Seeing Things: November 2004 Archives

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, NYC / November 16-21, 2004

I’m having a lot of trouble with Pina Bausch’s work these days. As just about everyone has noted, the German choreographer whose dark and dirty dance-theater extravaganzas were once hailed as marvelously radical, has, in the last decade, been producing pieces that are gentler, tamer, ostensibly more mellow. In the productions with which she made her name in the States in the 1980s, Bausch took the position of a plaintive, damaged witness to a numbingly reiterative existence in which individuals shuffled between melancholy isolation and hostile matings. Gradually, however, she has turned into a proselyter for the possibility, at least, of pleasure, even romantic love. Bausch Lite, folks are calling the present mode.

I found most of the early work loathsome—hardly dancing, conceptually sophomoric, self-indulgent, and dull—but in retrospect I prefer it to Bausch’s mature-phase tactics. When I think back, the early, tediously unpleasant stuff seems to me at least sincere—Authentic Bausch. In the latest work to hit BAM, the 2002 Für die Kinder von gestern, heute und Morgen (For the Children of Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow), some of the old devices—mean and heavily ironic—appear, but mostly as tics, automatic throwbacks to earlier procedures, rather than events that register with the striking vehemence of a mood or idea that goes straight from impulse to metaphor.

An interesting symptom of Bausch’s evolution is the minimizing of the grunge element. In the course of the pieces that made her an art-world celebrity, Bausch could be counted on to produce a filthy, intentionally disgusting stage floor. Dirt, liquids, crazily mistreated food, crushed blossoms—you name it—were routinely smeared, splashed, or strewn on the dancing ground and subsequently massaged into it by treading, flailing, falling bodies. The effect resembled the mess a child makes naturally (or in fits of gleeful misbehavior) with its food or excrement. And of course it referred to the fallout from sex.

Now the housekeeping is immaculate. Even the small puddles of water or the few drifting petals that happen to sully to the pristine white floor in the course of For the Children are neatly picked up or tidily wiped away. Similarly: Bausch’s people originally appeared in garments scavenged from thrift shops—ill-fitting and evocatively downscale castoffs, just right for the savaging they’d get as the action progressed. Now the performers have a costumer, Marion Cito, and the women’s gowns are ravishing. (Each lady sports several changes.) In the Bad Old Days, makeup was largely Hallowe’en Garish and often put to lethal purpose (a guy, say, using lipstick to paint graffiti on the naked back of his female victim). Today, the women are as cosmetically beautified as mannequins readied for a Vogue shoot. Female armpits and legs that went defiantly unshaven are now smooth, and their owners have gone to the trouble, it looks like, to extend their foundation from face and neck to arms and upper torso like a pack of conscientious ballerinas suiting up to play Odette, Queen of the Swans.

Like all of Bausch’s pieces, For the Children proceeds by increments—over nearly three hours. Vignette follows vignette; structure is loose; meaning—even message--remain vague. Some segments, most of them sappy—the full cast pretending to be butterflies or building sand castles—may refer to the dance’s cryptic title, which, I assume with regret, refers to adults’ contacting their Inner Child. Several disjunctive solos depicting a kind of psychic falling apart provide the show’s most eloquent moments. The most bizarre passages include a group of drop-dead glamorous women in black raking parts into their hair with their stiletto-heeled pumps; nasty uses of fire to mutilate clothing, flesh, and, pointedly, a book; plus the customary Bauschian variations on the theme of humiliating courtships and bad sex.

A good part of the show’s second half is devoted to free-for-all dancing—high-octane displays of physical bravado that owe much to break dancing, skate boarding, and the wild improvisatory action that occurs in clubs where the refreshments are mind-bending. The idea seems to be that physical ecstasy equates with psychic triumph or release. Twyla Tharp used this ploy in the “Golden Section” of The Catherine Wheel; the finale of Harald Lander’s Études can be thought of as an early prototype. Bausch’s grand slam finale doesn’t earn what it’s aiming for, though. In no way is it the logical outcome of the events preceding it; it appears to be tacked on, in desperation. Neither can it lay claim to any intrinsic choreographic merit. It looks like raw improvisation, edited only to avoid collisions.

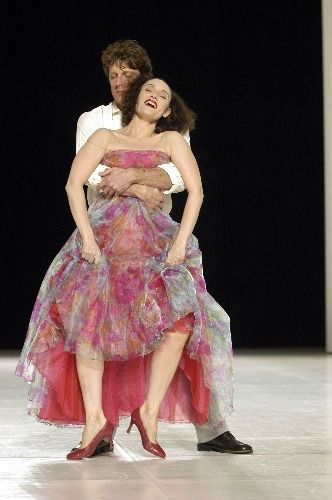

Despite the shift in emphasis in Bausch’s work from acting to dancing, most of the fifteen technically accomplished members of the cast register as distinct personalities. Ditta Miranda Jasjfi, childlike in appearance, is remarkable in her pathos and stubborn resilience, while two veterans—Nazareth Panadero and Dominique Mercy—recall the peculiar, unique force of the old-school Bausch performers. Panadero, with her gravelly voice, her blithe, firm stride, and her vivid self-projection, is primarily neither dancer nor actor but sheer personality. Though she skirts the edge of self-parody, audiences still adore her appetite for life, her nerve, her way with a blood-red lipstick. Mercy is her opposite—mild-mannered and physically unassuming. He makes the most of that recessive quality, operating like an anonymous man in the street, wrapped in a thoughtful, slightly troubled, inner-directed air. Invariably, he’s cast as a person to whom things happen, not one who initiates events. His secret ace? His tremendous dignity; it pervades everything he does. Mercy’s best moment in For the Children—more telling even than his pair of quietly riveting man-at-the-end-of-his-rope solos—finds him clad in nothing but a supersized tutu; instead of a fig leaf, there’s this huge cloud of chiffon fluff. He crosses the stage in this absurd outfit, his manner entirely uninflected, wielding one of those French galvanized-tin watering cans, as if to sprinkle the dance floor, as the youngest “rat” of the Paris Opera did, to prevent skidding accidents, in a time immortalized by Degas. Not an iota of Trockadero-style comedy intrudes into this strange small escapade; Mercy makes it all grave beauty.

Photo: Stephanie Berger: Nazareth Panadero with Pascal Merighi in Pina Bausch’s Für die Kinder von gestern, heute und Morgen

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Works & Process at the Guggenheim: Balanchine Continued . . . at Ballet Arizona / Guggenheim Museum, NYC / November 14 and 15, 2004

The first program in a series of four exploring the ongoing life of George Balanchine’s legacy showcased Ib Andersen, one of the most glorious of the Danish male dancers who “defected” to the New York City Ballet to be part of that incomparable choreographer’s world, and nine dancers of Ballet Arizona, where he is now artistic director.

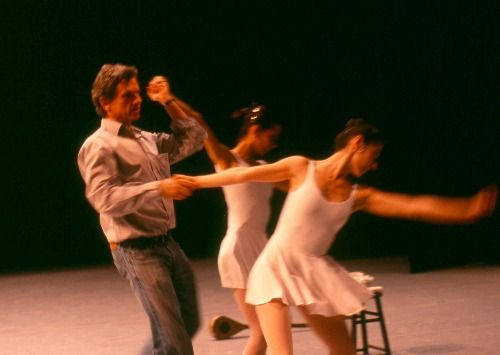

With the company’s permission, I watched early afternoon class the day of the first performance. On a chilly stage, on a floor that was sticky in some places, slippery in others (these flaws would be corrected by curtain time), without musical accompaniment, Andersen put his dancers through their paces. Despite these less than favorable circumstances, it was evident that he has been managing, very effectively, to transmit key principles of the Balanchine style. The dancers’ work was brisk and clean; its goal seemed to be execution that is eloquent in its very stripped-down efficiency. Refusing the decoration or sentimentality that can prettify the classical vocabulary but inevitably smudges it, this way of working lets the step speak for itself.

Once the dancers moved from the barre to the center of the space, they revealed, in addition to swiftness and clarity, a sculptural dimension as well as a welcome individuality of physical type and temperament. This last made me recall the New York City Ballet of the fifties, when the company, of necessity, harbored a more variegated range of dancers than it does today, with a limitless talent pool available to it.

Like Balanchine before him, Andersen is a man of few words in class. He doesn’t explicate and he doesn’t exhort. He sets the steps—in canny, challenging combinations—watches keen-eyed, and corrects sparingly, matter-of-factly, and unerringly. Under his aegis, I imagine, one could learn quite a lot.

Andersen’s own choreography, seen in the evening’s performance, is another matter. On a single viewing, I found it baffling. He presented solos and duets drawn from a lengthy work, Mosaik, each excerpt to music from a different composer, and segments of Elevations, to Handel. With few exceptions, this choreography is simply not dancey. For whatever reason, Andersen chooses not to do what the music is saying, even dictating. Despite the allurements of the score, his choreography remains aloof, disengaged. It has other agendas, it would seem, but at first glance they’re unfathomable.

Much of the choreography is adamantly spare, and its steps or small clusters of steps refuse to connect. One thing is done, then another. Then another. To what purpose? one keeps wondering. And why the pauses in the action that are like pockets of dead air? A few of the dances seem to be very brainy, comments on the music rather than an emanation from it, or reflections on a “concept.” The Mosaik solo to some upbeat Rossini, for instance, charmingly danced by Astrit Zejnati, might be a deconstruction of bravura work. Another solo from the same piece, to which Joseph Cavanaugh brought admirable gravity and weight, suggested the half-life of a god sculpted in stone. But ideas don’t dance with much alacrity; indeed, they’re inclined to stasis.

When it comes to theme, Andersen seems to be preoccupied with isolation, alienation, estrangement—that is, with people remaining distanced even when they are coupled, with action that thwarts the body’s natural impulse toward coordination and flow. The results include perverse lifts and entanglements and an atmosphere dismayingly devoid of vitality.

All of this seems to contradict the dancer he once was: musical; lyric; a quicksilver athlete; a creature of the air, buoyed, it always appeared, by an ecstatic vision; a performer who had located his rightful artistic home.

The program offered two Balanchine items: the sublime adagio from Divertimento No. 15, which is danced by five couples who appear in sequence, like poignant but fugitive images amplifying the transcendent beauty of Mozart’s music, and the duet from Slaughter on Tenth Avenue.

The Mozart ballet was beautifully done, the dancing profoundly musical and filled with delight. The women, in particular, aimed for the kind amplitude that once—but, alas, no longer—made NYCB audiences weep in response to the sight and sound, perfectly combined, of ineffable beauty. Their cavaliers provided careful, sympathetic support. Everyone, despite individual limitations of anatomy and talent (blessings so cruelly rationed by the gods), rose to the occasion with an elegance of bearing that spoke of classical dancing’s aristocratic roots and a purity of intent that has become all too rare. This is the sort of mass transformation that only excellent artistic direction—based on taste, vision, and endless labor in good faith—can bring into being. The dancers were Lisbet Companioni, Michael Cook, Nancy Crowley, Paola Hartley, Natalia Magnicaballi, Kendra Mitchell, Elye Olson, and Zejnati.

The rendering of the Slaughter duet was, to my mind, diminished by a dimension lacking in its dancers. Magnicaballi and Cook, both fine as far as they went, didn’t go far enough into the realm of raw—adult—sensuality. They seemed to be a pair of teenagers astonished to find they’ve fallen crazily in love, like the appealing adolescents in a Robbins ballet. This lightweight reading is not what Suzanne Farrell (in whose company Magnicaballi dances) used to give us.

In between the segments of dancing, Andersen was interviewed by Lourdes Lopez, a former principal dancer at the New York City Ballet who is now executive director of the Balanchine Foundation. She is a perfect ambassador for dance, combining a keen intelligence with a gracious manner. She elicited from Andersen, who used to be shuttered in interviews, thoughtful comments on his handling of the Balanchine legacy and a vivid picture—frank, warm, and tinged with Danish irony—of his position as artistic director of a small company operating far from the hubs of classical dancing.

Here are a few fragments of their conversation—as accurately as I could record them on the fly:

IA, commenting on an amateur film Lopez screened that showed him at his fleetest, rehearsing one of the Mozartiana variations choreographed for him, with Balanchine applauding him at the finish: He used what I could do then.

IA, on Balanchine: Dancing his ballets was an education of how to be in life.

IA, on staging Balanchine’s ballets: I teach the steps and I teach what I think his intent was. It’s what I think he intended, which is of course not [necessarily] what he intended. And, like everyone else who stages Balanchine’s ballets, I put something of myself into it—because what else can you do?

LL: What do you think Balanchine wanted to see [in dancing]?

IA: Expressive bodies.

IA, on his position with Ballet Arizona: Arizona is pioneering country. A lot of people there don’t know much about dancing. Some do, but a lot don’t. You give that audience what it wants, and then you give them something that challenges them. I’m lucky enough to have shaped my own environment there. (Half joking) I tell the board of directors what they should think.

LL: (Laughing) That’s the Balanchine legacy in a nutshell.

Photo: Harrison Hurwitz: Ib Andersen in rehearsal at Ballet Arizona

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Mandance Project / Joyce Theater, NYC / October 21 – November 7, 2004

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, as the French say. The more things change, the more they remain the same. The proverb might have been generated to describe Eliot’s Feld’s choreographic career. Feld’s latest company, Mandance Project—consisting of five men and a lone woman—recently made its debut in New York with a repertory of 11 dances, all but one of them brand new. Astonishingly, the work looks like much that Feld, a huge but inexplicably stymied talent, has been doing for the last quarter-century. The pieces—six of them on the program I saw—are typically astutely crafted but rigid, confined, and obsessively repetitive. The very antithesis of early Feld works like Intermezzo and At Midnight, they say no to organic flow and depth of feeling, substituting aren’t-I-clever? gimmicks for the qualities that lie at the heart of expressive dancing.

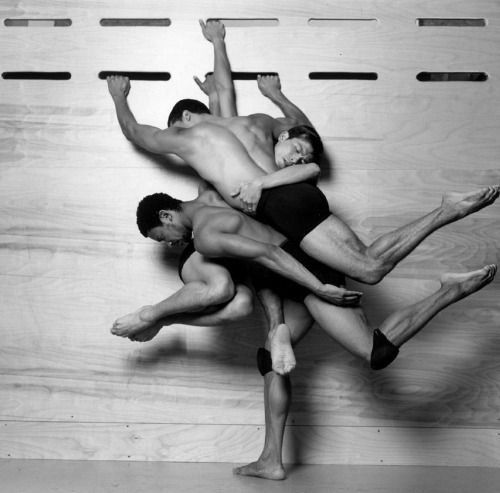

In Backchat, a trio of ballet boyz climbs up, down, and over a free-standing made-to-look-like-brick wall over and over again, performing the athletic feats of neighborhood thugs in picturesque formations. The wall is only  some 10 feet wide and stands in a vast field of empty stage space, but the three guys remain attached to their prop as if they were shackled to it. It’s not long before the viewer feels shackled too. Granted, Feld wants his audience to feel for these tough yet vulnerable guys; after all, he made his Broadway debut as a teenager in West Side Story. So he allots them a “dream” sequence in which they buddy up in slow motion (“Somewhere there’s a place for us”) and finishes by having them hang upside down from the top of their wall like victims of an atrocious crucifixion. Why, then, does he devote the bulk of his effort to making them look like a video commercial for athletic shoes?

some 10 feet wide and stands in a vast field of empty stage space, but the three guys remain attached to their prop as if they were shackled to it. It’s not long before the viewer feels shackled too. Granted, Feld wants his audience to feel for these tough yet vulnerable guys; after all, he made his Broadway debut as a teenager in West Side Story. So he allots them a “dream” sequence in which they buddy up in slow motion (“Somewhere there’s a place for us”) and finishes by having them hang upside down from the top of their wall like victims of an atrocious crucifixion. Why, then, does he devote the bulk of his effort to making them look like a video commercial for athletic shoes?

In Proverb, the young, sensuous, intensely concentrated Sean Suozzi is stripped to his flesh-tinted jock strap, a pair of Prodigal Son sandals, and lights that he cradles in his palms. These provide what seems to be the only illumination on the stage. At one point, he seems to hold the world’s last spark of fire in his hand; elsewhere the gigantic, blurry shadows he casts on the backdrop threaten to engulf him. Much like similar Feld undertakings, this hackneyed business goes on far too long after it has made whatever point it’s going to make.

Rumors has three men and a woman in s&m black webbing hanging from metal hooks upstage, like meat in a butcher shop window. We peer at them through a downstage row of gleaming jointed metal rods that seem to have some industrial—possibly lethal—purpose. When finally (and not a moment too soon), the figures free themselves and enter the clear available space centerstage, they thrash and droop like a quartet of tortured Petrouchkas, each rooted to his or her individual spot. The finale allows them a measure of locomotion—which they employ to crash noisily through the curtain of rods—but then re-condemns them to their hooks. The suggestion of human atrocities sits ill with the chic look of the dance. Admittedly, this incompatibility has been popular for some time. Did it come to the dance stage via fashion photography or is it merely a sign of these dismal times? Rumors gives you all the time in the world to ponder this question.

A Stair Dance, a tribute to Gregory Hines (and, surely, a couple of older legendary tappers), sets five dancers on five abutting five-step staircases and—guess what?—sends them up and down. Also, in the belated fullness of time, around. Jiving on the steps, the dancers might be notes on a musical staff. The accompanying music is by Steve Reich, a composer to whom Feld frequently turns, almost as if he were using Reich’s repetition, which usually results in a freeing ecstasy, as an excuse for his own iterative compulsions. These, however, are more likely to make viewers feel as if they’ve been sentenced to an indefinite term in a box that keeps (very, very slowly, mind you) getting smaller and more devoid of oxygen.

Yazoo, originally created for Mikhail Baryshnikov, is an endless series of shenanigans with a Western twang, beautifully performed by Wu-Kang Chen. Jawbone, beautifully performed by Damien Woetzel, is yet another one of those Feld experiments in how long you can keep a dancer interesting onstage without material that has any intrinsic interest. Feld, with his exaggerated estimate of that length, has, over the years, reduced far too many superb performing artists to choreography that’s the equivalent of reading aloud from the phone book.

The dancers chosen for the Mandance Project (note the company name’s reference to Baryshnikov’s White Oak Project, with its implication of impermanence) deserve richer material. Nickemil Concepcion, Jason Jordan, and the alluring Patricia Tuthill were the standouts of Feld’s now disbanded Ballet Tech (and trained from the start in its innovative school). They, along with the equally outstanding Chen, hold their own with Woetzel, a veteran New York City Ballet principal, and Suozzi, who has been with NYCB for four years without that company’s yet recognizing his true worth. Mandance makes them look like six dancers in search of a choreographer.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Photo © Bruce Weber 2004: Studio photograph, uncostumed, of Jason Jordan, Nickemil Concepcion, and Wu-Kang Chen in Eliot Feld’s

Backchat.Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary