Seeing Things: January 2010 Archives

New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / November 24, 2009 - February 28, 2010

This story has a back story. Let me whisk you through it.

Some two years before the New York City Ballet danced the January 21st world premiere of Alexey Miroshnichenko's The Lady with the Little Dog, negotiations had broken down between Peter Martins, who directs the company, and Alexei Ratmansky, then head of the Bolshoi Ballet in his native Russia. They'd been discussing the possibility of Ratmansky's becoming the City Ballet's Resident Choreographer. (The job had been created a decade ago for Christopher Wheeldon, who, having formed his own small, ambitious company in 2007, subsequently wanted to give it his full attention.) Shortly after Ratmansky's negotiations with City Ballet collapsed, he was snapped up by American Ballet Theatre.

Ratmansky was obviously a catch--he and Wheeldon are widely considered to be by far the most gifted choreographers in classical dance today--and balletomanes entertained the foolish hope that he would prove to be "another Balanchine." Of course he wasn't, but observers were consoled by his abundant gifts: a dance vocabulary that is inventive yet firmly rooted in traditional classical technique; the wit and human warmth of his creations; his respect for (and delight in) the past and his ability to make it new.

When City Ballet announced that this season would see a new ballet commissioned from another Russian, Alexey Miroshnichenko, hopes were more modest, but still unrealistic--that Miroshnichenko would at least prove to be "another Ratmansky." No such luck.

Sterling Hyltin and Andrew Veyette in Alexey Miroshnichenko's The Lady with the Little Dog

Photo © Paul Kolnik

The Lady with the Little Dog is, at best, a sweet Valentine of a ballet--pretty and charming, but without much significance. It was inspired by Chekhov's poignant, similarly titled story in which a man and a woman, each leaving a disappointing spouse behind, visit a seaside resort, ripe, for different reasons, for a passing affair. He's an aging playboy; she's a delicate young thing who craves more from life than a marriage that starves her imagination. Instead they find a fierce attachment (call it love) they can't escape.

Miroshnichenko adopts the names Chekhov used for his main characters, Anna Sergeevna and Dmitri Dmitrievitch, but keeps the proceedings semi-abstract. Sterling Hyltin as Anna has the youth and delicate beauty of the young woman's Chekhovian ancestor, but Andrew Veyette, as Dmitri, is merely a generic attractive young man, as caring and tender as a romantic heroine might wish and a swell dancer to boot.

Boy meets girl when Anna is out walking her fluffy little dog. They are attended by a male octet in short-sleeved gray unitards. The house program calls them Angels, but their movements are often those of adorable puppies. The cuteness factor is not as unbearable as you'd think, but it--and the central part these fellows play in guiding the couple's encounters, even to simulated nudity and intercourse--is enough to remove the ballet decisively from the Chekhovian realm of small truths that, accumulating quietly and inexorably, end by piercing the heart.

The most disheartening part of Miroshnichenko's effort, though, is its lack of interest and invention sheerly as dance. To be sure there are two big pas de deux--obvious choreographic challenges--but the results are invariably banal. In the falling-in-love duet Veyette lifts and turns Hyltin so that her legs swirl out into space, in the familiar way of ice-dancing couples, This "floating on air" is a metaphor for love's ecstasy, but it has become a cliché and Miroshnichenko's bag of tricks is far too full of them.

The score, by the Russian composer Rodion Shchedrin (the husband of the celebrated ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, to whom the ballet is dedicated), couldn't suit the piece better, being as delicate and sweet as a meringue and equally devoid of substance. Philipp Dontsov's scenery is spare, essentially a gauzy front cloth that lifts up and a backdrop that stays put, both broken by pale rectangles, as if to indicate modernity. For variety's sake, the upstage drop is subjected to mood lighting by the City Ballet's Mark Stanley. One can justly accuse Stanley of making most ballets too dim, but he is not often given to the trite ploy of using rhubarb red to indicate erotic passion.

To my mind, the only worthy aspect of The Lady with the Little Dog is its serving as a vehicle for Hyltin, extending her beyond her crisp technique to create a character who is well-nigh irresistible. As I knew you'd want to know, the pale, fleecy scrap of a live lap dog that she walks at the ballet's opening is the dancer's very own, and the vibes between them are indeed delectable.

Dancers of the New York City Ballet in Peter Martins's Naïve and Sentimental Music

Photo © Paul Kolnik

Peter Martins's latest ballet, Naïve and Sentimental Music, to the John Adams score from which it takes its name, had its premiere on November 24, 2009, for the gala opening of the City Ballet's season. And it was likely that the choreographer had the grand gesture in mind when he cast nearly all of the company's principal dancers in it. Of the cast's 26 performers, only one, Adrian Danchig-Waring, was still "just" a soloist, but he's clearly headed for the top category and entirely deserving of it.

Unhappily, the grand gesture did little to make Martins's ballet memorable. Yes, it was impeccably performed, yet the choreography adamantly refused to reveal the individual distinctiveness that had made each member of this top-of-the-crop group worthy of the ranking. For Martins, it seemed, the strong, clear technique that almost all of them displayed was sufficient in itself. Is he immune to the love that can be inspired by the particular dancing temperament of an individual artist?

For the record: The piece comprises three sections. The first is the most highly populated, with seven couples elaborating, in different groupings, on Yvonne Borree's opening statement of unfurling a leg now to the front, now to the back. The simple movement develops into many a speedy challenge until the stage looks charged with activity. The women--in beautiful tunics by Liliana Casabal that range through a spectrum of blues and greens--are as light and sharp-edged as a Kleenex; the men, naturally beefier, put more obvious energy into their steps. All of them perform as if "exactitude" were their mantra. But the point of their activity is either invisible or, more likely, non-existent.

The second section is devoted to adagio dancing, with its cast of three couples in pure white taking turns at being in the spotlight while the two remaining pairs do complementary slow duets at a distance in a meditative twilight. It is, as might have been expected, the women who stand out: the luscious Sara Means; Maria Kowroski, the diva of pulled-taffy dancing; and the about-to-retire Darci Kistler, who happens to be the choreographer's wife.

As was also to be expected, the movement is abstract. And then suddenly in the final duet--for Kistler, with Stephen Hanna--the couple is interrupted by a black-clad man who steals Kistler away from her partner and proceeds to conduct her through a rendezvous with death reminiscent of, yet nowhere as powerful as, the macabre and sensuous one in Balanchine's La Valse. Next, unfathomably, the man in black is replaced (not thwarted, simply replaced) by Hanna, and the dance returns to the ineffable rites of a gated (think heavenly) community. Are we to understand, from that brief narrative intrusion, that Kistler is undergoing a near-death experience (perhaps her retirement)? The problem here is that Martins has failed to make his intentions clear.

The third movement, also for three couples, the women costumed in gorgeous shades of red, has the kind of ferocity you'd expect if someone had yelled "Fire!" in a crowd. In response to the music, the movement now blazes, though it is always tamped down a little by Martins's insistence on a seamless flow in the action.

To close the piece, the entire cast assembles for a geometrically ordered finale that has absolutely no dance fervor in it. I saw the ballet twice, and each time, as the curtain came down, I felt I hadn't witnessed anything significant--or even simply entertaining.

After their respective premieres, the Martins and Miroshnichenko ballets appeared on the same program for the City Ballet's annual New Combinations evening, which is meant to honor Balanchine's birthday. Surely, in his lifetime, Mr. B knew one should be wary of choreographers bringing gifts.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Noche Flamenca / Lucille Lortel Theatre, NYC / December 24, 2009 - January 16, 2010

What better way to spend New Year's Eve than watching Noche Flamenca?

The Lucille Lortel Theatre, intimate in size, is dark and gloomy, the seats for the onlookers sheathed in a deep red velvet that hints at half-hidden passions. It's not as atmospherically decrepit as the East Village's Theater 80, where the troupe usually gives its extended summer seasons, but it will do.

Besides the change of venue, there's been a change in billing: The name of the company's diva, Soledad Barrio, one of the most thrilling dancers in the world, now towers over the name of the company. With good reason.

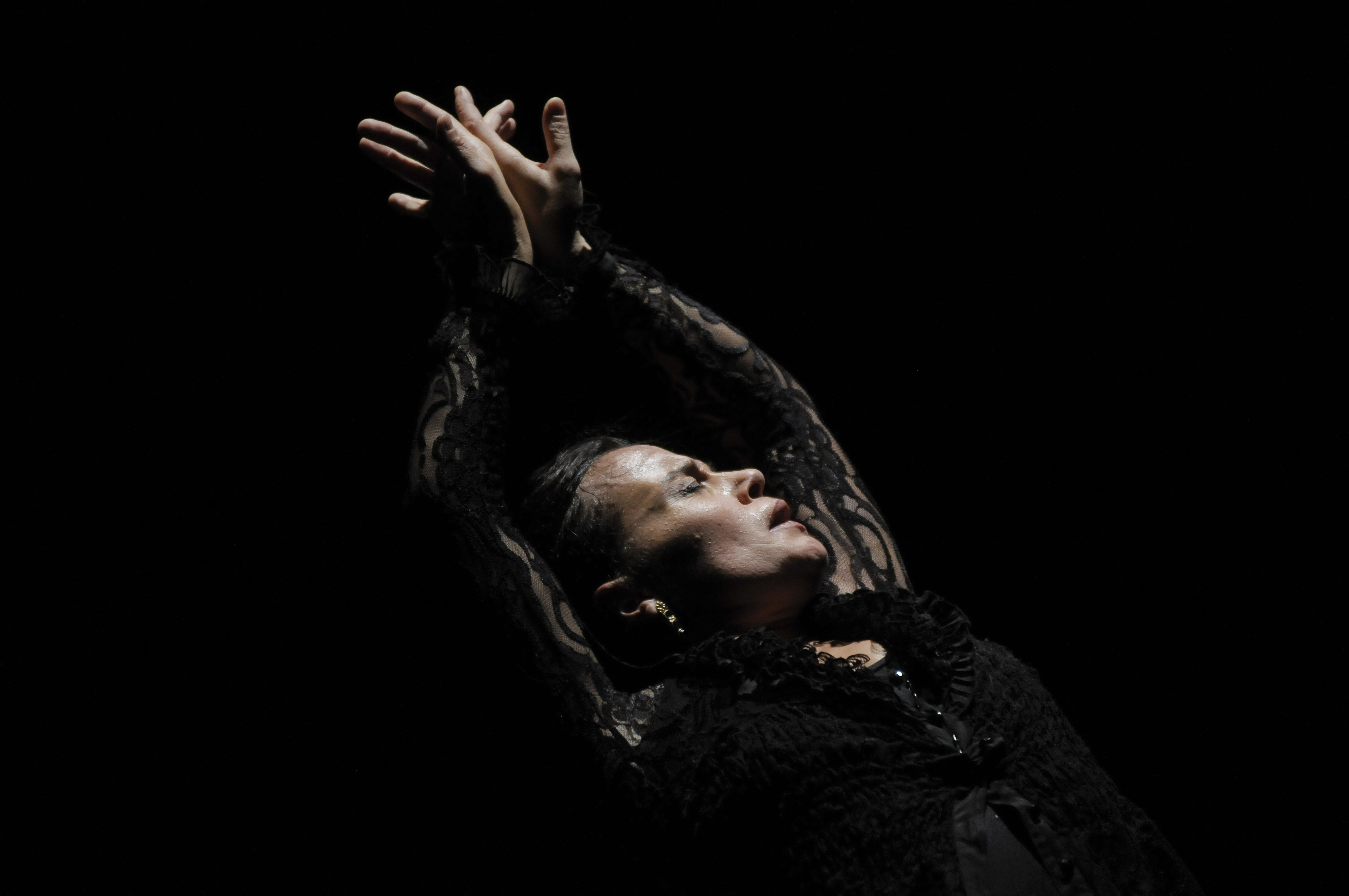

Soledad Barrio

Photo: Telam

Barrio is simply more intent than even the most acute dancers. Onstage, she becomes a person who takes everything seriously and personally, beginning with the assumption that life is tragic.

In a solo that climaxed the program, Barrio appeared as a contender with deep, dark forces. Fabulously costumed for the encounter, she wore a black ankle-length dress with long lace sleeves and a lace back that wove a spidery pattern over her flesh. Its artfully layered skirt, glimmering with streaks of jet beading, promised to do its own dancing if provoked by the slightest movement of her hips.

After her entrance, though, Barrio stood perfectly still for a very long time with her back to the public--a feat with which few dancers can command their audience's attention. Her spine was arched, her head placed to present a stern profile. Then, a swift turn, and she faced her watchers directly, her gaze defying its communal gaze at her. She raised one arm, paused, then the other, paused, and finally added a baroque flourish of her fingers. Behind her, singers and instrumentalists waited, as if they were comrades--soul mates, perhaps--with whom she would undertake a perilous journey.

Head swiveling, she stomped halfway across the stage, and a rose that had ornamented her hair dropped to the dingy floor. She saw it fall, gazed at it, as if to acknowledge and pity its fate, and left it where it lay. It was a live rose, I believe, and its loss an accident.

Lifting her skirt to reveal her pale, powerful legs, she used them like pistons, whipping herself into a frenzy of high-voltage footwork. Halting abruptly, she covered her face with both hands for a moment, as if shielding her eyes from an unbearable sight, then emerged from that screen even more fully possessed by her dancing. Her actions no longer seemed to be a performance but rather the work of some primal force of nature being given free rein as we, her observers, ceased to exist for her.

She passed her forearms across her face, then, driving her heels into the floor, raised her arms high over her head, twisting her hands and fingers, transforming them into exotic flowers. She stopped, looked down once more at the maimed rose, then calmly joined the little single-file line formed by the musicians walking offstage, as if to their next pilgrimage.

In the production I saw at the Lortel, Barrio was the only female dancer in the little troupe. Well, what woman could hold a candle to her? In modern dance, Isadora Duncan and Martha Graham. In ballet, maybe Nora Kaye, in her Tudor roles. Certainly no one we can go and see today has Barrio's transformative power.

Soledad Barrio, in the black dress

Photo: Andres D-Elia

The men of the current troupe naturally serve as foils to its star, yet they are extremely accomplished and shown to good advantage. Antonio Jiménez offers an intriguing combination of sturdy legs, scintillating footwork, and delicate gestures of the hands. In his solo, he often hugged his arms tight to his chest, his hands clutching the flaps of his open jacket, like an infant holding on for dear life to its security blanket. And, while he danced, he'd frequently close his eyes, as if to keep his fierce energy within his control. Yet when his solo wound down, he just walked off, matter-of-factly, like an ordinary pedestrian, toward a red light that gleamed in the wings, a fiery sun.

Juan Orgalla opened his solo with a fusillade of footwork. It seemed as if a single step of his boot could kill. His spectators might well have thought, "If he has a heart, you'd never know it; he's all about power and command, about a way of being masculine that's native to flamenco and the culture it stems from." Many a woman has been (and perhaps still is) delighted to submit to the type Orgalla conjures up. A feisty female would laugh him away; a timid innocent would be terrified by the mere idea of being alone in a room with him. Still, when Orgalla segued into a long passage of gentler, more subtle footwork, it became clear that he's not merely a mirror of dominating masculinity but, rather, a canny virtuoso.

Martin Santangelo, the company's founder and director (and, incidentally, Barrio's husband), choreographed the program's two group pieces--Alba (about a band of American heroes in the Spanish Civil War) and Refugiados (inspired by the writings of refugee children in dire circumstances). In the latter, Santangelo's manipulation of dancers, singers, and instrumentalists in the space is a small architectural tour de force. Still, there's no denying the fact that flamenco, when it's truest to its nature, prefers the solo or, at most, duet form. It is non-narrative and shorn even of a particular theme other than the one that lies at its heart--life's proud face-off with death. Flamenco is also essentially improvised and so resists the services of a choreographer. I understood that the solos I watched as the clock inexorably ticked its way toward midnight might look very different in 2010. ¡Feliz Año Nuevo!

Soledad Barrio with musicians of Noche Flamenca

Photo: James Morgan

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater / City Center, NYC / December 2, 2009 - January 3, 2010

Judith Jamison, Artistic Director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Photo: Andrew Eccles

Beginning with the opening night gala, I visited the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater ("The Ailey," to its friends) many times during its month-long City Center season, which celebrated Judith Jamison's 20-year tenure as artistic director. Jamison will become "artistic director emerita" at the end of this year. Her successor has not yet been named, but it will be hard to find her equal--first as a star dancer, then as a leader with unassailable authority, a sharp eye for talent, a tough work ethic, and irresistible charisma.

Opening night felt relatively subdued compared to the high-voltage atmosphere generated by such occasions in recent years. Its first half was devoted to generic speeches, excerpts from Jamison's own so-so choreography, and a pièce d'occasion made in her honor by Robert Battle.

Battle's offering, a male duet titled Anew, may have been about succession. If so, too subtly so. Its only striking element was the poised control, cloaking ferocious energy, of Jamar Roberts and Clifton Brown as they prowled through their space like big cats in the wild. Traditionally, this has been a skill of just about every member of the company, male and female, black and white. Jamison has brought it to a full flowering, as she has the leaps that shoot across uncanny stretches of space; and the sky-high leg extensions from a daringly tilted body. Performance after performance, Jamison's dancers claim the right to be called acrobats of God.

Excitement quickened in the second half of the program, thanks to a knock-out performance of Ailey's own signature piece, the 1960 Revelations. One of its highlights was Amos J. Machanic, Jr.'s exquisite and original rendering of "I Wanna Be Ready," that gut-cruncher of a solo in which the sheer physical challenge (made, of course, to look effortless, even delicate) comes across as a humble, poignant cry of faith. More thrilling yet was the familiar, though never twice the same, sight of Linda Celeste Sims and Glenn Allen Sims performing the "Fix Me, Jesus" duet, which they've evolved to the point of incandescence. She lets herself fall from a succession of precarious positions, trusting he'll there to save her from self-destruction, and he is, but these and many another feat--of coordination, of balance--have become as refined as a silkworm's threads.

Overall, the company's technique seems to be suddenly stronger and clearer than I've ever seen it. Often when this occurs in a dance troupe, the technical "improvement" is accompanied by the sacrifice of the dancers' individuality, the texture of their movement, and that invisible but essential quality of soul. (Today's New York City Ballet is a significant example.) The Ailey, on the other hand, seems to have increased its physical exactitude in order to make the choreographers' (and dancers') visions more piercing.

Repertory remains the Ailey's perennial problem. This was clear from the Best of 20 Years anthology, which presented excerpts from pieces Jamison commissioned, revived (Alvin Ailey's included), or acquired during her two decades as artistic director. The deficiency surfaced again in two of the three works given their premieres this season. If you can look behind the stunning performances the dancers invariably give it, the choreography offered by the Ailey is, with few exceptions, thin in invention, and stymied by prefabricated emotional agendas.

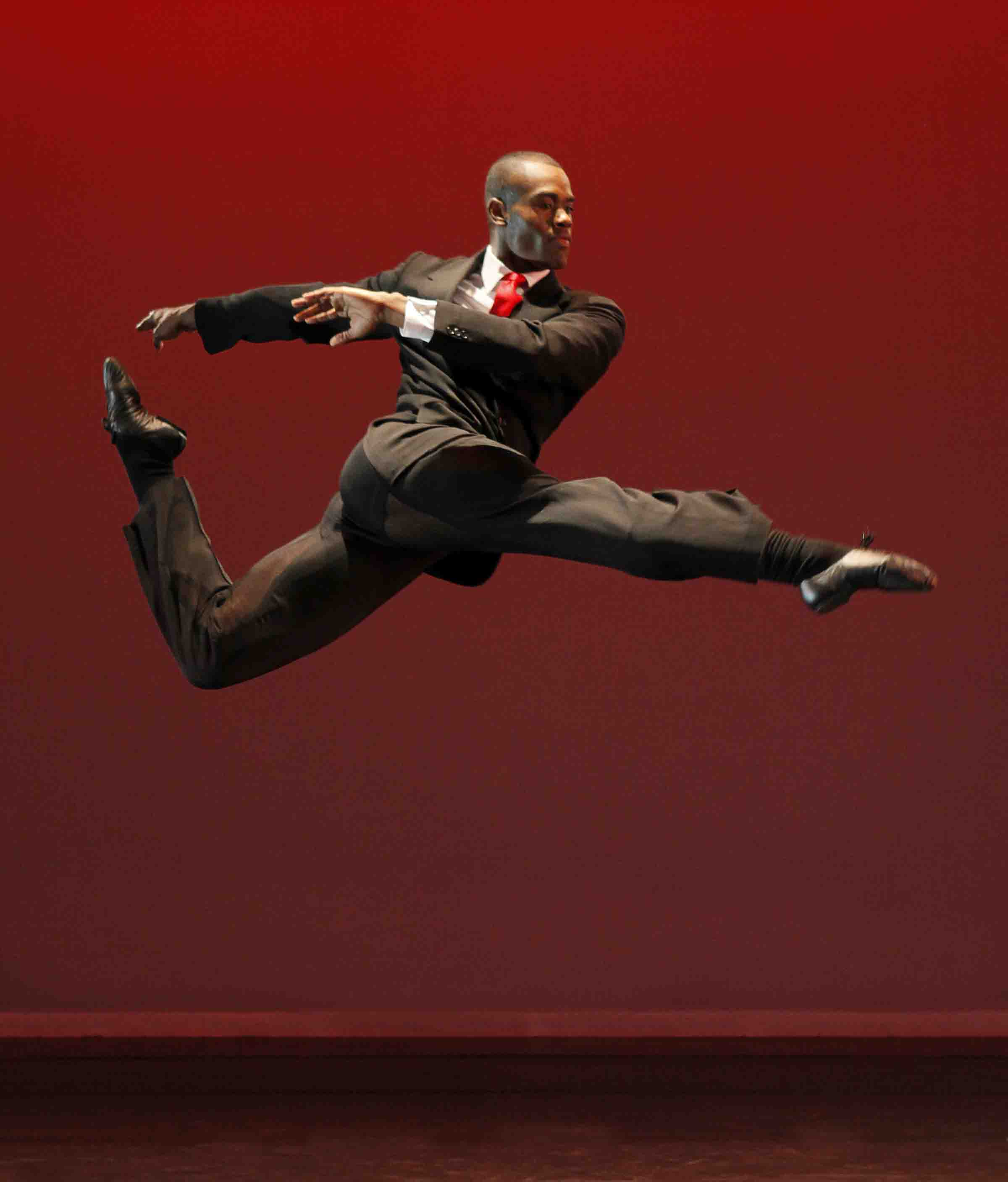

Jamar Roberts in Judith Jamison's Among Us

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Jamison's own Among Us (Private Spaces: Public Places), to music by Eric Lewis, shows us the fantasies of people at an (art) exhibition, the art naïf pictures being by Jamison. Granted, the encounters do include the traditional museum pick-up, but half of them remained inexplicable to me, even on a second viewing. The imaginary shenanigans are encouraged by a genie, played by Clifton Brown, a dancer so beautiful and gifted he can even get away with a tall blue feather waving from the top of his skull.

Linda Celeste in Judith Jamison's Among Us

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The movement vocabulary draws from ballet, jazz, Horton via Ailey, and middle-eastern genres; despite this generous pluralism, the choreography falls flat. The most compelling dancing in the show comes from Linda Celeste Sims, all filigreed whirling in a ravishing flamingo-hued dress with a lushly flared skirt, and Hope Boykin, somberly expressive, in a deep purple business suit with an ingeniously pleated vent in its skirt that allows and draws the eye to her full-bodied movement. As I've indicated, the costumes, by Paul Tazewell, are marvelous, but clothes alone don't make a viable dance.

Uptown, by Matthew Rushing, one of the company's senior and most revered dancers, attempts to chronicle the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, in which a confluence of African-Americans made achievements in the arts (Langston Hughes, Josephine Baker) and social concerns (W.E.B Du Bois) that would influence generations to come. Both the street life and partying life of the period were memorably sassy too. Perhaps inevitably, the subject required as much talking as dancing--so the piece has a narrator (the hyper-fueled Abdur-Rahim Jackson at the performance I saw), who both speaks and moves, and recordings of the greats. Not unexpectedly, the choreography often falls prey to the impossible task of miming what is spoken. Overall, the result is more like an educational documentary film than a real live dance. By next season it might be playing to kids in middle school.

Nevertheless, Uptown contains occasional passages--the "Weary Blues" section, for instance--that suggest Rushing has some flair for choreography. So I hope he'll be given another chance--perhaps in a workshop situation, to lessen the pressures of a big, important, and expensive production--to create a work that isn't so dependent on library research.

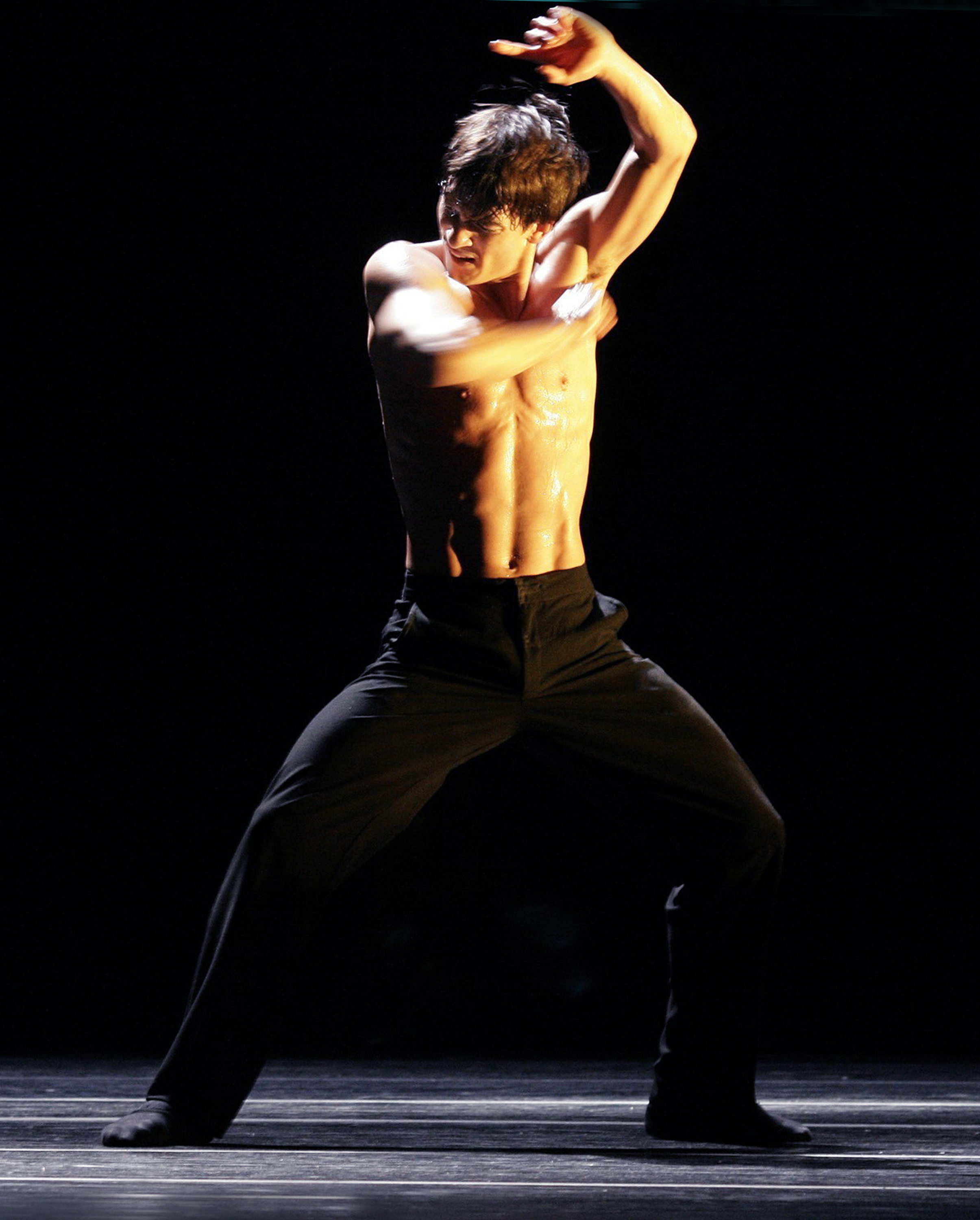

Matthew Rushing in Ronald K. Brown's Dancing Spirit

Photo: Paul Kolnik

By far the best of the new works was Ronald K. Brown's Dancing Spirit, its title taken from Jamison's 1993 memoir, its score assembled from jazz, rock, and fusion music of then and now. Brown has created works for many companies in addition to the Ailey and maintains a troupe of his own, Evidence. Despite Brown's slew of commitments, Jamison's successor would be a fool not to co-opt him for the position of Choreographer in Residence at the Ailey. The move would benefit all concerned.

Dancing Spirit opens with the entrance of a peaceable man in white, who establishes an area of calm in a teardrop spotlight. A woman follows him, then another man, and so on. The slow procession has a ritualistic air--Brown's dances are often spiritual--and you breathe deeper as it continues.

Then a punchier rhythm invites additional dancers into the stage space. Arms are quietly raised to the heavens, then strike out forcefully on the diagonal. The group's movement suavely incorporates elements from the dances of the African diaspora and American modern dance; there's a touch of jazz here, a hint of ballet there. Torsos ripple, hips sway, inviting the viewer imagine her- or himself part of this community, which depicts the realm of the spirit while giving the Earth its due.

Even so, the loveliest and most remarkable quality of the choreography is Brown's confidence (that of a born architect) with the groupings and patterns the bodies make in space. A penultimate section is all throbbing percussion, but just when you think this climax will escalate until it sets fire to the theater, the dancers arrange themselves gently into a horizontal line downstage, standing still and self-possessed.

NOTE: The above article, commissioned by Voice of Dance, comes to you so late because VOD has held it without posting it since its timely submission on December 24. Not only has VOD failed to post the piece, it has also failed to pay me for it and for my previous article on its site, "Morphoses Falters," a review of Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company, which it did post. Such is the lot of the free-lance dance writer.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Pacific Northwest Ballet / Joyce Theater, NYC / January 5-10, 2010

Pacific Northwest Ballet, based in Seattle, is making its first New York appearance in 13 years with a program of four ballets, three of them new to our town. The more substantial of them are Twyla Tharp's Opus 111 and Benjamin Millepied's 3 Movements. Astonishingly, not a one is by George Balanchine, whose works have long been the most significant part of the troupe's astutely chosen repertory.

Founded in 1972, PNB was subsequently led for nearly three decades by the husband-and-wife team Kent Stowell and Francia Russell (he got top billing, but she's the most famous); earlier, both made their performing careers with the New York City Ballet. Russell took charge of PNB'S ever-growing Balanchine acquisitions. Her productions, known to East Coast ballet fans largely by hearsay, were praised for their accurate rendering of the choreography. I saw a couple of them and found them rather dry and dull--the work of a devoted accountant.

Peter Boal, celebrated for the purity of his dancing as a principal with the City Ballet, took over from Stowell and Russell in 2005. You'd think he'd be the first to include Balanchine in an engagement taking place on Balanchine's "home turf"--if only to show the competition how well, how distinctively his company dances the master's creations. Just last year, Miami City Ballet, directed by another important NYCB alumnus, Edward Villella, did just this--thrillingly.

Perhaps Boal was more interested in showing the Tharp and the Millepied works because he commissioned them for the company--both in 2008.

Pacific Northwest Ballet in Twyla Tharp's Opus 111

Photo: Angela Sterling

Tharp's Opus111, named for the Brahms string quintet to which it's set, is easily the best dance on the program. With its cast of twelve, it shows off the soft grace of the PNB dancers and rarely hints at the punitive physical extremes that have been typical of Tharp's major works for years now and the way-cool slouchiness that so disgruntled old-school observers of her early masterworks. Yes, the choreography abounds in Tharp's daredevil lifts and maverick twists of the classical ballet vocabulary, but these elements have been gentled--either by Tharp herself or by the way the PNB dancers perform them--and no longer come across as brash challenges to officialdom.

The main characteristic of Opus111, though, is a complex braininess that has been typical of Tharp from Day One. You can hardly parse it on a first viewing, though you can sense that it underpins the ballet's structure. Here, the choreographer revels in mirror-imaging of all sorts and related complementary juxtapositions, as demonstrated in the lyrical second movement, where the dancing of the main couple is suavely accompanied by, or set off against, the movement of two auxiliary trios and, if I remember rightly, another pair. Tharp operates so smoothly here, she made me think of the secondary groups as the principals' landscape.

The women in the piece wear soft slippers rather than pointe shoes, ballet's traditional way of indicating that they are people of the earth, not members of the aristocracy. And folk motifs, which occur briefly and subtly throughout the piece (echoing qualities in the music), emerge full-force in the finale, where every foot is robustly flexed--as classical ballet imagines peasant-dance style--and with the performers arranged downstage in two parallel lines that stretch from one side of the proscenium arch to the other, presenting themselves guilelessly--fresh-faced, forthright, and smiling.

Opus 111 isn't likely to be considered a landmark in Tharp's career, but for me it saved the evening.

I don't know what to make of Benjamin Millepied--a City Ballet principal--as a choreographer. Ambitious and diligent, he "improves" doggedly, learning how to bring off one basic task of choreography after another. But he hasn't yet made me want to see one of his dances a second time. Au contraire.

Pacific Northwest Ballet in Benjamin Millepied's 3 Movements

Photo: Angela Sterling

Of late he's been teaching himself to manipulate large numbers of dancers effectively. Earlier, I saw another of his exercises in this vein that resulted in a frantic, blurry mess, like rush hour at Times Square. But 3 Movements, set to Steve Reich's relentless Three Movements for Orchestra and featured as the second "big number" on the Joyce program, was as clear as could be; indeed it looked as if most of it had been designed on graph paper. Like all the Millepied's works I've seen, this one seems hollow in the sense of having no interior life, no imaginative vision, no notion of what makes a ballet unforgettable. The answer lies beyond the realm of efficiency.

The Joyce program is completed by a pair of smaller pieces, no doubt audience pleasers though hardly distinguished works of art. Edwaard Liang's Für Aline, a duet created in 2006, is set to a radically sparse score--single notes separated by silence, constituting a fragment of melody that haunts the memory--by the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, a favorite among dance makers with a melancholy bent.

Liang gives us a young man apparently unable to relinquish his obsessive memory of the woman he loved, who has died. For him, she exists in the present--as exquisite and delicate as ever, moving with a "being beauteous" quality. Unfortunately, Liang depends on bits and pieces he's (and we've) seen and liked in other, better, choreographers' work, without giving them a meaningful new context and seems devoid of invention when left to the his own devices. What's more, the mood of his piece is woefully sappy. Still I did appreciate the moment in which the lost beloved suggests that she--though presumably now dwelling in the Elysian Fields--misses her partner as much as he misses her.

Pacific Northwest Ballet in Marco Goecke's Mopey

Photo: Chris Bennion

Marco Goecke's 2004 male solo, Mopey, is set to music by C.P.E. Bach, then the theatrical ploy of no sound at all, then to raucous sound from The Cramps. It describes an alienated youth who suffers, violently and picturesquely, from (a) drug addiction; (b) spasmodic hyperactivity caused by Attention Deficit Disorder; (c) an unspecified form of psychosis. Choose one or all of the above. Because of its length, perhaps, and its physical challenges (sheer endurance being just one them), it's made to impress but not, unfortunately, to express anything beneath the surface.

Given the dubious worth of these two pieces, Boal surely would have done better to replace them with--if not a Balanchine contribution--at least one of the several works of Jerome Robbins that he has acquired for PNB in the course of his tenure.

As for PNB's dancers, they make a very good ensemble, but even the best among them, charged with leading roles, lack the ability to thrill your eyes and heart, to "own" the stage as real stars do. This capacity may come with time, but then a lot of time has already passed.

What really broke my heart was the sight of Carla Körbes, justly adored by the New York audience when she was with City Ballet, although she never received the roles her ballerina-qualities seemed to deserve. Now a principal with PNB and dancing leads in three of the opening-night ballets at the Joyce, she looked hampered both by embonpoint and, far more telling, a failure of desire.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary