Seeing Things: June 2009 Archives

American Ballet Theatre / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / May 18 - July 11, 2009

As celebrated in Russia as the Mississippi is in America, the mighty Dnieper River has accreted to itself a history, an atmosphere, and a mythology that reaches out to several arts--just as Mark Twain's masterwork, Huckleberry Finn, for example, is bound to the Mississippi.

Rushing to the Black Sea, the Dnieper passes through Ukraine, where Alexei Ratmansky, the new Artist in Residence at American Ballet Theatre, first danced professionally. Working to the Prokofiev score originally choreographed by Serge Lifar in Paris in 1932, Ratmansky put his singular ingenuity into his own version of On the Dnieper--a 40-minute ballet deriving its title from the music, which is considered his first official work for ABT. (A pièce d'occasion for the gala showcasing Nina Ananiashvili, which opened the company's May 18 - July 11 season at the Metropolitan Opera House, apparently doesn't count.)

Like all of Ratmansky's work that I've seen, On the Dnieper reveals the multiple influences on the formation of his aesthetic: training in the Bolshoi Ballet's academy in Moscow, then, when rejected for admission to the parent company, performing as a principal dancer with the Ukraine National Ballet, the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, and the Royal Danish Ballet, and choreographing for prestigious companies from St. Petersburg's Kirov Ballet to the New York City Ballet. For some four years he has been the artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet and one of its most inventive choreographers, at times taking his inspiration from Soviet-era ballets once thought better forgotten and making them utterly new and delightful, as with The Bright Stream. Now he has given up the leadership of the Bolshoi, with its soul-devouring administrative demands, to concentrate on his choreography.

Marcelo Gomes, Veronika Part, and Paloma Herrera in Alexei Ratmansky's On the Dnieper

Photo: Gene Schiavone

On the Dnieper tells a tale that the Romantics among us will believe in, others not. Sergei (Marcelo Gomes in the first cast, as are the others I name) returns from World War I to his beloved native village, indicated by weathered wooden fences, and the poignant springtime sight of blooming cherry trees just beginning to drop their petals. Though welcomed by his fiancée, Natalia (Veronika Part), he's distracted by Olga (Paloma Herrera), the community's vivacious beauty who has already developed a distaste for the fellow to whom she's engaged (David Hallberg). Parental figures and the young people of the village surround them, witnesses and judges as the plot plays itself out--with much self-recrimination on Sergei's part, and a selfless renunciation in favor of Olga on Natalia's part--to an ecstatic happy ending amid a veritable storm of petals, in which love conquers all. Yes, the program note is needed, but Ratmansky comes closer than most dance storytellers to indicating situations and, especially, deep feeling directly through his choreography.

What I like best about this ballet is its mood. Without making a melodramatic fuss, it supports the primacy of feeling, the respect for social behavior (at its moral base and in its formal traditions), and the wrenching conflict between those and the pull of the unexpected, often inexplicable, desires of the heart. It evokes the world as imagined by Tudor and by Chekhov.

Herrera, I'd venture to say, has never danced more eloquently. Finally, no doubt largely because of Ratmansky's ballet, she's realized that bravura technique cannot, alone, make a ballerina. In On the Dnieper she's exploring the realm of fusing her extraordinary physical prowess to a range of emotion. I hope the revelation of this possibility will carry through to the rest of her repertory; it could make her glorious.

Gomes, as always, has a commanding presence and here he lives up to the way he looks. At the same time, he is very affecting in his confusion and regret when he realizes that, for his own happiness, he must betray a sensitive woman he once loved. He needs only a little more detail and nuance, the patina a role acquires with time in the hands of a resourceful interpreter.

Part is just right for the reticent sensitivity of the abandoned, self-sacrificing sweetheart. I was touched by the moment she "gives" Sergei to Olga and they bow to her formally, then rush off, elated, to their future and she falls to the ground, unwitnessed in her anguish. She's the one character that made me think of her future--never marrying, I fantasized, becoming a nun or a nurse to the incurable, anything that would allow her to give her life to succoring humanity and expunge self-interest from her soul. The fact that Part's role is about emotions rather than famously difficult steps relaxes her frequently visible mistrust of her technical abilities, freeing her as a creature of the stage.

Hallberg, unfortunately, has a role that doesn't show him to any particular advantage, though he may, like many a wise dancer, make something better of it as he performs it more.

It was fun to see the seniors associated with the company (teachers, coaches, regisseurs, and the like) in the parental roles and wonderful to see a corps de ballet convincing in its robust dancing and in its walkaround roles as well, as witnesses, abettors, and benevolent spies--roles that make a community cohere.

For reasons I can't fathom, ABT's artistic director, Kevin McKenzie has returned to the work of the Canadian James Kudelka and Prokofiev's Cinderella score, after adding the choreographer's self-consciously quirky program-length version of the fairy tale to the repertory three years back, without much success.

Kudelka's 1991 Désir, given its ABT premiere on this season's Prokofiev program, is a plotless one-acter that uses the only four remarkable passages in the Cinderella score and two other numbers gleaned from the composer's Waltz Suite (reworked from his opera War and Peace). The dance is a pretty little thing, nothing more, admittedly useful to fill out a mixed-repertory program, but essentially insignificant.

Isabella Boylston and Cory Stearns in James Kudelka's Désir

Photo: Rosalie O'Conner

Two couples, one of them (Gillian Murphy and Blaine Hoven) opening the piece, the second (Isabella Boylston and Cory Stearns) appearing midway through, demonstrate joyous, fulfilled love, the first pair with an allegro pulse, the second in an adagio mode.

Misty Copeland and Carlos Lopez seem equally content, but they introduce a small ensemble expressing the doubts and tensions that arise between the sexes. Clusters of closely bonded young men and similarly united young women reflect the emotional difficulties of moving beyond a single-gender group. I think. This is not the clearest ballet in the whole world.

The movement is often soft and curving, over a firm ballet base. Nothing you haven't seen before. The dance would benefit from a wider, more inventive vocabulary.

There is no hint of a subplot behind the activities, several of which are incomprehensible. Why do the men repeatedly stretch out supine and stiff? Is this a premonition of death? What's the meaning of a repeated frozen arm position in which the women hold their full skirts bunched into a bundle in front of their bellies, like a wedding bouquet or its logical aftermath?

The best elements of the piece are the gorgeous costumes by Marjory Fielding (designed for the National Ballet of Canada production)--and the presence of Isabella Boylston in the first cast. Boylston has an uncanny calm that rivets the viewer's attention, even when she's tossed into the air and flipped backward by her partner. She has the face of a Flemish Madonna, a long, suavely proportioned body, and impeccable technique. In repose, she seems sculpted from marble; in motion, she's like that cool, noble stone magically endowed with fluidity. The fact that she has incredibly beautiful feet is underlined by the duet's finishing with her partner's extending his body along the floor to kiss one of them. The gesture is embarrassing, though, at odds with the formal tone of the duet, and entirely unnecessary. However, Boylston, still a corps de ballet dancer, deserves promotion to soloist rank on the performance of this role alone.

As for the costumes, the women's ankle-length dresses have a subtly composed palette of colors related to fuchsia and fire-truck red. They're set off by one in muted blue, another in intensely deep violet. The lavish skirts swirling in unison have a ravishing effect. The men wear casual t-shirts in shadowed tones that echo the women's gowns; they top workaday trousers of burnt sienna. The women are flowers; the men, the earth from which they spring.

One way to sell tickets to the ballet (or to sell anything else, for that matter) is to cause a sensation. In the States, the general public that comes to the ballet loves a sensation (for one thing, it justifies the cost of the tickets) and does its best to exaggerate the dimensions of one with wild cheers and applause during the performance, escalating into feverish standing ovations and bouquets from the spectators pitched onto the stage at the end.

Natalia Osipova in August Bournonville's La Sylphide

Photo: Marc Haegeman

During ABT's current season, the Bolshoi Ballet's Natalia Osipova--whose fleet, airborne technique took my breath away in 2005 in a solo in her company's Don Quixote--did a stint that I assumed to be a tryout for a larger guest association with ABT in the future, dancing the title role in two Romantic-era ballets, Giselle and La Sylphide.

Sensations, however, have only a tangential connection with artistry. Osipova's elevation (an issue of hip flexibility and leg power) and fleetness (foot articulation and power) are near miraculous. So much so that they have become phenomena--the feet working like hummingbirds' wings, for instance--not really the province of dancing anymore. Other parts of her body have been neglected: her face doesn't create the illusion of beauty that enhances a ballerina; her torso has no fluidity. She has also obviously been over-coached, a fact that destroys the childlike naturalness she had when I first laid eyes on her.

Giselle was the better of her two portrayals, thanks in part to the sympathetic partnering of David Hallberg. Still, with emotions coursing through her one after another at febrile speed, none of them lasted long enough to register and eventually add up to something coherent. And her continual grinning in Act I, as if this were an emblem of joyous, innocent love, should have been squelched at the first rehearsal. Her subsequent Mad Scene was reasonably good, if still immature.

In the second act, Osipova carried everything before her, seeming to fly and whirl at once when initiated into the ghostly tribe of wilis by a wonderfully malevolent Veronika Part. Still, the necessary change in movement texture between the live girl and the dead one who still retains her early passion for her lover, forgives him, and saves his life, was absent. I would guess she understands the difference intellectually, but can't yet make it happen physically. If, with time, experience, and sound professional advice, she still doesn't, her sensational effects are likely to deteriorate into mere circus tricks.

Osipova's La Sylphide was a disappointment. Her particular gifts do little to evoke the enchanting Bournonville style (which the Russians have never mastered and the Danes themselves are losing) in its phrasing, irrepressible ebullience, or charm. Her partner, Herman Cornejo, who seems to be able to adapt to any style he tries, was the hero of that performance.

June 27 saw Nina Ananiashvili's farewell performance with American Ballet Theatre. She took on the celebrated dual role of Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, the very thought of which can make a ballerina two decades younger than she quake in her pointe shoes. (Ananiashvili is 46.) The performance was extraordinary; I've never seen anything like it. Throughout, she demonstrated the exquisite technique that she has honed to perfection over the decades, but here, in the "white acts," she added little miracles like executing the mime passages, as in her relating her woeful story to Prince Siegfried (Angel Corella)--"my mother's tears formed this lake"--so fluidly it became the veritable cousin of dancing. Then, with a masterly containment of emotion so profound it was almost unbearable, though devoid of obvious acting, she made the dancing so refined it looked abstract. If classical dance can be transmuted in the equivalent of an Ozu film, this was it.

Nina Ananiashvili in Kevin McKenzie's Swan Lake, after Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov

Photo: Nancy Ellison

Instead of the cheap thrill of the full 32 fouettés (which, by the way, neither Margot Fonteyn nor Maya Plisetskaya ever mastered) she did a mere 24 as neatly as could be imagined and wisely quit while she was ahead. As if to make it up to the audience this slight diminishment of bravura, she executed a surprise carnival-style move in which Von Rothbart (Marcello Gomes at his sexiest) threw her high into the air to be caught in the deluded Siegfried's arms. The three repeated the feat on the curtain-calls, much to the delight of the madding crowd.

In the Black Swan act, Ananiashvili's rendition was tantalizing enough to contrast with her Odile, and some of her feats, though subtly executed (such as long balances in which she seemed to stretch up and out as on a breath) were remarkable. She made a quiet though compelling seductress, though, admittedly, her Odile doesn't seem as truly evil as her Odette seems good by nature's design.

The bows themselves, which seemed to run on hourglass time, rather than that of a stopwatch, constituted a ballet within themselves and were designed with unusual good taste. Even the single explosion of confetti, white and gleaming, looked like a falling star in a fairy tale instead of the familiar torn up paper drifting listlessly through a net. My favorite moments were the cast's applauding the ballerina, and she, them; Ananiashvili's personally presenting one white flower to every single corps de ballet swan; ABT's other ballerinas, in svelte black mufti, coming on to offer the heroine of the hour a long-stemmed blossom, followed by her male partners in the company, and, later, the artistic director himself, Kevin McKenzie, to whom Ananiashvili bowed low as she had to the Russian coach and to the former Kirov prima, Irina Kolpakova; the appearance of the ballerina's little copper-haired daughter, whose mom promptly enough shooed the child back into the wings after a bow or two; Ananiashvili's catching in one hand bouquets that the audience hurled at the stage, simply snatching them out of the air. You might say she has a gift for coordination.

Curtain call for Nina Ananiashvili's farewell performance with ABT.

Photo: Gene Schiavone

At the opposite end of the spectrum, a pair of Giselles I saw, differently tempered because danced with two different partners, were luminous. With Marcelo Gomes, Ananiashvili matched the power of his stage presence; with Jose Manuel Carreño, she echoed his more understated, yet emotion-filled approach, effortlessly launching shape after beautiful shape into the air, then letting them dissolve into the flow of the dancing.

Moving through the trajectory of Giselle's story, Ananiashvili gives us both the shyness and blitheness of an innocent girl utterly in love; the suddenly distorted landscape of a woman literally broken-hearted by that lover's betrayal; then, beyond the grave, a mature sorrow for his plight, his anguish as well as an enduring devotion that saves his life. As the story unfolds, we come to know a remarkable person who remains nakedly true to herself from beginning to end, one of those rare human beings wrapped in a cloak of tenderness.

Ananiashvili's Mad Scene--the result, no doubt, of years of thought, experiment, and minor but telling adjustments--is an example of how the wholeness of her performances is now invariably extraordinary, every detail of movement and feeling perfectly accounted for, anything extraneous firmly excised.

In both Giselles, she gave us immaculate dancing that was nevertheless softened and full of grace. Yes, her grands jetés cleave the air, but they seem as downy as rose petals. In her high-speed whirling initiation into the tribe of wilis, her legs swathed in the layers of her tulle skirt, her foot barely grazes the floor as she turns herself into a gossamer cloud caught in whirlpool of wind. Her grace has a spiritual dimension, too, that makes her Giselle real, loveable, and tragic, and it is this quality--of the soul perpetually infusing the body--that make our hearts hers.

Ananiashvili's many fans may wonder why this much beloved ballerina would withdraw from the big time when her technique was still up to the challenges of such works and her artistic powers were at their height. Reasons for such major decisions depend greatly on instinct--what your heart or gut is telling you. But Ananiashvili is practical enough to placate her audience (and, perhaps, herself) with a handful of practical arguments in favor of bowing out: to support her husband, Grigol Vashadze, Georgia's Foreign Minister, who is pursuing a burgeoning political career, just as he has helped her in the last two decades of her career; to spend more time with their young daughter, Helene; to further the development of the State Ballet of Georgia, based in her home town of Tbilisi, which she was specifically brought in to head in 2004; and because she knew--and admitted to herself, as so many dancers are unable to--that the body's abilities inevitably fade with age. Any one of these reasons would be persuasive.

There's no denying that a significant part of Ananiashvili's appeal is her sheer physical loveliness. Her face, with its creamy skin, dark hair, and heavily browed, soulful dark eyes, has the cast of a Spanish Madonna. Underneath that look is an instinctive empathy for the characters on stage around her. Her long, exquisitely proportioned body seems destined for classical dancing. Her promise of beauty and the perfect poise of her body--a natural harmony--is evident even in snapshots of her as a child. Complementing these attributes is a melancholy frequently underlying even her most vivacious roles, where her smile is infectious, even teasingly flirtatious, yet her eyes suggest that she knows that everything in life is evanescent.

From her first engagement with an American company (a guest stint with the New York City Ballet in 1988), we've seen how smart she is, how open to ideas about dancing that are radically different from the Russian ones in which she was scrupulously bred. She was accompanied in the venture by her celebrated Bolshoi colleague Andris Liepa, who continued to do everything in the Russian way familiar to him, while Ananiashvili tried to absorb Balanchine's way.

In the course of her sixteen years at ABT, we've watched the harmony and flow of her dancing in the lyrical vein become more and more beautiful and natural, like the motion of a nymph--a naiad perhaps. The steely aspect of her personality has served her in good stead--both in her dancing, when virtuoso passages require it, and offstage in shaping her career and leading the State Ballet of Georgia, essentially a pleasant regional company that the government is eager to upgrade. She is also blessed with a sense of humor, which Alexei Ratmansky caught in Waltz Masquerade, the pièce d'occasion he created for her to perform at ABT'S opening night gala. It might have been called "The Diva and Her Devotees."

Diane Solway, interviewing Ananiashvili in W Magazine, asked the ballerina what she'd be doing after her farewell performance with ABT. The answer: "Crying." Her tears were not the only ones shed on the occasion.

© 2009 Tobi Tobias

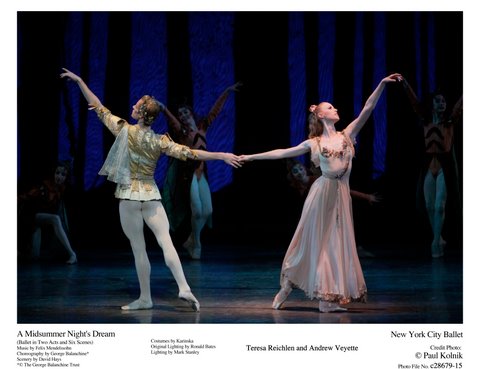

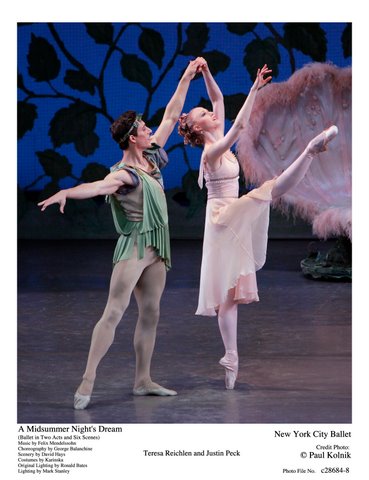

New York City Ballet: George Balanchine's A Midsummer Night's Dream / David H. Koch Theater, NYC / June 16 -21, 2009

George Balanchine's A Midsummer Night's Dream, screening of the 1967 film / Baryshnikov Arts Center, NYC / May 26, 2009

George Balanchine's A Midsummer Night's Dream, created for the New York City Ballet in 1962--with co-collaborators William Shakespeare (libretto) and Felix Mendelssohn (music)--is a perennial enchantment.

Some observers will dismiss it as too "pink" (a favorite Barbara Karinska color for her costumes), but it covers a wide spectrum of jealousy, greed, questionable uses of power, sexual attraction between woman and ass, foolishness, stupidity, and murderous rage (albeit most of these tempered by their comic aspect) before arriving at its magically happy resolution.

You know the story; you read it at school. If you've forgotten it, treat yourself to a refresher course. The delightful text is no further away than your computer (http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/8609). Though Balanchine is remembered as saying he was primarily inspired by the music, he renders the narrative deftly. At the age of eight, apparently, he played one of the tiny creatures of the air that inhabit the story in a St. Petersburg production, and City Ballet alum claim he remembered and would recite excerpts from the text in Russian.

From the company's week of Midsummer performances this season, at the David H. Koch Theater, I chose the cast that featured Teresa Reichlen as Titania, Queen of the Fairies. Reichlen's career is still relatively young, but she's been a winner from the start. It's not just the impeccable dancing accentuating her very long limbs and perfect line I admire, but her courage as well. She tackles prominent assignments with authority and, it seems, the expectation of pleasure.

As Titania she has decided upon a combination of empathy with her fellow characters--child, adult, and--yes--donkey. She is alert to their needs without ever relinquishing the characteristics of queenliness. For example, she allows the laborer magically transmuted into an ass his yen for dewy grass to nibble on but never loses her faith that--coaxed onto his hind legs--he may make a suitably elegant partner in a pas de deux.

When, after much imperious argument, she finally cedes possession of the changeling child in her retinue to Oberon, her kingly counterpart, it's simply because he desires it so intensely (even though his methods of acquiring it include attempted kidnapping). Everything about Reichlen's Titania is warm as well as aristocratic.

Reichlen can't yet lay claim to the sudden plunges from the vertical that made Suzanne Farrell's celebrated interpretation so sensuous and exciting, but perhaps that is never to be.

The male stars in this performance, Gonzalo Garcia as Oberon and Troy Schumacher as Puck, were adequate but not memorable. The most striking performance was given by Janie Taylor, beautifully partnered by Tyler Angle, as the couple in the wedding divertissement who embody perfect love. This season has marked Taylor's return to the repertory after prolonged absences. A fragile, often thrillingly wild dancer, Taylor is one of those performers whose soul seems to dance through her. The audience recognized this in a instant, with hold-your-breath silence and then tempestuous applause. She's one of a very rare breed and deserves all the cherishing that can be given her.

A bevy of children (pupils of the company-affiliated School of American Ballet), playing the chorus of winged insects or fairies threaded through the piece, made it heartening to see that today--compared to yesteryear when I first saw the ballet--the students have acquired a fleetness and clarity unknown to their predecessors and at an earlier age. (This means that younger, thus smaller, children can be used, offering a more piquant contrast with the adults). Balanchine, of course, had a way with dancing children that has never been equaled in the States. He assigned each level of youngsters steps they could do effectively, with precision and verve, without losing their natural charm.

Transparency note, should one be needed: As a student at the School of American Ballet, my daughter danced for a few seasons in this chorus of airy sprites. She was young enough to need an adult escort to and from the theater, and it was a long, dreary wait between commutes, since the kids figure in the choreography from beginning to end. But the music was piped into the chaperones' holding pen during the performance, and I'd often find my way (i.e., sneak into) the back of the auditorium just in time to watch the exquisite Act II pas de deux. Danced, appropriately, by a couple that has no role in the story, it is an abstraction of love's deepest feelings and perfectly beautiful.

Suzanne Farrell as Titania

Courtesy NYCB Archives

A few weeks before the City Ballet finished its spring season with seven performances of Midsummer, the Baryshnikov Arts Center offered a single screening of the 1967 film version of the ballet, directed by Dan Eriksen and the choreographer. Whatever its flaws, and they are considerable, it reveals the qualities that made its leading dancers legendary. The young Suzanne Farrell reveals miracles of supple and impetuous motion as Titania. As Oberon, Edward Villella deploys his mercurial footwork, mating ferocious speed with rock-steady power. He originated the role, and his only subsequent rival since has been Helgi Tomasson, rendering the choreography in the fleet style that made him look airborne. Arthur Mitchell, as Puck (he, too, created his role) is simply not replaceable--a gleaming-skinned figure with a handsome, knowing face, who is clearly a born trickster.

The cast also includes the already dazzling Patricia McBride, Nicholas Magallanes, a soulful Mimi Paul, Jacques d'Amboise, and Allegra Kent. Veteran City Ballet followers will also enjoy singling out, amid the corps, dancers they recall fondly from the company's mid-twentieth-century blossoming.

In many ways the production is a natural result of the era's prevailing film conventions, which were then so commonplace as to be unnoticeable. But in no way is it equal to the live performances the City Ballet has given us over the years and what video has accomplished in the last half century to transfer ballet more authentically to the screen.

The worst aspect of the film is its scenery. It's not merely a case of the patently fake asking us to take it for reality but also a question of its hampering the choreography. The combination undermines the ballet in both its woodland-animated-by-spirits and its aristocratic locales. In the forest, the landscape has the falsity of a plaster and plastic background for a model railroad or a Playmobil rainforest. What's more, the pseudo-Mother Nature foliage constantly obscures the view and threatens the dancers with vines to trip over, trees and bushes to block their path. One of the basic requirements of Balanchine dancing is clear space.

The second act takes us to Theseus's court to celebrate three weddings, those of the Duke of Athens himself with the Amazon huntress Hippolyta (an odd couple, perhaps) and the two pairs of plebeian lovers, whose complicated, shifting interrelationships ("What fools these mortals be!") are finally straightened out--not without some early errors--by Puck at Oberon's command, using doses of a rare rose pollen. The royal residence and grounds, with their imposing staircase and multi-tiered fountain, look like a Reno rendition of Louis XIV's palatial concept of house and garden.

At the finale, back in the forest, Titania and Oberon are reconciled; she relinquishes the changeling child in her retinue that Oberon coveted to the point of their quarreling vehemently over it. But they are, pointedly, not included in the marriage rites (perhaps, as king and queen of the fairies they are already "married,") and they part, moving off in opposite directions, though slightly turned to each other, each gently waving a hand in an amicable temporary farewell. Balanchine liked to explain (perhaps tongue in cheek) that they're fairy folk, a breed that doesn't engage in carnal intimacies.

Inevitably, the film makes alterations to the choreography that are disconcerting, at times downright confusing when it comes to keeping the plot straight, especially concerning the quartet of middleclass lovers. At other times, there are effects that are plain silly, such as the "magical" appearances of characters out of thin air. Balanchine makes magic with his imagination that is far more potent than elementary camera tricks.

The camera does its worthiest work with close-ups. While the ravishing dewy beauty of the sleeping Titania is pure Hollywood, where Balanchine did some time in the 1930s and '40s, it's a blessing because you'd never be close enough to see it in the theater.

Now for the really bad news. Just before attending the single public showing of the film at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, I viewed it on my computer, using a screener provided by the celebrated Parisian archival institution, the Cinémathèque Française. It was wonderfully clear. The mechanics of the BAC showing, also using a Cinémathèque print, were simply not of professional caliber. Throughout, the image was migraine-inducing--severely blurred, accompanied by deafening sound. Nobody tried to fix this. Then, at the brief live Q & A that followed the film, the microphones worked only sporadically--an apt coda to the general malfunctioning of the event. Suzanne Farrell, straightforward and charming, and the deft interlocutor, the dance writer Robert Greskovic, coped with the situation like troupers.

© 2009 Tobi Tobias

School of American Ballet Annual Workshop Performances 2009 / Peter Jay Sharp Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / June 1 (matinee and evening); June 3 (evening)

"But first a school," Balanchine is said to have replied to Lincoln Kirstein, when the later was urging him to be the lynchpin in forming a ballet company in the States, intuiting that this choreographer--a genius without a job and in poor health to boot--would change the face of the art. The result of that exchange is evident today not only in the prowess of the New York City Ballet, which recruits the majority of its dancers from the advanced divisions of the school, but, tellingly, in the annual three-performance run of the School of American Ballet Workshop at Lincoln Center's Peter Jay Sharp Theater. This year, Workshop offered an all-Balanchine program to celebrate SAB's 75th anniversary.

Serenade. Choreography by George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The program consisted of Serenade (the first ballet Balanchine created in America); the "Ballabile des Enfants" from Harlequinade (to show off the astonishing acumen of the juniors in the school, mostly in the 9-12 range, though some looked no more than six), and Stars and Stripes (to activate our patriotism? to show the delicious corniness and bravado of American culture, which delighted and amused the choreographer? to give roles to large flocks of young women and men who many not yet shine as incipient stars but collectively form an impressive ensemble? to provide a rousing closer?).

To me, the program seemed skimpy--too short, for one thing and too much a one-choreographer-show when for decades past the students were shown as well in work by Petipa, Ivanov, Fokine, or Bournonville (to say nothing of Jerome Robbins), which added other significant dimensions to their training. A new work was often commissioned for the program, too. Granted, this was sometimes a mixed blessing, but on other occasions the assignment was a challenge and an encouragement for a emerging choreographer--like, for instance, Christopher Wheeldon.

The program as a whole demonstrated the uncanny skill developed by SAB pupils who stay the course. Serenade, staged by Suki Schorer, a former City Ballet principal now celebrated for her Balanchine productions, was impeccably rendered, with the small nuances Schorer notices and remembers giving the faithful reproduction life and warmth. The choreography itself, though you may have seen it a hundred times, invariably looks new, fresh, a miracle of immediacy. In the matinee and evening performances (which offered cast changes) that I saw on May 30, I especially admired Shoshanna Rosenfield, Lauren Lovette, and Adam Chaviz, who still looks like a stripling but already dances with unmistakable poise and grace.

Garielle Whittle, an SAB and City Ballet alum, supervised the charming "Ballabile des Enfants," representing familiar commedia dell'arte characters. Here, the littlest dancers, particularly, were like tiny faceted jewels, glittering as they moved with uncannily sharp footwork. The "Whispering Dance," as it's called, for four boy-girl couples at the mature end of the Children's Division, made elegant Scaramouches, chicly costumed in jet black with white-plumed headgear. This segment, though, seems to have lost some of the mysterious atmosphere that once enveloped it--that aura of children just becoming aware of the adult world's secrets. Or did I just imagine it existed years ago? I think not.

Susan Pilarre, who, once upon a time, when she was an SAB pupil, played children's roles with the City Ballet, staged Stars and Stripes, distinguished for two of its four sections--first for the all-male "Thunder and Gladiator," in which a regiment parades its feistiness in ever-changing geometrical patterns and jumps festooned with beats. They're like a bunch of toy soldiers and irresistible even to a confirmed pacifist, who couldn't possibly imagine any one of them coming home in a body bag.

Angelica Generosa in Stars and Stripes

Choreography by George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Equally engaging, in the "Liberty Bel[" duet that caps the ballet, was Angelica Generosa, who is as sweet and sassy as they come, gently funny (as she should be here), with all the appearance of enjoying every minute--in other words, a born soubrette. She learned this role in merely a week, to replace an injured classmate, Ashly Issacs. Meanwhile Isaacs has been honored with one of SAB's prestigious Mae L. Wein Awards, which predicts a successful future.

Serenade

Choreography by George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust

Photo: Paul Kolnik

© 2009 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary