Seeing Things: October 2007 Archives

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on October 30, 2007.

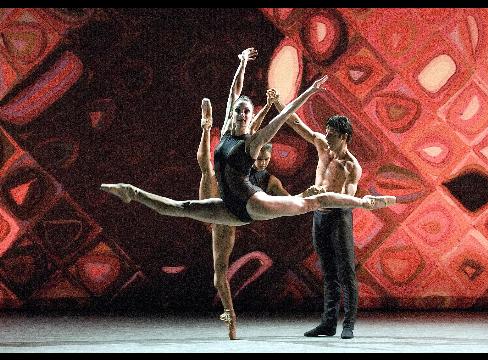

Kristi Boone, Misty Copeland and Marcelo Gomes perform in "C. to C. (Close to Chuck)," in this photograph released to the media on October 29, 2007. Photographer: Gene Schiavone/American Ballet Theatre via Bloomberg News

Oct. 30 (Bloomberg) -- A strong sultry beauty in a dark gleaming unitard struggles endlessly in her powerful partner's embrace. Or is it a stranglehold?

The forceful episode serves as the centerpiece of choreographer-on-the-rise Benjamin Millepied's new ``From Here On Out'' for American Ballet Theater, performing at New York's City Center this week. The duet's subject seems to be a cruel co-dependency that masquerades as love. Remarkably, the choreography conveys no human feeling, neither depicting nor eliciting empathy. Its extravagant shapes and ferocious energy are merely decorative.

The balance of the ballet has five other anonymous, look- alike couples making the stage vibrate with their attack -- as partners and in phalanxes, the sexes sometimes set against each other.

The important components are unbelievably svelte, fluid bodies, killer speed and menacing glamour. Nico Muhly's score, percussive and haunted, fits the occasion perfectly. The overall effect is a sleek portrait of contemporary high-end urban life. The ballet -- cleverly constructed, to be sure -- offers a snapshot of the direction classical ballet is taking today.

`C. to C.'

If Millepied's ballet pictures the world as an ominous place, the currently popular Finnish choreographer Jorma Elo contends that its inhabitants are chronically spastic. He applies this signature style to his new ``C. to C. (Close to Chuck),'' which looks like a sextet of robots aiming to add sex to their skill set.

The dance is choreographed to Philip Glass's ``A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close,'' the score played onstage by pianist Bruce Levingston. Close, whose art figures as a backdrop, is the painter who heroically managed to continue his career after being paralyzed by a spinal aneurysm. Close, Glass and Elo all build their art from small fragments, hypnotically repeated with slight variations. However, the painter and composer make the whole cohere, brilliantly. I can't say the same for the choreographer.

In ``C. to C.,'' as usual, he has his dancers executing disconnected, unfathomable gestures, even occasionally breaking into a few brief flowing phrases. Invariably, though, potential partners can't relate to each other with any ease or joy -- or even meaningful hostility. The costumes, by the fashion designer Ralph Rucci, are striking, until the wearers have to shed their stiff black skirts and move.

`Ballo Della Regina'

The brief season managed to cram in several terrific golden oldies, among them George Balanchine's 1978 ``Ballo della Regina,'' an abstract piece for a hierarchy of women and a single man, set to an outtake from Verdi's ``Don Carlos'' that begs to be danced. Originally it showcased the scintillating technique and unaffected style -- both echt-American qualities - - of the New York City Ballet's Merrill Ashley. As staged by Ashley for ABT, the production is a little miracle -- crisp and clear, as if it were happening in the sky on a bright, windswept day.

I saw Gillian Murphy in the ballerina role and, while no dancer can ever replace another, she did Ashley proud. Murphy's partner, David Hallberg, charging through space, whirling as if in a vortex, eclipsed even his personal best. The four soloists and the corps de ballet looked elated, as if they'd been schooled in a mode of dancing they'd never dreamed of.

The revival of Antony Tudor's 1975 ``The Leaves Are Fading,'' a plotless nostalgic idyll, served as a reminder of the choreographer's long-term association with ABT and the profound feeling a physical gesture can convey. Staged by Amanda McKerrow and John Gardner, both of whom once danced in it, it hasn't yet retrieved the flow and spontaneity with which Tudor himself had his dancers perform his ingenious designs.

Still to come is the company premiere of Twyla Tharp's 1979 ``Baker's Dozen,'' an early work full of ingenious, ramshackle joy. All three blasts from the past are only a small part of the proof that the 1970s was an exceptionally rich period for choreography. What does the first decade of the 21st century offer to equal it?

Through Nov. 4 at City Center, 131 W. 55th St. Information: +1-212-581-1212; http://www.abt.org.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

American Ballet Theatre: Antony Tudor's The Leaves Are Fading / New York City Center, NYC / October 24, 26, 28, 31, and November 3.

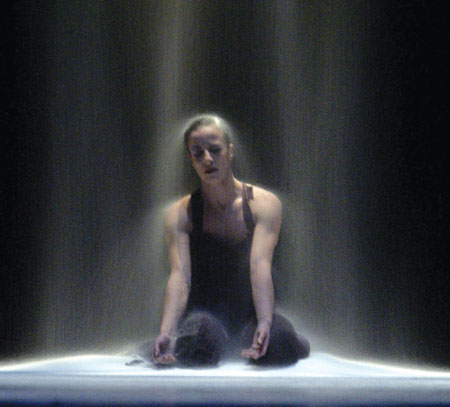

Julie Kent, Marcelo Gomes and Melissa Thomas of American Ballet Theatre in Antony Tudor's The Leaves are Fading. Photo by Rosalie O'Connor.

The Leaves Are Fading is an evocation of youthful love and friendship framed by one of the most famous unadorned cross-stage walks in ballet history. The path is traced by a woman in a ground-brushing, apple-green dress, seemingly lost in thought. Though she is onstage only at the opening and close of Leaves, the half-hour of dancing between her brief appearances seems to emanate from her thoughts and mood. She lends the ballet its fragrance of nostalgia.

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on October 26, 2007. To read it, click here.

Compañía Nacional de Danza / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Brooklyn, NY / October 16, 18-20, 2007

Compañía Nacional de Danza's Yolanda Martín in Nacho Duato's White Darkness. Photo by Fernando Marcos.

The strongest element of Compañía Nacional de Danza's show was the dancers themselves, who were greeted by roars of deserved adulation on the curtain calls. They are a feisty bunch . . . and their dancing, ebullient or ferocious as the occasion requires, is contagious, an advertisement for life.

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on October 18, 2007. To read it, click here.

Oct. 19 (Bloomberg) -- Christopher Wheeldon's Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company opens its debut season with dances by William Forsythe, Edwaard Liang, Liv Lorent and Michael Clark. At Wednesday's premiere in Manhattan's City Center, the deconstructed-ballet pas de deux from Forsythe's ``Slingerland'' (where the ballerina's tutu looked like an outsize potato chip) had Wendy Whelan magically making all the eerie maneuvers fluent.

Otherwise, the highly anticipated event featured Wheeldon, Wheeldon and more Wheeldon: two substantial pieces and various bagatelles by the 34-year-old choreographer, launching the next stage in his career as artistic director of his own company after six years as resident choreographer of the New York City Ballet.

Named for one of Wheeldon's signature works, Morphoses is just now a pickup group of sympathetic moonlighting stars and stars-to-be. With former City Ballet principal Lourdes Lopez as executive director, the group has survived a long run-up of organization and fundraising. It has been offered a home by the City Center and secured support that includes commissioning dances from London's Sadler's Wells Theater.

Despite the excitement and hope that sheer novelty generate, the future of Morphoses seems iffy, judging from the first performance.

Of the longer works, ``There Where She Loved,'' danced to songs by Chopin and Kurt Weill, offers loosely knit, cannily designed takes on romance, blithe and -- in an extended duet for Maria Kowroski and Michael Nunn -- otherwise. ``Fools' Paradise,'' for nine dancers, is simply unfathomable, a puzzle of marvelously adept bodies variously arranged for pictorial effect and a decor of shooting stars.

Suave Craft

Technically, Wheeldon's choreography shows wide range and suave craft, but the work rarely engages the viewer emotionally. That's the problem in a nutshell. It's not even evident that Wheeldon's own feelings are engaged.

Wheeldon has led a charmed life as a choreographer since 2001, when his gift for making dances was so evident to the New York City Ballet that the company created the position of resident choreographer for him. His work has also been in demand from major companies worldwide; everyone wants a Wheeldon.

Sacrificing this enviable state of affairs for the chancy alternative of starting his own company proves Wheeldon's conviction, though his goals are clearly still evolving and occasionally naive. Ignoring the fact that classical ballet is rooted in tradition, for example, Wheeldon declares he's ready to slough off the past (including saying goodbye to Balanchine) to make cool, sexy dances -- his words -- that will lure a younger audience.

Collaborative Art

He also wants his relationship to his dancers to be collaborative, while despotism remains the default mode in most classical companies. There's a good argument for it when the leader has genius and is not unduly concerned with individual dancers' personal happiness.

If Wheeldon is to maintain a real company, he will need substantial financial backing on an ongoing basis. This may be hard to come by once the first flush of enthusiasm for his venture begins to fade.

It's time for Wheeldon to start making dances that are more than just a handsome but superficial idea of what's contemporary, studded with everything he's dutifully absorbed from dancing the works of Ashton and MacMillan in London, then Balanchine and Robbins in New York. He needs to dig deeper, if only because even his admirers are starting to complain.

At 131 W. 55th St., through Oct. 21. Information: +1-212-581-1212; http://www.morphoses.org.

Have you considered how rare it is to encounter an ugly baby? Post-six months, that is. But apart from C-section arrivals, the newborn, still supine in its crib or pram, entirely exposed to the gaze of the curious, usually bears for at least several weeks the marks of its struggle out of the womb, a journey it makes provided with no experience to assure it that this, too, shall pass and no concept of future joy. The infant's physical battle scars--perhaps its psychic ones as well--disappear with time, and time, as well as interaction with other creatures of the human species, seems to make its features harmonize just as its limbs gradually acquire coordination. By the half-year mark, most fledglings are enchanting in one way or another.

But it's the "ugly" babies that fascinate me. Those with the ears akimbo, the eyes tiny and too close together, the eyebrows perennially in frown mode, the skin sallow, blotched, or irregularly puffy, the expression grave or worried, even in situations promising pleasure.

I have enormous affection and hope for these babies. First of all, obviously, because Hans Christian Andersen was right: Ugly ducklings, occasionally, turn into swans. But even more because, if the uncomely babies never do turn handsome or beautiful, great things may befall them, since they won't be subject to the distractions of personal beauty. Maintaining and enhancing one's mirror image can be a full-time job, by definition a superficial one, with a tragic ending brought about by the passage of time. Inevitably, surface beauty fades.

Think of the ostensibly ill-favored, however, who, by their deeds, have become veritable gods: Andersen himself, Eleanor Roosevelt, Abraham Lincoln, to name just three of my favorites. Variously, their faces project sensitivity, empathy, hard-earned wisdom, a quietly unshakable firmness of purpose--elements of temperament that can transform the world.

© 2007 Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on October 8, 2007.

Fall for Dance Festival / New York City Center, NYC / September 26 - October 6, 2007

If you're already a dance fan, you're still welcome to come (after all, seasoned viewers really appreciate the bargain rate of $10 for any seat in New York's huge, prestigious City Center). Bear in mind though, that the annual Fall for Dance Festival was not designed primarily for you. The brainchild of Arlene Shuler, it's meant to seduce newbies, with its program of succinct takes from four or five different companies in its run of ten showings of six different programs. These programs are artfully contrived to encompass such a wide variety of dance genres--Twyla Tharp rubbing eloquent shoulders with the Kirov Ballet, postmodernists abutting practitioners of traditional Indian dance--that only a cultural clod could come away without discovering something to like. Now in its fourth year, with other cities wisely copycatting the idea (among them, Orange County Performing Artscenter, OCT 11-14), Fall for Dance has statistics to prove its significant contribution to increasing the audience for an art that could deliver ecstasy to far more people than it's reaching.

Opening night's first image was breathtaking: a bare-chested Michael Trusnovic--tall, strikingly pale and fair-haired, with pecs out of an ad for a gym--leapt forward on an imaginary diagonal route, one leg piercing the air before him, the other tucked up under him like a bird's in flight, his gaze directed to a faraway, perhaps heavenly, horizon. Just seconds later, five buddies charged after him, full of the same muscular grace. A trio of women arrives eventually to soften and deepen their force, adding piquancy and tenderness, but this piece, Arden Court, remains a guys' dance in which Paul Taylor emphasizes his conviction that the human animal morphs with ease between angel and gargoyle, beautiful and damned.

Have I mentioned the choreography's musical savvy? Have I mentioned its intricate but always accessible structure, which has a divine logic to it, yet is full of surprises? No? Well, next time. Meanwhile, much praise is due to the dancers, who performed as if this were the occasion they'd be remembered by forever.

Ekaterina Kondaurova and Islom Baimuradov of the Kirov Ballet of the Mariinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg, Russia. Photo by Nina Alovert.

The middle of the program comprised a pair of small pieces: Middle Duet, by Alexei Ratmansky, who heads the Bolshoi Ballet, and a solo, Varnam, by the Indian dancer Shantala Shivalinggappa.

The Ratmansky, seen earlier in New York with City Ballet performers, has its partners practically welded to each other, while the woman puts the famous Russian-School placement and fluidity at the service of postmodern impulses. The man supports her antics with a submissive cooperation that evolves into understandable sullenness. Ratmansky's choreography is both deft and witty concerning the manners and methods of ballet partnering. The Kirov Ballet duo that performed it, Ekaterina Kondaurova and Islom Baimuradov, were likewise deft and very charming.

In her pleated-skirt-over-trousers outfit of raspberry and gold, Shantala Shivalinggappa, choreographer and dancer for her offering, looked like a decorative figurine. She is a beautiful young woman who possesses, in the highest degree, the animated face, "speaking" eyes, and extraordinarily articulate fingers of her trade. When she works in place, telling her story in traditional mudras, her body takes on a wonderful sculptural quality, yet I found her too squarely tied to the beat of the onstage musicians. While her technical prowess was striking, she seemed--as if her imagination remains unkindled--to lack the quality we dare to call soul.

Of course it was a pleasure to see Twyla Tharp's 1973 Deuce Coupe again and, you'd think, an inspired idea to cast it with Juilliard students, who combine crossover dance skills with the raw appeal of youth. Yet this production, staged by William Whitener, who was in the original version commissioned by the Joffrey Ballet, suggested that today's youth, though technically glib, may not "get" the awkward passions of yesteryear's young. What can the Beach Boys' songs evoke in teens and twenty-somethings reared on rap?

The Juilliard dancers gave the piece a respectable rendition--one that at least conveyed the idea of it, if not its flesh and blood. Several of the male solos registered as tours de force, while Mary Ellen Beaudreau rightly aimed for the persistent calm of the girl in white who threads her way through the raucous, often stoned crowd, executing steps from the classical ballet lexicon in alphabetical order.

In the last three and a half decades, Tharp has gone on to create dances that are even more savvy than this one, but not one that's as innocent, poignant, or so much fun. Like Jerome Robbins's 1944 Fancy Free, Deuce Coupe comes from a time that will never return, and it's good to be reminded of it.

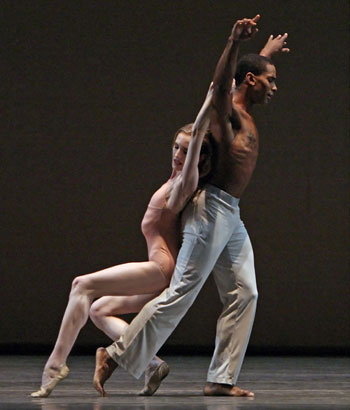

For me, three of the five items on the October 4th program vied for Best in Show: the plangent duet from Christopher Wheeldon's After the Rain, sensitively danced by Wendy Whelan and Craig Hall; Trisha Brown's Spanish Dance, a line dance for five women that delivers this choreographer's intelligence and wit in a nutshell; and Noche Flamenca, whose Soledad Barrio invariably takes you to the dark places of the soul and strips you of your protective blindfold.

Wendy Whelan and Craig Hall in Christopher Wheeldon's After the Rain. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

Apart from the dancing itself, the most thrilling thing about the Fall for Dance performances was the audience, which had the vivacity of a bunch of high school students. The full houses applauded every item (even the abstruse ones) enthusiastically, cheered their favorites, and filled the pauses between numbers with animated chatter. It was a privilege to be in their midst. Their openness to joy--indeed, expectation of it--was contagious. I just hope, as do the Fall for Dance producers, that some of them will turn into veterans like the colleague I ran into in the lobby and asked, teasing, "So, are you going to fall for dance?" "I fell for dance a long time ago," he replied, "and never got up."

© VoiceofDance.com 2007

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on October 3, 2007.

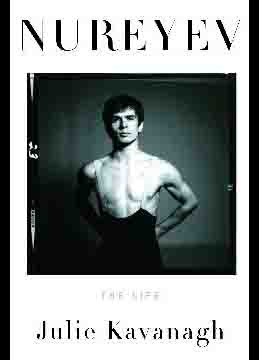

The book jacket for "Nureyev: The Life" by Julie Kavanagh is pictured in this undated handout image. Source: Pantheon/Schocken Books via Bloomberg News

Oct. 3 (Bloomberg) -- At its height, Rudolf Nureyev's dancing combined the feral power and beauty of his movement with a passionate, volatile temperament. He transformed his raw gifts into a sleek professional style -- part Russian, part European - -without ever giving up his spontaneity. Wildly flamboyant and deeply soulful by turns, he seemed to live the characters he portrayed as if they were his alter egos.

Julie Kavanagh's ``Nureyev: The Life'' relates in great detail the saga of a boy born of Tatar stock in 1938, who achieved fame equal to Nijinsky's and died, after a long battle with AIDS, in 1993.

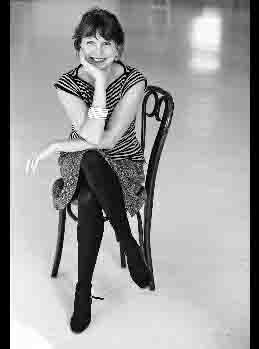

Julie Kavanagh, author of "Nureyev: The Life," poses on Jan. 23, 2007. Photographer: Arthur Elgort. Source: Pantheon/Schocken Books via Bloomberg News

Her obsession with minutiae sometimes undermines the drama of Nureyev's life, though the tale of his defection to the West is told with energy. To her credit, Kavanagh makes it clear that Nureyev was born to dance to his own tune and that, despite the damage he did to others and some dire consequences for himself, he was an incomparable artist who made the world a more thrilling place.

As a child during World War II, Nureyev, his mother and three sisters (his father was nearly always away on military duties), led a life of bleak deprivation near the provincial town of Ufa. When he was 7, his mother snuck her four children into a ballet performance on a single ticket. By the time the final curtain fell, Nureyev had committed himself heart and soul to dance.

His innate gift for dancing -- spirited, musical, enhanced by his charismatic personality -- had surfaced early on in kindergarten folk dancing. His innate rebelliousness appeared early, too, as did his ability to use people to further his career.

Insatiable Hunger for Art

From adolescence on, Nureyev demonstrated an insatiable hunger for the arts -- dance, of course, which he pursued with a future saint's sense of vocation -- but also music, painting, theater, books and architecture. He was equally curious about people from foreign milieus, forging acquaintances the Soviet system would strictly forbid.

In the course of his life, Nureyev had a half-dozen nearly impossible dreams. He wanted -- indeed, expected -- to be recognized as the greatest dancer in the world. Even when age and illness had diminished his incomparable technique, ecstatic viewers thought he was just that.

He was determined to train at St. Petersburg's celebrated Vaganova Academy, which fed the Kirov Ballet, to him the epitome of aristocratic elegance. Against all odds, he managed do so, worked fanatically and became one of the company's best hopes.

Spontaneous Defection

Then he needed to escape from the repression of the Soviet system, aggravated in his case by his homosexuality and the conservative rigidity of the Kirov at that time. His dramatic defection -- long dreamed of but spontaneously achieved in a Paris airport -- came in 1961 and led to his international career.

Nureyev also yearned to absorb the cool perfection of the Danish legend Erik Bruhn. Polar opposites in temperament and style, they did indeed influence each other's dancing and conducted an intense and tempestuous love affair to boot.

He danced with Margot Fonteyn, the Royal Ballet's prima ballerina, an adored exemplar of radiant lyricism and almost 20 years his senior. Their partnership became legendary.

Only one wish remained unfulfilled: He longed to dance for Balanchine, a pairing that failed because Balanchine was certain his choreography would be undermined by superstars.

All in all, Nureyev did better for himself than most mortals.

``Nureyev: The Life'' is published by Pantheon Books in the U.S. and by Fig Tree Press in the U.K. (782 pages, $37.50, 25 pounds).

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary