Seeing Things: November 2007 Archives

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on November 29, 2007.

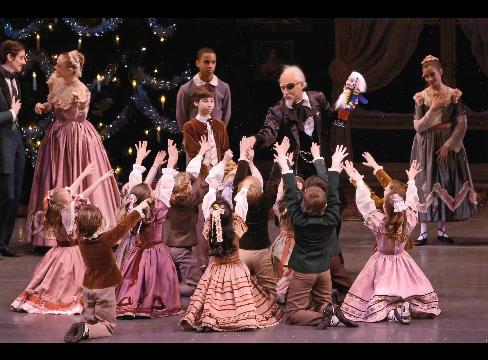

Robert La Fosse, standing second from the right, as Herr Drosselmeier, performs in the New York City Ballet production "The Nutcracker" in New York in this undated photo. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

Nov. 29 (Bloomberg) -- A bracing tonic for the Scrooges among us is ``The Nutcracker,'' choreographed to Tchaikovsky's captivating score by George Balanchine for the New York City Ballet.

In the course of its annual five-week run at the New York State Theater (this year, through Dec. 30), it regularly features the company's seasoned stars as well as stars-in-the making; alternating casts of some 40 Lilliputian children from the School of American Ballet, impeccably rehearsed by Garielle Whittle; and scenic wonders such as a Christmas tree that grows to a surreal height, lights flickering.

You know the story: At a decorous Christmas Eve party long ago, Godfather Drosselmeier gives Marie, the prepubescent daughter of the house, a magical nutcracker that sets in motion striking transformations and wish fulfillments. These climax in a visit to the Sugar Plum Fairy, who reigns over the Land of Sweets, with Marie escorted by the nutcracker now transmuted into the young prince of her girlish dreams.

The opening night's Sugar Plum Fairy, Maria Kowroski, mistress of adagio dancing, gave a ravishing account of the ballet's climactic duet. Her Cavalier, Charles Askegard, was secure enough to toss her into the air for a moment midway through their fish-dive maneuver that is already a tour de force: ``Look, Sugar, no hands!''

Maria Kowroski as the Sugar Plum Fairy, rear, and Charles Askegard as her Cavalier, perform in the New York City Ballet production "The Nutcracker" in New York in this undated photo. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

More surprisingly, Kowroski was radiant and tender at her entrance, reigning over the flock of tiny angels that scoots across the stage in interweaving patterns as if on ball bearings.

Ashley Bouder, as the Dewdrop leaping and whirling her way through a corps of Flowers, was even more astounding than usual in her athletic brilliance. Audiences adore her. I still have reservations about her dancing, which is two-dimensional rather than sculptural, a phenomenon that a camera could render perfectly. Live dancing demands more depth.

Nothing Tragic

I also miss the whiff of tragedy that Heather Watts once brought to this role, as if to reflect the evanescence of a dewdrop's perfection. But perhaps that is too much to ask these days when bravura technique is valued above subtler qualities.

The generation of nascent ballerinas was represented by Erica Pereira and Rachel Piskin, not long out of their student years at SAB. They seconded the remarkable young virtuoso Daniel Ulbricht in the shamelessly politically incorrect pseudo-Chinese dance, ``Tea,'' which represents one of the treats displayed in the second act's ``Land of Sweets.''

Among the children in leading roles, Jonathan Alexander stood out for his spontaneous exuberance as the naughty kid brother. The all-important character role of Herr Drosselmeier lies at the other end of the age scale. Playing the enigmatic inventor and magician who makes Marie's dreams (as well as the nightmares) come true, Robert La Fosse has toned down his earlier over-the-top interpretation. Now he displays just the right blending of strangeness and fantasy.

Through Dec. 30 at the New York State Theater, Lincoln Center. Information: +1-212-870-5570; http://www.nycballet.com.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

When I was growing up, my mother pointed out to me that, among my aunts, uncles, and myriad cousins (along with any spouses and offspring that had accreted to them), the ones that I liked best invariably had the "worst" personalities, moral characters, and behavioral track records. At least according to the standards of our petit-bourgeois world. This was true, but not entirely true. My absolute all-time favorite family member, my mom's elder sister, Ann, was a saint--all self-effacing and genuine sweetness and tenderness. I adored her and named my daughter after her. I still cherish her memory and talk about her to my daughter's daughters, my grands. But I digress.

Once I got considerably older, I noticed how many of my closest friends (a majority of them artistic types like me) were "peculiar," as my mother would have put it--vulnerable, even fragile creatures, given to unconventional behavior because they recognized norms only grudgingly as they went about their business of making the world continually new. I was happy, at this point, to discover what Morison Cousins, the great designer of Tupperware, said: "People who are the most interesting are often neurotic. The ones with good sense almost lose their allure."

© 2007 Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on November 16, 2007.

Nov. 16 (Bloomberg) -- Nine casually dressed women move as a unit to Brian Eno's ``Neroli,'' which hovers on the edge of silence. Their dance is called ``Humus'' (Latin for ``earth'').

They're introspective and sensuous, hunkering down to sway torso and pelvis as if they were so many waves in the sea, or recumbent, stretching and folding their legs like languid odalisques.

This is the most congenial section of ``Shalosh'' (``Three''), choreographed by Ohad Naharin for his Tel Aviv- based Batsheva Dance Company. Created in 2005, the 70-minute triptych is on view at the BAM Howard Gilman Opera House through Saturday.

The Tel Aviv-based Batsheva Dance Company choreographed by Ohad Naharin in this undated photograph released to the media on Friday, Nov. 16, 2007. Source: BAM Howard Gilman Opera House via Bloomberg News.

The introductory segment of the piece, called ``Bellus'' (``Beauty''), begins with 10 dancers facing the audience with calm interest, as if they were the spectators and the audience the show. The group disperses, leaving Erez Zohar to execute a solo of peculiar moves linked not by mood or meaning but simply by the dancer's fluidity and physical power. Some of these moves are undeniably beautiful, but as if by accident; others are downright weird.

Eventually, he strides off with the busy officiousness of someone with a lot to do. His material is then given new contexts by other soloists, a couple in the shy bloom of love and the full cast we met at the outset.

The final section of the dance, cagily called ``Seus'' -- which can mean either ``this'' or ``not this'' -- sets 17 dancers jiving to a raucous mix of pop music. Its most eloquent passages are a duet for Sharon Eyal and Guy Shomroni suggesting that love hurts and another for two guys, Gavriel Spitzer and Matan David. Based on old-time social dances, it is delectably tender and funny.

Dusky Lighting

The piece finishes with a gorgeous one-liner in which the dancers, barely visible in dusky lighting, mill about grotesquely like the tame monsters in Maurice Sendak's ``Where the Wild Things Are.'' The accompaniment is a Glenn Gould recording of Bach's ``Goldberg Variations.''

Co-founded by Baroness Batsheva de Rothschild and Martha Graham in 1964, the company has shifted with the times -- radically since Naharin took over as artistic director in 1990. Today it features his work primarily and tours worldwide, distinguished for dancing that alternates -- often in the space of seconds -- delicate, subtle phrases with huge, charged moves and is unafraid of either the ostensibly ugly or silly.

Naharin emphasizes the fact that his company now trains in a method called Gaga. He developed it to rehabilitate himself after being severely incapacitated by a spinal injury. Gaga is part of an increasingly popular trend that has dancers supplementing or even discarding a highly codified technique that they've mastered for a less rigid movement language designed to free the body while making it flexible, strong, and self-aware.

Batsheva Dance Company is at the BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, 30 Lafayette Ave., Brooklyn, through Nov. 17. Information: +1-718-636-4100; http://www.bam.org.

Devoid of Spontaneity

Not every heartening start has a happy ending. The Pennsylvania Ballet, at the City Center in a rare visit to our town, was founded in 1963 by Barbara Weisberger, a protegee of George Balanchine. It benefited from a Ford Foundation sponsorship to elevate promising companies from the status of ``regional,'' with its gloomy implications. The troupe reached its highest luster in the decade from 1973 to 1982 under the direction of Benjamin Harkarvy, when its productions of Balanchine's works were widely considered worthy alternative readings to the New York City Ballet's.

Since then, matters seem to have gone downhill. ``Serenade,'' the Balanchine signature work that opened the five-day engagement, was given a conscientiously prepared showing devoid of both spontaneity and mystery, to say nothing of technical aplomb.

Contrived Escapades

The dancers were far more at ease in the other piece on the program, ``Carmina Burana,'' to the melodramatic Carl Orff score about lust, spirituality and life's subjection to the wheel of fortune. A new version by the company's resident choreographer, Matthew Neenan, offers 55 minutes of contrived escapades, their gaudy, peculiar costuming thwarting any meaning the dance may have aspired to.

The Pennsylvania Ballet is at New York City Center, 131 W. 55th St., between Sixth and Seventh avenues, through Nov. 18. Information: +1-212-581-1212 or http://www.citycenter.org.

(Tobi Tobias is the New York dance critic for Bloomberg News. The opinions expressed are her own.)

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on November 9, 2007.

Nov. 9 (Bloomberg) -- Swathed in black, not an inch of flesh visible but for their faces, hands and an opening at the spine or chest, eight dancers cover the stage with a heavy, awkward gait. Outstretched arms angled, torsos canted forward, they strike the floor with their sturdy shoes, their long inky skirts flapping like the wings of wounded birds.

Tero Saarinen dances with member of his company while performing "Borrowed Light" at the Brooklyn Academy of Music Opera House in the Brooklyn borough of New York, on Nov. 7, 2007. Photographer: Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos via Bloomberg News

The Finnish choreographer Tero Saarinen's ``Borrowed Light,'' which opened Wednesday at the gala celebrating the Brooklyn Academy of Music's 25th Next Wave Festival, portrays the Shakers, a Protestant sect that arose in the 18th century, seeking spiritual perfection. Believers lived communally, with Spartan simplicity, observing a strict separation of the sexes. Their rituals included a cappella singing of hymns composed by the worshippers and ecstatic dance with trembling and wrenching movements intended to cast out sin -- and perhaps the tension of thwarted sexuality.

Eight black-clad singers of the Boston Camerata -- an early-music ensemble led by Joel Cohen, who co-opted the Shaker music -- move fluidly among Saarinen's dancers, their voices intensifying the otherworldly element of the piece.

In particular, a solo danced by Carl Knif epitomizes the struggle between the sacred and the profane. Begun in silence, its motifs are outflung limbs, trembling fingers and a torso curving violently forward and back, making the whole body rock and stumble. The choreography, for small single-sex clusters and, of course, the full-cast passages, emphasizes the communal support these isolated people must have given one another despite their inner conflicts and dark nights of the soul.

Perfect Design

Design is a prominent partner in the effect of ``Borrowed Light,'' and it is perfect. Erika Turunen created the handsome costumes; Mikki Kunttu has the performers moving in a rectangle of glowing illumination in an otherwise dark space bordered by stepped platforms.

The title of the dance comes from the Shaker architectural practice of putting windows in interior rooms, so that daylight could be shared, making the workday longer. ``Put your hands to work, and your heart to God'' was a Shaker motto. One result of that devoted labor was the austere, graceful furniture that has outlasted the influence of the sect itself.

The dance is striking and intelligently crafted, but its conclusion -- a melodramatic collision of the sexes succeeded by a consoling wallow in pathos -- makes it unworthy of being compared to its great precedents -- Doris Humphrey's ``The Shakers'' and Martha Graham's ``Primitive Mysteries,'' both created in 1931 and still the last word on plainspoken religious fervor.

Through Nov. 10 at 30 Lafayette Ave., Brooklyn. Information: +1-718-636-4100; http://www.bam.org.

Garth Fagan

``Edge/Joy,'' an ingenious new work by Garth Fagan featured in his company's weeklong run at the Joyce Theater, has a bubbling, playful air and a serious subject: how we see.

The human eye naturally gravitates to the center of the area it's observing, the place where the important stuff is supposedly happening. Fagan challenges that habit by putting the action at the edges of the stage.

Solo, in pairs or trios, the sassily clad dancers animate borders and corners, leaving the spectators' usual point of focus a mysterious void. Every entrance and exit is a small surprise, and each dancer seems intent on his or her own agenda. From time to time, the stage fills with the piece's full dozen dazzling performers, passing each other as if at rush hour or with small units doing disparate things, a la Merce Cunningham.

Look Aside

``Edge'' is a dance that refuses to tell you where to look, yet the jigsaw-puzzle choreography magically coheres. The music, by Ricardo Zohn-Muldoon -- for inventively combined piano, strings, woodwinds and percussion -- cooperates in every way.

The Jamaican-born Fagan's signature style mixes the elegant lines, razor-sharp execution and phenomenal balances of ballet, the percussive isolations of jazz and the earthiness of modern dance with Afro-Caribbean polyrhythms.

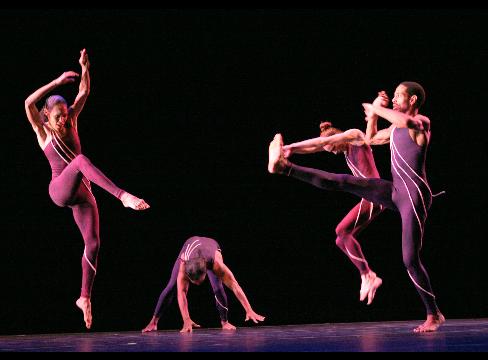

Nicolette Depass, Steve Humphrey, Micha Scott, and Norwood Pennewell perform in the Garth Fagan Dance, "Senku" in Oct. 17, 2006. Photographer: Steven Schreiber/Ellen Jacobs Associates via Bloomberg News

Fusion is a commonplace these days, but Fagan's style is uniquely his. Too easily, the style itself can become the whole show, though in ``Edge/Joy'' it's merely the native language of a choreographer out to tell you that byways can be more rewarding than the highway.

Through Nov. 11 at 175 Eighth Ave. Information: +1-212-242-0800; http://www.joyce.org.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on November 2, 2007.

Julieta Cervantes and John Jasperse perform in "Misuse Liable to Prosecution" in this image released to the media on Thursday, Nov. 1, 2007. Photographer: Julieta Cervantes/John Jasperse Company via Bloomberg News

Nov. 2 (Bloomberg) -- A few dancers you can barely see wander through a forest made from hundreds of suspended plastic coat hangers, lights boldly flickering among them like errant stars. It's not a dance moment, really, but it is a theatrical one, and one of the most beautiful and clever in John Jasperse's new ``Misuse liable to prosecution.'' The piece and its eclectic percussive score by Zeena Parkins, mistress of the electric harp, were commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music for its 25th Next Wave Festival.

As you enter the BAM Harvey Theater, where the piece will play through Saturday, Jasperse lies supine upstage, his upended legs crocheting a scarf for a giant with the thick orange extension cord familiar from construction sites. A lean, fluid man of 44 with an unassuming manner, given to making eccentric behavior look normal, he moves on to address the audience through an orange traffic cone serving as a megaphone.

Without rancor, he delivers a slew of statistics revealing how skewed the scale of monetary reward is in our society. Judge Judy makes millions more than the justices of the Supreme Court combined. He himself -- a star and a veteran in the world of experimental dance, though he's too modest to say so -- earns $26,000 a year as head of his company. His dancers receive $15 an hour rehearsal pay.

Milk Crates

The warning that gives the work its title is usually emblazoned on plastic milk crates that people with limited means -- students and artists, for example -- grab off the street, repurposing them for personal use. Indeed, every item in the piece, Jasperse declares, from decor to costumes and props, has been found, borrowed or stolen. The point of ``Misuse'' is to explore our culture of consumption and waste and how those who don't make much sometimes make do. Jasperse does so genially and ingeniously.

As usual, Jasperse has the dancers interact with the ``stuff'' of his piece, and so we get a dance for two women with dozens of plastic water bottles that they line up between their legs, letting a floor-level light gleam through them until they look like giant diamonds. Then they crunch the bottles into trash.

All five dancers join for a choral segment that involves meticulously folding well-worn jeans, then viciously whipping them about like lariats. After much playful manipulation, a limp bean-bag chair becomes a shroud for Jasperse's head and an inflatable mattress collapses over a female dancer's, so both end up groping their way through the hanger forest, bare-legged and blind.

Their Bodies, Themselves

Even more interesting are passages in which the dancers, in pairs, simply use the resources of their own bodies, extending themselves beyond the borders of formal technique. Jasperse credits his dancers' contributions to the choreography, and a fascinating double duet has an air of improvisation. The performers tangle with each other as if to discover new uses for their limbs or the ways in which a pair of bodies can interact without romance to nudge them along. The movement begins gently, with an air of exploration, then grows wilder and more powerful until the quartet crawls offstage, ungainly but game to the last.

Parkins's score, live and pre-recorded, is all over the map. Orphan objects (broken typewriters, tea kettles and the like) are used to evoke cars, trains, birds or eerie whisperers. We are assured, too, that the D.J.'d material comes from vinyl records played on found turntables.

Through Nov. 3 at the BAM Harvey Theater, Fulton Street at Ashland Place in Brooklyn. Information: +1-718-636-4100; http://www.bam.org.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary