Seeing Things: April 2007 Archives

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on April 26, 2007.

April 26 (Bloomberg) -- What grand gesture can you make to honor the centenary of an icon's birth? The New York City Ballet is dedicating its spring season, which opened last night at the New York State Theater, to Lincoln Kirstein, co-founder, with George Balanchine, of the company and its prestigious academy, the School of American Ballet.

All this week, the programs will be devoted to 10 Balanchine works that define the choreographer's world-shaking development of classical ballet in the 20th century. They serve as indelible evidence of Kirstein's achievement in luring the choreographer to America and doggedly furthering his career for the decades it can take to make the public appreciate genius.

The ballets are, in order of their creation, ``Apollo,'' ``Concerto Barocco,'' ``The Four Temperaments,'' ``Symphony in C,'' ``Square Dance,'' ``Agon,'' ``Episodes,'' ``Symphony in Three Movements,'' ``Duo Concertant'' and ``Pavane.'' All but the last of them -- which simply provides a role suited to Kyra Nichols, the last ballerina Balanchine developed -- seem to sum up the classical-dance legacy Balanchine absorbed from the past and catapulted into the future.

The sentiment of the occasion is fitting. The pressing question is: How are these works being danced now? There has been plenty of complaint in the past two decades about the NYCB's custodianship of the Balanchine canon. The company's performances have frequently been criticized as slipshod.

On opening night, ``The Four Temperaments'' and ``Agon,'' two of the choreographer's most forward-looking masterworks, looked scrupulously rehearsed, clear and sharp-edged. Apart from some seasoned soloists, though, the dancers often seemed to be speaking a diligently learned foreign language, not their mother tongue. They looked far more at ease in the more conventionally classical ``Symphony in C,'' giving that extraordinary showpiece the unquenchable verve and soulful center it demands.

Subtle Dynamics

The rich, subtle dynamics that characterized NYCB performances when Balanchine himself supervised them were too often absent from the evening's program, as they have been for some time. But a handful of extraordinary talents often made the stage vibrant.

Maria Kowroski, sympathetically partnered by Philip Neal, gave a sublime account of the celebrated adagio movement in ``Symphony in C.'' Sean Suozzi brought surging energy and implicit drama to the Melancholic section of ``The Four Temperaments.'' In ``Agon,'' Teresa Reichlen deployed her elongated, eerily supple body with enormous intelligence and composure, while Wendy Whelan and Albert Evans were eloquent in the central duet, with its deeply strange erotic beauty.

`Pavane'

Oddly, ``Pavane,'' a bagatelle compared to the heftier works on the program, got the most memorable performance. Set to a sinuous Ravel score, this solo for a woman in a diaphanous white dress was danced by Nichols, who will retire at the end of the season after 33 years with the company.

Her movements emanated from a strolling walk laced with simple gestures in which she manipulated a swath of gauzy fabric so that it became a veil, a cloud, a banner -- perhaps an infant that has died. With her musicality and devotion invested in this simple though exquisitely calibrated piece, Nichols brought her lyrical, understated dancing close to perfection.

Even with less than ideal performances, Balanchine's choreography triumphs. In a single evening, it can make much of the dancing one has seen all year irrelevant.

Kirstein Show

Lincoln Kirstein (1907-1996) was a bear of a man with a steel-trap mind, an instinctive feeling for what was next in the arts and the indomitable will and courage needed to bring it into being. While he possessed a general's gift for strategy, he also had a visionary streak that allowed him to accomplish the seemingly impossible. Though giving Balanchine the opportunity to flourish was undoubtedly Kirstein's greatest achievement, from the time he was a Harvard undergraduate, he made significant contributions to the advancement of literature and the visual arts as well.

His formidable presence is captured in an exhibition mounted throughout the State Theater's public spaces. Edward Bigelow, its curator, describes it as a mosaic. Ticket holders strolling past the disparate elements in the half-hour before curtain time or in the intermissions will see that they cohere.

An aerial view of Lincoln Center, informal shots of Kirstein and Balanchine, the two with Peter Martins, who leads the company today, and Kirstein surrounded by a flock of SAB children underline the fact that he built an institution strong enough to outlast its founders.

Even more stirring than the photos demonstrating concrete achievement -- shots of seven decades' worth of ballets that depended on his efforts -- are the portraits of Kirstein as a child and youth. The 4-year-old seated on his pony, sturdy body taut, gaze piercing, presages the man he would become. The shyly affectionate boy in a family portrait taken a few years later, and George Platt Lynes's poetic portrayal of him as a young man, complete the picture.

The New York City Ballet is at the New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, through June 24. Information: +1-212-721-6500; http://www.nycballet.com.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on April 20, 2007.

April 20 (Bloomberg) -- The Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg, Russia, is recognizable at a glance.

The dancers are as flexible as rubber bands and emotionally stretched to the snapping point; the stage patterns are exercises in simple geometry; the lifts acrobatic; the gestures extravagant.

There's nothing soft or subtle in the choreography of Boris Eifman, 60, yet it can be crudely effective. It looks like animated poster art.

The repertory for the troupe's season at the City Center, in New York, features ``The Seagull,'' which had its premiere in St. Petersburg in January. Eifman, who has already co-opted Tolstoy's ``Anna Karenina'' and Dostoevski's ``Brothers Karamazov,'' has now turned to Chekhov.

He has pared the chief characters to four and turned Chekhov's subtle, penetrating tragicomedy into a semi-abstract psychodrama. All desire and anguish, it operates, remorselessly, at fever pitch, with music by Rachmaninoff and Scriabin.

Rather than sticking with Chekhov's world of words (writers and actresses) Eifman has shifted the action to the dance stage. His protagonists are a celebrated ballerina past her prime (Nina Zmievets), her rising-star rival (Maria Abashova) and a pair of male choreographers who represent stultifying tradition (Yuri Smekalov) and the cutting edge (Dmitry Fisher). When not occupied with professional competition and generational conflict, the four tangle themselves, soap-operatically, in personal passions.

Ballet About Me

Eifman, whose self-importance is robust, has declared that the ballet is autobiographical, with him as both the established master and the renegade. But his choreography for ``The Seagull'' represents both modes with nothing more than cliches.

Many passages are just peculiar. To indicate male-male confrontation, one guy literally walks up the other's body. For lovemaking, a man manipulates a woman's body as if he aimed to turn her inside out. A gratuitous insert of hip-hop dance just confirms that classically trained dancers haven't got the moxie for these moves.

The most truthful -- and unflamboyant -- scene in the ballet has the reigning choreographer confronted in a dimly lit studio by his assembled dancers. They form a living wall facing him, stony-faced, then stalk him in a circle, as if demanding to be brought to life in new and wonderful ways.

Other choreographers have described the terror of that situation in words. Eifman managed to realize it choreographically. It's the one autobiographical element in the piece that inspires belief.

Pink Floyd

The company is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year, and its first night at the City Center was a tasting menu of excerpts from key Eifman works. It included the soft-porn duet ``Double Voice,'' to rock music by Pink Floyd, with which Eifman defied the repressive Soviet authorities in 1977. To American dance fans, bred in a more permissive climate, the piece would have seemed behind the times in its day; 30 years after the fact, its naivete is truly embarrassing.

The program opened with the world premiere of the first item in the troupe's repertory created by a choreographer other than Eifman: ``Cassandra,'' by the 28-year-old, Moscow-based Nikita Dmitrievsky.

The young choreographer is a chip off the old block. Using a Gustav Holst score like movie music, Dmitrievsky provides characters and narrative taken from mythology and history in their heroic modes (the doomed Greek prophetess, the fall of Troy), stage patterning that might have been plotted on graph paper, and a dance vocabulary of semaphored gestures meant to express extreme states of grief and rage. Somehow, though, the piece is not as over the top as Eifman's usual product (nor anywhere near as powerful as Martha Graham's 1958 ``Clytemnestra''). It's actually too tame.

The Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg continues at the New York City Center, West 55th Street, between Sixth and Seventh avenues, through April 29. Information: +1-212-581-1212 or http://www.nycitycenter.org.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Three-quarters of a year ago, struck by an image, I wrote about a dancer whose history was essentially unknown. Here is the image--

Weegee

Ballerina Marina Franca in her peacock costume, April 18, 1941

Gelatin silver print

© Weegee / International Center of Photography

--and here is the essay. A brief passage in it now seems prophetic: "Contemplating this lady in her outlandish white costume--all shimmer and froth--we wonder: Who is she? How did she arrive at this time and place? This peculiar destiny? What does her "performance" consist of? Is she, perhaps, a reluctant collaborator in her work?"

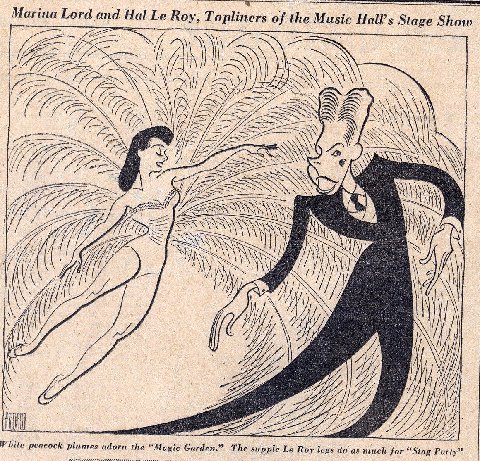

A couple of seasons after the essay appeared, I received an e-mail from Marc Salz, a Philadelphia-based painter in his late fifties, who identified himself as the dancer's son. Since then, through the instantly informative yet strangely remote means of e-mail, he has filled in Marina Franca's story. He also provided me with my first sight of Al Hirschfeld's dashing image of her. Featuring the same outré peacock costume that caught Weegee's eye, it recorded Franca's appearance in the stage show at New York's most extravagant picture palace, Radio City Music Hall.

© AL HIRSCHFELD. Reproduced by arrangement with Hirschfeld's exclusive representative, THE MARGO FEIDEN GALLERIES LTD., NEW YORK. WWW.ALHIRSCHFELD.COM

Marina Franca, Salz relates, was known as Marina Lord at the time of the Radio City gig. Her real name was Wilhelmina Roothooft. She was born in Amsterdam in 1917. In her mid-teens, she decamped for Paris to train for a career in classical dance with the great Russian émigrés who had themselves relocated there. She studied first--in 1932--with Alexander Volinine, then made her debut in 1934 at the academy run by Lubov Egorova. In the late thirties, she studied with Olga Preobrajenska, where Léonide Massine discovered her and introduced her to the Ballet Russe.

The outbreak of World War II abruptly ended Franca's 1938-1939 stint with the Ballet Russe. Salz explains the situation this way: "My mother was separated from her family (her mother and her younger brother, Edmond, in Holland, and her elder brother, Jan, who was in hiding in France). Her father had died earlier, when she was thirteen. She had been sending her mother money for support, she told me, but was otherwise cut off from communication with her family by the Nazi Occupation.

"She left for America, where her career choices were based on her own survival, of course, but also upon her concern for her family abroad. At first she tried her luck in Hollywood, but that didn't work out for her as it did for another Ballet Russe dancer, Marc Platt. I have a number of publicity photos of her from that time; she even did an ad for ballet slippers.

"I think her post-Ballet Russe career must have been humiliating to her," Salz continues. "Her training and talent were of a far higher caliber than the things she had to do to survive. The peacock costume, for instance. She couldn't have done much dancing in it. It had a motor in the back that activated the peacock's 'display.' It was almost a burlesque contraption. I think the Weegee photo captures her nervous unease at her situation.

"At the time of the peacock costume, my mother's ballet career was clearly in trouble. I think she assumed that the choreographer of the moment, George Balanchine, would not care for her figure and style. First of all, he would probably think she was too zaftig. And then his connection with Stravinsky made his choreography more angular and formal--almost the opposite of the old-fashioned Russian School in which my mother was trained and the lighter French style of the Ballet Russe.

"She then met Sam Salz, a well known art dealer, who was 22 years her senior. They married in 1942. Sol Hurok, the ballet impresario, was the matchmaker. They lived first at a hotel on Park Avenue, where my father had his headquarters, selling Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. When they bought their own house on East 76th Street, it became the new center for my father's art dealing. Meanwhile, they had produced two sons--me, and my brother André, who is a year younger.

"My mother disliked my father's insistence that his gallery and his domestic life occupy the same space. The "customers," who included Rockefellers and Mellons, came in the evening as well as the daytime. We were all told to be very quiet while they considered the pictures my father was selling. After they left, my mother would yell "The coast is clear!" and we could come out of our rooms and relax.

"The pressure of always putting on a show for those people really got to my mother. She was a person who hated snobbism and had that direct Dutch character of always stating her opinion. Her personality was in a way like Dutch weather. The clouds in Holland sometimes block out the sun, sometimes let it shine through. Different moods for different times, and you had to be prepared for both. My parents divorced in 1970.

"I never saw my mother dance, and, as the years went by, she talked less and less of her dance career because it belonged to a world that existed in the distant past. It was nice to go to the ballet with her, though, because she would occasionally comment on the dancers' moves. 'Oh, that was off!' 'Oh, that's good!' It was like being at a basketball game. Balanchine became simply one of the men who came to our house to play bridge and gin rummy with my father, along with the pianist Vladimir Horowitz and the cellist Gregor Piatagorsky."

After being captured by two very disparate popular artists--Weegee and Hirschfeld--in the forties, Franca sat for a pair of portraits by the Dutch Fauvist painter Kees van Dongen. Salz believes that his father commissioned the pictures in Deauville in the mid-fifties. The stronger of the paintings--Portrait of Marina Salz--seizes the vivid energy intimated in the meager but telling accounts we have of Franca. Serendipitously, the public will be able to view this image May 4-8 at Sotheby's (1334 York Avenue at 72nd Street, New York City), where it will be offered in an auction of Impressionist and Modern Art on May 9.

Salz prefers not to dwell in print on the last phase of Franca's life, which was dark, plagued by deteriorating health and spirits. For publication, he reports simply, "During the seventies, my mother had a ninety-acre country estate in Bedford, Pennsylvania, which she helped create with her new partner, who was Russian. Together they named the place Swan Lake. My mother died there peacefully in 1999."

Franca's son has proffered his information in the hope that his mother will be remembered. By strange coincidence, this addendum is being posted on the 90th anniversary of her birth. Far be it from me, then, to deprive Salz or Marina Franca herself of the Heaven-bent apotheosis that ballets of the past deliver so generously.

© 2007 Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on April 5, 2007.

April 5 (Bloomberg) -- The three dancers in ``Becky, Jodi and John'' are simply playing themselves.

Becky is Becky Hilton; Jodi is Jodi Melnick. Both women have been important figures in groundbreaking dance -- Hilton, an earth-mother type, chiefly with Stephen Petronio and Lucy Guerin; Melnick, swift, sweet and smart, with Twyla Tharp and now Trisha Brown. John is John Jasperse, creator of this piece and just about as celebrated as downtown choreographers get.

Each of them is 43 years old, and while they've been good buddies for some two decades, they've had no major stints of dancing together before this. Jasperse says they've hooked up now at New York's Dance Theater Workshop to share the often devastating experience of growing old in the land of the young.

Then how come this piece is so sanguine and audience- friendly? Its subject is one few dancers can face with equanimity -- the inevitable early end of a performing career based on youthful athletic prowess. What's more, Jasperse has made his reputation with work not given to sentiment. His usual product is brainy, dead set against easy beauty, familiar with the prevailing weather in the lands of gloom and doom.

Then again, ``Becky, Jodi and John'' isn't so much about dancing after all. It's mainly about friendship that's long, deep and likely to last forever. This is evident in the serenity with which the three dancers move, often watching each other as one might contemplate a landscape, and in the way their bodies seem to know no embarrassment in the others' presence.

Foot Fetish?

In one illuminating scene, John enters bare-armed and bare- legged, carrying a stack of boxes that conceals his equally naked chest and pelvis. He lets the boxes thud to the floor. Jodi moves in, standing as close as she can without touching him, and stares, long and calmly, at his now public parts. Then they move into a duet of taking turns half collapsing, as if fainting, each repeatedly rescuing the other with a deftly timed supporting arm before she or he hits the floor.

The piece has its share of typical Jasperse tactics, especially movement in which every body part -- hand, foot, the back of a leg -- is revealed as unique, grotesque and wonderful. (How often, outside Japan, does one encounter lovemaking in which the foot plays a major role?)

Nudity, of course, is one of this choreographer's basic tools. He has spiced this dance in particular with action from props, some of it witty, some silly, all of it adding to an ambience of personal charm. Hahn Rowe's strange and lively score, commissioned for the occasion and played onstage by the composer, adds aptly to the mix.

``Becky, Jodi and John'' is too flimsy to become a highlight of Jasperse's resume. As a bagatelle, though, it provides a fair measure of enchantment.

The John Jasperse Company continues at Dance Theater Workshop, 219 W. 19th St. in New York, through Apr. 7. Information: +1-212-924-0077 or http://www.dtw.org.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary