Seeing Things: April 2010 Archives

Ballet Diary No. 1: Introduction to Ballet Diary series; New York City Ballet: Opening night gala / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / April 29, 2010

Year after year New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, the kingpins of classical dance here in the States, insist upon competing with each other at Lincoln Center. As springtime slips into summer, the two troupes play mostly overlapping seasons--this year, eight weeks each--at abutting theaters (City Ballet will be at the David H. Koch, April 29 - June 27; ABT, at the Metropolitan Opera House, May 18 - July 10). How's a dance critic to cope? Perhaps taking the easy way out--though any other arrangement I devised seemed artificial--I decided that this year I'd cover the scene with a ballet diary, describing and commenting on the lavish procession of events weekly or bi-weekly. Let's hope this works. No aspect of a life in or near dance comes with a guarantee.

With its opening night gala on April 29, New York City Ballet inaugurated a blockbuster eight-week season. Under the umbrella title of "Architecture of Dance: New Choreography and Music Festival" and honoring the 50th anniversary of Lincoln Center, it will present seven new ballets, five of them using decor designed by the distinguished architect Santiago Calatrava.

Santiago Calatrava's set for Benjamin Millepied's Why am I not where you are, one of the seven new works in New York City Ballet's "Architecture of Dance" festival

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The commissioned choreographers are Alexei Ratmansky (working to a score by Édouard Lalo, world premiere April 29); Benjamin Millepied (commissioned score by Thierry Escaich, April 29); Wayne McGregor (score by Thomas Adès, May 14); Christopher Wheeldon (score by Alberto Ginastera, originally commissioned by Lincoln Kirstein, May 29); Melissa Barak (commissioned score by Jay Greenberg, June 5); Mauro Bigonzetti (commissioned score by Bruno Moretti, June 10); and the City Ballet's ballet master in chief, Peter Martins (commissioned score by Esa-Pekka Salonen, June 22).

The season looks both forward, with these new works, and backward, with farewell performances for Yvonne Borree (June 6); Philip Neal (June 13); Albert Evans (June 20); and Darci Kistler (June 27, which marks the closing of the season). All the farewells are 3:00 Sunday matinees, so diehard fans can bring their children, urgently whispering to them as the curtain rises, "Remember this." Needless to say, the strategy probably won't work. (I took my then very young daughter to see Margot Fonteyn toward the end of her career; though already hooked on ballet, the child didn't recall the performance even the next day.) Nevertheless, adults often enjoy their effort to provide a youngster with material for future nostalgia. I did. And still do.

Well, the gala opening night program began not with dancing but with a video, explaining and illustrating the "Architecture of Dance" concept, which, truth to tell, feels more like branding than an artistic vision. Created by Kristin Sloan, a former City Ballet dancer, this canned introduction was a string of all too brief takes, moved along so speedily as to be almost beyond comprehension to anyone not reared on video games. It featured personable chat from Calatrava and Martins as well as other collaborators in the venture and footage of the dancers in rehearsal. It was succeeded by the live presence of Martins, standing before the golden bronze stage curtain to toast Calatrava and his wife, picked out by a spotlight from where they were seated in the First Ring. The gesture was rather dry; only the special three got to drink.

When the curtain finally rose to reveal Calatrava's stage design for the Millepied ballet, Why am I not where you are, it certainly let the air out of any balloons of anticipation. Calatrava is known not merely as an architect, but also as an engineer, a sculptor, and a painter. Although this is his first venture into design for dancing, he seemed to be just the right guy for the job. His freehand sketches, in what looks like an oily chalk, for the season's prospectus aptly suggest movement in space and, where the human body is concerned, if not originality at least the savvy taste to have chosen Rodin (who captured Isadora Duncan so effectively) as a mentor.

In the end what the Millepied ballet got was a huge, imposing structure very much in the style of Calatrava's striking buildings. It's a silvery double arch, one section brooding over the other. The two are joined by slender parallel rods, creating an environment that lends mystery to the dancers when they move behind it, becoming half hidden, though still certifiably visible. The inner arch hovers over empty space, which registers as a dusky cave through which dancers can enter the unblocked, brightly lighted part of the stage in which the more fevered action occurs.

Santiago Calatrava's set for Benjamin Millepied's Why am I not where you are, one of the seven new works in New York City Ballet's "Architecture of Dance" festival

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Millepied deals with the situation dutifully, but not imaginatively, though he says in a brief interview for the house program that the relationship between his choreography and the architect's structure was a collaboration between him and Calatrava. By the end of the one-small-page Q&A, the choreographer is telling a somewhat different story: "It's a large sculpture that sits on the stage, so I had to incorporate it into the choreography."

The choreography itself reflects the attempt by a number of younger classical-dance makers to overcome the sterility they find in today's ballets. They believe this arid state is the result of several decades' overemphasis of abstract dance. These choreographers rarely blame Balanchine directly--and it would be hard to sustain the argument that Concerto Barocco, The Four Temperaments, Agon, and Symphony in Three Movements are sterile. But today's classical choreographers do miss the presence of feeling that they think narrative and character brought to a dance. Since they reject "story ballets" from Petipa to Tudor as being, as it were, "so yesterday," they're trying to devise choreography that will touch the heart without reliance on plot. I would quibble with their logic, yet I've got to admire their effort to do something about the frustrating situation in which they find themselves.

Millepied's Why am I not where you are works by demonstrating feeling--something he's not naturally good at--in tiny passages, sometimes mere phrases, in between which he reverts to objective stuff. I thought his piece was specifically "about" something--a soulful man who stands outside the group that dominates his society (he's just not a frat boy, if you will), who succumbs to the temptation to give up his real self in order to join that group, and is thus doomed to disaster. In his case he loses the young woman destined to be his soul mate, though she never gives any indication that she is (she seems to be a typical sorority girl--one of the "In" crowd) before it's already too late. When I proposed this interpretation to a colleague, however, she looked at me doubtfully and said, "Really?"

The music for Why am I not where you are was commissioned from Thierry Escaich. French like Millepied, Escaich is the noted organist and composer in residence for the Orchestre National de Lyon. His score, The Lost Dancer, proposes shifting emotions--threat, excitement, fear, exhilaration, despair. It is full of possibilities.

In his Namouna, A Grand Divertissement, Alexei Ratmansky addresses the same issue Millepied tried to resolve, but then he usually does, and never seems to find it a problem. A significant part of this choreographer's profile is a love and respect for the old, so he often borrows from the devices of eras past, typically giving them a fresh life that makes them seem contemporary--that is, contemporary, but with marvelous ancestors.

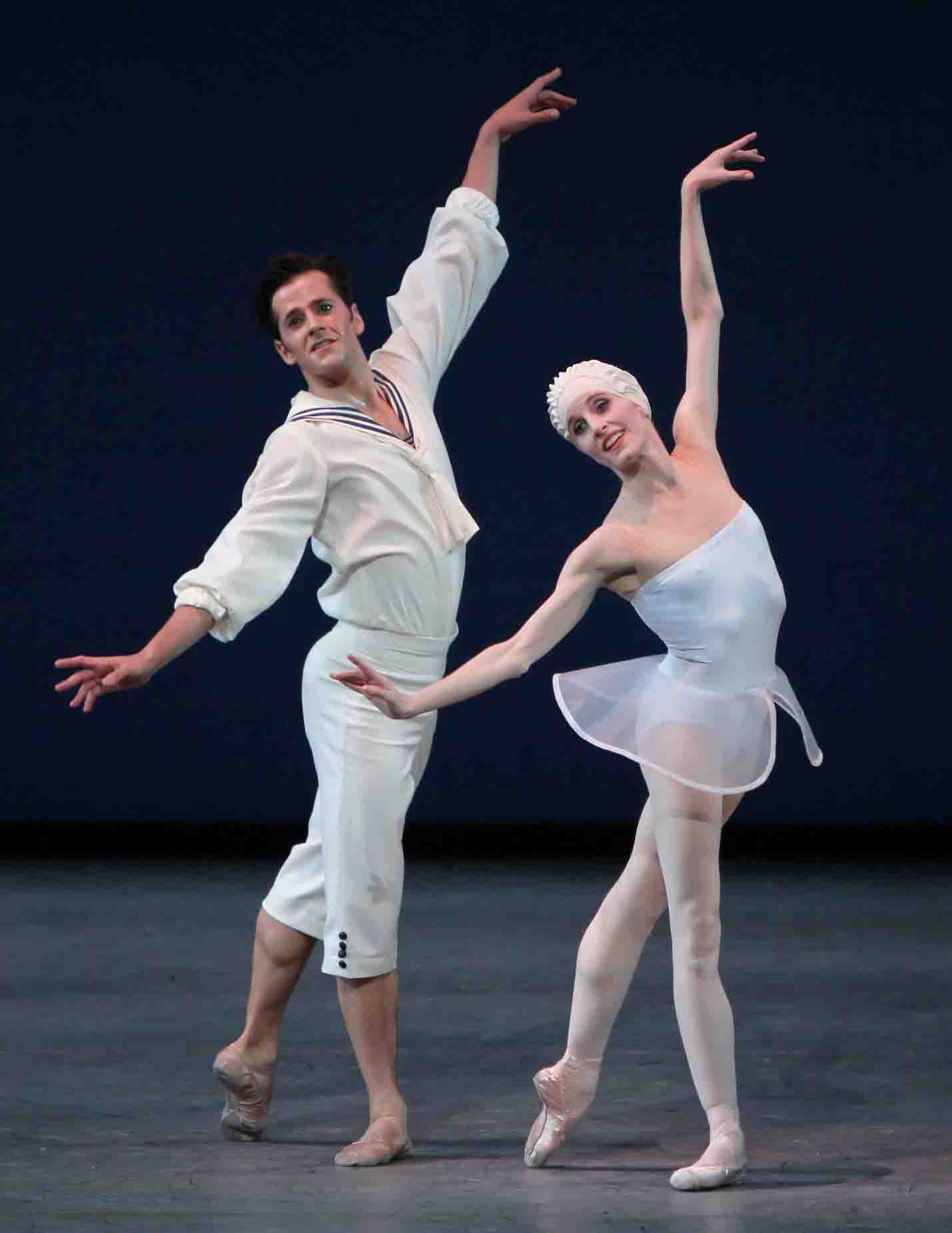

Wendy Whelan and Robert Fairchild in Alexei Ratmansky's Namouna, A Grand Divertissement, one of the seven new works in New York City Ballet's "Architecture of Dance" festival

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Namouna takes brilliant advantage of the riches of nineteenth-century ballet--the Russian school of that period, the French school, and the Danish school (that is, the Bournonville school), which reshaped the French principles and held on to many of them to this day. Ratmansky, who was trained at the Bolshoi Ballet's academy and returned to head the company for several years, to say nothing of doing a stint with the Royal Danish Ballet, evidently absorbed everything he was exposed to like a sponge. These delights--the mime, the dazzling details of the complex footwork, the major role assumed by the corps de ballet (sheer Petipa)--are all present and all transformed in Namouna.

An example of the transformation of the corps de ballet work, impressive enough in its old guise, with at least 16 dancers moving in unison in clear, simple geometric patterns, is enlivened for today by small, piquant deviations from unison activity without any loss of force. Complications of the patterns that enrich the original tactics are at once deliciously inventive and gently amusing. For instance, where the corps would shape up in straight lines, confronting the audience head-on, Ratmansky says to himself, Why not put the lines on the diagonal? Where you have a large number of gorgeous bodies costumed alike, why not vary the number of bodies in each line? Just about all his variations of this nature are clever and endearing--even to viewers who know little to nothing about the original conventions.

Ratmansky's music for this ballet is Édouard Lalo's Namouna, made for a 19th-century French ballet. His "scenic investiture" is, unlike Calatrava's attention-riveting constructions, no more than a backdrop that accepts the projection of light in colors that vary with the mood of the moment. The dance is unconscionably long, yet never repetitious or boring. Its stars are Wendy Whelan, Robert Fairchild, Jenifer Ringer, and Sara Mearns.

Sara Mearns in Alexei Ratmansky's Namouna, A Grand Divertissement, one of the seven new works in New York City Ballet's "Architecture of Dance" festival

Photo: Paul Kolnik

These comments on the first two new ballets in the "Architecture of Dance" season are just a first impression, formed in the hectic gala atmosphere engendered by the patrons in the prime seats, who make generous contributions to the company's coffers and for whom opening night is as much a social occasion as a theatrical one. I'll have more to say after a second, calmer look when each work is given its first showing to the general public--the Ratmansky on May 5, the Millepied on May 22.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

1.2.3 Festival / Joyce Theater, NYC / April 13 - 25, 2010

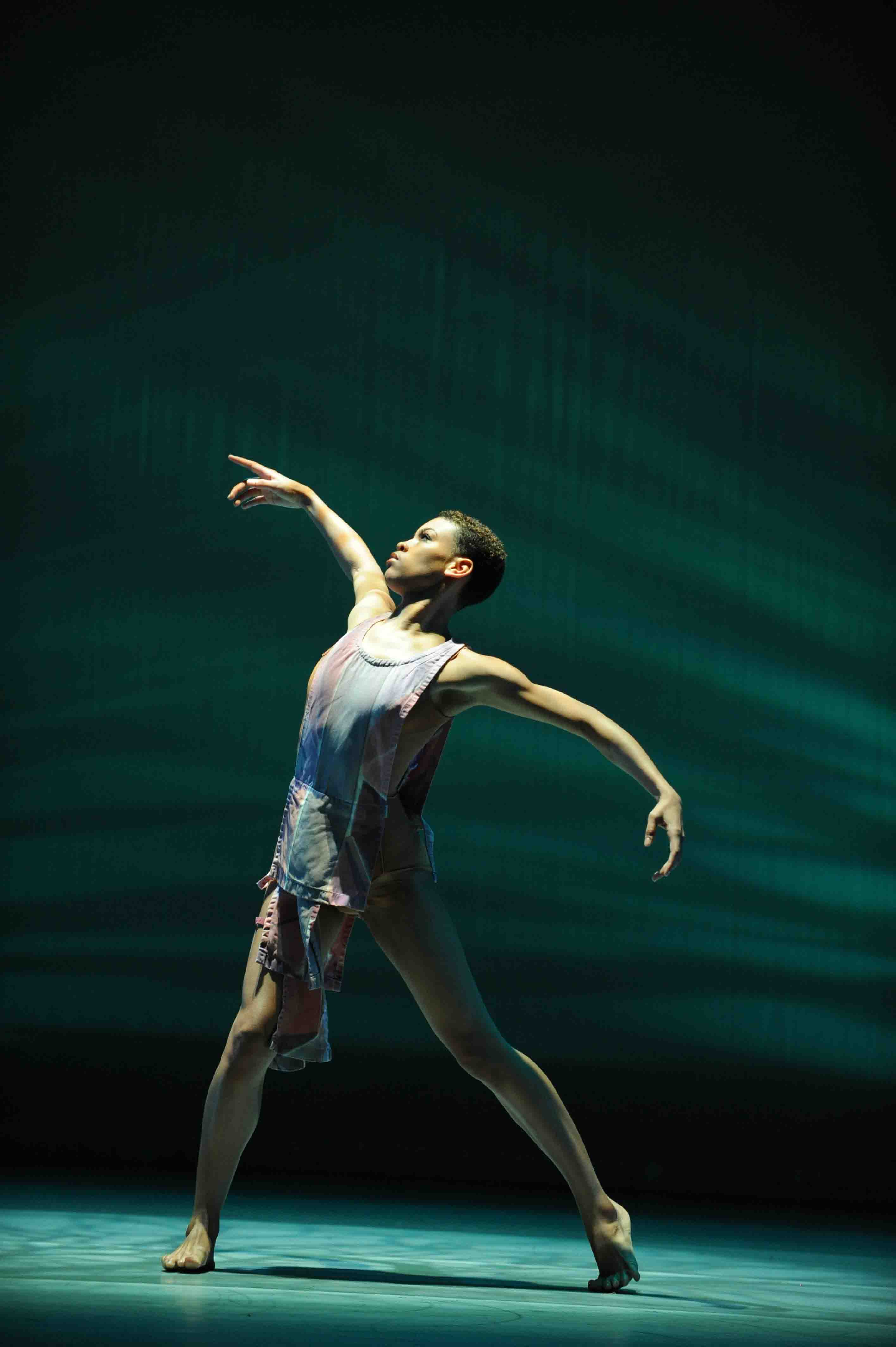

Ailey II's Ghrai DeVore in Judith Jamison's Divining

Photo: Eduardo Patino

Opening night of the 1.2.3 Festival at the Joyce was the tasting menu. The three (count 'em) companies involved in this yearly event--ABT II, AILEY II, and Taylor 2--contributed one substantial, and revealing, dance to the program. Each little troupe is an offshoot of a top-notch, grand-scale company: American Ballet Theatre, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and the Paul Taylor Dance Company. The junior groups serve as ambassadors of dance, touring to venues that lack the space, budget, and sizable audience needed to host the grander companies, all the while increasing their professional aplomb. The young members of the second companies are, for the most part, on their way to the big time, and the evening at the Joyce displayed both the style that distinguishes the parent company of each and the dancers' individual gifts.

Taylor 2 opened the program and won the day with its rendition of Company B, engagingly set to bubbly or yearning songs popular in the Forties, sung by the Andrews Sisters. Taylor's choreography shadows the moods of the music with images of World War II, in which many a lighthearted boyfriend or cut-up suddenly found himself an armed soldier facing the enemy and, often, death.

In this way, "There Will Never Be Another You" becomes not just an ex-sweetheart's lament over a romance that has gone awry, from which both parties are likely to recover eventually, but rather for a romance cut off in one fell swoop by a visit to the young man's parents from a pair of somber emissaries of the United States Armed Forces.

Similarly, Taylor gives an extra dimension to the lyrics of "I Can Dream, Can't I?" by having a young woman's wistful query about the unresponsive object of her affections answered by images in silhouette of two fellows who only have eyes for each other. Elsewhere, in "Pennsylvania Polka" and "Oh Johnny, Oh Johnny, Oh!," the impulse is chiefly one of ebullient cavorting, something, it seems nowadays, that America will never retrieve.

The Taylor 2 dancers embodied the unfettered feelings of youth required for Company B, yet their skills and assurance are utterly professional. The combination is irresistible. Two of the three men in the company are, understandably, throwbacks to the beefy types Taylor often commandeers for his main company; this may be part of the "blast at ballet" that choreographers of his generation needed to make as they carved their own, idiosyncratic, path.

As a group, the guys are irrepressible; the sun seems to shine on their innocent rowdiness. The three women are very individual and capable, bless them, of conveying mood and emotion through dancing rather than add-on histrionics. Latra Wilson was my favorite--juicy and teasing in "Rum and Coca-Cola" as a Trinidad native exhibiting her charms to a trio of American soldiers who lie lazily on the ground, ogling the object of their generic desires. She is, deliciously, "working for the Yankee dollar," and she's worth a million.

ABT II's contribution to the program was the evening's weakest entry, but this was not primarily the dancers' fault. The choreography of Edwaard Liang's Ballo per Sei defeats them, being both physically illogical (hardly a step in it segues into a move that the body would instinctively do next) and unmusical (an untenable response to its Vivaldi score). What's more (or, rather, less), for long stretches the piece is intolerably boring. ABT II has, for some time now, prided itself on commissioning new works to be made on its dancers, who would then be part of the "creative" endeavor, as if dancing itself were not creative. I've felt all along that an emphasis on performing the classics might serve them better.

Still, Liang's choreography wasn't entirely to blame for the not-so-hot performance of the dancers. The current company members are nowhere near such able practitioners of their trade as, for instance, the members of Taylor 2. Comparing them, more aptly, to a classical group, their technique lacks the sharp edge and brilliant footwork on view at the annual performances given by the School of American Ballet, which grooms dancers for the New York City Ballet.

ABT II's Brittany DeGrofft and Brian Waldrep in Edwaard Liang's Ballo per Sei

Photo: Rosalie O'Connor

The young women of ABT II are more capable technically than the men who, moreover, do not always make reliable partners. And yet all the performers gave the audience glimpses of talent that just needs time and guidance to mature. The one passage of fully fledged dancing came from Brittany DeGrofft in the long adagio duet at the heart of Liang's piece. DeGrofft had evidently convinced herself that her role was expressive, and expressive she was in her rendition. Her performance wasn't profound--she's probably too young in experience for that--but she obviously knew what it should be like. In time, with better material, she may be wonderful.

The denizens of Judith Jamison's Divining, presented by Ailey II, seem to be an ancient nomadic tribe given to mystical rituals. A small group of them that opens the piece and an expanded one that appears at the end move together, suggesting a powerful collective consciousness. For the all-important middle section of the dance, these strong-bodied, strong-minded people conjure up a female goddess--to protect them and lead them, it would seem; perhaps to inspire them. Danced by the remarkable Ghrai DeVore, this central figure is one you're not likely to forget.

DeVore rivets your eyes the moment she sets a foot, delicate but sure, on the stage. Just physically, she's stunning. Her arms have the fragile beauty of a slender pre-adolescent child's; her thighs are those of a mature athletic woman, full and vigorous. Her head, exquisitely shaped, is perfectly poised; her neck might be its pedestal. Large eyes, emphasized by ebony makeup. A luscious mouth. The cut of her black hair must have been designed by a sculptor: close-cropped but thick from crown to earlobes, then shaved away below. Granted, beauty is as beauty does, but here it does fantastically.

In action, DeVore is vehemently expressive, yet subtle in detail. She can shift, with no visible transitions, from tiny vibrations to steady extended balances, from staccato thrusts to soaring leaps. At one point she jackknifes over, one palm slapping the floor, while the opposite leg reaches straight skyward, the foot seeming to pierce the atmosphere like a fatal arrow. For DeVore, an action like this is not a feat; it's business as usual. No, she's not on her way to stardom. She is already a star.

Subsequent performances in the 123 Festival will be devoted to full programs by a single one of the three participating companies. Taylor 2 is offering the most captivating show--Aureole, 3 Epitaphs, Company B, and Esplanade--four masterworks by the choreographer in which joy or fun has the upper hand, not one of them suggesting, as a good part of Taylor's complete repertory does, that life is nothing but an amalgam of evil, madness, violence, and despair. (Think of Last Look). What better way to lure prospective fans than the combination of excellence and pleasure?

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Trisha Brown Dance Company / Baryshnikov Arts Center, NYC / April 7 -11, 2010

Leah Morrison and Nicholas Strafaccia in Trisha Brown's Opal Loop/Cloud Installation #72503

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Trisha Brown, celebrating the 40th anniversary of her company at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, is a certified original and quite likely a genius. More often than not, her choreography has been conceptual --from the early iconoclastic task dances executed in silence to lush operatic productions. This trait makes her very popular with European audiences, who dote on ideas, and with American viewers of an intellectual bent. Not that her work has ever seemed arid or calculating; as much as it's governed by structure, it is tempered by Brown's wry wit.

As her career evolved, Brown enriched her dances through collaborations with visual artists (notably Robert Rauschenberg) for stunning costumes and environments and through music that ranged from jazz to the classics. Not least, she has always been uncannily alert to the sensuousness of flesh in motion.

She was a gorgeous dancer herself, one who gave new depth of meaning to the word fluidity. She executed the deceptively casual movement she designed as if her body were a silk scarf being drawn through a keyhole. Yet, paused even for a nano-second, she had a firm rooted look and a sense of center so profound, it could never go awry. What's more, she convinced you that what she was doing was practical, logical--quite simple, really. Even at their best, her marvelous dancers couldn't outdo her, though they worked sensitively and diligently in her mode, the veterans duly passing the word along to the rising generation.

Brown's face was remarkable too: as craggy as that of an early New England settler steadfastly enduring the physical and emotional hardships inherent in claiming a new world or perhaps that of a pioneer, dauntlessly pushing the American horizon westward. (Actually, Brown was a native of the Pacific Northwest, which has produced a remarkable number of dance innovators, among them Merce Cunningham, Robert Joffrey, Mark Morris.)

Perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of Brown's body, however, was her back, which she bared and turned to the audience in the 1994 If you couldn't see me. (Throughout this10-minute solo, the dancer faces upstage.) The spine and its attendant muscles riveted our attention. The title of the piece is evidence of Brown's ever-amused and amusing irony. Actually, she couldn't see us. We could see "her" as we gazed at that eloquent back; we just couldn't see her face. This dance was (and remains), subtly, as radical a challenge to the accepted conventions of dancing as Brown's blatantly idiosyncratic early work that had her company signaling on rooftops or walking on walls.

Brown is 73 now and no longer performs If you couldn't see me--or indeed any of her dances--for the public. The loss is immense, though inevitable. At BAC, the solo was done at alternating performances by Leah Morrison and Dai Jian. I saw both.

Morrison, a lovely looking young woman, recalls Brown in her long limbs, cushioned joints, and velvety way of insinuating her movement into space, though she lacks Brown's complementary staunch quality. Wearing the simple white costume Rauschenberg designed for Brown--the leotard-style top deeply scooped to leave the back naked, the calf-length skirt slit at both sides to free the legs--Morrison makes aspects of the choreography scrupulously clear: the occasional angular moves of the arms, for instance, that offset the impression of unfettered flow. Throughout the piece, her plainspoken rendition, free of attitude and adornment, is a blessing. But, when it comes to the essential, her back isn't compelling.

The ability to project through the back while deprived of the drama of the face is a rare gift. Apparently Morrison wasn't born with it; I don't know if it can be learned. The other element that Morrison lacks can be acquired. Brown was in her late fifties when she choreographed If you couldn't see me; her back had the topography of a seasoned athlete's--vertebrae, muscles, and tendons distinct to the naked eye. That gnarled-tree effect, suggesting the wisdom of visceral experience, was an enthralling sight.

It's only fair to note here that Morrison won a 2008 Bessie award for her performance of this role, so my reservations about her rendition may make me a dissenting party of one.

Jian is new to the role and still has a long way to go. He's an undeniably adept dancer and a typical Brown acolyte in his softness and fluency. His dancing adds a fascinating element to the choreography because, since he was born and trained in China, Asian dance influences his way of moving--just slightly, like the merest trace of a "foreign" accent. At one fleeting moment he looked like a statue of an Eastern god, poised in the shelter of his temple.

Like Morrison's, Jian's back is relatively inexpressive, but in his case the radical concept of a dancer's offering the audience the back rather than the face is undermined by the fact that, though Jian wears the split skirt, his entire torso is left nude. Think of it this way: In traditional Japanese costume, the erotic effect of exposing the nape of a woman's neck depends on the elaborate swathing of the rest of the body. To bare shoulder or bosom as well would kill the original intention.

The 1994 If you couldn't see me was the first solo dance Brown had made in 15 years. In 1995, she converted it into a duet called You can see us, which she performed first with Bill T. Jones, then, a year later, with the ballet superstar Mikhail Baryshnikov, as a pièce d'occasion. I saw the latter casting. The two moved side by side, she facing upstage, as was her wont, he down, as was his. Unlike the original solo, which engenders piercing observations and haunting questions in its viewers, the duet was no more than a curiosity.

Created in 1980, Opal Loop/Cloud Installation #72505 remains one of the most beautiful dances I've ever seen. The BAC audience seemed to be seduced by it too.

A black curtain veiling the farthermost area of the stage pulls apart to reveal the quartet that comprises the full cast. The four stand quietly, in profile, enveloped in a fog. Released by the opening of the curtain, the mist pours out to fill the entire stage and drift tentatively towards the spectators. In the course of fifteen minutes, as the mist swirls, assuming ever-changing shapes and degrees of density, the performers, too, move out into the space, becoming clearly visible, nearly invisible, and all the shadings in between.

The moving figures do what Trisha Brown's people usually do, which sometimes looks like dancing, at other moments like skeins of the pedestrian gestures made by ordinary people getting on with their lives while absorbed in some sort of inner mediation. The danciest passage puts a male-female pair at the center of an imaginary diagonal line, partnering and not quite partnering, while the remaining man and the remaining woman position themselves at either end of that unseen line, each going through the movements the duet has assigned to his or her gender.

The mist, which moves gently, like a colony of scudding clouds changing shape in a gentle breeze, has been created by Fujiko Nakaya and is, rightly, referred to as sculpture. The crucial quality of this art, though--which, the house program instructs us, is intended to evoke the climate of Brown's Pacific Northwest birthplace--is that it's evanescent. Even more so than dancing, but in the same way. Its poignant beauty is intensified by the fact that it doesn't last.

Opal Loop has no sound accompaniment beyond the hiss of the water being transmuted into clouds, the dancers' padded footfalls, and, occasionally, their breathing because, for all the languorous mood it evokes--the feeling of swaying in a hammock, perhaps, as a summer day fades from sunset to twilight--the movement can be swift and demanding.

Opal Loop leaves its viewers with many potent afterimages--and afterthoughts as well. It encourages you to treasure the ordinary and shows you how the casual becomes important, even monumental.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary