Seeing Things: August 2007 Archives

This article originally appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on August 27, 2007.

Nureyev: The Russian Years / PBS "Great Performances" / August 29, 2007

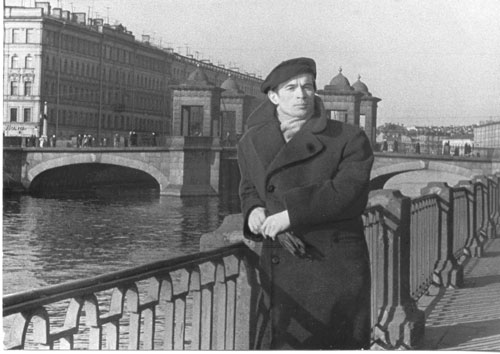

Rudolph Nureyev. Photo courtesy Thirteen/WNET New York.

Rudolph Nureyev (1938-1993), the Tatar ballet dancer, was a phenomenon before America and the world at large ever heard of him. Now there's a TV documentary supporting that position. Nureyev: The Russian Years, a joint project of WNET and the BBC, has its American premiere August 29 in the PBS "Great Performances" series. Written and produced by John Bridcut, it chronicles the earliest segment of the dancer's career through the immediate period following his dramatic defection from the Soviet Union in 1961. And of course it exalts Nureyev as the exotic, feral, passionate performer he was.

True, Nureyev's saga has been endlessly--sometimes fancifully--documented. This program escapes redundancy because it offers on-camera interviews with the dancer's colleagues and friends who could not speak freely before the Soviet regime collapsed and footage of Nureyev's dancing in his youth not accessible in the West until now.

Much of this early footage was shot by Teja Kremke, an East German ballet student who became Nureyev's lover when they were both young. (Julie Kavanagh, whose exhaustive biography, Nureyev: The Life, will be published by Pantheon next month, tracked it down, and served as consultant to Bridcut's project.) Kremke's amateur film, showing the unseasoned Nureyev's ability to defy gravity and conquer space--with phenomenal strength, coordination, grace, and a very individual musicality--proves that his unique talent and dynamic temperament were evident from the start.

Nureyev grew up in rural surroundings without luxury of any kind, except for, it's implied, his mother's love. As a boy, he liked to watch trains, which he found romantic. He was, actually, born on a train, which later seemed prophetic of his adult life--its drama and its shifting landscape.

When he saw his first ballet at the age of 7 in the provincial town of Ufa, it was love at first sight. Ostensibly he declared, "That's all I'm going to do--dance!" Living "in the sticks" as he did, with no economic resources and a father who insisted that dancing was an unsuitable profession for his son, Nureyev could hardly have fulfilled his near-impossible dream without his innate avidity and persistence.

He did menial work to pay for his childhood lessons in folk dancing, then had some rudimentary ballet training and local performing experience. His aim for the future, though, was nothing less than to attend the ballet academy in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), whose best students graduated into the legendary Kirov Ballet. It was the alma mater of the likes of Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina, George Balanchine, Alexandra Danilova, Natalia Makarova, and Mikhail Baryshnikov.

He finally succeeded and, in 1955, he fell in love again, with the city of Leningrad and the Kirov Ballet and its academy. He was 17, and thus a late starter at an institution geared to molding children into professionals. Nevertheless, he declared to his far more experienced peers, "I will be the number one dancer in the world." Modesty was not in his rep--perhaps he couldn't afford it--but he worked fanatically to develop his skills.

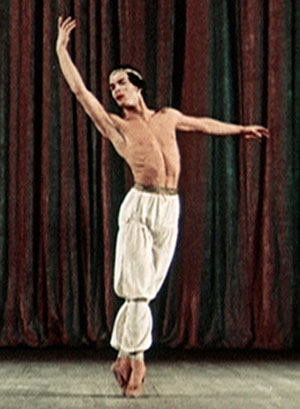

The documentary offers the earliest known film of Nureyev dancing--at 20, at a Moscow student competition in a solo from Le Corsaire. Subsequently included in a film that was shown widely in Russia, it was the start of his fame in his motherland. In his final year at the Kirov's school, however, the company did not offer him a place, though its competitor, Moscow's Bolshoi Ballet, invited him to sign on as a soloist. At the last minute, the formidable Kirov ballerina Natalia Dudinskaya, nearing the end of her stage career, said, "Why don't you stay here and dance with me?" (Today, this May-December coupling seems to prophesy the celebrated partnership Nureyev would form with England's prima ballerina assoluta, Margot Fonteyn.)

Rudolf Nureyev in Le Corsaire at a student competition in 1958. Photo courtesy of Thirteen/WNET New York.

Once an official member of the Kirov, Nureyev went to live with his former teacher, the celebrated Alexander Pushkin, where he was pampered and probably slept with Pushkin's wife, violating a primal law of hospitality. At the theater, too, he was thought of as a troublemaker: for his insistence on pursuing a wide cultural horizon where insularity was the rule and seemingly small incidents as well, such as his refusing mid-performance one night to continue in the loose trousers assigned to the male dancers and insisting on the Western fashion of form-fitting tights. He was a rebel in the land of restriction.

The show records his partnership at the Kirov with the ballerina Ninel Kurgapkina, now in her late seventies and the most vivacious figure in the documentary after its hero. Indeed, the circle of Nureyev's associates interviewed here gives a marvelous impression of the best aspects of the Russian spirit--courage, humor, and an unflagging awareness of life's richness, even in daunting circumstances.

In 1961, the Kirov decided to exclude Nureyev from its planned tour to Paris because of the rash independence of his personality. But Janine Ringuet, an assistant to the French presenters, having seen him dance, had her superiors insist that he appear in France. This was Nureyev's opportunity to defect and, despite the obvious dangers, he took it.

The documentary contends that Kremke had planted the idea in Nureyev's mind that a talent like his must take the whole world as its stage. If so, it surely accorded with Nureyev's sense of what his gifts deserved. It's equally true that his defiant temperament and the fact that he was gay made him a natural target for repressive authority, so that his future in Russian seemed precarious.

At any rate, Nureyev danced in Paris, to a tumultuous reception. Then, as the company assembled at Le Bourget airport, Nureyev was informed that (for some trumped up reason) he was not to go on to London, the next leg of the tour, but to return to Russia. The dancer's reaction: "I am a dead man." Witnesses disagree about what happened next. The French dancer and choreographer Pierre Lacotte, who had befriended Nureyev in Paris, recounts his version of the event, which culminates in Nureyev's hurling himself into the arms of the French police, shouting, "I want to be free." Granted asylum, he hid out for a time in Paris without any means of practicing (the equivalent of a prison sentence for a dancer).

Eventually he joined the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas, while the KGB, which had long had its eye on him, tried every device possible to retrieve the man they called a traitor. Nureyev managed to evade them and went on to three decades of the glories we are most familiar with: the celebrated partnership with Fonteyn, whom he called his soul mate; the association with the Denmark's Erik Bruhn, a quintessential danseur noble, ice to Nureyev's fire; performances worldwide that received unbridled accolades; work as an artistic director and choreographer.

Nevertheless, as the Danes say, Nureyev's life was not a dance on roses. His close friends in Russia were often held under suspicion and Kremke died at 37 in "unexplained circumstances." The Soviet government prevented Nureyev from returning to visit his family until his mother was dying, and when, much later, Nureyev finally danced again on the Kirov stage, he was already dying of AIDS.

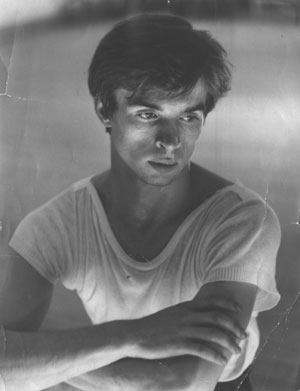

Rudolph Nureyev. Photo courtesy of Thirteen/WNET New York.

His choreography alone would not have won him a place in the history books. Mostly, he created his own versions of revered nineteenth-century classics, choreographing perverse solos for himself, solos made of phrases that twisted the classical vocabulary against its own grain. Purists found this ploy exasperating, but Nureyev was determined to show off his mastery of the difficult and to make the hero of these traditional pieces that favored the ballerina equally important.

He felt compelled to go on performing long after his technique had conspicuously declined and his abilities were finally scuttled by illness. By his last years on stage, he was dancing solely on his charisma and his legend. Yet the general public was still roaring its approval and adoration. Just as at the beginning, people recognized a hero when they saw one.

Nureyev: The Russian Years is conventionally structured. It's also disconcertingly patched together, with scenes never recorded--like Nureyev's first sight of a ballet--"reconstructed" with latter-day participants or showing Nureyev's appearance in a ballet to accompany voice-over narrative of his life. What's more, these devices aren't employed with any great skill or imagination. The unique worth of this venture lies in the archival footage and the interviews with people close to Nureyev who were not free to speak openly of him during the Soviet era. And Nureyev himself, with his wicked intelligence, rebelliousness, and ardor, makes one of the most compelling talking heads in the bioflick genre. Even when he's not dancing, he's a star.

© VoiceofDance.com 2007. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on August 21, 2007.

Mark Morris Dance Group, Mozart Dances / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / August 15-18, 2007

Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris's Mozart Dances. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

I saw (and wrote about) the world premiere of Mark Morris's Mozart Dances a year ago at the New York State Theater, when it was presented as part of Lincoln Center's annual Mostly Mozart Festival. This year the Festival gave it four encore performances, August 15-18, on the same stage, and I felt I was seeing deeper and deeper into its immaculate architecture and enigmatic, stirring emotions.

Defying possible monotony, Morris set all three parts of his dance to piano compositions: "Eleven" to the Piano Concerto No. 11 in F major; "Double" to the Sonata in D Major for Two Pianos; "Twenty-seven" to the Piano Concerto No. 27 in B-flat major. Like Balanchine, who frequently took the names of his ballets from their music, Morris made his own titles as blunt as could be. This is a canny device for refusing to tell the audience what a ballet is "about," thus relying upon the individual viewer to listen and watch keenly, activating his or her imagination.

As at the dance's New York performances last summer, Emanuel Ax was the pianist for the concerti, Yoko Nozaki seconded him for the Sonata, and Louis Langrée led the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra. I haven't heard music played for dancing as sensitively as this since the pianist Garrick Ohlsson collaborated with Annabelle Gamson, a matchless interpreter of Isadora Duncan's work.

Call Mozart Dances abstract if you will, but its first two segments are extraordinarily rich in subtext. As with Balanchine's Serenade, there is no "story" of the sort that might neatly be pinned down in a program note. Still, the choreography continually hints at character, situation, even fragments of plot--all to be interpreted "personally."

"Eleven" opens with a horizontal lineup of seven men who vanish almost before their presence has registered. Their presence simply notifies you that they'll be back eventually. The rest of the dance belongs to eight women. Lauren Grant, a small woman crowned with blond curls, is the protagonist. She combines a lush sculptural quality with clarity and astounding projection, qualities that have made her one of the Mark Morris Dance Group's greatest dancers and greatest stars.

Lauren Grant. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

The others, each distinguished in her own right, form a chorus who witness and, to a point, empathize with Grant's unnamed experiences, passions, and sufferings. The "to a point" reservation is critical because Morris makes it very clear that, when it comes down to it, each of us is alone.

This section introduces the gestures and movement motifs that the entire piece will use again and again, each repetition, at least in the first two parts of the triptych, showing us the move at a new angle or taking on fresh meaning from a new context. Instances that burn themselves into your brain: Grant, at the opening, folding one arm up toward her heart; the other women clustering at the side of the stage, looking skyward as if mildly examining the weather; dancers rooted in place, dynamic in their stillness, their backs toward the audience, arms akimbo, hands overlapping at the vulnerable spot where the head joins the neck; and a sudden fall--this becomes the section's curtain line--arms and legs splayed and angled as if the body had been thrown from a motorcycle speeding heedlessly over rocky terrain.

Mark Morris Dance Group in Morris's Mozart Dances. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

"Double" features the eight men we glimpsed in "Eleven." To me, Joe Bowie, in an inky frock coat modified for dancing and black biker shorts, represents Mozart, teaching the others, common men, whatever can be taught about art. One of them, Noah Vinson--looking innocent and vulnerable with his boyish build and childlike face--seems to be his special protégé.

But then, as the men bond in an exquisitely inventive circle dance, Vinson, both arms angled up to his heart, fists clenched in anguish, tells us he is going to die. As the women did with Grant, the band of brothers does its best to succor and protect him, but falls away when nothing prevails, leaving Vinson pathetically lost in a world devoid of landmarks. Bowie remains constant, though, like a father with a doomed son, no longer instructing but simply being there.

Suddenly, like an astonishing vision, the women appear, wearing limp gauzy skirts that sweep the floor, an acknowledgement that Vinson is beyond the help of his fellow man and needs a circle of angels to escort him from this life to the next. Yet a moment later, cued by a shift in the music, all is well again, the dancing joyful and robust, Vinson's tragic fate magically rescinded. The dance as a whole captures the spirit of certain Mozart operas and is one of Morris's finest achievements to date.

In "Twenty-seven," the third and final segment of Mozart Dances, men and women meet in equal numbers, in bright sunlight, so to speak, suddenly shorn of mystery. They seem to represent the concepts of society as a solid whole and the fleeting formation of couples within it. As is true of Balanchine's Jewels, comprising "Emeralds," "Rubies," and "Diamonds," the last segment of the trilogy is weaker than the two that preceded it. In the case of the Morris piece, it's far weaker.

The repetition of all the dance's basic gestures, which felt so organic before, now seems forced and thus grows tiresome. Brief solos for the individual dancers look obligatory--the fifteen seconds in the sun that is undeniably each one's due--though a few of them, like the one for Elisa Clark, a plain-faced woman who's the epitome of grace, are particularly beautiful and/or surprising.

In a later passage, there are some amazing man-woman lifts--a rare device for Morris. Unlike the hoist and triumphant sculptural pose typical of classical ballet, these lifts are all flow. Spilling through the space, they're counterbalanced by falls into stillness that eloquently suggest, as they have throughout the dance, that this is what we all come to. Even so, the ideas of an entire populace finally assembled, with friendly small clusters within it, don't contain much specific or profound feeling this time, though they are familiar Morris concerns. Subtext is slender or absent entirely here, while there's far too much footage of cheerful-natives-frolicking-on-the-village-green. Of course Morris might say, "The music made me."

Martin Pakledinaz designed the beautiful, witty black and white costumes. James F. Ingalls provided inexplicably routine lighting. The three overbold backdrops of giant paintbrush strokes, the work of Howard Hodgkin, stubbornly refuse any connection to the music or the dancing.

I saw the performance on the 16th, which was televised on PBS' "Live From Lincoln Center" and seen by millions of viewers -- not just the 2700-plus that the State Theater holds -- and no doubt recorded for an afterlife by many of them.

It was intriguing to witness, live, an event that, under ordinary circumstances, would be ephemeral. The fact that performance exists, as Marcia B. Siegel puts it, at the vanishing point, is a significant part of its compelling fascination. I realized as I was watching, though, that this performance, in its televised version, would give Mozart Dances a solid place in dance history, though the video is only a reproduction.

What I missed, and the television audience saw, was Sam Waterston as host and a pre-recorded intermission homage to the late Beverly Sills, who regularly filled that role with her inimitable vivacity. I could catch up with the recorded version, but, unless I need it for study purposes, I probably won't, even though Waterson is my heartthrob.

© VoiceofDance.com 2007. Reprinted with permission.

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary