Seeing Things: April 2008 Archives

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on April 29, 2008.

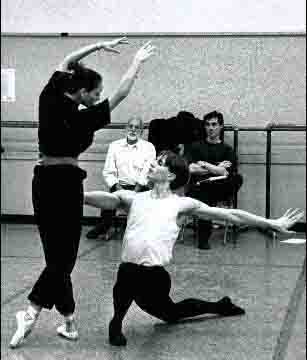

Jerome Robbins, second from the left, observes a New York City Ballet rehearsal in New York in this undated handout photo. Starting April 28, 2008, at Lincoln Center's New York State Theater, the New York City Ballet begins a season-long homage to the late Jerome Robbins on the 90th anniversary of his birth. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

April 29 (Bloomberg) -- The ringmaster of a mock circus directs 48 little girls from the School of American Ballet who finally spell out JR, the initials of the performance's honoree. Tonight at Lincoln Center's New York State Theater, the New York City Ballet begins a season-long homage to the late Jerome Robbins on the 90th anniversary of his birth. It's an unabashedly show-bizzy gesture for a choreographer who was, in truth, better suited to the Broadway stage than to ballet's.

Think of ``West Side Story,'' the reimagining of the Romeo and Juliet legend as a timely saga of teenage street-gang conflict and young love; the lusty ``Fiddler on the Roof'' and the sheer enchantment of the ``Small House of Uncle Thomas'' ballet from ``The King and I,'' each created for Broadway.

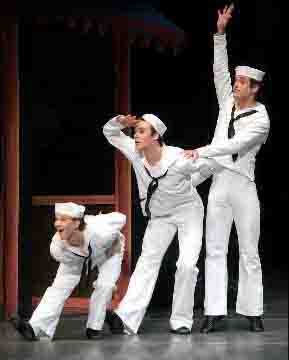

Robbins's choreographic debut in the ballet realm, ``Fancy Free,'' (made for American Ballet Theatre), following the escapades of three sailors out on the town, was a dazzling hit and remains a repertory favorite. Like all of Robbins's choreography, it's set down to the last fingernail -- while creating an illusion of naturalness that Robbins never achieved again.

Dancers, from left, Daniel Ulbricht, Tyler Angle and Benjamin Millepied perform in New York City Ballet production "Fancy Free," choreographed by Jerome Robbins, in New York on Feb. 11, 2006. On the evening of April 28, 2008, at Lincoln Center's New York State Theater, the New York City Ballet begins a season-long homage to the late Jerome Robbins on the 90th anniversary of his birth. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

He could be a demon in the rehearsal studio -- terrible tales abound -- but his implacable demands served vaulting creative visions he felt were just beyond his grasp. One must add, to his credit, that when he decided to commit himself, long-term, to a classical company, he chose to work in the shadow of George Balanchine at the New York City Ballet. In any other company, he would easily have been top guy.

Package Deals

The City Ballet's nine-week season will offer 33 Robbins ballets. As is the troupe's current custom, the repertory is arranged in package deals -- groups of ballets that can only be seen as a unit. The tactic is bound to squelch the enthusiasm of dance fans who attend regularly and appeal, instead, to a general audience reassured by group labels like ``All American Fare'' and ``Generation Next.''

The Robbins packages being offered in the first two weeks contain only two ballets I'd recommend unreservedly: ``Les Noces'' (better than anyone else's version but Bronislava Nijinska's) and ``Fancy Free.'' Matters improve later with ``Afternoon of a Faun,'' ``The Cage'' and an all-Chopin program containing ``Dances at a Gathering,'' ``Other Dances'' and the still hilarious ``The Concert.''

Topping the list of ballets you'd be happier skipping is the endless, slow-motion, pseudo-philosophical ``Watermill.'' Still, it's bound to sell well since the company has been astute enough to call Nikolaj Hubbe out of recent retirement to play the lead. Hubbe, with his maverick imagination, and the creator of the role, Edward Villella, all rugged intensity, are the only two I can imagine making something riveting of such navel gazing.

Of course, all of it -- the splendid, the so-so and the experiments that never worked -- deserve their moment in the spotlight on this occasion, if only as an indication of the scope and evolution of Robbins's work.

At Lincoln Center through Jun. 29. Information: +1-212-721-6500; http://www.nycballet.com.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

The dress on my back, the cloth on my dining table--unique, beautiful, old, and absurdly cheap. "Where'dja get it?" the appreciative and envious exclaimed. Gerry's, of course.

I came across Gerry and his goods plowing my way home through a street fair devoted, as these events are nowadays, to the peddling of tube socks, junky electronic gizmos, bras and bikinis ostensibly name-branded, off-brand sheets, discontinued makeup and food as likely to kill as to nourish you.

It was high summer and the weather was stupefyingly hot and humid; the wares, depressingly tacky. Suddenly I spied, manifesting itself like an oasis-in the-desert mirage, a long rickety table heaped with fabric that all but spelled out "vintage" in neon light. I spent the next three hours there, pawing through the mound, finding things, among a crowd of enthusiasts. From them I learned that the scruffy youngish man in charge was called Gerry and that he and his offerings appeared irregularly--this was part of the mystique--at such fairs.

Every Sunday morning in the next month, I went out hunting for the elusive Gerry's "show" (as I found he called it), sometimes successfully, sometimes not. Eventually, I got on a semi-secret phone-alert list that made me privy to the dates and venues of upcoming shows, relayed by a disembodied young female voice. From then on, on the next designated date, fifteen minutes before the appointed hour, I would join the faithful gathered at the indicated Upper West Side locale, waiting in a state of anticipation comparable to that of a very young child on the morning of his birthday. I was rarely disappointed.

Here's how the maverick operation worked: From the back of a roomy SUV, Gerry, the sole proprietor and impresario of the enterprise, drew a large collapsed trestle table and set it up in the street. Then, with the help of a few volunteers from the eager crowd, he removed dozens of giant trash-bagged bundles from his vehicle and piled them high on the table. They formed a veritable mountain that loomed high over the heads of the participants. Only after the last bag had been stacked did Gerry give the signal that his low-end boutique was open for business. We, his clients, then precipitously threw ourselves upon the bags, ripped them open, and began rooting through the loot.

Just before the opening gun, Gerry had thrust at each prospective shopper a large plastic bag of an institutional royal-blue hue. A horizontal oval cut out near the top of the bag created a handhold. In these circumstances, however, you grabbed your bag, slung it over your arm, and pushed it way up to the elbow so you'd have both hands free. Digging for treasure chez Gerry was definitely a two-handed job.

What, exactly, was in the mountain? Delicate christening gowns, an amazing number of them. Spunky daytime dresses that women wore before jeans were declared to be the uniform for ordinary life. Cocktail dresses, ball gowns, and tuxedo jackets (which today's women know look fabulous over their uniform of white t-shirt and faded Levis). Tablecloths galore, sometimes with matching napkins, in every size imaginable--from bridge-table squares to banquet-length double damask. Towels of every ilk, including those divine European linen ones with the owner's initials embroidered at a corner in red cross-stitching. Yesteryear's baby clothes and kidwear, a study of which would make a fertile dissertation subject for a budding sociologist. Undergarments that included pantalettes from the Victorian era and peach-colored corsets your grandmother might have worn (both find rakish uses today). Hats, shoes, and gloves (occasionally the white kid "Opera length" kind that reaches from impossibly slender fingers to above the elbow). Shards of ravishing embroidery, beading, or lace--all sheared from their original location but considered by some unknown salvager--bless her or him!--too wonderful to jettison.

The basic endowments for your initial search through this merchandise were a keen eye, speed, and ferocity of purpose. The idea was to stow away in your increasingly heavy blue bag anything at all that spoke to your imagination. The elimination process would come later.

Everything was "used," of course. And nearly all of it was old, some of it, as I've indicated, seriously old. Rips, frayed edges, not quite obliterated coffee or wine stains, and other signs of age often made the garment--or linen item--somehow more precious, the way wrinkles give a mature face character. Occasionally I bought examples of meticulous mending, an art that has vanished in today's throwaway culture. The love, labor, and deftness with which a hole in an antique linen sheet had been repaired never failed to pierce my heart.

In the world of Gerry's, age was a plus. His customers seemed to agree that clothes were better "back then," whether they thought "then" was the Sixties and Seventies or the Thirties and Forties. (I admit to the insufferable snobbery of believing that fashion--in a classical sense that includes wearabililty and grace--ended in the Forties.) Clothes were certainly better made back in the day.

Among my favorite acquisitions were black and midnight-blue dresses from the Twenties through the Forties that became mainstays of my "look," and then, skipping ahead to the extravagances of the Seventies, a killer-flamenco dress--several pounds of flirtatiously ruffled black lace that I never wore but took out to revel in at least twice a year. My oddest find from the stylish past? Two pairs of men's white suede summer oxfords with those characteristic perforations--very Great Gatsby. They were almost brand new, and they actually fit.

A small percentage of Gerry's offerings were actually theatrical costumes. Another small percentage--one I cherished--comprised extremely old items. A wisp of a white finely embroidered handkerchief, at least two centuries old, from the look of it--you could, as they say, read a love letter through it and time had lent it a faint sepia cast--had managed not to give up the ghost in the ravages we perpetrated on the dense, twisted pileup of cloth. I rescued it, washed and ironed it with scrupulous care, and took it to Renée, my dear friend in Paris. Utterly in sympathy with it, she had it framed and hung it in her bedroom, in the company of leather-bound books equally antique.

Where on earth did Gerry get his stuff? Of course we were curious, but in vain. He was cagily vague on this subject, even if questioned directly. "Oh, here and there." Costume-museum cast-offs was one of the most shocking and unlikely sources he'd mention when pressed further, though the nature of his more compelling holdings hinted that he was telling the truth.

Gerry's clientele was largely female and divided between two subsets: those who dressed with debonair éclat, looking to add to their holdings, and those--collagists and quilters among them--who converted their acquisitions radically, giving them a completely new identity.

Regular Gerry's customers got to know each other and, while frenetically mining the fabric mountain for items that would suit them, always took the time to find things for their sisters. "Who's into lace?" one might call from one side of the heap, holding high a gossamer white cloud, then pitching it across the towering stack toward the ebullient voice that replied. Or, "Mirelle," uttered in a shriek of pleasure, "you're gonna love this!" and the said Mirelle's arm would shoot up--palm cupped, fingers splayed--to catch the soft missile being flung in her direction.

The only motionless figure I ever saw in this crowd was Sienna, a ravishing child about seven years old, with red-gold hair falling to her shoulder blades and curling in pre-Raphaelite tendrils around her pale face. She was exquisitely poised and unusually silent. By contrast, Estella, the middle-aged grandmother in charge of her, was an earthy, loquacious type with gypsy looks. Physically and temperamentally, they seemed entirely unrelated. I guessed that Estella was buying for a modest private resale enterprise, perhaps to put bread into the child's mouth.

At one Gerry's session, I insisted upon buying Sienna a winter coat that the gods had obviously designed, a half-century back, with just this eerily lovely child in mind. Executed in black poodle-fur, with a neat little collar and a double row of buttons parading primly down the front, it was cut to hug a slender torso, then flare out at skirt level as if whipped suddenly by a November gust. Perfect in its propriety, imaginative in its fabric, meticulous in its tailoring, it was fit for the heroine of Frances Hodgson Burnett's A Little Princess in her days of good fortune.

To return to the Gerry's ritual: Once you felt you had fully inspected the hoard of stock (this took at least an hour and a half), the next step in the selection process was to dump the contents of your blue bag out onto the adjacent sidewalk and inspect it, piece by piece, to see which items you really must have or die.

While you did this, another client might hover nearby, politely if sometimes pointedly waiting until you, the original claimant, were done considering a good percentage of your items. The observer wouldn't touch a thing until the moment seemed right to inquire, "Can I look at your discards?"

A cooperative client (and most were) would then sort her haul into three distinct piles that she indicated were, as far as her own taste and needs went, Keeper, Maybe, and Forget It. The waiting observer was entitled to examine--and stash in her own blue bag--anything in the Forget It pile. By an unspoken courtesy, she would shoulder the responsibility of returning the items she didn't want back onto the still-looming mountain on the trestle table--unless yet another hopeful connoisseur of discards stood waiting (body motionless, avid eyes scanning) behind her.

Of course these rules, which evolved logically from the needs of the situation, were written nowhere and spoken about only when a newcomer to the process, at a loss as to how the system worked, asked for initiation. The conduct of the whole affair was a convincing argument for letting women run a nation's government.

Decisions about household linen--whether for table, bed, or bath--can be made by eye and feel alone. Sheer guesswork prevails in choosing articles of clothing you plan to present to your near and dear. But garments you may allow to enter your own wardrobe must be tried on, though an intuitive few can look at a lavish night-life costume or a sober pencil-slim skirt and know if it will fit them flatteringly. Most of Gerry's clients needed to try on the clothes that had snagged their attention and so created dressing rooms of an invisible architecture on the sidewalk, close to the building line, as if having a bricks-and-mortar structure only inches away from your all but naked body somehow preserved your modesty.

A typical Gerry's customer, you see, would arrive at the scene clad in the usual flea market costume--jeans or shorts that had seen far better times, a ratty t-shirt, and a banana pouch to hold the bare necessities (money--needless to say, Gerry accepted only cash; a bank card for getting more money; a Metro card; a piece of i.d.; a comb). The savviest among us learned to skip regulation underwear--bra and bikini pants, an outfit the New York police consider adequate for the beach but insufficient coverage smack in the middle of town--and substitute some sort of cat-suit arrangement cut back to biker-shorts height on the legs and singlet sleevelessness on top.

No mirrors were available, not even the usual flea market looking-glass, shakily angled against an unreliable support, so cheap it reflected you with fun-house distortion. With luck, shop windows, if a shop's interior was dark enough, would provide a murky likeness.

Other than that, we used our own finely honed instincts about how a garment felt on our body and our sister shoppers' opinions. "What do you think?" we'd ask, presenting ourselves dead-on to the friend we had brought to the scene or an acquaintance we had made on the spot, then revolving in slow motion to be inspected from various perspectives.

Nearly always, the negative responses combined truth with tact. The positive ones, in their enthusiasm, were less decorous. "It's totally you. You'd be insane not to take it." Or, "If you don't take it, I will--and cut it up into a dozen pieces and make pillows." The dismantling threat often convinced the doubtful model of the garment that it was her moral duty to extend its life intact. Pillows could come later, after she had worn it to death in its original form.

Once a client had winnowed her holdings to the pieces she really wanted, she stuffed them back into her blue bag, deposited any further discards that hadn't been gobbled up back on the heap, and placed herself at the end of a line of people that led up to Gerry.

The line could be long, but the pricing system had the swift efficiency of a guillotine. One by one, you'd remove the items from your bag and Gerry would tersely quote a price. "Three bucks." "One." "Five." "Ten." On each item, the shopper was allowed only one of two responses--yes or no. Haggling was forbidden. If you answered yes, Gerry scribbled the number down in a notebook that had seen much service. If your response was no, Gerry took the item and tossed it back on the heap. Once everything in your bag had been priced, Gerry added up the numbers in his notebook, announced the result, and you forked over that many dollars. The entire process clocked in at under three minutes.

You then scooped your yeses back into your blue plastic sack--or, if you were a Big Buyer, like Estella, into one of those ubiquitous plaid zippered shopping bags you'd presciently brought along--and moved on to the nearest Starbucks for a restorative dose of caffeine.

Needless to say, once the madness of the moment had subsided, some of our purchases would turn out to have been mistakes. But, as my frequent companion on these forays--Andrea the quiltmaker, author, swimmer, and Ph.D. candidate--points out, sighing with nostalgia, the entertainment value of The Gerry Experience was reward enough for the lavish investment of time and the ridiculously modest investment of cash.

Nostalgia? Yes, after several madcap years, Gerry's enterprise folded. Not even his most persistent regulars could trace the man. Having created his unique delight for a time, he was gone--like Mary Poppins. Dozens of us fans were left broken-hearted--and with Sunday mornings once again at our disposal. Finally we might have time to clean our closets.

© 2008 Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on April 10, 2008.

April 10 (Bloomberg) -- Ethereal spirits of the wood, dream visions of love, luscious adulterers and a tragically expiring swan -- the Kirov Ballet can offer them all in a one-man show.

The company's second program -- in an engagement that runs through April 20 at New York's City Center -- offered four key ballets from the early 20th century by Michel Fokine. The choreographer was a neo-Romantic reformer who countered the diamantine brilliance of the 19th-century master Marius Petipa with a pearly glow.

Members of the Kirov Ballet perform Mikhail Fokine's "Chopiniana" at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, on Jan. 10, 2005. Kirov Ballet will be performing at New York's City Center through April 20, 2008. Source: Mariinsky Theatre via Bloomberg News

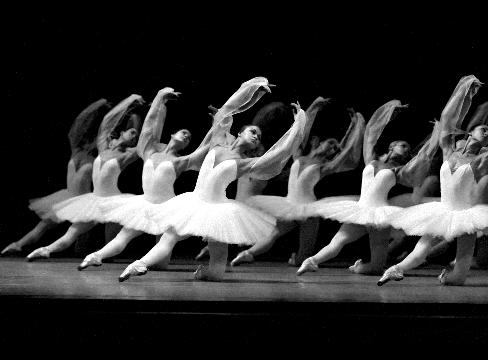

``Chopiniana'' (aka ``Les Sylphides'') depicts a musing poet's encounter with a flock of gauzy apparitions in a moonlit glade. It is the loveliest of the Kirov's presentations so far. The female corps de ballet and three soloists seemed to be buoyed into the air on their own breath or wafted side to side by an errant breeze. Their feet touched the ground as softly as cats' paws. The prevalent mood was not spooky, as in most renderings, but one of gentle delight.

In the ballet's only male role, Anton Korsakov offered beautifully measured dancing yet couldn't project the inspiration the poet is presumably feeling. Ekaterina Osmolkina, in the variation of surging cross-stage leaps and in the pas de deux, was perfection.

Commanding Technique

``Le Spectre de la Rose'' showcases a male virtuoso who embodies the spirit of a rose in full bloom, awakening a virginal young woman to love's sensual pleasures. The role was made for Vaslav Nijinsky; the only dancer I've ever seen get the upper hand of its bravura feats (and petal-garnished costume) was the Kirov-trained Mikhail Baryshnikov. Though the young Leonid Sarafanov commands the technique for the assignment, not one of the three dancers I saw captured the tendril quality of the wreathing arms and the figure's creaturely nature.

Fokine created ``The Dying Swan'' for Anna Pavlova, who made the brief solo her signature piece. Today, depending on the performer, the avian death throes can look hackneyed or convey something basic and poignant about the human condition.

Alternating in the role, both Uliana Lopatkina and Diana Vishneva did creditable jobs. All fragility and jagged angles that expressed pain, Lopatkina was essentially pictorial. Working from the inside out, Vishneva was the more convincing. After witnessing her visceral interpretation, it should be hard for the viewer to remain indifferent to the corpse of even of the most insignificant sparrow lying on the pavement.

Favorite Wife

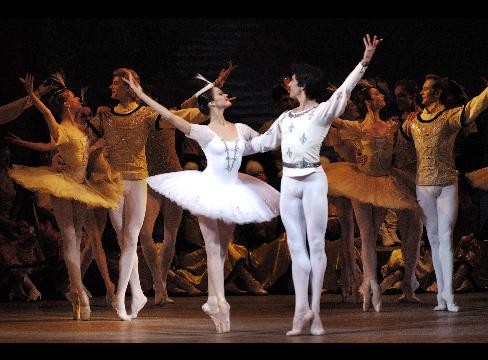

Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, on Sept. 15, 2006. Kirov Ballet will be performing at New York's City Center through April 20, 2008. Source: Mariinsky Theatre via Bloomberg News

Vishneva and Lopatkina alternated again as the Shah's favorite wife in ``Scheherazade,'' an over-the-top extravaganza that mates sex with danger in an exotic locale. Lopatkina attempted a Stanislavskian job, at first canoodling with the Shah like a sex kitten, yet intermittently revealing her discontent with her master. Vishneva threw herself into the melodramatic proceedings body and soul, especially in the long duet with her underclass lover, the Golden Slave, which seems to be all coital undulating. Though the prolonged orgy inevitably grows tedious, the fabulous Leon Bakst-derived costumes always gave the enthusiastic audience something terrific to ogle.

Following the Fokine showings, the Kirov returned to its display of the Petipa tradition -- unfortunately offering three flashy pas de deux in succession. The tactic may wow the crowd, but it undermines the art. Still, Victoria Tereshkina made all tawdriness vanish with her clear, bold, unaffected dancing; Balanchine would have loved her. Another consolation was the presence of Ekaterina Kondaurova, whose dancing, like her appearance -- very tall, very slender, her aristocratic face capped with gleaming, copper-colored hair -- is the epitome of elegance and sophistication.

Through April 20 at City Center, 131 W. 55th St. Information: +1-212-581-1212; http://www.nycitycenter.org.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on April 4, 2008.

April 4 (Bloomberg) -- The Kirov Ballet's three-week run at New York's City Center opened Tuesday with wall-to-wall choreography by Marius Petipa, the grandest master of 19th- century ballet. That makes sense. The company is widely revered in America as the font of such dancing, having given the world Pavlova, Nijinsky, Nureyev, Makarova and Baryshnikov.

Members of the Kirov Ballet perform at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, on March 30, 2005. Kirov Ballet will be performing at New York's City Center through April 20, 2008. Source: Mariinsky Theatre via Bloomberg News

It wasn't one of Petipa's multi-act works on view this week, though, but rather the showiest segments from several, as if the presenters feared losing the attention of their audience.

The bill consisted of the festive third act of ``Raymonda,'' (think medieval Hungary as conceived by a tsarist imagination); the Grand Pas from ``Paquita,'' (which offers a ballerina, her cavalier and a bevy of soloists every chance to display their technical audacity in both allegro and legato modes) and the sublime ``Kingdom of Shadows'' scene from ``La Bayadere,'' where the scrupulously schooled female corps de ballet becomes a star in its own right.

Members of the Kirov Ballet perform at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, in this undated handout photo. Kirov Ballet will be performing at New York's City Center through April 20, 2008. Source: Mariinsky Theatre via Bloomberg News

The season features Uliana Lopatkina, in whom nearly every human quality is subjugated to forge an icon of classical ballet. Lopatkina is eerily slender, with muscles so fine-honed they mask her steely control. Stretching her long limbs in arabesque, she etches a line from fingertips to toes that is impeccably graceful. The slow-streaming lyricism of her movement is echoed in the moods that flicker across her face, usually tender, somewhat melancholy and aloof. Whatever she does is a marvel of exquisitely calculated delicacy.

Down to Earth

Viewers who find this type too rarefied may prefer the other ranking ballerina, Diana Vishneva, more compactly built and more down to earth. Vishneva can do everything -- every step and every style -- with vibrant aplomb. When she whipped off the 32 fouette turns in ``Paquita,'' punctuating them neatly with doubles, she made this old challenge look like a game she was confident of winning. From the heady dramatic works she performs in annual stints with American Ballet Theatre to the jazzy off-kilter work of Balanchine's ``Rubies,'' she's on the mark.

The Kirov's men are conspicuously less distinguished, apart from the wunderkind Leonid Sarafanov. Small and slight like Peter Pan, he projects a ferocious desire to surpass even his present astonishing virtuosity.

His spectacular feats, flawlessly brought off, seem to be fueled by well-nigh manic energy. His leaps are high and wide, his whiz-bang turns have perfect control, his landings are as sure-footed as a mountain goat's. Andrian Fadeev, another of the young men the company is bringing forward, doesn't yet have the technical security to match his personal charm.

Meticulous Execution

In general, the company dances as if to the manner born, giving first allegiance to meticulous execution. Even the folk- tinged segments in ``Raymonda'' sacrifice their rightful lustiness to the aristocratic demeanor. It comes as no surprise, then, that the performances aren't emotionally persuasive. No doubt this will loosen up in the course of the season, allowing for some of the spontaneity that is an essential part of dancing.

Starting this weekend, the Kirov will offer programs dedicated to Michel Fokine, William Forsythe and George Balanchine.

Through April 20 at City Center, 131 W. 55th St. Information: +1-212-581-1212; http://www.nycitycenter.org.

More Dance

In addition to the balance of the Kirov season, the most noteworthy dance programs on the horizon are:

Ballet Tech's ManDance Project (Joyce Theater, April 9-20), for which Eliot Feld has choreographed a new solo for Fang-yi Sheu, the pre-eminent Graham dancer to appear in decades;

Edward Villella's Miami City Ballet (Long Island's Tilles Center, April 25 and 26; Princeton's McCarter Theater, April 27), which preserves the Balanchine heritage with verve;

and the New York City Ballet (New York State Theater, April 29 through June 29), which will mark the 10th anniversary of Jerome Robbins's death with a lavish selection of his dances.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Juilliard Dance Division

Masterworks of the 20th Century

Peter Jay Sharp Theater, NYC / March 26-29, 2008

Anila Mazhari-Landry and Spencer Theberge as The Bride and Husbandman in Martha Graham's Appalachian Spring. Photo by Rosalie O'Connor.

This spring, the Juilliard Dance Division celebrated its distinguished history with a program of three enduring works by choreographers associated with the academy: Antony Tudor and José Limón, both born exactly a century ago, and Martha Graham (born in 1894), who has always seemed eternal. Each piece concerns itself with what the New Yorker's art critic, Peter Schjeldahl, recently termed "plausible human interests and desires." Call this virtue passé at your peril.

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on April 1, 2008. To read it, click here.

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary