to be found in the notion (ignored in all the other interpretations I've seen) of Aurora's yearning for a love that seems infinitely delayed. But at her coming of age celebration (until the malicious Carabosse intrudes) and at her wedding, Aurora is triumphant, a young woman truly coming into her kingdom.

I imagine the quality Cojocaru is aiming for is reticence--an understated interpretation that would register as refined, elegant, and, in the end, touching. What I saw in her single ABT performance, however, looked dry and constricted--more repressed than refined, more thought through than danced through. No surprise, then, that this Aurora failed to delight.

This is not to say that Cojocaru's rendition wasn't technically superb. On the whole it was. And not just in the obvious places--the preternaturally sustained balances of the Rose Adagio and (thanks to Jose Manuel Carreño, a prince worth waiting for) perfection in the series of fish dives that climax the grand pas de deux of the Wedding Scene. Less obvious moments were equally gratifying. Take, for example, Aurora's traveling down a diagonal line of her kneeling suitors, pausing briefly before each one in arabesque, then descending seamlessly from full point to flat as, with a Japanese sense of propriety, she delicately shades her face from the men's view.

In the course of the past six years or so, I adored the dancing I'd seen from Cojocaru here in New York, with only slight and occasional reservations about a lack of full-blooded passion. In the Beauty performance I just saw--the ballerina's single appearance with ABT this season--I felt the balance had tipped in a discouraging direction. Cojocaru can't go back to what she once was--no artist can--but there's always the possibility of a heartfelt exploration of what one might be next.

The diminutive Osipova is the ballet world's young favorite and, at the moment, the general public's too, having emerged relatively unscathed after being mugged in the Lincoln Center nabe. Her performance of Aurora on the 19th was her very first in The Sleeping Beauty--anywhere.

Wedding Redux: Natalia Osipova and David Hallberg in ABT's Beauty

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

If the event wasn't an unqualified success, it's because she isn't the Aurora "type." Lacking both innate charm and radiance, she's not convincingly girlish in the birthday scene or able to project a womanly glow for the wedding scene. (Yes, these are old-fashioned qualities but Beauty is an old-fashioned ballet--and a keeper nonetheless.) There were many hints in Osipova's performance that she knows what the story and music require, but she can't produce these effects yet; they're still just ideas and they don't mesh with the personality her dancing regularly reveals. She's a hoyden--spunky and fearless, a cousin of Tom Sawyer and the heroine of Agnes de Mille's Rodeo, who wants to ride with the cowboys.

The gods know she applied all her stunning technical skills to the task. Leaping is Osipova's preeminent gift. She seems to rise up from nowhere and, as Nijinsky described his own uncanny elevation, "just pause in the air for a little before you return" or let herself be blown by an unchartable wind to another lofty niche in space. Just as her preparation for these amazing flights is invisible, her landings may be invisible too. At any rate, I've never noticed them.

She's a world-class turner too. I especially liked her supported pirouettes with the four princes come from afar to woo Aurora. With the first suitor she does a single pirouette; with the second, two, and so on. I've seen many a ballerina avoid this challenge, since it's tricky to keep the triple and quadruple pirouettes clear. Osipova, I suspect, could bring off the feat in her sleep.

And of course there are her sky-high extensions, breathtaking for those who like this sort of thing. I don't; they make the working leg look detached from the body, as is the case with even the most "realistic" jointed doll.

It's tempting to weigh Cojocaru's Aurora against Osipova's because of the circumstances under which one had to view them, both ballerinas appearing one time only in the role and on the same day. Thus you could find yourself saying, "Well, Osipova's balances were secure, but Cojocaru's outshone them" or "Cojocaru seemed willfully to have decided to damp down her interpretation, but Osipova may already be invested in the drama of Aurora's growth to maturity." Such remarks might be true but they're not very pertinent, dance being an art, not a competition, no matter what TV shows and those gold and silver medals propose. Besides, both Cojocaru and Osipova were outclassed by a model who is now hors concours: Margot Fonteyn.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Ballet Diary No. 6: American Ballet Theatre: All-Ashton Program; All-American program (ABT's season runs through July 10 at the Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC; New York City Ballet: Mauro Bigonzetti's Luce Nascosta, (NYCB's season runs through June 27 at the David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC)

Note: This is No. 6 in the series "Ballet Diary"--comments on the 2010 spring seasons of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, along with related performances. To read previous pieces in the series, click here: No. 1; No. 2; No. 3; No. 4; No. 5. The completed "Ballet Diary" series will comprise nine essays.

After giving the general public what marketing believes it craves--three weeks straight of program-length works--American Ballet Theatre gave hard-core (or is it old-fashioned?) dance aficionados a break with a week of mixed-repertory programs. Mind you, the mix was always governed by a specific theme, assuring the ticket buyer, by means of a label, that he or she was making a solid investment. I went to see the All-Ashton and the All-American programs.

Birthday Party: The full cast of Frederick Ashton's Birthday Offering

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Only half of the Ashton program offered a goodly amount of sheer pleasure; the rest was a demonstration of ABT's efforts to dance in a style foreign to it. Frederick Ashton's ballets are quintessentially English: On the surface many of them have a fairyland lightness--the exquisite grace of a highly mobile torso set against delicate, precise footwork; at the core lie feelings that pierce the heart.

ABT's rendition of Ashton's 1956 Birthday Offering made me think of the Advanced Placement exams taken by college-bound high-school students: an occasion to test their chops in a subject about which they've learned a great deal, but hardly everything they need to know for genuine mastery.

Created for the 25th anniversary of the company that had just received its charter as the Royal Ballet and set to deliquescent Glazunov music, the piece is danced by seven couples (one more equal than the others). The full cast opens the ballet with a promenade of the pairs, which then evolves into a group dance that still recalls the idea of a promenade. Ashton knows his trade and provides the obligatory elements of a formally constructed display piece--a duet for the chief couple and an ensemble dance for the men. But the astonishing core of this ballet is seven solos for the women, one after another, each ingenious and difficult in an a unique way. The difficulty is meant to be invisible--masked by the dancers' prowess. For this you need seven women of the highest technical caliber and individual distinction. I'd venture to say that ABT doesn't yet have the personnel equal to the task.

Still, the attempt was glorious. Usually, in the performing arts, nothing counts but first-class results, but here you could see gifted, proficient, and experienced dancers learning and trying, learning and trying. Their understanding of how Ashton's choreography should be danced, along with their persistence and humility, cheered me immensely. Those solos--an echo of Petipa's individual dances for the fairies at Aurora's christening--are still at the point where they're being executed step by step, a concern with correctness foremost. Rarely does the material expand into dancing that flows naturally, as if it were almost spontaneous. Could this facility come with time? Could ABT borrow a significant number of rehearsal hours from the production of new works that are no more than gimmicks and tomfoolery and, instead, spend them on the treasures of earlier decades--the Ashton repertory, the Tudor repertory, even the Balanchine repertory (with people to coach it merely a stone's throw away)? Classical choreographers of genius being almost non-existent nowadays, might this not be a perfect time to look to--and preserve--the glories of the past?

The Awakening pas de deux from Ashton's version of The Sleeping Beauty was basically a disaster area, apart from Paloma Herrera's making a timid but credible attempt at acting instead of merely dancing Aurora with her familiar technical panache. In Perrault's version of the fairy tale, the young woman says, immediately after her kiss-alarm clock rings, "Is it you, dear prince? You have been long in coming!" I hated to think of this 116-year-old (but nonetheless radiant) princess's having spent the previous century in the milkmaid-style nightie Herrera wore. The object of her instant affections (although Perrault slyly hints she may have glimpsed him in her dreams) appeared to be sporting the uniform of his soccer team. Played by Cory Stearns, he was not worth waiting for; Stearns lacks both the technique for Ashton's subtle but challenging choreography and the necessary dramatic presence.

Diana Vishneva's partner for the Thais Pas de Deux, Jared Matthews, was something of a cipher too, but Vishneva was utterly compelling as the veiled woman who comes to her worshipper as if in a high-minded--almost spiritual--version of an erotic dream. Deliberate and sinuous in her movements to Massenet's music, blank in her expression but fiercely concentrated, the Russian ballerina slowly drew in the audience with the kind of magnetic force there's no point in resisting. Through her portrayal Ashton preached his gospel, once again: Woman's power lies not simply in beauty, but in beauty that's coupled with mystery.

Faerie Grace: ABT's Gillian Murphy and David Hallberg in Ashton's A Midsummer Night's Dream

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Created in 1964, to Mendelssohn's delectable music, The Dream is one of Ashton's greatest triumphs and ABT did it justice, evoking Shakespeare's antic and romantic fairyland, forever entwined with the predicaments of mere mortals. The company's female ensemble succeeded in producing the effect of quivering butterfly wings, while the principals outdid themselves, dancing Ashton's choreography with both freedom and credible style, at the same time conveying the temperament of their characters.

Gillian Murphy, as Titania, was splendidly imperious and willful; David Hallberg's Oberon, quick to match her and quick to anger. Hallberg went all out in his dramatic interpretation, with passages of sublime authority (aided by his flawless technique, which combines lyricism with virtuosity)--and little moments in which he indulged in the refined fussiness typical of a dealer in high-end antiques. I can't imagine ever forgetting his Oberon's sudden flares of temper, his self-confident haughtiness, or his delivery of the long skeins of assorted turns that Ashton originally set for Anthony Dowell.

Murphy made much of the lust Titania has for Bottom, the workman temporarily transformed into an ass, pressing the long donkey ears to her breasts and deeply embarrassed when Oberon confronts her with her transgression. These passages provide an important contrast with the duet--surely one of the jewels of twentieth-century choreography--at the end of the ballet in which Titania and Oberon find their way to a perfect union. As exasperated feminists will assert, she succumbs to him, but Ashton makes it clear that she does so of her own will.

Ain't Misbehavin': ABT's Herman Cornejo as Puck in Ashton's Dream

Photo: Gene Schiavone

The twisting, high-flying motions of Puck is just another feather in Herman Cornejo's cap. This extraordinary dancer left his personal mark on the role by giving it a grotesque and servile tinge that was almost scary yet just right.

Julio Bragado-Young, as the transmuted Bottom, earns special mention for his point work. Without forsaking his masculinity, he delivered the unwavering line through the legs and the neatness of foot (hoof, if you will) that might be the envy of the girls in the advanced class of the company's school.

Encountered first in a flyer for ABT's season, the umbrella title "All American" for a ballet program seemed contrived to me. What difference could it possibly make that all three choreographers happened to be natives? All the difference in the world, as the performance proved. The trio of ballets--Twyla Tharp's Brahms-Hayden Variations, Jerome Robbins's Fancy Free, and Paul Taylor's Company B share the lustiness of purpose, the theatrical ingenuity, and the bravado needed to pioneer uncharted ground that are typical of American ventures. It helped, of course, that all three ballets are keepers.

For The Brahms-Hayden Variations, choreographed for ABT a decade ago, before Tharp became dangerously distracted by Broadway, 30 dancers assemble to create ever-shifting matrixes, the beautiful logic of which you sense, profoundly, even if you can't grasp--or even see--all of the marvels on a first viewing. Admittedly, this ballet is too dense--it's like advanced math, visualized--yet any little passage, or even phrase, that you do seize seems perfect for its moment in time and position in space. The piece has a crackerjack organization that's gravely formal even when what's going on step-wise seems decidedly peculiar.

As is her custom when operating in the classical-dance world, Tharp roots her choreography in the academic ballet vocabulary, but that's just a base. She takes every traditional move to the extremes she envisions for it, infiltrating the material along the way with borrowings from jazz, modern dance, gymnastics, pedestrian moves--you name it. Watching this dance, you feel blasted by possibility.

ABT's dancers stepped up to the challenges, eager and able. Despite a couple of tricky moments, they gave the piece the high-caliber performance it demands and deserves.

What's American about Brahms-Haydn? Tharp's self-invention and stubborn drive to push beyond what we already know; the polyglot nature of her dance language; her belief that complexity needn't be abstruse but, actually, fun.

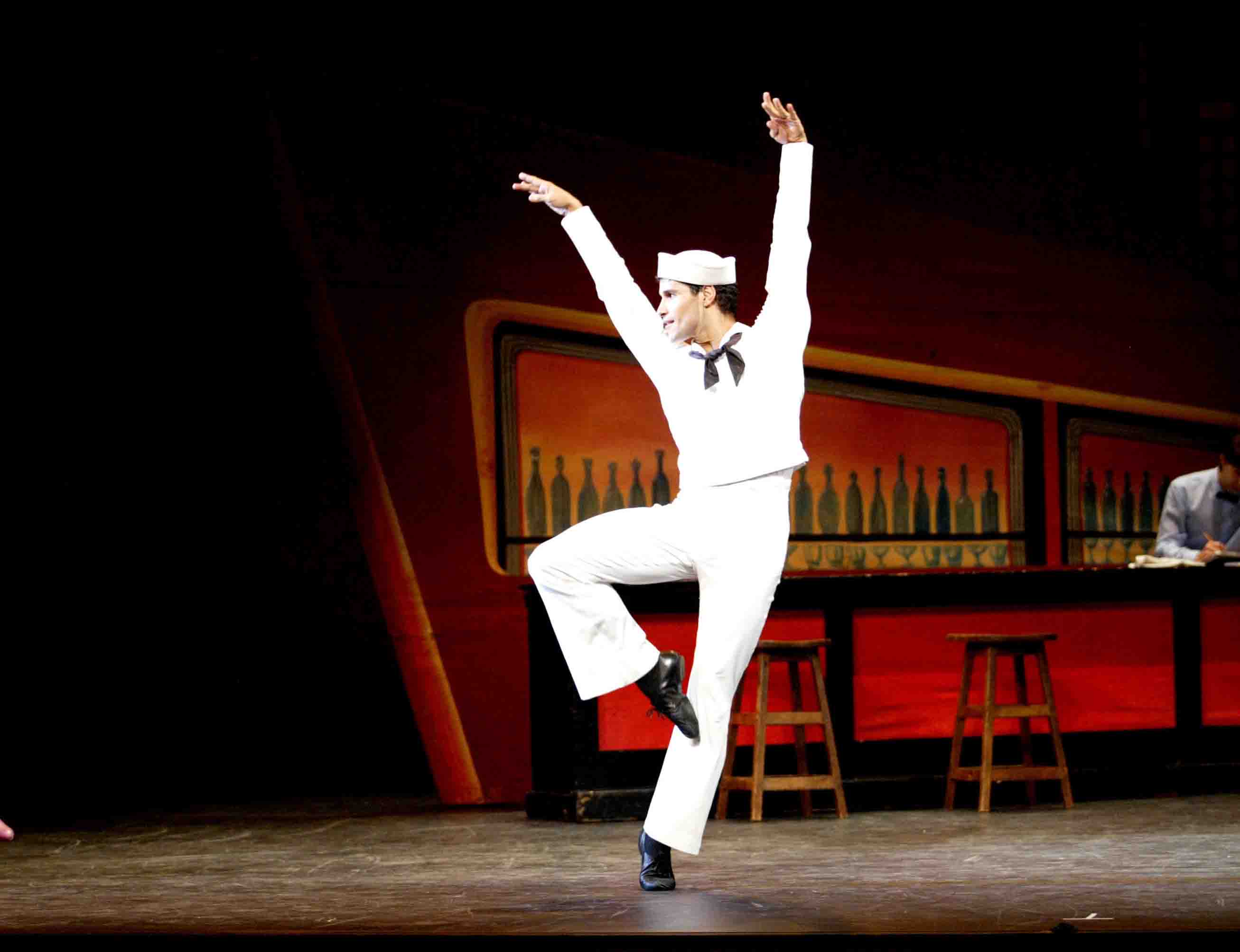

Ocean's Motion: ABT's Jose Carreño in Jerome Robbins's Fancy Free

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

An instant hit in 1944, Fancy Free, a collaboration between Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein, is one of the rare ballets that tells a story but needs no libretto. It's perfectly clear and perfectly wonderful. Three sailors--fast friends--on shore leave in the big city, on the lookout for dates. One, then two gorgeous prospects stroll by. After a sassy encounter, then a tender duo the question remains: How to divvy up these terrific femmes? All five repair to the corner bar (the brilliant set showing both sidewalk exterior and watering-hole interior is by Oliver Smith) where each guy struts his stuff in a solo revealing his temperament: poetic; athletic; sexy. The competition being inconclusive, the guys naturally resort to fisticuffs. The girls depart in a huff. Bereft, the sailors reconcile under the street lamp, ruefully accepting their failure with the fair sex, until . . . Just before the curtain falls, gorgeous prospect number three strolls by, and they go chasing after her, full-speed.

Having watched Robbins teach Fancy to New York City Ballet dancers--the sessions included consulting a film of the original cast--I can guess that the choreographer's well-known obsession with accuracy down to the last detail has played a major part in the ballet's surviving its transmission to several generations of dancers pretty much intact. The ABT cast I saw this season produced not only the steps and gestures but also--equally important--the personalities of the characters, even to the incredibly beautiful blonde walk-on, who may provide the shortest description ever made of the term narcissist.

Best of cast prize goes to Jose Manuel Carreño, who does the solo originally danced by Robbins himself. It was inspired, Robbins has said, by the sight of a sailor dancing in a bar, his arms wrapped around a chair in lieu of a flesh-and-blood partner. In the choreography, the chair is gone and the arms embrace empty space (enticing the imagination), but the rhumba's swiveling hips are definitely there. Carreño adds his own seductive personality.

What's American about Fancy? It gives us the U.S. of A. in a nutshell--a land of good-natured dreams about youth, buddies, easy pick-ups with no dire consequences (indeed, no consequences at all), and living contentedly in the moment (even if there's a war going on). Some of those dreams have corroded in the last sixty-six years, yet the ballet remains effective and beloved.

Like Fancy, Paul Taylor's Company B, created in 1991, refers to World War II. It's danced to recordings of the Andrews Sisters' irresistible pop songs and, though its men are in mufti, often dancing ebulliently with sweetie pies in bobby-sox, from time to time they march in silhouette behind an upstage scrim, shooting and falling. Towards the end of the ballet, the war impinges directly on the world of upbeat spirits: The irrepressible antics of the bugle boy are quenched with a single bullet and a woman mourns the death of her soldier husband, acknowledging that while life will go on for her, he will never be replaced in her heart.

ABT gave the work a cast largely composed of artists who can play down-to-earth people; no one on stage seemed to be longing for roles as impalpable spirits, abstract choreography, or point shoes.

What's American about Company B? As with Fancy, the picture of a memorable era in our country's history--this time created in retrospect and letting the dark veil the light. The jitterbug moves, all the rage in the Forties, that Taylor embeds into his modern-dance choreography. The absence of swans.

Cater-corner from the Metropolitan Opera House, at the David H. Koch Theater, New York City Ballet presented the premiere of Mauro Bigonzetti's Luce Nascosta (Unseen Light) on June 10. The sixth of seven new works the company has commissioned for its "Architecture of Dance" festival, the ballet has music commissioned from Bruno Moretti, a frequent Bigonzetti collaborator, and an overhead--in the middle, mercifully a good bit elevated--sculptural installation by Santiago Calatrava, who has been the festival's architect in residence, so to speak, available for the new works.

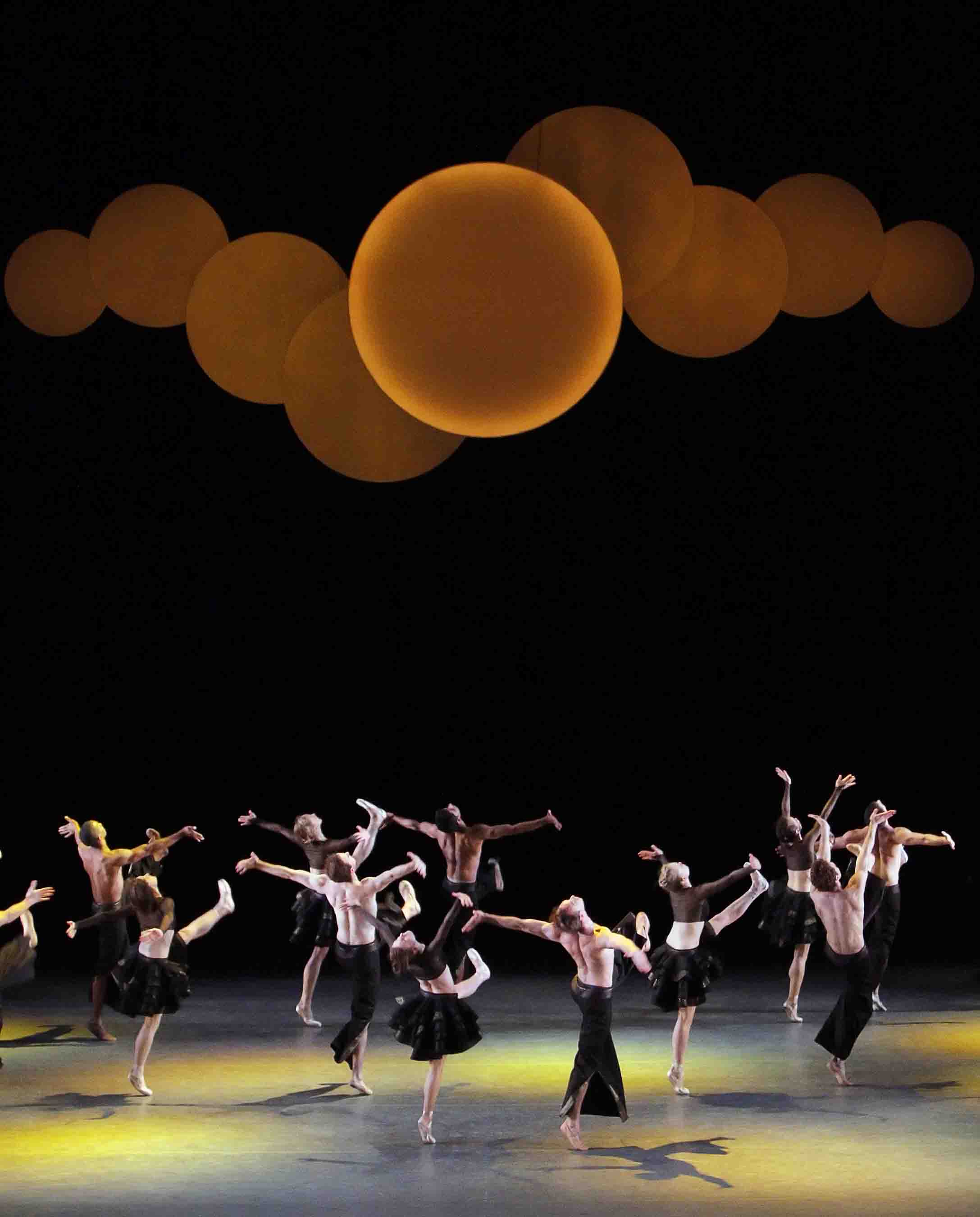

Darkness at Noon: NYCB dancing Mauro Bigonzetti's Luce Nascosta. Installation by Santiago Calatrava

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The piece opens with figures barely visible on the darkened stage. Above them hangs Calatrava's contribution, a glowing, bronzed sun that, in the course of the dance, will extrude several baby suns to either side, then gather them back, hinting at some metaphoric significance that's never defined. As the space grows marginally less dim, a couple dances what looks like a jagged version of an apache duet, the steps and rhythms skewed, as if taunting classical-dance harmony.

Actually the dancers' costumes are the first thing that strikes you. The men are bare-chested, with supple black trousers given a boot cut gone wild, splitting the garment's seams from the calf down. The women are bare-midriffed. You might suspect that the fabric thus "saved" is then re-purposed to give them their long, skin-tight sleeves. Most prominent are the ladies' short, black, extravagantly ruffled skirts, which suggest the plumage of an exotic bird. (Later, when the spectacularly long-legged Teresa Reichlen performs her solo of distortions, using her glutes to thrust her skirt out behind her, she resembles an ostrich. A charming ostrich, you understand.)

Clothes Encounters: Adrian Danchig-Waring and Teresa Reichlen in Luce Nascosta

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Anyway, by the time you've taken in the initial maneuvers and sized up the costumes, the full cast forms a double horizontal line, women foremost, the men stalking them. They look like a Spanish-style chorus line preparing for stardom in Vegas. Singled out next is a woman (Ashley Bouder) whose face is nearly hidden by a stylish loose bob. She seems to be the comedian of this errant troupe--though you must understand that nothing about Luce Nascosta is in the least funny--so after a peculiar solo she gets to do a grotesque pas de deux. Now and then, the men execute bits of gesture from Indian dance--maybe to indicate the power of ritual, maybe in homage to Maurice Béjart.

Well, you don't need to hear much more about the goings on. They remain simultaneously pretentious and tawdry--until Moretti's score changes its disjunctive tune (duly larded with festive scraps of "world music") and grows sentimental and sappy, as if for the happy ending of a pre-Sixties romantic movie. The population duly takes its cue and manages to move, halfway anyway, to a less fraught life style. For me, the endless reconciliation passage, with the women skidding on point into their partners' arms, was the last straw.

To distract myself from my dismay at the cheap aesthetic (if that's the word) of Luce Nascosta, I tried to grasp what the ballet is "about." I concluded, half-heartedly, that it deals with the sexual mores of foreign climes that are too weird for us--not being Margaret Meads--to understand, but not too weird to titillate us. Then I realized that I have never once wondered what Balanchine's Concerto Barocco is about.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Ballet Diary No. 5: School of American Ballet Workshop Performances / January 5 and 8, 2010 / Peter Jay Tharp Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC

Note: This is No. 5 in the series "Ballet Diary"--comments on the 2010 spring seasons of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, along with related performances. To read previous pieces in the series, click here: No. 1; No. 2; No. 3; No. 4. The completed "Ballet Diary" series will comprise nine essays.

Aspirants: School of American Ballet students in Christopher Wheeldon's Scènes de Ballet

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The School of American Ballet is in the top echelon of conservatories that train promising young people for what the great 19th-century Danish ballet master August Bournonville remembered his father calling "the most glorious career in the world." At its annual Workshop Performances, the school presents a selection of its students in a program that almost always features choreography by George Balanchine, since SAB is, after all, the official academy of New York City Ballet. This year was no exception. In three performances--two on June 5, one on June 8--students for whom high school is merely an extra-curricular activity gave spirited renditions of Balanchine's Valse Fantaisie and Bourrée Fantasque.

Staged by Suki Schorer with her customary élan, Valse Fantaisie (to a now lively, now romantic Glinka score) was the most wonderful item on the program. A pair of lovers accompanied by a quartet of women sweeps through the space swiftly and lightly, creating a vision of the exuberance that may accompany joy--especially in the young. The women's pale tulle skirts waft behind them as they leap, swirl around them as they turn, making you think of clouds sent scudding across the sky by the breezes of a perfect spring day.

Attending the matinee and evening showings on June 5, I saw two different casts of principals, all four dancers being adequate and interesting. Both men, Peter Walker (born buoyant) and Spartak Hoxsa, were suitably limber and fleet, very likely destined, by anatomy and perhaps temperament, for "dreamer's" roles, such as James in La Sylphide and the Poet in Les Syphides. Physically (and, no doubt, emotionally) they have some years of growth ahead of them, but they've been given all the right ideas about dancing--moving on a large scale, cleanly and with assurance, leaving uncertainty and affectation behind.

Claire Kretzschmar, Walker's partner, was thoroughly musical, with a lovely leap. She looked as if she were effortlessly clearing hurdles made of whipped egg whites, knowing the hurdle couldn't hurt her if she failed and crashed into it and knowing, too, that she'd never fail. Hoxha's partner, Bianca Bulle, was very competent and self-possessed; she does need to relax her face, though, so that her beauty is not a weapon but an invitation.

Windswept: SAB students in Balanchine's Valse Fantaisie

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Schorer was unquestionably the most significant contributor to the production. Under her staging and coaching, the dance seemed to be exuded on a single breath. Eliciting your rapt attention from the very start, it appeared to take no time at all; when it ended--its spell broken by the familiar ritual of applause, bows, flowers--all you wanted was to see it again.

Susan Pilarre's staging of Bourrée Fantasque was fine, apart from an exaggerated emphasis on the quirkiness of the angled, off-balance moves of the first section. These are rakish enough without the performers pushing the point home. Otherwise the dancers' youthful vitality was exhilarating, both here and in the third movement, a Broadway-worthy finale that assembles the ballet's full cast and has them doing things like space-cleaving leaps in large crisscrossing phalanxes. If Workshop's dancers lack the gift of stillness, which would make the fireworks, by contrast, even more dazzling, it's simply because of their age. Only one of them has turned 20; they will acquire composure as they mature.

The middle section of the ballet is romantic and enigmatic; Chabrier's score creates--perhaps even indulges in--the mood. In a dream-world ballroom, ravishingly dressed in midnight colors (thanks to Karinska's original designs), a yearning man and woman continually thread their way through an ever-shifting maze of eight undifferentiated women (representing Fate, perhaps). The would-be lovers lose, find, and lose each other once again. And again. As it's presented here, the situation is so generic, I've often wondered if Balanchine, much given at times to the theme of doomed love (Serenade, La Valse, Scotch Symphony), was possibly being ironic here, suggesting that, absent a subtext, he could produce this sort of material by the yard.

At Midnight: SAB's Jillian Harvey and Chase Swatosh in Balanchine's Bourrée Fantasque

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Jillian Harvey was stunning as the quietly impassioned woman in this section. There is nothing in her build or technical strength that guarantees she'll be a leading dancer one day. It's her perception of who she is in this role that is so striking and so moving. She's made a story for her character--or, at the very least, taken her coaching deeply to heart--and this story suffuses every move she makes. Though it is not told outright, it fires our imagination. Harvey may never become a ballerina, but she is already an artist.

The two Balanchine ballets--neither of them, mind you, thought to be among the choreographer's most significant achievements--made Christopher Wheeldon's ponderous and self-conscious Scènes de Ballet, which opened the Workshop program, look as if its maker belonged to a lesser order of dance creators.

Wheeldon's ballet, originally made for the Workshop Performances of 1999, borrows its name from the Stravinsky score to which it's set. It aims to depict the development of a classical dancer from childhood to the cusp of professional status. It's a very prettified version of the tale, which I found saccharine though others will undoubtedly think it charming.

The ballet's heavy décor suggests a studio in old Russia--a reference, perhaps, to Balanchine's beginnings--and uses twin ballet barres that stretch diagonally down the stage floor to indicate the partition between reality and mirror image, an ever-present factor in a dancer's life. Just about all the ensuing choreography respects this divide and maintains the old theatrical device of having two dancers seem to be just one body and its reflection.

Wheeldon exploits the endearingly tiny, fragile look of the youngest children, opening with a pair of girls in pastel tunics who probably haven't yet learned their multiplication tables. To these wisps of promise and possibility he methodically adds, level by level, pre-teens, teens, and fully developed late adolescents about to sign their first contracts. He arranges this youth squad in studied, picturesque displays, all necessarily involving the imaginary mirror that bisects their space. A few of the formations are clever, even appealing; however, there is no room for real dancing to be going on. What's more, while the hierarchy of the bodies of different ages and degrees of mastery is clear, the very spirit of dancing is ignored.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Ballet Diary No. 4: New York City Ballet: Christopher Wheeldon's Estancia (NYCB's season runs through June 27 at the David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center); American Ballet Theatre: John Neumeier's Lady of the Camellias; Don Quixote; Alicia Alonso's 90th Birthday Celebration (ABT's season runs through July 10 at the Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center)

Note: This is No. 4 in the series "Ballet Diary"--comments on the 2010 spring seasons of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, along with related performances. To read previous pieces in the series, click here: No. 1; No. 2; No. 3. The completed "Ballet Diary" series will comprise nine essays.

If you want to revel in evocations-of-the-untamed-land, go to Willa Cather's My Ántonia or raid the kids' bookcase for Laura Ingalls Wilder's "Little House" series. Do not, for love of Terpsichore, consult Christopher Wheeldon's latest effort, Estancia, for New York City Ballet's "Architecture of Dance" season.

Horseplay: Christopher Wheeldon's Estancia for NYCB

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The piece, which had its premiere May 29 at the David H. Koch Theater, is named for a score commissioned from the Argentinean composer Alberto Ginastera by Lincoln Kirstein for Ballet Caravan, one of the forerunners of City Ballet. George Balanchine was to have provided the choreography but the little company folded before he set to work and the music, composed in 1941, wasn't given a dance realization in the States until Wheeldon came along.

The title of Ginastera's score, which Wheeldon co-opted for his ballet, means ranch. And that's where Wheeldon takes us--to Argentina's Pampas, a landscape that features dizzyingly wide horizons to which one gazes across enormous stretches of untrammeled space and mettlesome people who live close to the earth. Wheeldon's treatment lends the gauchos (something like America's cowboys) a pack of wild horses instead of more prosaic individual mounts. It can't fail to remind audiences of Agnes de Mille's Rodeo, which conjures up our western plains, their settlers' bond to its wide horizons, and, for the men, a life on horseback.

Estancia tells a story derived from Ginastera's own synopsis and a poem--about the beauty of the simple life--that inspired him. A city boy (Tyler Angle) yearns to become part of the rural workers' domain, identifies a potential sweetheart (Tiler Peck) there, is rebuffed by her, then accepted when he tames one of the natives' wild horses. Midway through this unlikely scenario, a group of city folk, thinking themselves superior because they're urban, insult the locals as they try to lure the young man back to town. The two sectors reconcile so the ballet can end with a lusty dance of celebration.

Here's where Wheeldon goes wrong:

(1) Everyone in Estancia--human and equine alike--moves like a highly trained ballet dancer, the women on point. Even the formal stage patterning recalls conventional classical ballet. This doesn't help the viewer imagine the down-to-earth beauty of life in the Pampas.

(2) The Horses: Humans as horses are tricky. Ballet dancing humans as horses--lavish manes and tails whipping about a vertical body--are ludicrous. Four mares (on point) in a bit of pas de deux-ing with a quartet of gauchos are beyond the pale. Wasn't their lone stallion (Andrew Veyette, undeterred by absurdity) enough for them? As for The Boy's getting reins on the most slightly built mare and thus winning The Girl, the taming is a non-event, both physically and dramatically. Maybe Wheeldon should have had The Boy tackle the stallion to create a more striking, evenly matched contest.

Sweethearts: Tyler Angle and Tiler Peck in Estancia

Photo: Paul Kolnik

(3) The Girl of His Dreams: She starts out as feisty as they come, a role model you'd want for your goddaughter. But the moment she begins to reconsider The Boy as a romantic partner, she starts to melt into sweet, soft sentimentality. The couple's love duet, which ends with their cuddling on the floor, is so generic and sappy as to be embarrassing.

(4) The Singer: A distinguished baritone (Philip Cutlip) performing in operatic style--in the Pampas?

(5A) Class Conflict: Wheeldon's depiction of the snobbish city folks is simply too crude: ladies of the Forties dressed for visiting outlying districts--hats, gloves--being disgusted by horse droppings, and so on.

(5B) Class Rapprochement: Every musical-style show needs an upbeat finale, so rural and city folks unite for a generic display of joy, waving red bandannas. If Wheeldon is being ironic here, lovingly parodying old-time Broadway musicals (as, say, Alexei Ratmansky might), he's changing his tune too late in the game.

I don't blame the dancers. Even if the ensemble occasionally seemed half-hearted, the leads, Peck and Angle, gave the material their all and Veyette retained his self-contained visceral power (to say nothing of his dignity) in his peculiar assignment. Nevertheless, Estancia ranks high among the dopiest ballets I've ever seen.

The décor for Estancia--mainly a jazzy front cloth and a blurry backdrop giving a domesticated impression of the Pampas--is by Santiago Calatrava, whose scenic treatments are supposed to be the lynchpin of the City Ballet's "Architecture of Dance" festival. He does far better work designing buildings. Carlos Campos created the costumes--from the outré equine disguises to outfits for the city folk that focus more on period detail than on theatrical impact. The Boy, for instance, initially wears a business suit and tie--complete with tie clip.

I've been a sucker for La Traviata, the Verdi opera, since I was in my mid-teens. I fell for Camille, the Garbo movie, shortly thereafter: Oh, that ivory, arching throat! Oh, the wrenching pathos of the story! Oh, those ravishing Adrian outfits! I succumbed to the heady extravagances of Marguerite and Armand, Frederick Ashton's vehicle for Fonteyn and Nureyev, because of its dramatically potent stars and because only Ashton could have understood these artists so well. I even read--in the original French, no less--La Dame aux Camélias, the Alexandre Dumas, fils, novel that inspired the theatrical versions of the story. So of course I showed up for ABT's company premiere of John Neumeier's 1979 Lady of the Camellias. Twice.

Ill-fated Love: Diana Vishneva and Marcelo Gomes in Neumeier's Lady of the Camellias

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Obviously a good bit of this tale is impossible to realize through dancing. How, for example, is a spectator supposed to know the contents of portentously delivered letters and a diary? Neumeier refuses to admit that written text and human movement in space don't employ identical means of expression. He has a slew of other problems as well.

He loves to tell a familiar tale from an unusual perspective. In Lady of the Camellias he manipulates the narrative's time frame. The ballet opens at a postmortem auction of Marguerite's possessions, with all the key elements of the story told in flashback and--or so the program note claims--from the various points of view of the three main characters. (Neumeier, like William Forsythe, makes himself understood more clearly through program notes than via what he sets on stage.)

What's more, Neumeier can't resist complicating matters. His ballet follows the suggestion of the Dumas novel and draws a parallel between Marguerite's fate and that of Manon, told in the Abbé Prévost's 18th-century novel of that name and later popularized through the eponymous opera by Massenet and the ballet by Kenneth MacMillan.

Of course if Neumeier didn't make so much of the Manon story and if he cut out all his ballet's padding--most of the ensemble work is mere window dressing--all he'd be left with is a one-act show. Perhaps this is as much as the core story needs, or so Frederick Ashton demonstrated.

Further complaints: Neumeier likes to combine the realities of everyday life with "artistic" fantasy. While he constantly juxtaposes the two modes, he never succeeds in getting them to blend naturally. The Manon business, for example, starts as a ballet within a ballet, which Marguerite attends, and extends into the realm of the hallucinatory when the figures actually invade her life. Neumeier gives this transformation stock treatment so banal that it's unlikely to persuade the most credulous viewer to suspend his disbelief.

Courting Death: Vishneva and Gomes

Photo: Gene Schiavone

And then there's the TB element, perfect for Neumeier, whose work so often dwells on the association of erotic desire and death. He takes his titillating morbid streak to macabre extremes here, with simulated sex punctuating the heroine's wasting away and dying at tedious length.

As for the choreography per se, most of it is boiler plate, the ensemble work especially. But then there are those lifts. The ballet's many intimate duets are rife with them. Up and around and upside down or twining like vines overdosed on Vigoro. They're often awkward even when they come off as planned. When they don't, quite, you fear for the dancers' life and limbs. The worried spectator, noticing the near misses, is unlikely to understand the lift as ballet's ultimate expression of ecstasy.

Of course the spectator has other matters to distract him. If, when listening to the score Neumeier has culled from Chopin's piano works, both solo and accompanied, he recalls the choreography made to some of the same pieces by Robbins (in Dances at a Gathering) and Ashton (in A Month in the Country), he will have grave reservations about Neumeier's skills. The fact that The Lady of the Camellias coarsely parodies Robbins's choreography for the climactic "Grand Valse" of Dances at a Gathering hammers the final nail into Neumeier's coffin.

Given the weaknesses of their material, the dancers worked hard for a credible interpretation of their roles and did their courageous best with passages that should earn them danger money.

It's hard to know which is the more riveting--Diana Vishneva's technical prowess (the articulate footwork, the fluidity, and so on) or her unflagging investment in a narrative ballet's story and the life of the character she plays.

No, she's not magical; she has no "perfume." But she's so very good at what she does that you've got to admire her--even, as her hordes of fans do, love her. As Armand's stern father slowly and touchingly recognizes, Vishneva's Marguerite is a courtesan with soul.

For reasons best known to himself, Neumeier has choreographed Armand as an awkward wimp. Mercifully, the fellow stops bumping into things early on as he explores the naughtier venues of yesteryear's Parisian high life, but it takes a while before he stops throwing himself at Marguerite's feet--literally as well as metaphorically. Marcelo Gomes--an imposing, solidly built, darkly handsome guy whose dancing is uniquely forceful and self-possessed--is not the man for this role.

Both artists were nevertheless superb at portraying the moments in which Marguerite's flirtation and Armand's infatuation turn into soul-stirring love, the kind that's supposed to defy death or at least--in the fantasy realm of ballet, anyway--earn the couple an apotheosis.

Fatal Attraction: Roberto Bolle and Julie Kent

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Julie Kent and Roberto Bolle gave the leading roles a different cast and were more believable as a pair. Bolle's lanky raw-youth looks made his seeming innocence and initial haplessness convincing (though I don't know that the implied disparity of age between his Armand and Kent's Marguerite was part of the original story). Given his height, harmonious proportions, and charming face, Bolle has inevitably been trained to play princes; you can see him aiming for purity in his every move. As for feeling, he seems to be striving to follow every bit of coaching he's been given. He doesn't act from his own heart yet, but his efforts alone are disarming.

Kent has spent the latter part of her long career expanding her ability to act. This has stood her in good stead in the last decade and does so again in her portrayal of Marguerite. At first she appears harder and more glittering than the vulnerable characters she plays so tenderly--so often and so well. From then on, she slowly reveals the progressive ravages of Marguerite's illness, which go hand in hand with the deepening of her love until she seems to be a near corpse, kept alive only by passion. This effect is not simply something that can be taught or learned; it's rooted in a charismatic quality one is born with. No matter how hard he tries, Armand can't get Kent's Marguerite out of his mind--and neither can her audience.

Apart from its exquisite vision scene, ABT's version of Don Quixote--the venerable faux-Spanish crowd pleaser originally by Petipa (jazzed up by Gorsky)--is efficiently circusy, but largely without feeling. On June 1 it served as an ideal showcase for the Bolshoi Ballet's young wonder, Natalia Osipova, who is gradually building a guest-artist relationship with the company.

Forget Cervantes: Natalia Osipova and Jose Manuel Carreño in ABT's Don Quixote

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

As Kitri, the heroine of the piece, she made a flamboyant leaping entrance, slicing the air before her, sailing through it as if aided by a tail wind. Incredibly--I guess you had to be there, to see it for yourself--the afterimage she left wasn't at all assertive but rather buoyant and fleecy.

As the ballet progressed, Osipova repeatedly displayed her uncanny balance, perching on point on one leg while her free leg proved to be equally comfortable flung up high as if reaching toward the heavens, stretching to the side like an implacable road sign, or curved behind her, parallel to the floor. No matter what extravagant sculpted shape the choreography demanded, she remained poised, relaxed but unmovable, for seconds that seemed like forever.

If this weren't enough, she proved again and again that she has the gene for turning. Either you've got it or you don't; Osipova's a human gyroscope. In her rendition of the third act pas de deux, often given alone as a party piece, her execution of the infamous 32 fouettés (fierce whipping turns rooted to a single spot) suggested that the feat might well be retired until a new generation of dancers beats her alternating double whirls with singles--all produced with an aplomb suggesting she could probably up the ante to 64.

Interestingly, while most ballerinas play Kitri as a soubrette, Osipova, with her prodigious energy and her lack of sensual allure, made her a hoyden. When she hurls herself cross-stage, as horizontal as a flying bullet, confident of landing happily in her partner's arms, you see that daring is her sole charm. She's as brave as they come. And she could count on the catcher--Jose Manuel Carreño, playing Basilio, Kitri's Mr. Right.

Carreño had splendid feats of his own to display, the most marvelous being multiple pirouettes from a single preparation in which the pointed foot of the working leg snakes down from the knee to the ankle of the rotating leg and, by the final turn, has the toes tracing a circle on the floor, like the pencil of a compass.

Still, so much about Carreño's appeal as a dancer comes from his personality: the sweetness, the modesty; the undercurrent of erotic possibility; the masterly partnering that's based on a keen awareness, at every moment, of his ballerina's needs. His temperament shows up in all of his roles. It's perfect for dancing Basilio with an electrifying technician goading herself on to even greater achievement. Carreño doesn't try to dominate Osipova or compete with her; he enables and sustains her. His Basilio seems to be saying to this Kitri, Everything I do is for you.

Subsidiary Players:

Daniil Simkin--small, blond, and bare-chested--hit the air like a hand grenade in the Gypsy Camp scene that opens Act II. His role provides theatrical contrast to the romantic atmosphere of an exotic world at twilight. Simkin delivered ballet steps expanded, phenomenally, as if by an Olympics-grade gymnast. The effect was stupefying, thrilling, and grotesque.

Tiny, precise, and swift, finger coyly crooked to chin, traveling cross-stage with bourrées like a string of seed pearls, Yuriko Kajiya stole the Vision Scene as Amour (Cupid). The crispness of her dancing helped her avoid the cuteness endemic to this cameo role.

Victor Barbee, ABT's Associate Artistic Director, enhanced the entire production with his intelligent portrayal of Quixote--a frail, tattered old man undaunted in the pursuit of his ecstatic visions.

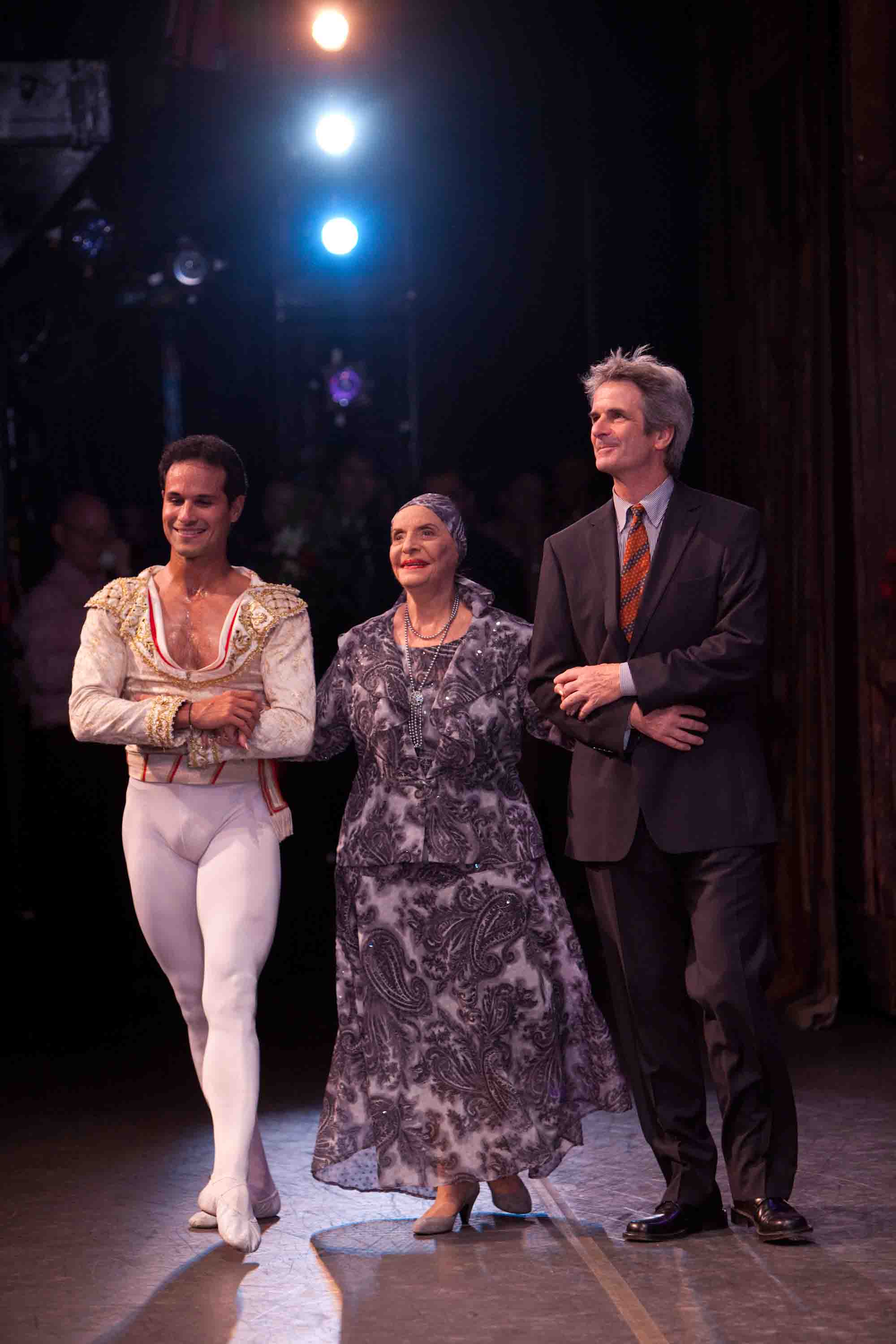

Grande Dame: Alicia Alonso, flanked by Carreño and McKenzie

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

Don Q was performed again on June 3 for Alicia Alonso's 90th Birthday Celebration with a different pair--Paloma Herrera and Marcelo Gomes, Xiomara Reyes and Herman Cornejo, Osipova and Carreño--leading each of the ballet's three acts. The Cuban-born Alonso, who blended sizzling technique with dramatic power and lyric eloquence, became a star of Ballet Theatre and then returned to her homeland to found the National Ballet of Cuba. Her dependence on the support of Fidel Castro gave her American admirers political qualms and her own uncompromising dictatorship over the company she brought into being against all odds frustrated the younger generations of dancers she bred. Still, she was a great artist and a woman of amazing courage, working half-blind through most of her career and dauntlessly pursuing her seemingly quixotic vision of a Cuban base for classical ballet. The dance world owes her a tremendous debt.

The celebration opened with a recent filmed interview interspersed with photos going back to Alonso's childhood and film clips of her clearly remarkable dancing. The interview, which occasionally caught her close to tears, is filled with potent one-liners. Obeying medical advice on healing the detached retinas that ravaged her sight, she recalls, "I spent one year in bed, and I danced with my mind." She refers to ballet as "the thing I love most in my life" and concludes with a rhetorical question: "Don't you think that beauty and happiness of life is better to fight for than war?"

The film was followed by Alonso's rising in the auditorium's center box to accept the audience's standing ovation. When the performance concluded over two hours later, Carreño and McKenzie escorted her onstage. There she received a lavish bouquet; the applause of the ballet's entire cast, which had assembled behind her (leaving a respectful gulf of space between them and her); and a gentle shower of confetti wafting down from above. She wore the most ravishing evening dress--all filigreed steel gray and the palest of blues--somehow glinting in the bright light that was beamed at her. The most powerful women in Europe and the Americas would do well to ask her the name of her dressmaker.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary