Seeing Things: July 2007 Archives

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on July 26, 2007.

July 26 (Bloomberg) -- Thoreau was right when he wrote that urban life threatens to do us in. Frederic Flamand, director of the Ballet National de Marseille, tackles this theme in ``Metapolis II,'' which opened last night at the New York State Theater as part of the Lincoln Center Festival.

A collaboration with Pritzker Prize-winning architect Zaha Hadid, the ballet creates a maelstrom of elements that dehumanize our society: frenetic pace, crowding, an impersonal environment. At the same time, it proposes that moments of empathy and tenderness, even an occasional return to the scale in which man is the measure of all things, are still possible.

The hubbub of modern life is represented by a heady mix of media. Projections of fast-moving, crazily angled cityscapes -- jangly street life, cars traveling endlessly through claustrophobic tunnels, buildings imploding -- are juxtaposed with dancers interacting with real-time images of themselves.

Hadid contributed three zigzagging aluminum bridges that the performers manipulate into changing configurations, standing, lying, crawling and sliding on them, even popping in and out of circular cutouts in their surfaces. Her futuristic costumes, severe and gaudily playful by turns, reveal the consoling glow of flesh. This helps us think of the dancing figures as real people, at once beautiful and vulnerable, rather than as automatons.

Disembodied Voices

The collaged score involves a violin played live, occasionally plaintively, most often against percussive thrumming and static or disembodied voices that seem to lack a common language.

The choreography is the weakest link in the mix. ``Metapolis II'' is a makeover of the original ``Metapolis,'' created in 2000 with a troupe specializing in experimental dance. In transferring the piece to the Ballet National de Marseille, Flamand reworked it for classically trained performers, combining traditional ballet steps with a generic postmodern style. He can't make a coherent dance phrase, though, so the movement registers as an endless series of gestures.

About three-quarters of the way through the piece, passages we'd recognize as love duets under more auspicious circumstances overtake the disaffected proceedings. Still, even these occasions for intimacy have no subtle moments and no climaxes.

Flamand's greatest flaw -- an odd one for a man who has collaborated with several respected architects -- is a gravely deficient command of structure. The choreography for ``Metapolis II'' is just a restless string of happenings. One brief scene succeeds another, but as a whole the ballet goes nowhere and takes far too long to get there.

Shen Wei

Sheathed in pale gray pajama-like outfits, faces chalked white, the dozen dancers in Shen Wei's radical version of the Beijing opera ``Second Visit to the Empress'' look like ghosts. Their ultra-fluid movement, adamantly abstract, is done in groups, as if they've been shorn of individual identity.

By contrast, the three leading singers in this political melodrama -- translated in terse supertitles at Lincoln Center's New York State Theater -- are costumed in wildly imaginative shapes, textures and color schemes, bathed in golden light and initially enshrined like saints. Their voices pour out from their stillness, powerful and evocative.

The piece, which originated some 300 years ago, became a staple of the Beijing Opera repertory. Shen loved the opera and wanted to give it new life as he pursued his career as a choreographer and visual artist in the U.S.

Adding Dance

In Shen's version, presented during the final week of the Lincoln Center Festival, the score has been cut and edited to make it palatable to today's audience. Shen intended to beef up the dynamics by adding dancing to what was originally an excruciatingly static presentation, the three main characters placed in an immobile row and left to get on with their vocalizing.

Shen's strongest gift is for creating visual imagery, however, not movement. In this production, the 16-member Chinese- instrument orchestra of winds, strings and percussion churns up far more energy and emotion than the dancing wraiths. And the diva, Zhang Jing, bends and sways in antiphonal curving shapes, looking for all the world as if she assiduously took dance class several times a week.

``Metapolis II'' will be repeated tonight and tomorrow at the New York State Theater, Lincoln Center. ``Second Visit to the Empress'' will be repeated July 28 and 29 at the New York State Theater, Lincoln Center. Information: +1-212-721-6500 or http://www.lincolncenter.org.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on July 17, 2007.

July 17 (Bloomberg) -- Dressed in rakish, mismatched bits of theatrical costume, six feisty dancers evoke a ragtag traveling circus onstage and off. They're down on their luck yet plucky, lacking the talent to match their big dreams.

This is ``B'zyrk,'' one of the new-to-New York pieces in the opening-night program of Pilobolus, the company that will be cavorting at the Joyce Theater in Chelsea through Aug. 11.

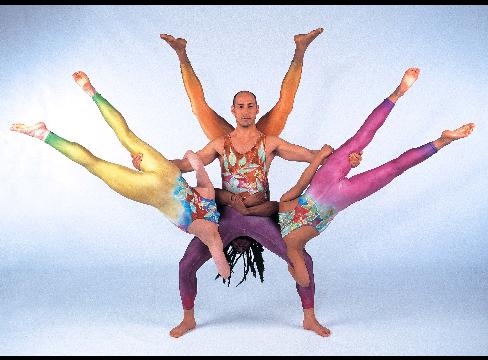

As is typical of a Pilobolus creation, the collaborative choreography by Jonathan Wolken and six others features gymnastics, feats of balance and timing, horsing around and the merging of bodies into strange shape-shifting organisms. One three-body combination whirls along the floor like tumbleweed.

Wolken and his crew try hard to evoke both the bitter weariness of second-rate performers worn down by endless one- night stands and their vision of themselves as beautiful and strong, altogether worthy of applause and fame. But the results are more trite than unique and genuine, and the physical marvels are too crude to express the poignant atmosphere the choreographers mean to create.

While the music is compiled from five sources, the costumes are from a single hand, that of the ever-ebullient Liz Prince. The performers, like most Piloboli, are endearing, especially Manelich Minniefee and Renee Jaworski.

Memorial Dance

A second piece receiving its local premiere was ``Persistence of Memory'' by Michael Tracy, with assistance from Minniefee, Annika Sheaff and Edwin Olvera. As performed by Minniefee and Sheaff, it's a light, sweet duet that was commissioned as a memorial to a woman who died too young. It shows the woman in a variety of moods, as if she were a real personality, not an object of veneration simply because her life was cut short.

As with ``B'zyrk,'' the feelings the dance attempts to evoke are essentially at odds with the typical Pilobolus vocabulary. Here, though, there are a few moments that gel. Early on, for example, the lithe woman, dressed in pale chiffon with her auburn hair unbound, does a backbend all the way to the floor, and the man crawls into the cave her body has shaped.

Most impressively, the woman is quietly but constantly shown to equal the man in physical strength, bearing his body just as calmly and beautifully as he does hers. I could imagine the dance being done to great acclaim at a feminist rally. Though it's too simplistic to be worth seeing twice, it's worth seeing once.

Honed Bodies

Pilobolus is one of the most popular dance troupes around. Its current monthlong engagement at the Joyce has become an annual affair, and the group tours worldwide. The highbrow dance audience turns up its nose at Pilobolus -- ``You call that dancing?'' -- but the general public loves it.

Why?

It's nonthreatening like Cirque du Soleil, and it's immediately accessible; there are none of the half-hidden meanings of Balanchine's ``Serenade'' or Graham's ``Errand Into the Maze.'' It can also be funny, though the fun is usually sophomoric.

Pilobolus can be sensuous, too. The dancers' magnificently honed bodies are sheathed in bright, high-sheen unitards or cannily designed rags that advertise every gorgeous contour -- or just left as close to nude as the police permit. And the Kama Sutra-style intertwining of the bodies is something even people who can live without dance will appreciate mightily.

Some of Pilobolus's early pieces had more ambiguity and sophistication, plus provocative investigations of the grotesque. Perhaps today's public prefers simply to be entertained.

Pilobolus is at the Joyce Theater, 175 Eighth Ave. (at 19th Street), through Aug. 11. Information: +1-212-242-0800 or http://www.joyce.org.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on June 28, 2007.

Mikhail Baryshnikov and Hell's Kitchen Dance / Howard Gilman Performance Space, Baryshnikov Arts Center, NYC / June 22-24, 2007

Dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov. Photo by Olivier Simola.

Tragically, classical ballet dancers are athletically over the hill in their thirties. That leaves decades of life to be used constructively. Some artists--like the legendary Alicia Alonso, Margot Fonteyn, and Rudolf Nureyev--insisted upon performing until the last gasp, pathetic yet still gripping. (Frayed genius is still genius.) Some take up related work--leading companies, teaching. A few (though usually not the superstars) move on to entirely different professions. The 59-year-old Mikhail Baryshnikov, whose name is as likely to be indelible in the history books as Nijinsky's, found eloquent ways to dance once ballet's virtuoso jumps, leaps, and turns were beyond him, notably in the postmodern mode with his White Oak Dance Project (1990-2002).

The year 2005 marked the opening of the long-awaited Baryshnikov Arts Center, way west on 37th Street in Manhattan, to foster the development and collaboration of artists in multiple disciplines. June 22-24, in BAC's Howard Gilman Performance Space, a black box theater that seats 180 when you pack 'em in real tight, Baryshnikov showed New Yorkers Hell's Kitchen Dance (named after BAC's nabe), which has been touring the country. The two commissioned works on the bill, Donna Uchizono's Leap to Tall and Aszure Barton's Come In, both created in 2006, encompass the present-day skills of the superstar, dancing with superb, mostly youngish performers.

Today, Baryshnikov is naturally weaker in the departments that middle age erodes: strength, speed, and elasticity. Those who thrilled to him in his physical prime will probably be saddened by what they see today. Yet he remains a phenomenon.

He has retained a certain amount of his legendary physical dexterity. Though muted, it still represents the Platonic ideals of classical dancing. When he's standing in place, his posture is too taut, almost militaristic, as if defiantly confronting ruin. Once he starts moving, though, his joints look remarkably supple.

His theatrical intensity is undiminished. The only performer I've ever seen upstage him was the venerable Merce Cunningham, who, standing in the background, grasping a barre for support part of the time as he sketched a move or two, managed to be even more compelling than Baryshnikov dancing full-out in the foreground.

The killer charisma is intact. But it has evolved from a winning boyishness to the allure of a mature man, face lined by experience, who is piercingly clear-eyed about life and the passage of time. His keen intelligence is more evident than ever.

And then there was the choreography, better than average, certainly, yet nothing you'd rush to see were such a hero not at its center.

Uchizono's Leap to Tall (what the title might mean escapes me) is a trio for Baryshnikov and two women, Hristoula Harakas and Jodi Melnick, who is wonderful and mature enough to have copped her Bessie award for "sustained achievement in dance" half a dozen years ago.

The design of the dance is tasteful and intelligent, beginning with the two women upstage, delicately edging their way across the space with tiny pivots of the feet, while Baryshnikov lurks quiescent, barely visible in the shadowy foreground. But serviceable craftsmanship alone--largely presenting Baryshnikov in inviolably rigid stances that eventually melt into more fluid action--can't create a telling theatrical experience. Clocking in at 31 minutes, the piece feels far too long, its stubbornly enigmatic key gestures repeated too often to keep the viewer's mind curious--or even alert.

The only segments that hit the heart (and are interesting physically, to boot) are the tender and witty takes on male-female partnering. In his heyday, Baryshnikov did his magnificent share of hoisting ballerinas aloft, his strength, impeccable carriage, and ardent chivalry making them look like airborne divinities even when his mouth was full of tutu-tulle. Uchizono's women occasionally return the favor granted to their back-in-the-day sisters. They act like gentle puppeteers, seeming to propel Baryshnikov through steps that recall his triumphant reign as a classical dancer and cradling him with their arms to lift him just a few inches from the floor, as if he were a much-beloved toddler. His cooperation is at once sweet and ironic.

The music, by Michael Floyd and Iva Bittova, follows upbeat percussion with lulling pop-romance.

Mikhail Baryshnikov and Hell's Kitchen Dance in Aszure Barton's Come In. Photo by Nancy J. Parisi.

Aszure Barton's piece, Come In, takes its name from its Elgar-like score by the contemporary Russian composer Vladimir Martynov. Both music and choreography give nostalgia a good name, and Barton's work has far more emotional impact than Uchinozo's.

Against a videotaped landscape panorama evoking Baryshnikov's Russian origins, a populace in simple black clothes seems to confront the past and acknowledge that (pace Proust) it cannot be recaptured. Baryshnikov being the central figure in the piece, the sentiment can be applied specifically to his performing career and his expatriate status. However, the choreographer and the dancers make it universal--resonant for all of us in one way or another.

Two elements engrave themselves in one's recollection of the dance: Baryshnikov's making a simple gesture take on new nuances every time the choreography requires him to repeat it, thus expressing decades of emotion and memory, and the sense of present love for a particular person meshing with abiding love for a place left behind. Perhaps I'm exaggerating the virtues of Barton's piece, but it's the sort of thing to which I'm susceptible.

© VoiceofDance.com 2007. Reprinted with permission.

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary