Seeing Things: December 2009 Archives

Chunky Move: Mortal Engine / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House / December 9-12, 2009

Chunky Move, founded in 1995 and still led by Gideon Obarzanek, comes to us from Down Under, or Oz, as some people call Australia.

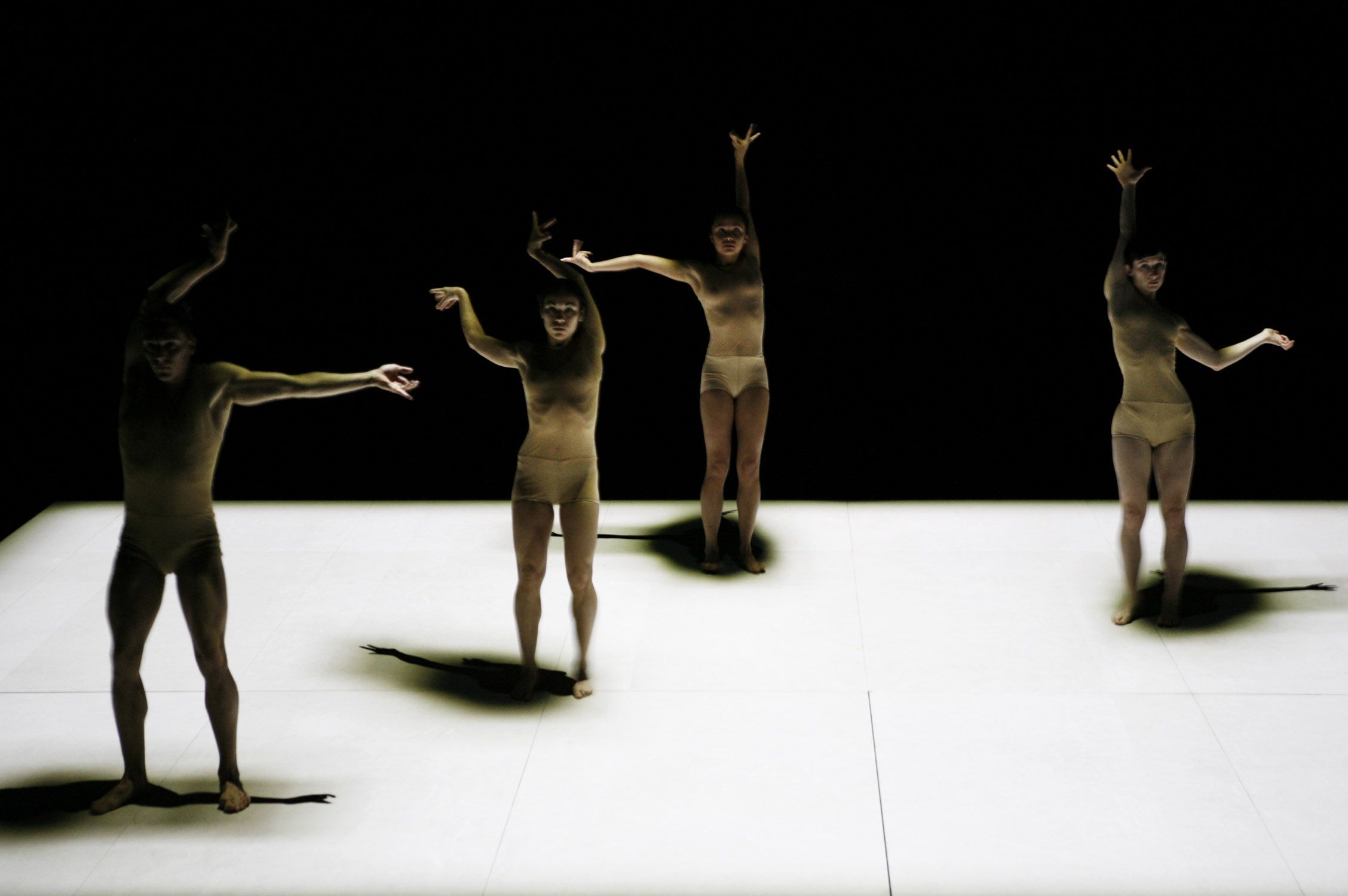

Chunky Move in Mortal Engine

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The troupe's name indicates its original purpose--to invent dance productions that contrast with the rarefied artifice and elegance of ballet. (Originally trained in that classical genre, Obarzanek, who masterminds the group's works, is decidedly in recovery.)

Of the Chunky Move programs I've seen in New York, my favorite is Tense Dave (a collaboration by Obarzanek, Lucy Guerin, and Michael Kantor), awarded a Bessie in 2008.

Especially after seeing Mortal Engine, I'm mystified by the fact that the items in Chunky Move's repertory are so dissimilar, so different in subject, style, and tone to one another. This may be (at least in part) the result of collaborative creation. Often the makers of the movement, the set (in Tense Dave, for instance, the "stage" consists of a huge compartmentalized turntable), as well as the light, sound, costumes, and electronic gimmickry have near-equal prominence. I'd bet, too, that the performers have a lot to say about what goes on; though silent, they look articulate.

Mortal Engine is a giant step away from Tense Dave; it doesn't even call itself a dance. According to the press release, it's a "multimedia performance work using movement- and sound-responsive visual projections to portray an ever-shifting, shimmering world that defies the limitations of the body. A web of lasers and video projections react to the dancers' every movement, creating a layer of virtual choreography superimposed over its physical manifestation." Fancy talk, but you get the idea. Needless to say Mortal Engine has no definitively fixed form; it's new every night.

So what actually goes on in the one-hour (and too long at that) intermissionless piece? On a huge tilted floor, raked toward the audience, a remarkably supple, mostly recumbent woman in a sheer-topped gray leotard curls and splays her body as if it were well-nigh boneless. After a long passage of this bravura elasticity, she's approached by five crawling bodies bathed in inky shadows that appear to menace, even swallow, her. A section of the tilted floor is then engineered to a near-vertical position and she stands alone before it, illuminated by light so bright your eyes cringe as you watch. Next, the light fragments into a phalanx of splinters that surround her. The whole business reminded me of Joan of Arc's trial and burning at the stake. Wondering why I had to find a familiar narrative for stage action that its creators surely conceived as abstract, I realized that what I was being offered was simply insufficient. The media were multiple, as promised, but the result was thin--and trite to boot.

In another "scene" a man and woman move as if they're making love, at first calmly, with a voluptuous laziness, but then in a confusion of thrashing arms and legs. Apparently, not even love can save the day.

And so it goes. Shadows are always present, in one way or another, threatening vulnerable victims. Often these "ghosts" leave their image for a while, even after the figures casting them have shifted position. Later, broken down into confetti-size particles, the dark matter seems to be an element the bodies exude, infecting the world around them, or one that has inexplicably materialized from nowhere to entrap the bodies present.

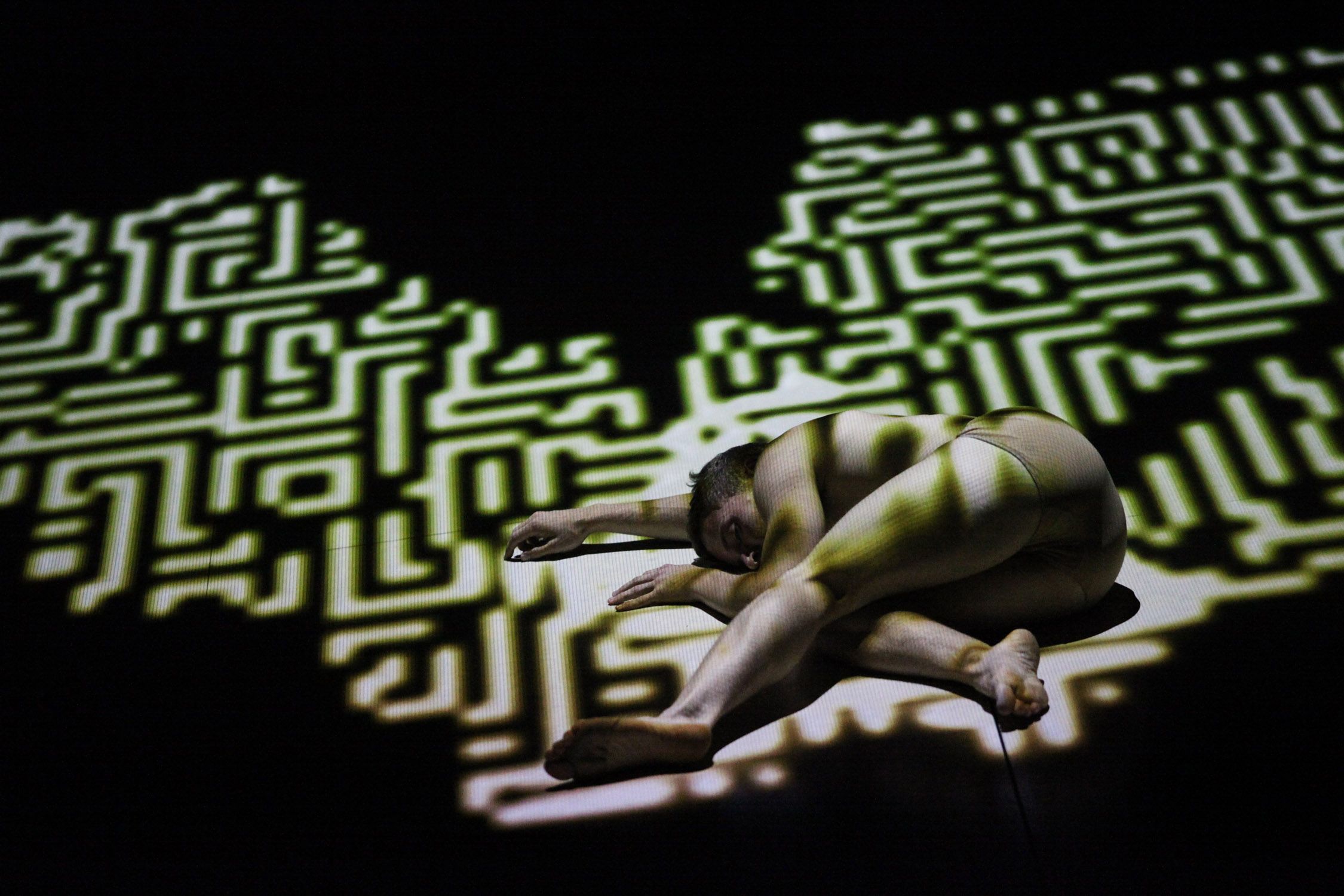

Chunky Move in Mortal Engine

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The frequent alternative to these versions of dark is blinding light--sometimes as whole-body haloes or pictographs of death by electric shock, at others as patterns that trap the bodies in an inescapable maze. Sections are given over to the light alone, which forms swiftly morphing linear patterns. All the while, the sound hums, growls, throbs, buzzes, or emits static--as if it were intent upon drowning out reasonable discourse or the music of the spheres.

Chunky Move in Mortal Engine

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Finally, the show moves into a very Ayn Rand apocalyptic mood. A fog spills over the bodies onstage and invades the auditorium, accompanied by a faint smell of incense (or is it hot cinnamon toast?). A triangle of green light divided into beams and topped with a glaring spotlight (a postmodern Christmas tree sporting its star?) follows the path of the fog. After this business is given extended play, a lone figure goes stumbling towards the intense green light atop the triangle, as if to its perilous destiny. Then, in an abruptly conjured peach-tinted glow, two figures embrace. Oi vey!

It's possible that Chunky Move's productions fall into one of two opposed categories: Down Home or Outer Spacey. Tense Dave belongs to the first group, showing the messy drama of a confused or obsessed human being awkwardly making his way through life. Mortal Engine--cool, objective, and galactic--reminds me of nothing so much as Alwin Nikolais's dances. Nikolais operated in the pre-electronic theater days of the mid-twentieth century, but all the concepts are the same as Mortal Engine's, in particular the treatment of the human body as just one of many equally fascinating elements in the universe, such as mercurial effects of sound and light. Granted, the result is occasionally magical, but it hardly provides emotional satisfaction.

© 2009 Tobi Tobias

By Christopher Caines, guest contributor

Imagine that Sol Hurok had telephoned the director of a slightly down-at-heel, raggle-taggle, time-traveling vaudeville troupe one day and said, "Parker! Listen: I need a Christmas show! A Nutcracker! Pronto! My Russians canceled. I can get you a couple weeks of one-nights. If you deliver, maybe we can make it an annual thing. Can you do it?"

Members of the Bang Group in Nut/Cracked

Parker looks around the studio. The troupe has a ragbag assortment of old props--some beat-up top hats and tails, a red feather boa, a fan, silk flowers, sunglasses, a flashlight, a tiny fake Christmas tree for holidays on the road, a stack of maple-leaf-red knit watch caps left over from a winter tour to Ontario, plus bubble wrap to pack it all up in. There's a Chinese takeout container from somebody's lunch. Tap shoes? Got 'em. Plus a trunk full of battered toe-dancing shoes the dancers found, left behind on a railway platform by one of the Ballet(s) Russe(s) on a whistle-stop tour that Parker's group crossed paths with in Des Moines or somewhere. Luckily the troupe does have the right music: a stack of 78s including a set of this Tchaikovsky fellow's Nutcracker Suite--though a few of the disks are scratched, broken, or missing. But luckily the stack includes some novelty arrangements of the same music that might fill the gaps. Best of all, the troupe has a bunch of terrific dancers: many shapes and sizes--not like a corps de ballet--but all strong movers, smart, ace rhythm, big heart. Maybe a few old friends might be enticed out of the stables as guest artistes, and maybe Parker can get some kids from somewhere--Christmas show, gotta have kids. The Nutcracker . . . it's about this wooden doll, right . . . ? "Sure," Parker says to Hurok. "We can do it." And so, in my fantasy at least, David Parker and the Bang Group's Nut/Cracked was born.

In fact, Parker's wryly affectionate take (and double-take) on the holiday ballet classic was not commissioned by Hurok, but by an Italian producer in Genoa in 2003. The piece was next presented in an abridged form at Dance Theater Workshop in January 2004, and returned for a box-office-record-setting two-week run at DTW the following December. Since then the Bang Group has performed the work (in many versions, with casts of varying sizes, on stages ranging from the tiny to the large) around New York City and the country for seven seasons--adhering to the spirit, if not the letter, of the laws of vaudeville. Nut/Cracked has racked up more than 150 gigs, which is remarkable for a non-ballet company's Christmas dance show, and the work returns to DTW for three matinees starting December 13. The piece often includes guest dancers, and this year, I will be one of them, lending a hand (or a hoof) to an old friend and colleague by appearing in a couple of sections.

I readily agreed when David asked me to dance in Nut/Cracked because I had laughed so hard watching it in 2004. Not only that, but I grew up in a small Canadian city that had no Nutcracker--in my youth, North America still had such cities--and I neither saw nor danced in a production of the ballet as a child, unlike legions of my fellow dancers (including, over the years, many members of my own company). I've always felt a bit deprived by my Nutcracker-less childhood. That ballet, of course, opens the magic doorway into dreaming of dancing, and dancing, or a least dance-going, for countless millions. But not for me. At long last, I'll get to dance in a Nutcracker.

Sort of. For while Nut/Cracked is not a Not-Cracker--that is, it is not an anti-Nutcracker--it is nonetheless not The Nutcracker. Although all the music for the show comes from or is adapted from Tchaikovsky's score, Nut/Cracked sets aside entirely the ballet's story and characters: no Marie/Clara/Masha, no Fritz, no Herr Drosselmeier, no Mouse King, no Dewdrop or Sugarplum Fairy or Snow Queen--no Nutcracker, even. Still, they all hover, like ghosts, in the work's shadows. For Nut/Cracked is a palimpsest: knowledgeable viewers will see through the nut's cracks to the traditional ballet, and to ballet conventions and mannerisms that are being sent up in some of the numbers. Yet the piece does not rely for its comedy on an audience that knows The Nutcracker at first hand and will get all the to-the-trade jokes. Nut/Cracked's humor ranges from the insinuating through the subtle to the very broad, often all at the same time; you can enjoy it no matter what you know about ballet or any other kind of dance, and the work is both good fun for those who adore Christmas, oddly satisfying to those who hate the season, and a tonic for people like me who simultaneously love and dread it.

Parker is not at all the slightly naïve entertainer I have depicted in my fantasy genesis story of his work, but a highly self-aware artist; moreover, his take on the tale is, in Schiller's terms, a sentimental rather than a naïve work--though in our modern sense of the word, it is not sentimental in the least. Indeed, Nut/Cracked is sly, occasionally arch, and packed with knowing allusions not only to traditional stagings of the score but to other ballets as well--not to mention revivals, quotations, paraphrases, and fond parodies of, among other things, modern and "postmodern" dance, breakdancing, clogging, soft-shoe (in bare feet), Saturday Night Fever-style disco, and the all but lost art of toe tap. The work revels in its mongrel vocabulary, its hybrid vigor, its inclusive taste. The dancing overflows with jokes (many of the in- and/or running varieties), slapstick, gags, pratfalls, visual puns--and a bisl of shtikele too: the silk bouquets in the "Waltz of the Flowers" induce an allergy outbreak among the cast; the skating rink where the "Waltz of the Snowflakes" is set has some treacherous patches the Zamboni must have missed. The traditional Nutcracker is also a comedy: a dramatic entertainment that ends, at least symbolically, in a marriage (as opposed to one that ends in death, which would make it a tragedy). Yet Parker's Nut/Cracked represents a different order of comedy entirely.

In order to prepare properly for my roles, I thought it might be wise to revisit the "real" Nutcracker. Luckily, I live in New York City, and thus can go straight to the top: Mr. B. And so I found myself in the newly renovated David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center on opening night, the Friday of Thanksgiving weekend, at New York City Ballet's George Balanchine's The NutcrackerTM, as the company currently bills its annual holiday spectacular, a ballet I had not seen for several years. Premiered in 1954, Balanchine's Nutcracker is not the country's oldest full-length version (the San Francisco Ballet holds that honor, with a production originating in 1944), but it is acknowledged by many critics and balletomanes to be the greatest, not to mention the direct source or inspiration for countless other productions. Balanchine's is likely also the closest in spirit and in detail of dance and mime to the original, premiered in 1892, with a scenario devised by Ivan Vsevolozhsky, director of Russia's Imperial Theaters, and his ballet master, Marius Petipa, for the Maryinsky Theater in Saint Petersburg, but choreographed by Petipa's assistant, Lev Ivanov, when the master fell ill.

Viewing The Nutcracker again I was struck above all by its moral seriousness, lightly borne. The choreography, and NYCB's mise-en-scène in most ways, constitute an exquisitely crafted entertainment; it's easy to see why families who can afford it make the ballet an annual holiday tradition. Yet the sense that the ballet offers more than entertainment is present from the overture, not only in the way that the music vaults across the whole range of emotion in the score, but in Rouben Ter-Arutunian's frontcloth, which shows an angel reaching with both hands toward a star. It is worth remembering that this Christmas star, which reappears above the towering pine forest in the last measures of the climax of act 1, the "Waltz of the Snowflakes," to guide the child heroine and hero into the visionary realm of act 2, glisters not over Toys"R"Us: it shines over the Savior's manger bed in Bethlehem. And although all of Balanchine's work persuades me that the Virgin Mother of God meant much more to him than the Father or the Son ever could, nonetheless The Nutcracker remembers at some level that Christmas is not only a holiday, but a holy day. We should never forget that Balanchine was a man of faith, and not faith in music alone, but a professing member of the Orthodox Church. How else to explain the Russian child angels, each bearing an unadorned miniature Christmas tree, who glide about the stage on tiptoe in patterns of immaculate symmetry with their stiff conical skirts swaying like church bells, to welcome Marie and her little prince to the Land of Sweets?

New York City Ballet performs George Balanchine's Nutcracker, with three generations of characters in the Party Scene

Photo © Paul Kolnik

Balanchine's Nutcracker, like the original Maryinsky version, is a ballet for and about children, and also a work designed to give children of all ages seriously training for the profession roles to perform. Yet the vital purpose of childhood, in Balanchine's world, is to grow up, to learn to be an adult. In act 1, we see the children who are invited to the Christmas party at the Stahlbaums' cozy bourgeois home--gemütlich and gutbürgerlich both--as they are schooled in adult ways, above all, by dancing. At first, parents and children dance their quadrille-like figures together, with the adults guiding their offspring through the steps and patterns and showing them the appropriate manners: how to approach a partner, how to bow, how to offer a hand, how to accept one. Thus instructed, the children are soon able to dance unattended at stage left while their parents dance opposite. The children's realm is a miniature parallel replica of the adults'. Eventually, the two groups evolve from unison to counterpoint, as the children dance their own independent figures without guidance. Metaphorically--or more precisely, metonymically--the parents have begun to impart an entire aesthetic and moral education. (The theme is underlined in the mime action too, as Marie's scene-stealing naughty younger brother, Fritz, is repeatedly scolded for his misbehavior.) Later, when corsages are distributed to the males of the assembled company, the little boys gravely offer them to their partners, just as their fathers do. As Arlene Croce wrote in 1974, Balanchine's act 1 is "taken for granted because it's so simple and 'has no dancing.' It contains the heart of his genius."

In act 2, Marie and Drosselmeier's nephew, restored to himself after being transformed into the Nutcracker Prince (the nutcracker doll brought to life to do battle with the Mouse King and his army), do not dance, but sit enthroned high above upstage center to watch the divertissements Balanchine has devised, which include young dancers drawn from many levels of the School of American Ballet. Symbolically, act 2 is a wedding celebration; we remember the crucial bit of mime in the party scene in which Drosselmeier (as least as portrayed by Robert LaFosse, whom I saw in the role) reveals to the audience that he is plotting the union of Marie and his nephew, and the way the two little dancers walk up the aisle through the evergreen cathedral at the close of the snow scene. But Marie is only eight years old. Though she wears a tiny bridal veil throughout act 2, she is celebrating, not her marriage to her gallant young friend, but the future promise of it--Marie is playing house on a very grand scale. Dancing functions in The Nutcracker just as the ballet itself functions within the repertory of a company that maintains a school--like City Ballet, and like the Maryinsky: as a realm of necessary experience, yes, but above all as a realm of noble aspiration. Below them on the stage, Marie and her prince behold dancers of all ages, from the tiny Polichinelles (darling French clowns) who emerge from under Mother Ginger's skirts, through the adolescent corps of Candy Canes, to Dewdrop (one of the work's two ballerina roles) and her Flowers. The long path that leads from early lessons to apprenticeship to mature artistry is laid out, step by step, in a series of images of dancerly accomplishment. Yet Balanchine also vouchsafes to Marie secrets of adult life that no child could ever consciously understand, which she can only keep and ponder in her heart, as the Gospel of Luke tells us Mary meditated upon the events of Christmas night. "The annual Nutcracker has become a liturgical event," Croce wrote in 1969, "one whose deepest significance we celebrate in our hearts and try to keep our children from knowing."

Sara Mearns and Charles Askegard as the Sugarplum Fairy and her Cavalier, in the New York City Ballet's production of George Balanchine's Nutcracker

Photo © Paul Kolnik

In Balanchine's theatrical universe, to become a dancer--and, especially, a ballerina--is the noblest of all human destinies. It demands great sacrifice; in a certain way, it may even demand the sacrifice of childhood itself. Moreover, all children must at some point leave childhood behind, and while they may know or guess what that mysterious leave-taking will look like, they cannot know how it will feel. In the music for the Sugarplum Fairy's grand pas de deux with her Cavalier--and only here, in the entire ballet--Tchaikovsky allows adult passion to brim, overflow, and cascade as from a dammed lake of tears. The plangent melody, at first ruminating, then soaring, is deeply shaded by tragic knowledge of indefinable loss. As the melodic motif contracts, rising urgently in pitch and volume, striving to cadence, then crests and wanes, we recognize too the tremor of erotic knowledge. "Listening, we see, we touch," Croce wrote in 1986, "until we hardly know whether it is the tympani we hear or the hammering of our own hearts." Tellingly, perhaps, this is the only segment of the score of those that Parker sets that his comedic purposes forbid him to approach on its own terms (whereas he otherwise highlights rhythmical details of the score's music-box-like textures that strictly balletic treatments sometimes blur), and for which he must resort to Nut/Cracked's sole truly sardonic, even caustic ironies. Only classicism at its purest may reach for the star Tchaikovsky hangs high before us.

When I write that Nut/Cracked represents a different order of comedy from Balanchine's Nutcracker, and that it is a work of Schillerian sentiment, I mean that the two works are suffused with different kinds of self-awareness. The Nutcracker is self-enclosed within the visionary realm of classicism. Gleaming through Balanchine's ballet are reflections and refractions not only from the Petipa-Ivanov original, in which Balanchine himself danced as a child, but from the other great Tchaikovsky-Petipa ballets, Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty, as well as Sylvia and Coppélia, whose scores by Léo Délibes Tchaikovsky revered. Indeed, the whole history of ballet as a theatrical art form and a spiritual endeavor shines through the fabric of Balanchine's choreography, above all in "Snow," "Flowers," and Sugarplum's pas de deux. There is something of Dr. Coppélius in Drosselmeier, with his giant mechanical dolls, for example, and of Swan Lake's Von Rothbart too. Sugarplum's adagio echoes Sleeping Beauty's "Rose" adagio. Balanchine's Nutcracker is a duplicate in its structure of his Midsummer Night's Dream (which ballet-goers may see at NYCB immediately after The Nutcracker closes in January--a nice programming touch): a densely plotted first act that leads to an all-divertissement second act in ritual celebration of marriage; The Nutcracker's act 2 likewise echoes the wedding dances that close The Sleeping Beauty and Sylvia. I could go on. The cultural background of The Nutcracker is ballet itself.

The background of Nut/Cracked, however, is in part the reception of ballet in the United States and the role that The Nutcracker has played in that story over the course of the last century. (Americans' first exposure to any part of the ballet was in a production entitled Snowflakes starring Anna Pavlova in New York in 1915: the habit of devising spectacles including excerpts from The Nutcracker originates from within ballet, not outside it.) The pop/jazz treatments of Tchaikovsky to which Parker sets the first half of his evening (corresponding structurally, but not thematically, to Balanchine's act 1 before the "Snow" scene) offered him a side door into Tchaikovsky's imposing score via the fiercely syncopated percussive vocabulary that is this tap dance-based choreographer's native dialect. The records also roughly chart the naturalization of the immigrant European aristocratic dance form in the United States, as they range from charming, daffy kitsch (smooth choral arrangements with cute lyrics by Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians), to playful but serious jazz recompositions by Raymond Scott, Glenn Miller, and Duke Ellington, who address Tchaikovsky more or less as an equal, as a fellow composer.

The cultural background of Nut/Cracked is equally the American (and worldwide) Christmas Industry, which of course includes the country's 300-plus current productions of The Nutcracker--and for New Yorkers and our holiday tourists, includes Balanchine's masterpiece. In this sense Parker's work has what I can only call a meta-theatrical dimension. Nut/Cracked acknowledges the annual consumer frenzy of Christmas, complete with pandemic bad faith, commodity fetishism, stress, envy, greed, disappointment, shopping and wanting and getting and not getting and returning and "re-gifting"; gruesome Xmas Muzak that starts in October; compulsory contributions to the economy and equally compulsory fun; pious, prefabricated sentiment; the ritual sterile debate about the season's "commercialism"; the obscenity of year-round Christmas stores; and such traditions, more honored in the breach than in the observance, as getting blasted at the annual office party and making a pass at a co-worker.

Members of the Bang Group in Nut/Cracked

Beyond its craft--the flowing ensembles, the meticulous development of gestural motifs, the intricate percussive counterpoint, the close attention to the music's structural changes--the best thing about Nut/Cracked is its good spirit: a lot of "Let's put on a show!"--but something more, too. For all its wisecracking, Nut/Cracked reveres ballet, which remains within the work an ideal realm of aspiration--perhaps more glimpsed than seen. Classicism is cracked, but not broken. The dancers are forever crashing nimbly to the floor as the choreography, turning on a dime from some cherished Cecchetticism secretly embedded in a buoyant petit allegro enchaînement to a waltz-clog or the Charleston or the Funky Chicken, pulls the flying carpet out from under the dance. More than anything else, Nut/Cracked makes fun of itself, and in so doing allows us to find humor in the predicaments we put ourselves through every year at Christmastime.

Christopher Caines is artistic director of the Christopher Caines Dance Company. He is currently at work reviving ARIAS, the evening-length work with which he founded his ensemble in 2000, for spring 2010 performances.

David Parker and the Bang Group perform Nut/Cracked at Dance Theater Workshop, December 13, 19, & 20 at 2 p.m. New York City Ballet presents George Balanchine's The Nutcracker at the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center through January 3.

© 2009 Christopher Caines

It isn't easy, trying to buy clothes now that the years have beset the body with flaws. You can't find garments that cover all of them except, of course, a shroud. But not yet. Sometimes I think I should wear one of those Asian or African or Indian outfits that simply swathe you in fabulous fabric. Then all I'd have to do is develop an undulating walk for allure.

The clothes of my childhood were a different matter. Some of them were memorable for the pleasure they gave me, others because they--I really mean this--left permanent aesthetic scars.

Younger, I had a blue and white dotted swiss summer dress. Dotted swiss is a gauzy material with tiny raised dots as if each one had been embroidered separately. The dress had capelet sleeves like a small pair of fairy's wings that fluttered as you moved or just stood still in a June breeze. Its image is incised on my memory so vividly, at times I think I could go to my closet and find it there still, unchanged, though I have changed so much.

Prepubescent, I had a nubbly wool winter coat in aubergine (you know--deep eggplant purple) that sported big, round, faux-leopard skin buttons and, at the neck, a bow tie in the same leonine fabric. The bow tie was a bit much and my mother and I soon agreed to remove it, but the coat--odd and striking, in its own peculiar way wonderful, a coat fit for the daughter of an artist--was typical of my mother's taste. My mother's "profession" was housewifery, but she had the soul of an aesthete. I felt uneasy about the coat at the age I wore it. Only later did I realize it was unusual--even stunning.

Though she produced a daughter who can barely sew on a button, my mom had a phenomenal gift for adorning a plainly cut, monotonal jacket or skirt with her own vibrant designs, which incorporated appliqués, bead work, and embroidery. When ordinary girls were indulging in poodle skirts, a popular cliché that, in its store-bought version, sported a single felt poodle attached to a leash meandering to the waistband, (curling like the telephone cords we had back then), my mother produced a ravishing concoction for me. It was a radiantly colored and ornamented garden of bright blooms that went all the way around a widely flared skirt without once repeating itself.

Before that came the fad of Mexican jackets that sported run-of-the-mill, machine-produced on-the-cheap cut-outs of cowboys, cacti, sombreros, and a bucking bronco with little kick to him. You should have seen the detailed and exquisite handmade version my mother made of the theme. It looked as if it actually spoke Spanish.

I treasured these garments. They made me feel special. But when I outgrew them, my mother insisted that I pass them on to less-fortunate children in the neighborhood, for charity's sake. To this day I harbor, guiltlessly, the uncharitable wish that I had insisted on keeping them, just to look at. They were that wonderful.

A huge room in Aunt Eva's house, devoid of furniture and decoration, was devoted to rack upon rack of these garments, in the sleaziest, most tasteless patterned fabric imaginable or in a pastel-hued fake satin that made my skin crawl, each item executed in infinite multiples and hung according to size (2 to 12), the simplest seams bunched and crooked, as if the good Lord had neglected to teach his servants the rudiments of operating a sewing machine.

But that wasn't the worst. Aunt Eva gave some of these offerings to me, too, with the patronizing smile of an elder conferring a special sweet upon a child. And my mother actually made me wear them, not just once in a while to please Aunt Eva when we visited her--which we were obliged to do weekly, because Grandma lived with her--but as a staple of my wardrobe.

Visits to that room, from whence the clothes were shipped abroad, remain with me to this day as a waking nightmare. Oh, those poor charity children who would have to wear such dreadful garments every single day--and gratefully to boot!

The year I turned twelve, it was unseasonably hot on my birthday, and my mother had invited nine of my girlfriends to a formal lunch she prepared and served, pretending not to listen to our adolescent conversation, replete with "secrets" and giggles. Of course, despite the heat, I insisted upon wearing an outfit from my new fall-winter finery, occasionally wiping the resulting sweat from my brow, as unobtrusively as possible, with my linen table napkin. And every year I wore one of Uncle Isaac's new ensembles on the first day of school. I may have been uncomfortably warm, but I felt elegant, elevated above the tawdry, certainly, but also above the commonplace. I think it was from the refined excellence of those clothes that I learned to recognize and seek out, when I later chose my own, the understated design and meticulous workmanship that gives an everyday wardrobe distinction.

Once embarked upon lowering my clothes budget radically, I found that, given my trade as a professional dance observer and my keen interest in the visual arts, I was good at spotting the rare gem lurking on the crammed racks and in the bottomless bins of dross. I found the searching a soothing activity, a veritable tranquilizer. And the finds were a thrill. Soon I realized I was exploring these low-end shopping venues for the sheer fun of the hunt.

The next step was creative, absorbing, and time-devouring--combining my finds into marvelous outfits that had a quality I've always cherished: a slight strangeness. For me, the obvious, no matter how luxurious or "correct," is deadeningly dull.

One of my favorite acquisitions was a copy of a Jean Desses dress made long ago for the lower-middle-class consumer. (Desses was a well-known French designer of the mid-twentieth century, who specialized in draped gowns fit for a Greek goddess.) My vintage copy, labeled with a credit to its inspiration, is calf-length, cut from navy crepe studded with tiny gray-metal stars and an occasional equally tiny rhinestone. Its draping is so subtle and complex--turned inside-out, the dress looks like the labyrinth Theseus negotiated with Ariadne's thread--it often takes fifteen frantic minutes to wriggle into it and the help of anyone who happens to be in the house.

Once, invited to a dinner party in Paris, I wore it with sheer black nylon hose that had a seam running down the back (you can still find these if you look hard enough), discreet costume jewelry of the twenties, and a well-worn Levi's jeans jacket. The ensemble created a quiet sensation.

Admittedly, I'm a sucker for anything strewn with minuscule stars that have a quiet gleam to them and appear ephemerally amid the folds or layers of fabric that serve as their sky. All this goes back to a Hallowe'en costume worn once by my schoolmate Judy Aronoff. (I refuse to call her Judith; no one did.) And first you have to understand that Judy's sixth-grade coterie of girlfriends faithfully arrived at her house early on school-day mornings and rushed up to her bedroom to watch her compose her outfit for the day, carelessly littering the ruffled white organdy bedspread with piles of fabulous discards or gazing intently into the mirror of her similarly-skirted dressing table. The rest of us dwelt in more Spartan environments, albeit more tasteful ones.

One Hallowe'en in our preteens, Judy--angelically blond-haired and blue-eyed, of course--was dressed as a fairy princess. Gently wafting a wand tipped with a crescent moon, she wore a white tulle gown, its skirt multi-layered like the long tutu of a Romantic ballerina, the under layers twinkling here and there with diminutive silver stars. One way or another, I've been trying to replicate that costume for more than half a century, hence my attraction to the after-Desses dress. Today I like to think that a child so spoiled and frivolous as Judy came to a bad end, but at the time she was a creature to envy and (though impossible) to emulate.

Under firm parental influence, I was headed for the Seven Sisters, the all-female colleges considered the equivalent of the elitist, male-only Ivies. Clothing my willowy figure for my interviews in a matching peach short-sleeved sweater and pencil-slim skirt seemed to do the trick. Or was it my top-notch academic record? Or my cultivated speaking voice and flawless, mama-bred manners? Or, my writing skill even on the tissue-of-lie essays on why I wanted to attend Vassar, Smith, Bryn Mawr, or whatever. I was accepted by every single college I applied to.

Neither of my parents was at home the afternoon the acceptances arrived and, without consulting them, I answered yes to Barnard, no to all the rest, and mailed my replies. This wasn't a rare access of rebellion but a crucial attempt to save my own life. Barnard, at least, was in New York, a hub of artistic activity, the town to which my spirit belonged.

After endless shopping, I found a perfectly fine dress that I could afford. It fit impeccably and, what's more, the green in its subtle weave matched my eyes. But the activity I pursued in it--convincing, which involved charming, CEO types, often elderly gentlemen, to give me money--made me feel like a prostitute. When the fund-raising period came to an end, thankfully with reasonable success, I burned that serviceable dress with glee, and have never succumbed to such a disguise again. It was my final attempt to wear what I wasn't.

"You'll catch your death of cold," my mother would say, sometimes angrily, sometimes resigned, whenever she glimpsed us at our ritual. Recklessly or not, we ignored her old-wives' science. "Colds come from viruses," we'd declare, tossing our long, luxuriant, adolescent locks.

These harmless clothes fads of adolescents should be respected, I think. They're fun. They're ephemeral. They're creative--a form of self-expression, albeit a group one. Surely self-expression is a kissing cousin of art.

Not so long ago I realized that I was still far more interested in writing than in wardrobe. Perhaps it was as a celebration of this belated bit of self-knowledge that I produced a book peaceably combining the two. It's called Obsessed by Dress. My editor calls it "a meditation on clothes." I think--at least I hope--it's strange and, perhaps, even wonderful.

© 2009 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary