Seeing Things: December 2007 Archives

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater / Masazumi Chaya 35th Anniversary Celebration / New York City Center, NYC / December 18, 2007

Masazumi Chaya, Associate Artistic Director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Photo by Andrew Eccles.

I recall him vividly as a dancer. He was a powerhouse, but a deeply self-contained one, such as one sees in traditional Asian martial arts. This force never got in the way of lyricism when it was required--or sheer hi-jinks for that matter. He always seemed intent about something, be it the joy or anger or grief expressed by the choreography and music themselves, or possibly something beyond even that--perhaps the ecstasy of being an "acrobat of God."

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on December 20, 2007. To read it, click here.

Bookwormish-ness runs in our family. Over the generations it has seized the soul of my mother, me, my daughter, and my daughter's elder daughter, to name just the female victims. For example, whenever I take the subway with my young granddaughters--which is often, and often from one end of Manhattan to the other--I read aloud to them. Nearby passengers listen, smiling. Occasionally one of them says, "I remember that book from when I was a child."

There is nothing like a book. Nothing. People complain about standing in that endless line at the post office or curse the tedium of their daily train commute from suburb to city and back again. Such frustrating situations can be averted by always (always!) having a book with you. Why wallow in boredom when you can simply transport yourself into another world?

Arthur Mitchell, whose Standard English is meticulous, uses Black English to thrust a point home when the occasion or the audience will benefit from it. Back in the seventies, when he founded Dance Theatre of Harlem, a black classical-dance company--literally taking children off the street to make dancers out of them, as well as teaching them to speak, act, and dress with an elegance that made them royal ambassadors--he'd say, in the accent of his native Harlem, "If I ever catch you in the subway without a book in front of your face . . . ." The sentence was never finished but the implied threat was dire and effective.

I have no idea if young DTH aspirants are still subject to that rule but, when I was teaching dance writing at Barnard College, I used it with my students. I explained to them that their "subway book" had to be one they weren't required to read but, rather, chose to read, and I offered to buy books for any whose budget couldn't support the strain. Then, every few sessions of our weekly seminar, I'd require them to whip out their book of the moment and hold it aloft.

I also mentioned regularly that the activities most likely to contribute to one's becoming a professional writer were, first and foremost, to write a lot and, a close second, to read a lot. To my mind, taking courses in writing counted for nothing compared to learning from the examples of successful practitioners, from the pros who constituted the canon to purveyors of popular junk. Without realizing it at the time, I must have constantly mentioned many books that I loved and that had influenced my work.

The proof: Press tickets, a perk of performance journalists, usually come in pairs, and I regularly shared mine with my students. Occasionally, a dance company performing outside the usual Manhattan precincts would send a bus to collect journalists at Lincoln Center and deliver them to the outlying district in question by curtain time. Journalists were told the appointed hour of the bus's departure and understood that it would be strictly adhered to. One day I sat in a crowded press bus fuming because my student "date," who was usually reliable to a fault (scatterbrained conduct was simply not in her rep), had not shown up. Just as the doors of the bus were about to close for the trip, she staggered down the aisle to the empty seat beside me, lugging two outsize, bulging shopping bags emblazoned with the name of a familiar bookstore. "I'm sorry," she said, close to tears, "I was buying every book you mentioned all semester, and it took longer than I expected." I expected that, in the course of the next year, she would read them all. She was, as I said, reliable.

Obviously, I consider the acquisition of books a commendable enterprise. It is equally a serious problem. As every obsessive reader knows, books multiply in the night, and you soon find they are taking over your living space to a degree that can be outright dangerous. I remember that Edward Gorey, the inimitable author/artist, having filled his many bookshelves, took to creating tall, rickety, freestanding pillars of subsequently amassed volumes without which, apparently, he could not exist. Once, when I visited my dear friend the novelist Lynne Sharon Schwartz, she had ruthlessly plucked some 150 books from her overladen shelves and set them, spines up for easy identification, in cartons outside her apartment door. In front of them she had placed a boldly lettered sign: "TAKE AS MANY AS YOU WANT." I'm afraid I did. She offered me some shopping bags with a gleeful smile.

None of the solutions to holding the book invasion at bay are particularly satisfactory, though they may fend off a bibliophile's anxiety for a while. First of all, one can recognize the fact that book-owning isn't what it used to be. The books you buy these days, alas, self-destruct at headlong speed--sometimes the spines crack even on the first reading--so amassing a personal library for posterity isn't even possible. My grandchildren have pored over many of the picture books I originally bought for my children--volumes that are well worn from loving but incessant handling, yet still intact. The new books the grands acquire, however, will surely have collapsed long before their own children arrive on the scene.

As for me, after decades I got tired of using crammed bookshelves as wallpaper. I was never going to read Spinoza or Mickey Spillane--much as I thought I should when I acquired their works--so out they went, along with dozens of other worthy titles that had failed, over time, to seduce me. I felt little guilt about their afterlife. I live in a row house on the Upper West Side; any book put out on my stoop is adopted in ten minutes flat.

At the same time as I deaccessioned, I rediscovered the New York Public Library. Its catalogue is online. In the dead of night, your other chores finally done, you can order any volume in the entire city's circulating collection to be sent to your local branch. You will be notified by e-mail when it arrives there. Then, all you have to do is stroll over with your library card (surely the ticket to a world of wonders!) and pick it up. If you're a slow reader, you can renew the book online, more than once if no one else is clamoring for it. The most beautiful thing about the arrangement, though, is that the library makes these books go away--indeed, demands them back, threatening the dilatory with daily, if modest, fines. So now I can, theoretically at least, limit the books I give houseroom to the ones I need and the ones I love. Admittedly, I still have thousands.

I have also become a devotee of the adult version of being read to--audiobooks. While I'm allergic to electronic devices and congenitally incapable of understanding them, my husband, like many another man, is addicted to them. He has helped me acquire the spoken texts (there are several ways to do this without paying a cent, and even more choices if you have funds to spare), get them onto a tiny, portable gizmo that will play them (an iPod or other MP3 player) as I'm moving around, and learn the basic instructions for transferring word to ear--nothing fancy, mind you, like replaying a short section so admirable it begs to be repeated, just the essentials.

Now, when I do my regulation thirty minutes on the gym's Treadmill to Nowhere or perform routine household tasks--both occasions, for me, of excruciating boredom--I can hear stories. In the last two months, I've heard Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, Turgenev's Fathers and Sons, Natalie Babbitt's Tuck Everlasting, and F. Scott Fitzgerald's Tender Is the Night. (That's a lot of listening hours, but I have a streak of fitness fanaticism and I do a considerable amount of housework. I even iron, like Balanchine.) True, hearing a book is not really the same as reading the text, just as, between close friends, an e-mail lacks the texture of a letter. But, providing me with a way to elevate my heart rate without going out of my mind, audiobooks are on my short list of admirable contemporary inventions.

And then, just so you know, for books you can read without turning a page (though you do have to stay parked in front of a computer), there's Project Gutenberg, which provides thousands of works in the public domain. Granted, people who detest reading literature from a screen will hate this. The same folks, however, may be happy to know that pillars of bookdom--the Bible, Shakespeare--are readily accessible on the Internet and yield to keyword searches, a convenience that can't be claimed by our personally owned (perhaps inherited) bricks-and-mortar copies, though these are laden with other values, sentiment among them.

Valéry-Nicolas Larbaud called his two volumes of literary criticism Ce vice impuni, la lecture (reading, that unpunished vice). Vice only in the secret, all-pervasive delight it can bring, I'd say, along with the haunting fact that the addicted can't be cured of it. My friend Lynne has, finally, given up smoking, but would never consider giving up books, indeed would never be able to. Nor would I. Nor would my granddaughter Lili, who since she was seven, has marched down the street holding her current book open in front of her face, ignoring her elders' admonitions about the danger of accident, her very being enraptured by story. Reading may be marred by minor inconveniences, as stated above, along with possible solutions. Still, as I've mentioned, there is simply nothing like it. Nothing.

© 2007 Tobi Tobias

NOTE: This essay was written some five years ago--intended for posting on The Dance Insider in the "Vignettes" series I was writing there. My editor advised against going public with it, since it made me sound ungrateful toward the companies who issue press seats in pairs and might alienate readers who did not enjoy press-ticket privileges. I took his advice. This week, the twinned postings of my friend and colleague Eva Yaa Asantewaa and my ArtsJournal colleague Apollinaire Scherr persuaded me to offer it belatedly.

Since the rewards of writing dance criticism are largely aesthetic, rarely enough to pay the rent, one of the job's few perks is especially welcome: free tickets to the performance. Usually the freebies come in pairs--one seat for the critic and one for said critic's guest. Most critics enjoy the privilege and produce a companion for the show, though legend has it that one reviewer consistently arrived alone. "I need the other seat for my coat," he'd explain.

Having had access to press pairs for several decades, I feel qualified to report that securing a guest for that second seat is by no means simple. I'm even willing to admit--go on, call me a misanthrope--that sometimes it's more trouble than it's worth. Here's the drill: You decide who would be congenial company (remembering that high-maintenance friends are simply too exhausting when you're working) and who might enjoy the performance. Then, with a couple of back-ups on your list, you try to reach your first choice.

Understand that I'm writing from New York, where the populace is perpetually unreachable. You phone your prospective guest (let's call this person your PG) and get his answering machine or you send her an e-mail. And then you wait for his/her response. If she tries phoning you back, you're invariably out; thus the two of you are launched into the exasperating game of telephone tag. These unproductive maneuvers can go on at absurd length, unless one of you is sensible and bold enough to quit midway. If so, you are still without a date. A "no, thanks" response by e-mail is blessedly definitive--though it requires you to start again with another prospect, as did aborting that game of tag. An e-mailed "yes" simply engenders further e-mails--a dozen of them, easily, as the details of the arrangement are filled in. What time was it again? Which theater did you say? Where, exactly, shall we meet? Dinner before? Drink after? (More about the add-on socializing later.)

Mind you, merely managing to contact your PG doesn't mean you've got a date. Once the two of you are in direct communication, you have a good chance of finding the object of your invitation busy at the time of the performance. As I've indicated, I'm based in New York, where the citizens pride themselves on being too busy to breathe. Even if your PG is free in the relevant time slot, she may inform you (if she's frank as well) that, since she last shared your pair, she has developed a morbid loathing of--you name it: opera houses, black box theaters, traveling to Brooklyn; classical dance; modern dance; experimental dance; narrative, abstract, or dramatic dance; world dance (the stuff we used to call "ethnic"); Broadway musicals; hoofers old and new; butoh; mime; the tango; or works in progress. And so you must start your search all over again, should you have the time to do so. And the patience. And the desire. Often you discover that you have expended your full measure of all three on Round One.

Say, however, that you've been lucky enough to have secured yourself a companion for the show. Next you run smack up against a peculiar truth about such outings. You may be attending the performance for work purposes, but your guest is more likely to be doing so for the normal reasons people go to the theater: to be entertained and to socialize. So, having said yes to the show, your PG is now, quite logically, suggesting dinner before or a drink after. Problem is, I'm a dance critic; I can't afford to dine out more than once in a blue moon. Besides, the restaurants reasonably close to the major theaters have become so crowded and noisy, meaningful conversation--assuming that's what you're after--is precluded. For me, post-performance gallivanting is equally hard. Either I have to write overnight or I have to get up early in the morning if I'm going to fit the gym into my crazed schedule. (As it is, when Twyla Tharp frequented our mutual local gym, she was already on her virtuous and athletically toned way out of there by the time I arrived.) One friend commented wryly after a performance, as we headed briskly for our respective neighborhoods, which are separated by the width of Central Park, "Thanks for the chance to see the show. We should get together one of these days."

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on December 7, 2007.

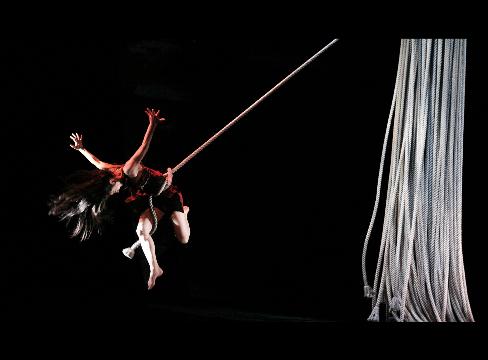

Satchie Noro swings from ropes while performing in "Au Revoir Parapluie," directed by James Thierree, at the BAM Harvey Theater in New York on Dec. 4, 2007. Performances will continue through Dec. 16. Photographer: Julieta Cervantes/BAM via Bloomberg News

Dec. 7 (Bloomberg) -- A woman in crimson hangs upside down in a tangle of thick ropes, later soaring through the air in a white nightgown, like Peter Pan's Wendy. An acrobatically inclined man is defeated by the motion of a skeletal rocking chair. The stage floor gets pried apart to make a lake in an improvised rice field, while the plants become whimsically pliant swords in a mock duel.

James Thierree's ``Au Revoir Parapluie'' (Goodbye, Umbrella), at the BAM Harvey Theater through Dec. 16, is a loosely joined performance of skits involving acrobatics, mime, magic tricks, aerial feats, a bit of singing and sundry aspects of dancing. Thierree was supposedly inspired by the Orpheus and Eurydice myth -- loss, search, death-defying retrieval -- but you'd never know that.

What you do wonder, unless you're simply content to be charmed by the absurd, is how he's going to make the whole business cohere. It does so only vaguely and succeeds, instead, through inventive props, the intrepid spirit of its five performers and a vein of pathos that gives the pervasive silliness some gravity.

Creator of the French troupe Compagnie du Hanneton, Thierree plays the hero of the show, a lovable charmer unable to cope with the everyday actions we take for granted -- putting on a jacket, sitting in a chair -- let alone with securing a lover. Though he lacks the exquisite timing of a world-class comedian, perhaps because he hasn't yet learned the value of stillness, he's undeniably a multitalented performer.

Miner's Helmet

The rangy, bemused Magnus Jakobsson, wearing a miner's searchlight helmet, provides the magic. His best stunts have no visible props or results; it's all in the mime. Kaori Ito, a tiny, hyperkinetic woman, dances the role of the hero's over-eager pet. The luscious Satchie Noro, who does the aerial work, is the hero's elusive love, while a singer, Maria Sendow, appears in settings involving the seedy red velvet and tacky gold trim of an opera house in picturesque decline.

The decor, especially its huge absurdist props, is a main character in the show. The most prominent items are a giant ladder providing an extended balcony, which gets pushed around on a conglomeration of dubiously reliable wheels -- think Claes Oldenburg -- and a flies-to-floor hanging of ropes that looks like an old-fashioned wet mop on steroids.

Thierree inherited the right genes for his work. His parents were prominent in advancing the nouveau cirque genre, known best in the U.S. through Cirque du Soleil. His grandfather was Charlie Chaplin; his great-grandfather, Eugene O'Neill (not given to the lighthearted, granted, yet certainly a theatrical innovator). Thierree is already 33, but I have a hunch he's only beginning to harness his imagination.

At the BAM Harvey Theater, 651 Fulton St., Brooklyn, through Dec. 16. Information: +1-718-636-4100 or http://www.bam.org.

`Phoebe Snow'

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, at the New York City Center through Dec. 31, has wisely ranged through its attic and come up with a winner -- Talley Beatty's 1959 ``The Road of the Phoebe Snow.'' The revival, staged by Masazumi Chaya, the company's associate artistic director, proves that a work typical of its time can burn bright today.

The dance shows us a 14-strong bevy of young people, who may be have-nots but still retain some romantic hope as well as immense vitality. The group's taut body language, however, shows that it's living close to the edge and can just as easily turn vicious.

In an emotionally potent duet danced by Briana Reed and Glenn Allen Sims, the woman is just a callous man's passing sexual fancy. This passage is immediately succeeded by a luminous pas de deux of unsullied love between Linda Celeste Sims and Clifton Brown.

Trouble Starts

The next thing you know, big trouble starts. Provoked by one malevolent guy, the crowd turns on the radiant pair, perhaps jealous of its brief, unclouded joy. The mob viciously beats the man; the woman is raped and so traumatized she throws herself under a passing train.

The construction of the piece is knife-sharp, as is its message. The passenger train named the Phoebe Snow was a creation of advertising in the early 20th century. The Lackawanna Railroad featured trains fueled by anthracite, a hard coal that left passengers' clothes unsullied, unlike the soot-producing trains fueled by soft bituminous coal. Ads depicted Phoebe as a privileged pale-skinned young woman elegantly attired in immaculate white. Beatty, who grew up along the trains' route, tells the gritty truth.

At City Center, 131 W. 55th St., through Dec. 31. Information: +1-212-581-1212 or http://www.alvinailey.org.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on December 4, 2007.

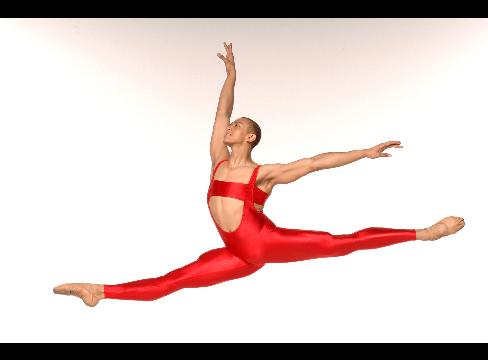

Clifton Brown from the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater rehearses for Maurice Bejart's "Firebird" in New York on Aug. 21, 2007. Performances of the show will continue at the New York City Center through Dec. 31. Photographer: Eduardo Patino/Alvin Ailey Dance Theater via Bloomberg News

Dec. 4 (Bloomberg) -- Seeing the late Maurice Bejart's ``Firebird,'' the centerpiece of the gala that opened the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater's five-week season at the New York City Center on Nov. 28, you'd never guess that the French choreographer was celebrated and reviled for works that were spectacular and scandalous. Unless, of course, you expected to see a ballerina in a red-feathered tutu in the title role rather than Bejart's choice of a gorgeous young man sheathed in shiny, fetchingly cut vermilion spandex.

Bejart uses a condensed version of the Stravinsky score first (and probably best) choreographed by Mikhail Fokine in 1910, but he devised an entirely new libretto. Rejecting the Russian folk tale usually matched with the music, he presents a group of revolutionaries outfitted in camouflage. They are prodded into action (against a never-specified enemy) by the title character, who seems to preach a gospel of love undercut, where necessary, by violence. When this Firebird dies of exhaustion, another arrives, phoenix-like, to replace him, so that the vision of an ideal world is never extinguished.

Choreographed in 1970, this ``Firebird'' is, thematically, very much of its time. The piece uses a classical-ballet vocabulary (rather than the jazz-inflected modern dance that is the Ailey's default mode), and the company's versatile and personable dancers do well with it. Yet the work is so neatly and conventionally constructed, it looks old-fashioned.

`Saddle Up!'

Other new additions to the company's repertory will surface in the course of the season. So far, I've seen ``Saddle Up!'' about which the less said, the better. Choreographed by Fredrick Earl Mosley to an engaging composite score involving Edgar Meyer, Mark O'Connor, and Yo-Yo Ma, it's a puerile take on already hokey Wild West themes. The dancers were as sassy as could be under the dismal circumstances.

Even if its repertory generally leaves much to be desired, the Ailey has some remarkable assets. It has the savviest, most financially productive board of directors of any dance company I know and an artistic director, Judith Jamison, who is unafraid of running a tight ship according to her vision. Jamison also boasts a theatrical presence and timing that have only expanded since her dancing days.

Judith, Judith, Judith

As she emceed the gala, even her costume added to her effect: shaved head, red specs, outsize dangling earrings, a silver necklace as formidable as a breastplate and a floor- sweeping black monk's robe lined with red, the traditional Ailey accent color, visible when her bold stride made it flap open.

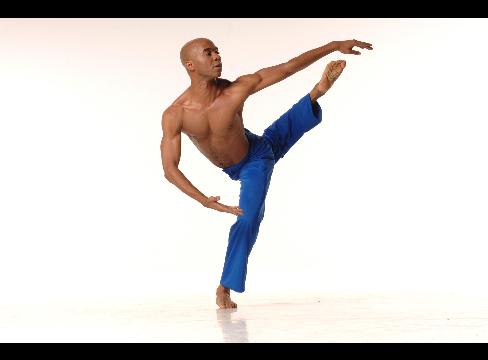

And the dancers themselves are unbeatable. It seems almost arbitrary to single out a few favorites featured in the gala program. The young Clifton Brown was pure poetry in the title role of ``Firebird.'' Jamison's recent restaging of the solo Ailey himself choreographed to Duke Ellington's ``Reflections in D'' showcased Matthew Rushing, a 15-year veteran with the troupe. He's a small, exquisitely proportioned dancer whose bare arms and torso would be a credit to the most rigorous gym and a sweet, gentle face. His technique is formidable; his style, lyrical.

Matthew Rushing from the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater rehearses for "Reflections in D" in New York on Aug. 21, 2007. Performances of the show will continue at the New York City Center through Dec. 31. Photographer: Eduardo Patino/Alvin Ailey Dance Theater via Bloomberg News

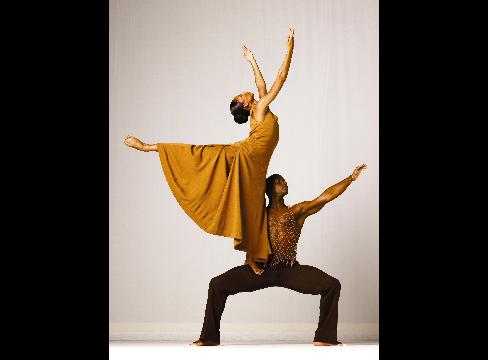

In Ailey's signature piece, ``Revelations,'' Linda Celeste Sims and her husband, Glenn Allen Sims, give an unsurpassable account of the rapt adagio duet ``Fix Me, Jesus.'' They displayed an intimate rapport with their subject (an oppressed or imperfect soul seeking help), the spiritual to which it's choreographed and each other (those phenomenal balances are possible only through deep mutual trust).

Linda and Glenn Sims from the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater rehearse for "Revelations" in New York in this undated handout photo. Performances of the show will continue at the New York City Center through Dec. 31. Photographer: Andrew Eccles/Alvin Ailey Dance Theater via Bloomberg News

Their unwavering focus, which excluded even the smallest extraneous movement, epitomized the observation offered by the evening's guest of honor, Russell Simmons: ``Dance is living prayer.''

At 131 W. 55th St. through Dec. 31. Information: +1-212-581-1212; http://www.alvinailey.org.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

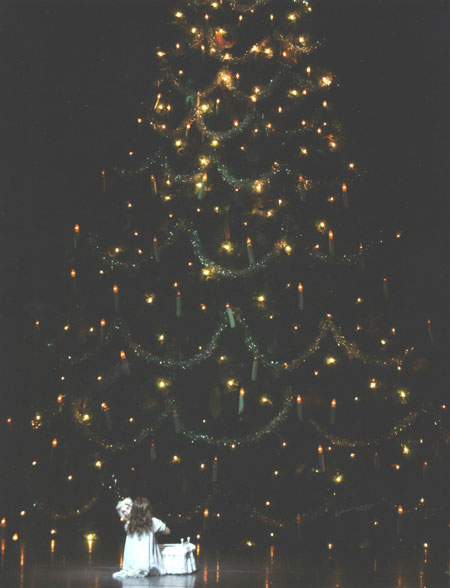

New York City Ballet: George Balanchine's The Nutcracker / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / November 23 - December 30, 2007.

Marie and the tree from New York City Ballet's The Nutcracker by George Balanchine. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

The Nutcracker--in George Balanchine's version for the New York City Ballet, the most skillful, intuitive, and moving that I've ever seen--is an essay in contrasts, both physical and social.

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on November 28, 2007. To read it, click here.

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary