Seeing Things: June 2005 Archives

From June 3 - 11, 2005, at Copenhagen's Royal Theatre, the Royal Danish Ballet celebrated the 200th anniversary of the birth of August Bournonville, the dancer, choreographer, and ballet master who made the company unique and gave it its international cachet. In a SEEING THINGS series called “Total Immersion,” I wrote 15 essays about the performances, which encompassed the entire extant Bournonville repertory, and about the many complementary events that were scheduled. As an introduction to the subject, I posted my essay on the first Bournonville Festival, published in Dance magazine in 1980.

Here is a list of these pieces, giving the specific subject of each and the direct link to it:

“The Festival in Copenhagen,” TT’s Dance magazine essay on the 1st Bournonville Festival in 1979

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/05/the_bournonvill.shtml

NO. 1 (Introduction; Kermesse in Bruges) http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_12.shtml

NO. 2 (Exhibition of costumes for the Bournonville ballets at the National Museum)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_11.shtml

NO. 3 (Napoli)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_10.shtml

NO. 4 (La Sylphide; La Ventana)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_9.shtml

Related material:

Link to TT’s SEEING THINGS review of the premiere in 2003 of the Nikolaj Hübbe production of La Sylphide:

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2003/09/the_danes_at_ho.shtml

NO. 5 (Three exhibitions, curated by Knud Arne Jürgensen, on Bournonville and Hans Christian Andersen)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_8.shtml

Related material:

Link to the online version of Digterens Teaterdromme (The Poet’s Theatre Dreams), curated by Knud Arne Jürgensen:

http://www.kb.dk/elib/mss/hcateater/

Link to an English translation of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Ice Maiden:

http://www.andersen.sdu.dk/vaerk/hersholt/TheIceMaiden_e.html

Link to an English translation of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen:

http://www.andersen.sdu.dk/vaerk/hersholt/TheSnowQueen_e.html

NO. 6 (Abdallah)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_7.shtml

NO. 7 (Far from Denmark)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_6.shtml

NO. 8 (The Bournonville Schools)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_5.shtml

Related material:

Link to TT’s SEEING THINGS essay, “Ballet Boyz, Danish Style”:

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2004/01/ballet_boyz_dan.shtml

NO. 9 (Konservatoriet)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_4.shtml

NO. 10 (Exhibition of photographs of the Royal Danish Ballet down the decades)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_3.shtml

NO. 11 (The King’s Volunteers on Amager)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_2.shtml

NO. 12 (A Folk Tale)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_1.shtml

Related material:

Link to TT’s Dance Insider essay on A Folk Tale:

http://www.danceinsider.com/vignettes/v0926.html

NO. 13 (“Bournonvilleana”—the gala closing performance of the Royal Danish Ballet’s 3rd Bournonville Festival)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias1/archives/2005/06/total_immersion.shtml

NO. 14 (Miscellany)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_14.shtml

NO. 15 (Operan—the Royal Theatre’s new house for opera and ballet)

http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/archives/2005/06/total_immersion_13.shtml

Royal Danish Ballet: Bournonville Festival / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / June 3-11, 2005 / Operan, the Royal Theatre’s new house for opera and ballet

With the Bournonville Festival, the Royal Danish Ballet looked back to the past and offered telling examples of how it intends to preserve its singular choreographic and stylistic legacy. Appropriately, the Festival performances took place at the Royal Theatre’s Gamle Scene (Old Stage), the ornate, perfectly proportioned opera house on the King’s Square for which Bournonville restaged some of his best works when it opened in 1874, towards the end of his career. Just last fall, however, the Royal Theatre opened a brand new, forward-looking opera house—sleekly modern in design, ultra-modern in its technical facilities—that has significant implications for the Royal Danish Ballet’s future.

The Opera (Operan), as it’s called, is not intended to replace the Old Stage—which has sheltered both Denmark’s national ballet and opera companies for over 125 years—but to complement it. The dimensions of its stage and its spectacular technical capabilities are considerably grander than those of the Old Stage, and its seating capacity of 1700 is more generous too. The Royal Theatre’s opera company will transfer itself lock, stock, and barrel to the new location, while the Royal Danish Ballet intends to perform in both houses—the old and the new. Bournonville’s ballets and others requiring an intimate setting will be given in the old house; “big” ballets, both old (Swan Lake, for example) and new (such as John Neumeier’s The Little Mermaid, recently created for the RDB) will take advantage of the spaciousness and mechanical wonders of the new quarters.

It might be observed that the Royal Danish Ballet ranks among world-class troupes for its custodianship of the Bournonville oeuvre. It has never distinguished itself internationally through productions of the nineteenth-century Russian classics. In the past it has had neither the size nor the dancers bred for the particular strength and style the job requires. Its virtues, remarkable ones, lay elsewhere—in the realms of buoyant grace, the subtle observation and communication of human feeling, and an élan that glows rather than attempting to dazzle. But, inevitably, times have changed, and the company’s aspirations are now heroic in scale and avid. The big question remains: If the RDB, responding to the opportunities and challenges the Opera offers, sets its sights on producing a Swan Lake or a Sleeping Beauty that will rank with the stagings of, say, the Paris Opera Ballet or the Kirov, will it still be able to give Bournonville his due? At the moment, it’s pleasanter to leave this troublesome question in the background and experience the Opera as a piece of beguiling architectural theater.

If, from the entrance of the Old Stage, you walk down the picturesque canal street of Nyhavn, you’ll see the imposing Opera across the water, on the island of Holmen. You get to it by boat. The ride across the water takes exactly three minutes, and the boat is merely a small ferry, but still . . .

The building itself, with its curvilinear shape and an overhanging roof that seems to float, makes you think “ship.” This is only appropriate, since the formidably costly structure was the gift of a man, one A.P. Møller, whose family made its fortune in ship building and transporting cargo over the water.

The Opera is masterly in its command of space and light and typically Danish in its harmonious juxtaposition of materials: glass (miles of it, it would seem), stone (in subdued shades of grey and sand that give it an eerie lightness), steely metal, and lovingly treated wood. The interior of the building continually echoes the curved shape of the façade. At the hub of the public space is a gigantic bowed form clad in glowing maple veneer. Fantasy suggests it’s the work of a violin maker operating on a Brobdingnagian scale. Exquisitely varied in its grain, burnished to a rich copper sheen, the wood looks as if each piece had been chosen for its singular beauty and placed so as to make a spectrum of subtle contrasts with its neighboring pieces. The convex side of this structure is the spatial and decorative heart of the building’s tiered promenades. Functionally—as if it were there merely to be useful—it forms the outer shell of the auditorium. Discovering its double life is a small but very particular delight.

At every level of the promenades—there are four of them over the ground floor—you can look out over the water, through the horizon-wide curved windows, setting your drink, libretto, or glittering minaudière on the narrow steel shelf placed at ship’s-rail height, and pretend you are on a pleasure cruise, sailing for the destiny of your dreams. You can dine on the promenades too; one malcontent observed that the Opera was conceived as a bar/restaurant with entertainment. The audience likes it, though, and dresses up marvelously to be players in the scene—the elder and wealthier in an expensively tasteful mode Scandinavian fashion has brought to a high and perfect pitch, the young with unquenchable rakish imagination.

Like the best Danish design for the home, particularly the sublime “Danish Modern” furniture of the mid-twentieth century, the Opera manages to be both austere and welcoming. Its sole concession to a lower-brow yen for glitter rests in a trio of round chandeliers—more than ten feet in diameter, I’d guess—that are suspended over the first tier. Faceted like supersized Swaroski crystals, the globes gaudily refract tones of silver, cool gold, rose, and ultramarine. A grid inside them is studded with tiny lights on stems—for all the world like a giant’s matchsticks.

From the promenades, gangways lead to the auditorium’s seating areas, adding to the visitor’s general impression of being on a luxury ship, safely ensconced in elegance, with a view of the world outside that he or she is blithely gliding past. The most splendid view of that world is to be had at the two highest tiers. That perspective best reveals the small ornate towers of Old Copenhagen, springing up from the otherwise modestly low cityscape, as if they were cunningly fashioned pop-up toys.

After reveling in the extravagant light and space of the public areas, you’re shocked by the enclosed darkness of the auditorium. The contrast constitutes a theatrical coup in itself. The interior is paneled with a Japanese-style arrangement of slatted wood in two tones of brown—deep and deeper. The wood is pierced with little lights so that, once seated, you can actually read your program, but the room as a whole, with its balconies seeming to embrace the stage as you look towards it, instills a feeling of intimacy. In this it declares its cousinship with the Royal Theatre’s Old Stage.

After reveling in the extravagant light and space of the public areas, you’re shocked by the enclosed darkness of the auditorium. The contrast constitutes a theatrical coup in itself. The interior is paneled with a Japanese-style arrangement of slatted wood in two tones of brown—deep and deeper. The wood is pierced with little lights so that, once seated, you can actually read your program, but the room as a whole, with its balconies seeming to embrace the stage as you look towards it, instills a feeling of intimacy. In this it declares its cousinship with the Royal Theatre’s Old Stage.

Turning your back to the stage and casting your glance upward, however, you see the auditorium’s second coup de théâtre. The depth of the four curved balconies creates a sense of immense sweep. This impression of vastness is augmented by the overarching vault of the ceiling (clad like the walls in striated wood). Everywhere the dark wood is pierced with tiny dots and fine lines of light, suggesting the elements that sparkle from an immense distance in a nighttime sky. The whole creates an effect of galactic grandeur.

In the intermission you can stroll the long swath of a curving outdoor promenade and, at this time of year, early June, watch the sun go down. The last fiery rays drop below the horizon just before 10:00, yet the sky remains luminous and the water graciously reflects it. This coup de théâtre by Mother Nature, co-opted by the Opera’s architect, Henning Larsen, makes you feel the universe is holding its breath.

Photos: Lars Schmidt

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Royal Danish Ballet: Bournonville Festival / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / June 3-11, 2005

When I titled my series of articles on the Royal Danish Ballet’s 3rd Bournonville Festival “Total Immersion,” I truly meant total. In the 13 pieces preceding this one, I aimed to concentrate on covering all the performances of the existing Bournonville ballets—which were, after all, the heart of the Festival—and what seemed to me the most compelling Bournonville-related exhibitions. But there was more, much more—some of it open to the public, some of it organized especially to familiarize foreign journalists and other interested parties with Bournonville’s world.

In addition to the exhibitions I’ve written about at length in the “Total Immersion” series, there were a few I didn’t have the time and strength to report on. These included Alt dandser, tro mit ord! (Everything dances—take my word for it!) at Thorvaldsens Museum, curated by the musicologist Ole Nørlyng. It explored the link between Bournonville and the neoclassical sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), whose dulcet idealization of the human form greatly influenced the choreographer. The prolific research librarian Knud Arne Jürgensen produced yet another exhibition—this one at Bournonville’s home in Fredensborg, a suburb of Copenhagen favored by the Danish royal family—placing the choreographer in the circle of his family and in the wider but similarly intimate circle of his friends in the arts. And so on. I couldn’t help feeling it was a pity that the life of the exhibitions was almost as ephemeral as dancing. Still, as I’ve written, Digterens Teaterdrømme (The Poet’s Theater Dreams) is available in a splendid online version, while Tyl & Trikot, the imaginative display of costumes for the Bournonville ballets, has been extended until July 10 and is accompanied by a useful catalogue, available through the National Museum.

In addition to Anne Marie Vessel Schlüter’s six lecture-demonstrations on the Bournonville Schools—open to the public and a huge hit with the Festival audiences—there was an illuminating and vastly entertaining invitation-only program on mime, organized by the effervescent Dinna Bjørn. It explored—with piquant demonstrations—the connection between the mime in the Bournonville ballets and the mime used in the playlets given nightly at the Peacock Theatre in the pleasure gardens of Tivoli, the site of Europe’s longest unbroken tradition of commedia dell’ arte performance. Bjørn, who now heads the Finnish National Ballet, after a distinguished career as an RDB dancer, began her theater life as a diminutive devil in one of the Peacock Theatre pantomimes, when her father, Niels Bjørn Larsen, headed both the RDB and the Tivoli troupe. Bjørn’s program was given on the raked stage of the eighteenth-century Court Theatre, where Bournonville himself once danced, and which now houses the Theatre Museum, an enchantment in itself. On another day, journalists were treated to a full performance of a pantomime play at the Peacock Theatre and a tour of the minuscule backstage quarters where all the stage machinery, including the device that unfurls and retracts the peacock-tail curtain (it’s constructed like a fan), is worked by hand.

Other mini-excursions included a trip to Fredensborg to view Bournonville’s home (see above) and to visit the Bournonville family’s burial site in the Asminderod churchyard—all simplicity, greenery, and peace. There, according to Jewish custom, I lay a small stone on the grave markers of the master and his father, Antoine Bournonville, who headed the Royal Danish Ballet when his son was young and, presciently, took the boy to Paris, where he learned—and then co-opted—the French Romantic school of dancing.

The RDB company and school, which were operating behind firmly closed doors at the first Bournonville Festival in 1979 have adopted a new policy of openness in recent years, so journalists were allowed to observe a number of classes and rehearsals. Though I didn’t attend any this time, I’ve happily done so on earlier visits, since a behind-the-scenes view can provide piercing insights into what you see on stage. Last year, in these pages, I explored the issue of the extraordinarily high caliber of the RDB’s male dancers by looking into the training of the boys and young men in the company’s school. To read Ballet Boyz, Danish Style, go here.

The Festival also celebrated the recent or upcoming publication of a slew of Bournonville items. A complete list of them appears here. I’m looking forward to reading Bournonville’s travel letters to his wife, who stayed home with their six children while her husband spent half a year in France and Italy, though, as the inscription atop the Royal Theatre’s proscenium says, “ei blot til lyst” (not for pleasure alone); the choreographer’s observations and experiences abroad, we’re assured, became part of his ballets.

Throughout the Festival, hospitality, a Danish specialty, was lavished on the visiting journalists and, of course, their local colleagues. Each participant—and there were over one hundred of us—was greeted as if he or she were a combination of dignitary and close family friend. Each was presented with a sturdy slate gray carry-on discretely marked with the Royal Theatre logo (in a gold that managed not to glitter) and weighted with publications connected to Bournonville and the Festival, from books to pamphlets to detailed lists of enticing events. Every round of activity seemed to conclude with the provision of (at the very least) sandwiches and glasses of wine, and every professional need, from general information to Internet use, was answered, with infinite cordiality, by the Royal Theatre’s press department staff. After every performance, there was a reception, at which speeches, food, and drink flowed lavishly, and excitement at being part of a telling moment in dance history ran high. Most of us went home to terrifying amounts of work that had piled up in our absence. What we really needed, instead, was a week on a deserted beach where we could lie inert, staring at the sea and sky, letting memory sort out and store up our experiences.

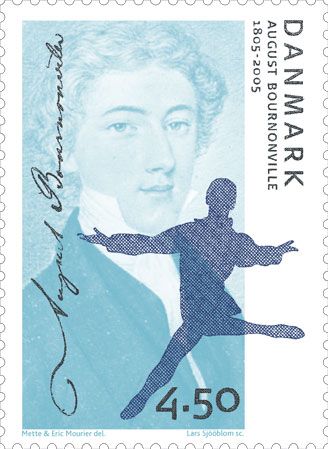

Photo: One of the two Danish postage stamps issued to commemorate the 200th anniversary of August Bournonville’s birth. The art is by Mette and Eric Mourier; the engraving, by Lars Sjööblom.

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Royal Danish Ballet: Bournonville Festival / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / June 3-11, 2005

The evening of the final, gala, performance in the Royal Danish Ballet’s Bournonville Festival opened with Queen Margrethe II’s entering the Royal Box—as she had every night of the nine-day celebration—to smile down benignly at the audience that had risen in respectful silence at her entrance. Now she was accompanied by her consort, Prince Henrik, and, as she had been several times before, by one of her sisters, Princess Benedikte. The orchestra proceeded to play the Danish national anthem, followed by the imposing “March of the Gods,” from J.P.E. Hartmann’s score for Bournonville’s Nordic-mythology ballet The Lay of Thrym. Two significant realms of authority having thus been invoked, Frank Andersen, the Royal Danish Ballet’s artistic director, gave a speech before the curtain, which then rose on the company’s future—the children of its school, performing the elementary exercises of a profession Bournonville’s ballet-master father called “the most glorious career in the world.”

The dancing that ensued consisted of lively excerpts from ballets shown in the course of the Festival, but now, in several cases, with principals we hadn’t yet seen in the leading roles; short pieces that are all that remain of longer works, such as the beguiling pas de deux from The Flower Festival in Genzano and the cheeky duet from William Tell; and a sprinkling of historical curiosities. The brief numbers were danced, appropriately, before an enlarged engraving of the old Royal Theatre, where Bournonville did most of his work. (That house was torn down in 1874, upon the opening of the present theater, which has served the Danish ballet so well, though the new Operan, as I’ll explain in the final installment of “Total Immersion”—No. 15—now threatens to eclipse it.)

In another backward glance, fragments of film shot by Peter Elfelt in the first years of the twentieth century provided a glimpse of Bournonville dancing as it looked 100 years ago. Perhaps unintentionally (perhaps cannily), it reinforced the point that the Andersen makes over and over again when present-day Bournonville aficionados succumb to overdoses of nostalgia: The Bournonville style can’t be frozen in time but must move forward to suit today’s bodies, today’s technical capabilities, and today’s taste. (As for me, I’m guilty of the nostalgia and worried, in this death-of-poetry era, about the issue of taste.)

The program concluded with a rip-roaring performance of the third act of Napoli, with dancers of all ages crowding the stage at the ebullient climax, the most agile dividing the solo work among themselves; those of riper age taking their turn at a few phrases or banging an encouraging tambourine on the sidelines; and what appeared to be the entire student body up on the bridge from which, traditionally, the young pupils look down on the soloists performing the pas de six and tarantella and memorize their parts.

At its close, the program, broadcast live over Danish television, was greeted with a prolonged, tumultuous ovation. Balloons were duly let loose, and confetti, in the form of tiny Danish flags, rained down from above. Andersen gave the first curtain calls to the dancers. When he finally appeared for his bow, in front of the applauding ranks of performers, facing an audience that had risen to its feet (not an everyday occurrence in Copenhagen), if I’m not mistaken—I saw his face from a distance, in a dazzle of stage light—he was in tears.

I think Andersen had earned the adulation he received. Whatever quibbles one might have over some of the artistic choices (and I have several fairly serious ones), this Festival was a triumph simply as an event, and Andersen, though he has continually given ample credit to the stagers, dancers, coaches, teachers, and staff “without whom,” was the leading force in bringing it about. Who else would have thought of finishing the festivities with a glorious display of fireworks on the King’s Square, right in front of the Royal Theatre, spelling Bournonville’s name out in lights, as it were, and firing up the sky with a brilliant fantasy of explosions in which stars turn to flowers, and comets acquire rainbow tints?

Photo: Official poster for the Royal Danish Ballet’s 3rd Bournonville Festival, June 3-11, 2005, created by Peter Bonde

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Royal Danish Ballet: Bournonville Festival / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / June 3-11, 2005

I first saw Bournonville’s A Folk Tale in 1979, at a dress rehearsal to which journalists who’d made the pilgrimage to Copenhagen for the first Bournonville Festival had been invited. (A Royal Danish Ballet dress rehearsal means a full-fledged, uninterrupted performance with almost no one in the audience apart from the company’s current personnel and its venerable retired dancers.) At that time, Bournonville had not yet been fully “discovered” by the international dance world; most of us visitors were ignorant even of the ballet’s plot—to say nothing of the virtues that place it easily among the great achievements of Romantic art. Between the ballet’s two acts, as the small number of privileged spectators from abroad stumbled from the darkness of the auditorium into the sunlit foyer, I encountered the dance critic and historian David Vaughan, a longtime colleague and friend. I remember that neither of us could speak; we were both weeping. The work was so tender, so luminous in its fantasy—and so very Danish—that it seemed beyond the reach of words. This is how I described it eventually in the essay I wrote on the 1979 Festival for Dance magazine:

“Bournonville’s A Folk Tale . . . is as shimmering, delicate, and self-contained as a soap bubble—the product of a unique imagination.

“The argument of the ballet is a fairy-tale staple: an exchange of infants from dichotomous backgrounds who grow up to uncover their true nature. Here a human child of the gentry is secretly replaced in her cradle with a baby of the troll colony that lurks, half-hidden, in its under-the-mountain (that is, subconscious) domain. The switched girls grow to maidenhood, each instinctively revealing or seeking her roots. Although the human Hilda is promised by the dowager troll to the more loutish of her two sons, she yearns for an ideal goodness, which the ballet symbolizes, endearingly, by Christianity and the handsome young hero, Junker Ove. On the other hand, despite the gentility of her upbringing, Birthe remains a troll at heart and, aptly, in body. In one of the ballet’s most entertaining and psychologically keen sequences, she dances before a full-length mirror, in narcissistic, lyrical phrases—into which contorted troll-motions break uncontrollably.

“The ballet contains a vestige of the themes of Romantic preoccupation—in the elf-maidens (a cross between the wilis and the nightgowned muses-with-flowing-hair in the Élégie section of Balanchine’s Tschaikovsky Suite No. 3) who emerge from their mountain caverns and swirl through the dry-ice fog to entrap Junker Ove, and in Ove himself, a sketchy indication of the morbidly dreamy temperament of the model Romantic hero. But the ostensible villains of the piece, the troll folk, feel harmless—because they are so quaint. (The second brother eventually grows as lovable as one of Snow White’s dwarfs.) This is a common folkloric device—subverting the potency of figures of mystery and fear by rendering them whimsically. But the real mark of Bournonville’s genius is that, at the same time, he is able to make the entire troll community a riotously accurate personification of the human race in its less attractive guises. I’m particularly fond of the show of self-congratulatory indulgence in the minor vices revealed at their orgy, but Bournonville’s deftest shaft may be in making the most characteristic attribute of these appalling creatures their bad manners.

“Of course Bournonville, that inimitable proselytizer for joy, gives his story a happy outcome. What is remarkable about this closing scene in A Folk Tale is that one is wholly disarmed by the sweetness and purity of his means. The ballet ends, naturally, with the wedding of the lovers made for each other, Hilda and Ove. Imagine this sequence of images: six very young women (blond nymphets in pale green dresses, holding blossoming branches) softly waltzing; a slow processional, bland as a walk, for the wedding party, under wreaths of flowers; then, oddly slowed, the simplest of love pledges—the hand to the heart, then extended to the partner; a brief dance around a pastel-ribboned maypole; and the final assertion of the dulcet waltz motif accompanying a flurry of rose petals. Few artists could work with such trusting innocence.”

I have written about A Folk Tale many times since I made the above wonder-struck report, most recently in an essay for Dance Insider, on the ballet’s theme of “home.” My love of this ballet survived the new production in 1991, by Anne Marie Vessel Schlüter and Frank Andersen, with costumes and décor by Her Majesty Queen Margrethe II, that I thought coarsened it—and, where the trolls were concerned, thoroughly Disneyfied it. This production is still in use today; overall, it has not acquired nuance or luster with time.

The 2005 Festival cast was distinguished, nevertheless, by the performances of Gudrun Bojesen as Hilda, Kenneth Greve as Junker Ove, and Tina Højlund as Birthe. All glowing innocence, Bojesen embodied, as Hilda should, the unsullied loveliness of the young. Today, Bojesen is more conscious of her effect than she was earlier in her career, but if—as is only natural and inevitable—some of her former dewiness and reticence has vanished, it has been replaced by the growing knowledge of her particular dancing persona and the confidence in her powers that are marks of a ballerina coming into her own. Greve fulfilled, excellently, the “type” he was playing—a beautiful, brooding young man instinctively aspiring to perfect love. Højlund, as always, performed with enormous energy and spontaneity, creating a lightheaded, lusty Birthe who relishes her own deviltry, yet spares an occasional wistful sigh for the joys of a virtuous, civilized world that she will never have.

As I’ve commented, discussing other Festival productions, the music here was played too fast for the mime to register properly—and mime, an expressive mode that refuses to be rushed, is every bit as essential to A Folk Tale as dancing. On the other hand, mime portrayals that I thought slim a while back have deepened, notably Eva Kloborg’s Muri, which has accumulated a gratifying weight and some psychological complexity, and Lis Jeppesen’s Viderik (the “good” troll brother), which is not so flighty as it was early on. Thomas Lund was outstanding in the "Gypsy" pas de sept (classical fireworks inserted to liven up the dulcet wedding scene that concludes the ballet). He’s still the only guy in the company able to make the Bournonville style look entirely natural.

The wedding scene itself should, with its calm, ever-modest radiance, sum up everything that has gone before, yet now it doesn’t, quite. It’s as if the collaborators on the production—the stagers, the coaches, and a majority of the dancers—either didn’t understand its intrinsic qualities (which are, at heart, spiritual) or simply didn’t value them. In its present state, there’s still enough magic in A Folk Tale to enchant Bournonville newbies, even to retain the affection of veteran Folk Tale fans, but this time round, it didn’t make me cry.

Photo: Lithograph from the cover of the piano score for August Bournonville’s A Folk Tale

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Royal Danish Ballet: Bournonville Festival / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / June 3-11, 2005

Just about everyone agrees that, among Jane Austen’s novels, Pride and Prejudice is the “perfect” one, the technical dazzler, and that Emma is the most profound. But Janeites usually have a personal—idiosyncratic—favorite, and mine is Persuasion. I’d be the first to admit that it’s slighter than the Big Two, but I find it uniquely touching in its account of quiet events and barely spoken feelings. I’m highly susceptible as well to its notion that one can have a second chance at happiness. Among Bournonville’s ballets, The King’s Volunteers on Amager holds a similar special place in my affections. At least it did.

A ballet exists fully only in the here and now. The rest is merely history and capricious memory. I’m sorry to report that the current production of King’s Volunteers, the only one my little dance-avid granddaughter can see, is nowhere up to the version—staged by Hans Brenaa, with décor and costumes by Bjørn Wiinblad—that captured my heart at the first Bournonville Festival in 1979.

The one-act ballet, created in 1871, at the sunset of Bournonville’s career, is based on the choreographer’s nostalgic recall of the Fastelavn (Shrovetide) celebrations on the island of Amager that he witnessed as child. Something of a suburb of Copenhagen, Amager was home to a farming community that had originally emigrated from Holland and had, for several centuries, retained its Dutch dress and Dutch customs. (Today, Dutch names can still frequently be found among the area’s residents, and the marvelous Amager Museum holds examples of the unique clothes and furnishings of the settlement.)

In the ballet, a party of Copenhagen townies visits a farmhouse on Amager, where, as it happens, a squad of select upper-crust soldiers has been stationed to guard the vulnerable coast against enemy bombardment. Unfolding amidst the quotidian events of the scene is the bittersweet romance of a couple in midlife—Edouard, a womanizing husband, and his sorrowful but still loving wife, Louise. (Bournonville based the character of Edouard on a real historical figure, Jean Baptiste Edouard Du Puy—versatile musician, dashing soldier, and constantly inconstant lover. He was known, with admiration and dismay, as the "Don Juan of the North.") Saddened by the incessant amorous exploits of her philandering spouse, Louise—a role for a ballerina with some history behind her—tricks him, in a masked dance, into attempting to seduce her. When they unmask, he comes to his senses and then, slowly and gravely, declares his lasting love for her. “You are the only one,” he mimes, and, for the moment, both of them pretend to believe it. This interchange is ingeniously embedded in an exuberant community dance that happily mixes young and old, elegant city dwellers and salt-of-the-earth farmers, folk dancing, classical dancing, and hectic carnival pageantry. The reconciliation, which, Bournonville suggests, may or may not prove enduring, is effected at a moment when Edouard and Louise are the only two, on a stage crammed with boisterous revelers, who are standing still.

In general, the new staging, by Anne Marie Vessel Schlüter, is neither subtle nor sensitive enough. It’s marred, moreover, by an addition meant to explain matters when they need no explanation—a dream sequence in which, to spell out Edouard’s proclivities, he’s made to dance with a quartet of anonymous beauties in pink nighties. The choreography devised for this segment is so banal as to be beyond comment.

The new décor and costumes by Karin Betz are even more unfortunate. The city girls are dressed in a medley of persimmon, hotted-up pinks, and reds blatantly hostile to the eyes, while the Amager folk, whose actual native costume for women featured lavish embroidery in glowing tones, are garbed so as to emphasize the flat, uncompromising black, red, white, and blue of the clothes’ background. You’d think, from the look of things, that the community embraced stringent denial rather than reflecting life’s richness.

The décor manages to be harsh and quaint at once, in the latter aspect much like a stylized picture postcard conveying a tourist’s greetings from Amager. Betz goes wrong again by placing, upstage center, a huge painting of a rural landscape in summery flowering, while the community’s children are seen sledding and throwing snowballs. The use of a picture—the kind you might hang on a wall, if you had the space and it weren’t so inept—is in itself disturbing. Like the designer of the new, misconceived set for La Ventana, Betz has opted for indicating semi-abstractly what used to be represented realistically. Please God, this does not indicate a trend.

If a ballet fully exists only in a current staging, its life depends equally on the current interpreters of its key roles and—in the case of character parts—of its minor roles as well. The King’s Volunteers cast for the Bournonville Festival came nowhere near the richness of the cast for the first Festival in 1979, which still burns bright in my memory. It featured the consumate dancer-actors Tommy Frishøi, Kirsten Simone, and Lillian Jensen—all from a genre of players that has traditionally given the RDB its distinctive luster and that nowadays seems ignored in favor of other concerns.

True, in the present production, Silja Schandorff has made a credible start on the role of Louise, even if her mime is a shade too close to classical dancing, and Peter Bo Bendixen is adequate as Edouard, though, handsome and stalwart as he is, he doesn’t radiate the sexual confidence of a born womanizer. Simone, who offered a heart-rending Louise in 1979, now does a vivacious job as the grandmotherly rural hostess—all housewifely bustle and robust appetite for life. Two other company veterans, Poul-Erik Hesselkilde and Flemming Ryberg, are equally convincing in smaller roles. But despite these individual efforts, the production doesn’t cohere as a story that, however slight, can gather the power to move its witnesses to tears. As a result, the inserted classical pas de trois—for dancers not involved in the story—takes on inordinate importance for the present-day audience, which responds more readily to bravura steps than it does to the deeper drama of emotional life.

Photo: Martin Mydskov Rønne: Poul-Erik Hesselkilde, Mogens Boesen, Mette Bødtcher, Ulla Frederiksen, Kenn Hauge, and Kirsten Simone in August Bournonville’s The King’s Volunteers on Amager

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Sylfider, Trolde og Linselus: En Fotografisk Rejse i Bournonvilles Balletter (Sylphides and Trolls Caught in the Lens: A Photographic Journey Through Bournonville’s Ballets) / Round Tower, Copenhagen / May 13 – June 12, 2005

Housed in Copenhagen’s Round Tower, Sylfider, Trolde og Linselus: En Fotografisk Rejse i Bournonvilles Balletter (Sylphides and Trolls Caught in the Lens: A Photographic Journey Through Bournonville’s Ballets) is a modest, pleasurable exhibition produced by the Royal Theatre and designed by Mia Okkels with the assistance of Kirsten Simone. Organized by ballet, it traces each of the main extant Bournonville works through the casts that have enriched it over time. The display feels like a family album, the family happening to be one of Denmark’s most significant in the realm of culture.

One way to look at this exhibition is to choose a single dancer and trace his or her career through the repertoire. A number of the artists represented are first seen as mere children, since Bournonville created countless roles in his ballets for the RDB school’s young students, to provide them with stage experience from their earliest years. The late Kirsten Ralov, for example, appears here first in Konservatoriet, as little Fanny, the child of impoverished itinerant performers, who aspires to a place in the classical-dance academy. Ralov went on to be a sparkling principal dancer and, subsequently, a teacher, a stager of Bournonville’s ballets, a company administrator, and the first to preserve the Bournonville Schools fully and formally. Nilas Martins, who was to switch his allegiance to the New York City Ballet, can be seen as one of the children taking dance class with their elders (fulfilling Fanny’s dream, as it were) in a later production of the same ballet; he’s the blond boy with the cherubic face and the gorgeous instep.

Subsequent artistic directors of the RDB are shown in their dancing days: Frank Andersen, the current incumbent, who has masterminded the third Bournonville Festival, and Henning Kronstam, under whose aegis the first—and stilll most glorious—Bournonville Festival took place in 1979. Both are “dancers who stayed,” as the company puts it. The “defectors” to Balanchine—those who were tempted away from the Danish ballet early in their careers—appear here too, on the stage that gave them their training: Ib Andersen, Peter Martins, Nikolaj Hübbe.

A number of actual families crop up: Kirsten Ralov, married first to Børge Ralov and then to Fredbjørn Bjørnsson, all three indispensable to the Danish ballet in their time; the siblings Kirsten Simone and Flemming Ryberg, classical-dance stars in their heyday who have evolved into vivid, resourceful character dancers; father and daughter Niels Bjørn Larsen and Dinna Bjørn; as well as a three-generation group consisting of Peter Martins; his uncle, Leif Ørnberg; and his son (with Lise la Cour), Nilas. Such clusters may seem to be of merely anecdotal interest, but I think they suggest something about the RDB’s tight-knit nature and long-lived traditions.

The pictures also capture history at the moment it’s being made. A 1945 photo of Far from Denmark, showing Margot Lander and Børge Ralov in the leading roles, includes Kirsten Ralov and Margrethe Schanne as the two cadets, roles traditionally given (and, in this case, aptly) to a pair of young women whose promise is on the brink of fulfillment.

As one might expect, the older photographs are the most resonant. A shot of Gerda Karstens as the witch, Madge, in La Sylphide, towards the end of her career in 1952, and two of Niels Bjørn Larsen in the same role, one from 1957, another from the 1994-95 season, show you the glories of the past. They also tell you what to look for in the role today: a keenly observed persona that is physically and emotionally developed in detail and coupled with ferocity of projection.

Two of the most striking images in the display record a pair of haunting embraces from La Sylphide. One, from the 1966-67 season, shows the consummate danseur noble Henning Kronstam cradling the head of the dying Sylphide (Anna Lærkesen) as she falls back in his arms. His face is a mask of sheer poetry, summing up love, longing, and loss in a single sublime moment. In the other, from the 1979-80 season, Sorella Englund, as Madge, embraces Arne Villumsen’s half-fainting James from behind, inserting her face, all grinning malevolence, next to his as if she were some terrible twin to the beautiful man whose ruin she has helped Fate execute. Viewers may notice that both Kronstam’s and Englund’s hands echo what their faces express. This congruity—half instinctive, half consciously honed—is something to look for in a performing artist likely to go down in the history books.

Two of the most striking images in the display record a pair of haunting embraces from La Sylphide. One, from the 1966-67 season, shows the consummate danseur noble Henning Kronstam cradling the head of the dying Sylphide (Anna Lærkesen) as she falls back in his arms. His face is a mask of sheer poetry, summing up love, longing, and loss in a single sublime moment. In the other, from the 1979-80 season, Sorella Englund, as Madge, embraces Arne Villumsen’s half-fainting James from behind, inserting her face, all grinning malevolence, next to his as if she were some terrible twin to the beautiful man whose ruin she has helped Fate execute. Viewers may notice that both Kronstam’s and Englund’s hands echo what their faces express. This congruity—half instinctive, half consciously honed—is something to look for in a performing artist likely to go down in the history books.

Girding the real photographic history of Bournonville’s ballets at the center of this show is a series of photographs commissioned by the Royal Danish Ballet for its 2005 calendar. It offers some dismaying evidence of how the company sees its future, how it intends to cope with making Bournonville appeal to a young generation of spectators who couldn’t care less about the treasures of the past. The photographer, Per Morton Abrahamsen, fancies himself a “visual provocateur.” By his own admission, he knew next to nothing about Denmark’s great nineteenth-century choreographer and his ballets before undertaking the assignment. After the fact, apparently, he understands even less. Nevertheless he produced a dozen mise-en-scenes in which—claiming to modernize the tales told by the ballets, to free the action from, as he puts it, the repressions of “Victorian piety”—he trashes them with a vulgarity so cheap and superficial, it would make you laugh if only you weren’t crying. (Let’s assume the translator meant “propriety.”) For the sake of fairness, let me add that, in a few cases, as in his response to sylphdom, Abrahamsen merely sentimentalizes his subject, in the manner of an ad for perfume.

For the most part, the work reflects the cool young crowd at play, with lots of slick, noir eroticism, complete with criminal violence and conspicuously populated with victimized women. One svelte-bodied beauty seems to have been raped. Another is being flung out of a high window (grinning, mind you) into the dubious embrace of a firefighter’s net manned by a bunch of guys stripped to display their pecs—if, indeed, by good or ill luck, she misses hitting the pavement below. I forget which of Bournonville’s ballets these images purport to represent. For Abdallah (think “harem”), Abrahamsen gives us the club scene, artfully streaked with fire and crowded with glossy bronzed bodies. The available ladies are nude (breasts much in evidence, pubic area coyly turned away or airbrushed), while the sole gentleman (I use the word advisedly) keeps his shiny black boxers on—for fear, I guess, of offending some oldster who may still be hewing to Victorian hang-ups.

This exhibition also includes a collage of film and video taken from the archives of the Royal Theatre and arranged by Ida Wang Carlsen. It was too dim to see the day I visited the Round Tower, so I must take its virtues on faith. Its background music, co-opted from the scores of the Bournonville ballets, was inescapable. I do wish—in vain, I know—that the fashion for augmenting visual exhibitions with sound scores of any kind would go away. I am a slow looker (one of the few left on earth, no doubt), and it drives me to distraction to hear the same tape loop played over and over again while I’m trying to see something. I consoled myself for this aural abuse by walking the full route of the spiraling cobblestone ramp that winds through the Round Tower. The roughness of the walkway and its just slightly precipitous pitch alert you to matters of texture and balance. And, for the eye’s delight, as you ascend or descend, you get glimpses of the gentle cityscape through the small deep-set windows that punctuate the tower’s rough white plaster walls. The Round Tower is a simple and perfect exercise in architectural purity. To experience one’s body moving through this space is, especially for a dance fan, one of the myriad small but intense delights that Copenhagen has to offer.

Photo: Mydskov: Anna Lærkesen and Henning Kronstam in August Bournonville's La Sylphide

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Royal Danish Ballet: Bournonville Festival / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / June 3-11, 2005

Bournonville’s Konservatoriet is known and loved both in Copenhagen and internationally for its Degas-like evocation of classes in the dance academy of the Paris Opera. The young Bournonville had studied there in the 1820s, and this is his tribute—created in 1849, just after he had retired from performing—to the scene and, by extension, to the French Romantic ballet. Here, in a studio redolent with echoes of the past, ravishing—and challenging—enchaînements (some of which we meet again in the Friday Class of the Bournonville Schools) are delivered in the charming context of a lesson that involves a ballet master, a pair of sisterly (or is it, ever so sweetly, rival?) ballerinas, a decorative small ensemble, and an appealing cluster of children being apprenticed to the stage.

This atmosphere-infused section, however, was only part of Bournonville’s original Konservatoriet. It was set, in two parts, into a colorful, gaily rendered story in sit-com mode indicated by the ballet’s subtitle, A Marriage Proposal by Advertisement. The full ballet was restored to the RDB repertory in 1995, from memory, by Kirsten Ralov and Niels Bjørn Larsen, who had danced in it as children in the 1930s. The ebullient tale, destined to end happily, involves the Inspector of a dance academy who—without youth, good looks, intelligence, or personal charm to recommend him—seeks a wealthy wife through the personal columns and the gifted little dancing daughter of impoverished itinerant performers, who yearns to gain admittance to the heavenly world of classical dancing. As a child, Ralov played the little girl, Fanny; Larsen had only a minor part, but hoped, in the fullness of time, to play the Inspector and so studied the role closely.

In its Festival performance, the dance academy sequence was well rendered by children, ensemble, and soloists alike. It was here that I saw most clearly how the company has chosen to dance its Bournonville today. It’s a contemporary take on the old style that offers some gains and some truly regrettable losses. In terms of technique, the dancing is conspicuously stronger and clearer than it was at the first Bournonville Festival in 1979; this is evident even in the children’s work, with no loss of the spirited quality that distinguishes the pupils of the RDB school. The work of the adult dancers is bigger and bolder than it used to be, but increased precision and force have come at the sacrifice of some of the delicacy, buoyancy, and fluidity that once made Danish dancing so singular and delightful. And of course, what with the RDB’s repertory expanding to include more and more assignments entirely alien to the Bournonville style, it was inevitable that the dancers would no longer be able to dance their Bournonville as if nothing were more natural. Still, looking at the work of Yao Wei (one of the lead women in Konservatoriet) and that of Gudrun Bojesen and Thomas Lund (just about everywhere else), you could hope that some happy reconciliation might yet be effected between the old ways and the new.

The anecdotal sections of Konservatoriet were, needless to say, dependent on the performers’ mime skills. The stand-out here was Paul-Erik Hesselkilde in the role of the Inspector. As is typical of the RDB’s veteran mimes, Hesselkilde takes a large measure of responsibility for building his character, working from the basics the choreographer has outlined. His Inspector is an aging, self-important, rather stupid fellow, decidedly short on human sympathy. He’s rudely ungrateful to the faithful old housekeeper he’d once promised to marry and curtly dismisses poor little Fanny because she can’t pay for lessons. Yet, as often happens with potential bad guys in Danish ballet, he turns out to be only foolish and, actually, rather sweet. Hesselkilde is got up to look physically unprepossessing, rather Tweedledum/Tweedledee-ish, and he has devised a complementary fumbling manner for the Inspector that belies the character’s superficial bluster. The whole thing is done with a very quiet sense of humor. This performance has absolutely nothing show-offy about it. It simply grows on you until you come to sympathize with the character, who seems to have slipped out of a novel by Trollope.

At the curtain calls for Konservatoriet, the company paid onstage tribute to Hesselkilde, who was celebrating his 40 years at the Theatre—though, mind you, he’s in no way ready to retire. The presentation of an outsize laurel wreath was duly accompanied by kind words, kisses and bear-hug embraces, floral and alcoholic offerings. Immediately afterward, Hesselkilde was feted backstage in typical RDB fashion, with serious, touching speeches from top management and a sardonically funny one from a colleague; still more gifts; a screened excerpt from a past triumph (as a wry, idiosyncratic Drosselmeier in The Nutcracker); and a hilarious live takeoff on another of his signature roles—the Eskimo dance from Far from Denmark. But backstage is another story.

Photo: Martin Mydtskov Rønne: Gitte Lindstrøm, Thomas Lund, and Gudrun Bojesen in August Bournonville's Konservatoriet

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Royal Danish Ballet: Bournonville Festival / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / June 3-11, 2005

Some of the most wondrous dancing in the Bournonville Festival came not from the ballet-by-ballet excursion through the master’s extant works on the Royal Theatre’s capacious, ornate Old Stage, but from a half dozen 45-minute sessions on the stark, small Stærekassen stage—one each for the six Bournonville Schools. These set classes formed the backbone of the Danish dancers’ training from the end of the nineteenth century through the first three decades of the twentieth and are still revered (and used) as a lexicon of the Bournonville style.

The classes, named for the days of the week and originally danced on the corresponding day (if we’re doing Wednesday Class, it must be Wednesday), were the work of Hans Beck, who led the Royal Danish Ballet from 1894 to 1915. Fearing that the Bournonville legacy might be lost, he canvassed the older dancers’ personal memories of Bournonville’s teaching. The Danes being, until our forget-everything times, compulsive recorders, many of the elders had made written notes of enchaînements they had particularly admired or—despite their fiendish intricacy—enjoyed doing. These eventually came to be accompanied by tunes that, though mostly lowbrow in quality, had an undeniable dansant quality. Augmenting this material with brief passages from the ballets, Beck made his compilations, which were then passed down, dancer to dancer, in the manner of oral literary tradition. In 1979, the late Kirsten Ralov, after much consultation with the dancers of her own generation and the preceding one, gave the classes their first published form—the choreography set down in words as well as formal dance notation, plus the accompanying scores. (This meticulous, exhaustive recording lacks only the naughty lyrics some of the male dancers devised to accompany the tunes, to relieve the boredom of executing the same exercises over and over again, from pupilhood to retirement.)

The 2005 Bournonville Festival has been the occasion for an amplification of Ralov's project, with the enchaînements reedited after further research and, most significant, a DVD on which one can see the dancers of today executing the material. The importance of the visual component is enormous. Dance scholars and teachers will no doubt benefit from reading the texts of the choreography, but dancers themselves live by watching and doing. The gift of the material in embodied form is so generous as to constitute folly. As one of the Danes associated with the project commented wryly, “Would Carlsberg give out, almost for free, its recipe for beer?”

The Stærekassen lecture-demonstrations of the Schools were led by Anne Marie Vessel Schlüter, once a spirited demi-caractère dancer with the RDB and now the energetic head of its school, who celebrated her 40 years with the company during the Festival. Her pithy introductions to the material were seconded by guest speakers who’ve had a lifetime’s association with the Bournonville legacy, among them Flemming Ryberg, one of the company’s senior Bournonville stylists; Erik Aschengreen, fondly called the dean of Danish dance critics; and the musicologist Ole Nørlyng. Then, as is only right, the talking gave way to dancing. On a given day, a lavish selection of the enchaînements belonging to that day’s class were performed by a handful of company dancers and children from the school—all as disarming in their modest demeanor as they are formidable in their prowess.

This was Bournonville laid bare. Without the support of story or scenography, here was the pure dance material, the ingenious combination of steps that excited the admiration of no less a dance master than Balanchine. These are some of the things I noticed:

First off, a pervasive buoyancy and musicality. And then . . .

Pirouettes of every sort, often taken with the working foot held demurely low, at the ankle, rather than the knee, as is now the custom. Turns on half-toe for the women, who are now used to executing them on pointe. These throwbacks to the past confront today's dancers with humbling challenges.

Small jumps adorned with flickering beats; huge sailing leaps with the back leg curved as if to outline a crescent moon.

Whirling turns and straight-up jumps springing without hesitation from juicy deep knee-bends.

Unusual shifts in balance; unexpected changes of direction; sly timing that keeps both dancer and viewer alert.

Formidably long enchaînements that zigzag through the space, incorporating everything but the kitchen sink—allegro and adagio; steps that make much of returning to a single spot on the dancing ground; others that skim over it in a diagonal path or shoot away from earth into the air; filigreed stuff suddenly splurging out into grand gestures; big moves returning to a home base that is all quiet composure.

Shifts off the vertical on the ground and, uncannily, in the air.

Unanticipated brief halts in the action so that the finish of a step is held in a frozen picture, revealing any flaw that ongoing action might kindly have concealed.

And, while the legs and feet are so busy, a complementary use of the arms (often held low, still and relaxed), the shoulder girdle, and the head—even the eyes’ glance. These tactics, called épaulement, give the dancing its beautiful plasticity and its look of sculpture that has miraculously taken on flesh and breath.

The intention throughout is to execute the killer combinations (altogether there are some 150 of them) with playful grace, so that the spectator’s impression will not be that of an amazingly built physical machine attempting the impossible but, simply, one of danseglæde, the joy of movement. Buy the DVD and its accompanying book and try it.

Photo: Henrik Stenberg: Caroline Cavallo, Mads Blangstrup, and Gudrun Bojesen in Friday Class from the Bournonville Schools.

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Royal Danish Ballet: Bournonville Festival / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / June 3-11, 2005

Bournonville’s Far from Denmark is a seemingly frivolous, trifling ballet about life at sea, but it’s anchored by poignant feeling. The Danish navy, from grizzled veterans to barely adolescent apprentices, finds itself harbored in Argentina—one of the exotic Elsewheres of Bournonville’s imagination—where passions are given a brief holiday from the decorum of Danish conduct. Though he has a fiancée (whom we never see) waiting for him back home, Wilhelm, a young lieutenant, succumbs to the seductions of Rosita, a South American belle. By turns languorous and fiery, she's something of a man collector as well, though she has her own local steady beau, predictably hot-tempered in his jealousy. Mind you, this is Bournonville, so Wilhelm’s infatuation with Rosita never goes beyond flirtation. The Danish sailors invite the Argentineans to an evening ball on board their ship, where the two cultures mutually offer gracious respect and homegrown entertainment. In the course of the hectic festivities, Wilhelm realizes where his heart truly lies. When the visitors depart, the Danish sailors let loose in a succession of shenanigans frat partyers might indulge in if they were given to dancing and happened to have a chest of outlandish costumes handy.

The story, with its themes of loyalty—fidelity in love, patriotic fervor—unfolds, largely in mime balanced by social and character dance, in the most leisurely, relaxed manner imaginable. It juxtaposes the gentlest of sentiments—love of the familiar and of the exotic, longing for what one has lost or will never have—with rough, raucous humor. To say that it is typically Danish would be redundant.

A word to the p.c. police: You’re warned to stay away from this ballet, because once you see it, you’ll feel obliged to shut it down. The Argentinean upper class it represents, entirely Caucasian, is served by mulatto servants rendered as garish caricatures. The tolerant will view this as an aspect of vintage theatrical convention. Others will be understandably appalled, embarrassed, insulted, even outraged. The fact that, in its second half, the ballet makes gross fun of a handful of other non-dominant communities—Eskimo, Native American, Chinese—and, perhaps, in the various uses of cross-dressing, of non-standard sexual preferences as well, doesn’t help any. While the viewer is in exasperated mode, he or she might care to note, moreover, that the only black faces in the Royal Danish Ballet’s productions owe their existence to the deeper hues of pancake makeup.

My own main complaint about the present production is that it looks as if the company has lost confidence in the ballet. The dancers don’t seem to inhabit their characters, to know—or to be interested in—who they are. (Mads Blangstrup is certainly the right Romantic type for Wilhelm, but he doesn’t seem to have invested enough imagination or energy in the role.) What’s more, there hasn’t been much perspicacity in the casting. (Marie-Pierre Greve makes a pretty Rosita but not an alluring one.) The practice of using senior members of the company to add an important social dimension and a gracious dignity to the shipboard party has been abandoned. (The presence of the elders may now be thought a minor concern, yet I’ll never forget Lillian Jensen, playing one of these roles in her sixties, dancing gravely and just “being there.”)

The once-tender elements of the ballet are no longer properly realized. The piquantly matched pair of cadets (young women playing young men) exaggerate their pertness, rather than delivering the sweet melancholy that’s required in the scene in which one of them gets a letter from home and the other doesn’t. Another key moment barely registers—the one in which, despite the formal hands-across-the-sea courtesies between the Danes and the Argentineans, a young naval recruit, barely into his teens, impetuously comes forward to kneel before the Danish flag and reverently kiss its hem. The “ethnic” dances, for the most part, lack the raw energy, the gleeful abandon in the absurd portrayals, and, most significant, the irony at which the Danes are so expert.

The diminished Far from Denmark demonstrates, once again, the fact that the company is no longer as eloquent in mime as it once was. The current production of this ballet suggests, further, that it no longer finds yesteryear’s forms of theater as compelling as it once did. This development was inevitable, I suppose, but it bodes no good for the Bournonville repertory.

Photo: Martin Mydtskov Rønne: Marie-Pierre Greve in August Bournonville’s Far from Denmark

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Royal Danish Ballet: Bournonville Festival / Royal Theatre, Copenhagen / June 3-11, 2005

While the Bournonville Festival is dedicated to presenting the complete extant repertory choreographed by the master, with Abdallah the Royal Danish Ballet has also made room for some faux-Bournonville.

This ballet does not claim to be part of what the Danes call “the living tradition”—works that have been passed down in an unbroken line from generation to generation of RDB artists. Choreographed in 1855, Abdallah was decidedly not a hit with either the critics or the public, and by 1858 it was off the boards. Apparently, viewers thought it contained too much pure dancing—ironically the very element to which today’s step-hungry public is perfectly willing to sacrifice the balancing element of mime.

What we’re looking at in 2005 is an ingenious and effervescent, if not entirely satisfying, latter-day concoction brought into being by Bruce Marks, an American dancer who did a stint with the Royal Danish Ballet; his wife, the Danish ballerina Toni Lander Marks; and Flemming Ryberg, a principal dancer and mime with the RDB and an incisive Bournonville stylist. This resourceful little committee based its production on Bournonville’s telling but incomplete choreographic notations in the musical score, preserved in the Royal Library. The three shaped and augmented that information with their own rich knowledge of the extant Bournonville repertory and keen theatrical savvy about what might attract a contemporary audience. The “modern” Abdallah was given its premiere in 1985 in Salt Lake City, Utah, by Ballet West, where Bruce Marks was artistic director. It entered the RDB repertory the following year.

As its title suggests, Abdallah is an Arabian Nights tale—ravishingly decorated in that vein by the late scenographer Jens-Jacob Worsaae. It’s set in Iraq, and its opening act—which features a barrage of Bournonville-style dances—is further churned up by a bit of regime change. The poor shoemaker, Abdallah (a fellow of “very few brains” but infinite ingenuous appeal) courts the local reigning beauty, Irma. He succeeds in winning her heart, though not that of her virago of a mother who’d hoped for a more prosperous match. Suddenly the town is turned upside down by an armed band trying to get rid of the local sheik. Abdallah saves the ruler’s life and is duly rewarded with a five-branched candelabra that will grant him the desires so common to raw male youth they are almost excusable—wine, women, and upscale luxury. All this will be his, provided he observes the admonition to leave the last candle unlit. Abdallah gets his desired change of wardrobe and interior decoration, a slew of servants at his beck and call, and a whole harem of gently seductive lovelies. With these ladies he enjoys a modest dancing orgy until, in drunken abandon, he lights the forbidden candle and is reduced to his former impoverished state, having lost his true love as well. Needless to say, matters are patched up in the final act, with the sheik playing deus ex machina to ensure that the happily reconciled couple begins married life with a lavish dowry and that the scolding mom-in-law is removed from the scene via a trap door concealed by a curtain of flame.

The dancing was capable throughout and, in several cases, particularly distinguished, from the crystal-clear execution of young Tobias Praetorius, playing an impudent little slave boy, to the technical aplomb and ingratiating personality of Morten Eggert in the title role. Among the women, Yao Wei, recently made a soloist, seemed to have taken it upon herself, single-handed, to revive the “type” of the nineteenth-century Bournonville ballerina. She looks like an exquisite porcelain figurine brought to life, precise and delicate in her movement, sweetly shy in her personality. Born and trained in China, she’s the perfect example in a company that now, of necessity, includes many non-Danes, of the fact that Bournonville dancing is not the exclusive province of the “natives.” It can also be mastered through an affinity that is aesthetic—perhaps spiritual as well.

How the Danes bring this production off, I don’t know. Thinkers and sophisticates would surely dismiss it as idiotic. The story is trite and not rendered particularly magical in this telling. The moral weight Bournonville managed to invest in even the slightest, most frivolous subjects (as in his King’s Volunteers on Amager) is absent here—in part, perhaps, because Abdallah has not yet been enriched by decade after decade of dancers putting themselves into the roles. What’s more, the streams of enchaînements, taken together, are nearly stultifying, though any one solo, duet, quintet—even single choreographic phrases—may be ingenious, exciting admiration and pleasure. It’s just that it’s impossible to watch that much of that sort of thing; the eye simply flags. And yet the company—with its indefatigable quicksilver feet, its charm, and its unforced communal desire to please—does bring it off, making you feel, even as your good sense is crying out, “Enough! Enough!,” that you’ve somehow been delighted.

For the record: The score, by Bournonville’s most frequent musical collaborator, H.S. Paulli, will sound strangely familiar at times, even to audience members new to Abdallah. Hans Beck, the RDB’s ballet master from 1894 to 1915, appropriated stretches of it to add variations to the cascade of ebullient dancing already present in the celebratory closing act of Napoli—another instance in which—though it’s heresy to say it, I suspect less might have been more.

Photo: Martin Mydtskov Rønne: Morten Eggert and Haley Henderson in August Bournonville’s Abdallah

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Digterens Teaterdromme: H.C. Andersen og Teatret (The Poet’s Theater Dreams: Hans Christian Andersen and the Theater) / Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Den Sorte Diamant (Royal Library, The Black Diamond), Copenhagen / March 11 – October 22, 2005

Digteren og Balletmesterens Luner: H.C. Andersens og Bournonvilles Brevveksling (The Caprices of the Poet and the Ballet Master: The Correspondence of Hans Christian Andersen and August Bournonville) / Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Den Sorte Diamant (Royal Library, The Black Diamond), Copenhagen / June 2005

Europaeeren Bournonville: En udstilling om balletmesteren, kunstneren og åndsmennesket (Bournonville—the European: August Bournonville—ballet-master, choreographer and theorist) / Stærekassen, Copenhagen / May 30 – June 12, 2005

The indefatigable research librarian Knud Arne Jürgensen has mounted no fewer than three exhibitions in connection with the bicentennial celebration of the birth of August Bournonville and Hans Christian Andersen, colleagues in art and friends as well.

The most comprehensive—and enchanting—of these shows is Digterens Teaterdromme: H.C. Andersen og Teatret (The Poet’s Theater Dreams: Hans Christian Andersen and the Theater) at The Black Diamond, the ultra-modernistic branch of the Royal Library, an immense, thrusting black glass shape that seems to cleave space to look out over the water.

The most comprehensive—and enchanting—of these shows is Digterens Teaterdromme: H.C. Andersen og Teatret (The Poet’s Theater Dreams: Hans Christian Andersen and the Theater) at The Black Diamond, the ultra-modernistic branch of the Royal Library, an immense, thrusting black glass shape that seems to cleave space to look out over the water.

It goes without saying that Andersen is best known for his stories. (If you don’t know the great ones in their original form, stop reading this article immediately, please, and go to here for The Ice Maiden or here for The Snow Queen. The simpler tales—The Ugly Duckling, The Little Match Girl, even The Red Shoes—that you met with when you were very young consisted, in all likelihood, of dumbed-down “retellings.”) But Andersen succumbed to the lure of the theater very early in his childhood and aspired to become part of that world, which he considered, quite simply, a realm of magic and ecstasy. To this end, he made various attempts to take his place in it through acting and dancing, though performance was clearly not his métier. More fittingly, he wrote for it, eventually with considerable success. In the course of these efforts, he collaborated with Bournonville on several occasions.

Jürgensen, who characteristically operates in an orderly, thoroughgoing mode, has arranged the wealth of his chosen material in distinct categories. These begin, most usefully, with a survey of the theater, both classical and popular, in Andersen’s time (in other words, the world Andersen hoped to enter) and photographs of the creative and interpretive artists who inhabited it. Then we see—through manuscripts, programs, the writer’s irresistibly ingenuous sketches, and the like—Andersen’s own creations for that world. The Andersen-Bournonville connection is brought to life through letters the two exchanged, ballet libretti and scores, costume designs, actual costumes, photographs of executed scenography, and—best of all—toy theater set-ups. The obligatory personal objects belonging to Andersen are also there for the ogling—the ivory paperknife, the porcelain inkwell in the form of a ship—though I must say I find the small “daily” possessions of dead artists a macabre (or is it ludicrous?) means of invoking them. For me, the most revealing item among these artifacts was Andersen’s personal photo album. It’s occupied not by images of family or ordinary friends from assorted trades and professions, as are your album and mine, but by portraits of the artists, dead or living, whom he considered his soul mates. If all this weren’t enough, there is the pair of human-height panels from a folding screen that Andersen collaged and that he gazed at from his bed in the last year of his life. Called “Childhood” and “Theatre,” the panels are haunting studies of Andersen’s singular vision of those aspects of his being. Freud would have had a field day with them.

One needn’t travel to Copenhagen before October 22 to relish this treasure trove of material. The armchair traveler need only go here to experience it close-up and in astonishing detail. He or she should be sure to seize the opportunity the site offers to enlarge the images, which are so well photographed they seem uncannily real—telling, in the manner of Andersen himself, an extraordinarily vivid and resonant tale.

The genius of this exhibition, experienced in situ, is that it takes a multitude of small objects that need to be looked at closely, one after another (a surefire recipe for tedium), and creates for them a world—one that reflects Andersen’s unique imagination—in which they can cohere. Jan de Neergaard, a well-known designer for the stage, is its architect. He has fashioned a theatrically dark, compact space and, working with panels pierced with shapes borrowed from Andersen’s fanciful paper-cuttings, has created a fence that separates the familiar reality the visitor is leaving from the intriguing, perhaps slightly dangerous fantasy he’s being tempted to enter. Inside, this wary yet willing guest must thread through cunning half-secret curving passageways, his orientation pleasantly dislocated by a crazy-quilt patterned floor, some of its segments mirrored. Everywhere, the mysterious gloom is illuminated by pinpoint lights that allow him to discover the exhibition’s wonders. At the center of this space lies an improvised theater—an oval with a dozen chairs visitors can shift at whim—where, onscreen, a wise professor with the kindliest voice in the world (think of a grandmother with a Ph.D.) narrates (alas, only in Danish) the marvelous tale of Andersen’s life and achievement. As a whole, this inspired environment suggests a child’s playhouse, where, without forsaking a fragile tether to reality, dreams and illusions may be granted full sway.

Curiously, the biographical tale this show tells reveals an Andersen far happier and self-confident, his career unfurling in a calm, logical, almost inevitable course, than the Andersen contemporary scholarship portrays—with its early miseries, its continuing frustrations and self-doubt. In many ways, this halcyon picture relates to Mit Livs Eventyr (published in English translation as The Fairy Tale of My Life), the autobiography the poet, for so we must call him, wrote to portray himself as he wished the world to see him. Both views of Andersen, of course—the full spectrum of wretchedness to ecstasy—are there for all to see in his stories.

Jürgensen has supplemented this ambitious exhibition with a small—it’s confined to a single wide vitrine—but enticing display called Digteren og Balletmesterens Luner: H.C. Andersens og Bournonvilles Brevveksling (The Caprices of the Poet and the Ballet Master: The Correspondence of Hans Christian Andersen and August Bournonville). The title is a play on Amor og Balletmesterens Luner (usually translated as The Whims of Cupid and the Ballet Master), the only ballet by Vincenzo Galleotti, the Royal Danish Ballet’s first important choreographer, that the company still performs.

The display samples the exchange of letters between Andersen, the stage-struck storyteller, and Bournonville, the Dane who made the most profound contribution to the realm of classical dancing. The Royal Library holds 59 of the pair’s letters, ranging in time from 1837 to just before Andersen’s death in 1875. In this richly productive period of both artists’ lives, Jürgensen reports, they wrote to each other of matters aesthetic, professional, and personal.

The original manuscripts of three letters are presented here. The sight of them quickens the heart, making all the tales one has heard of the connection between the two artists seem, somehow, truer. The words, handwritten in ink now brown with age, on paper with a highly tactile quality, seems to speak—even if you can’t decipher the elegant nineteenth-century orthography, let alone the Danish language. Though the letters, sadly, aren’t translated here, labels inform us that one of Bournonville’s was composed on the occasion of Andersen’s 62nd birthday, and that the one from Andersen was written when the choreographer was in Vienna in 1856, staging a production of what has become his signature ballet, Napoli. Jürgensen also offers these complementary/complimentary quotations from the correspondence: “You are a poet and I put much in this small word!” (Andersen to Bournonville, 1841); “You interest, entertain, and move. You convince and give strength, one cannot request more from a poet” (Bournonville to Andersen, 1862). Jürgensen has annotated and introduced the complete correspondence for imminent publication by Gyldendal.

The letters are supplemented—in the vitrine and, more extensively, in the book—with several reproductions of Andersen’s intricate, whimsical paper-cuttings that feature ballet motifs. One of them creates two rakish mirror-imaged dancing men in suits, blithely perched on the wings of a tolerant pair of swans. Another shows a proscenium stage seemingly made of cloth, topped with a ghostly hooded human head; it frames a pair of matchstick-limbed ballerinas in Romantic tutus, dancing in the shade of some generic scenographic foliage. One might claim that Andersen was choreographing with his scissors. He himself said, “Cutting out paper, that is the beginning of writing.”

As most of us have discovered, with the Internet’s rabid expansion, there are some things that of necessity used to be experienced in public, and standing up—such as routine shopping—that are actually better accomplished privately, sitting down, in a place and time of one’s choice. Such is certainly the case with Jürgensen’s third exhibition, Europaeeren Bournonville: En udstilling om balletmesteren, kunstneren og åndsmennesket (Bournonville—the European: August Bournonville—ballet-master, choreographer and theorist). It is currently enjoying a brief life as an illustrated text on a group of hanging panels in the lobby of the Royal Theatre’s Stærekassen, a gloomy venue for small productions that is interesting to architecture buffs for its Art Deco style. But it achieves a fuller and more accessible (to say nothing of ongoing) existence not, as with the Theatre Dreams show, on the Internet, which guarantees seemingly eternal life, but in the form of a handsomely produced booklet. This publication, which shares its name with the exhibition, offers an expanded text in both Danish and English (the Stærekassen panels are English-only) and realizes the well-chosen illustrations even more beautifully.