Seeing Things: March 2004 Archives

Stephen Petronio Company / Joyce Theater, NYC / March 23-28, 2004

The press release for Stephen Petronio’s latest creation, The Island of Misfit Toys, being given its first New York showings at the Joyce, promised “themes that include obsession, guilt, insatiable desire and the mundane details of life.” The night I went, the crowd seemed wary—baffled perhaps—and gave it a lukewarm reception. C’mon, what’s not to like?

The press release for Stephen Petronio’s latest creation, The Island of Misfit Toys, being given its first New York showings at the Joyce, promised “themes that include obsession, guilt, insatiable desire and the mundane details of life.” The night I went, the crowd seemed wary—baffled perhaps—and gave it a lukewarm reception. C’mon, what’s not to like?

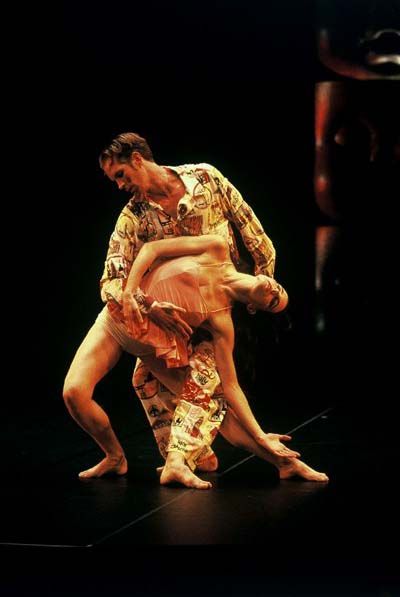

For some eloquent London critics writing at its premiere last year, the piece epitomized the downtown New York Zeitgeist—all glamorized dysfunction, decadence, and desperation. As with the solo Broken Man and City of Twist, two works from 2002 that shared the Joyce program (called “The Gotham Suite”), Toys proves Petronio to be a canny practitioner of a genre I’ve come to think of as KinkyChic. And, as is his wont, the choreographer has enlisted big names to bolster the edgy quality he lays claim to. The score is drawn from Lou Reed numbers; the set comes from Cindy Sherman; the costumes, from Imitation of Christ’s Tara Subkoff.

What’s not to like? Well, I have two complaints, both of them serious. One: Petronio substitutes fashion (not just clothes, but lifestyle, to use a relevant trash word) for meaning and feeling. Two: The dancing he devises—while executed with stunning fluidity, speed, and strength—is extremely limited in vocabulary, rhythmic interest, and structure. Not surprisingly, Toys is most telling in occasional images that would make reasonably potent shots in a latter-day glossy.

Sherman sets the scene with a pair of grotesque doll-like sculptures that loll on the apron of the stage, one huge-bellied with extra limbs and two pin-heads, the other with a gigantic head that sports a gaping hole where the face should be. Later she projects a totem pole of baby faces onto the backdrop. Each is rendered as a plump infant-Buddha mask, its impassivity distorted by fear, delight, rage, or grief. The visages evoke horror because, contrary to popular wishful thinking about the sweetness and innocence of the very young, people six months old really look like this as they experience primal emotions with unalloyed force. This photographic collage struck me as being the single genuine element in the show.

As the piece opens, Petronio—head shaved, sleek body outfitted in menacingly weird evening dress—lolls in a chair, back to the audience, smoking as he scrutinizes a bunch of figures with unreliable spines. He might be a PoMo Diaghilev auditioning prospects for his company. But, as if in a wannabe reference to E.T.A. Hoffmann’s riveting tales of the subhuman, the hapless dolls—creations, perhaps, of the Petronio character’s own imagination and ingenuity—come to half-life and wrest away his power.

The balance of the piece chronicles the gradual disintegration of the dolls—pajama-clad bodies inclined to mildly depraved sexual practices and an increasing impairment of their sense of center. As their physical coordination diminishes, they lose harmony, eloquence, purpose—in other words, the traits, based on connection, that define civilized beings. The dehumanization process goes on at a length that could only hold the attention of a voyeur, and I think Petronio casts his audience in that role. He doesn’t elicit empathy for, or even understanding of, the creatures in his garish, disjunctive parade; he offers the stuff up merely as titillating entertainment. Oddly enough, his inventions aren’t strong or singular enough to fill the bill.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Photo credit: Angela Taylor: Gino Grenek and Jimena Paz in Stephen Petronio’s The Island of Misfit Toys

Johannes Wieland / 92nd Street Y Harkness Dance Project at The Duke on 42nd Street, NYC / March 10-14, 2004

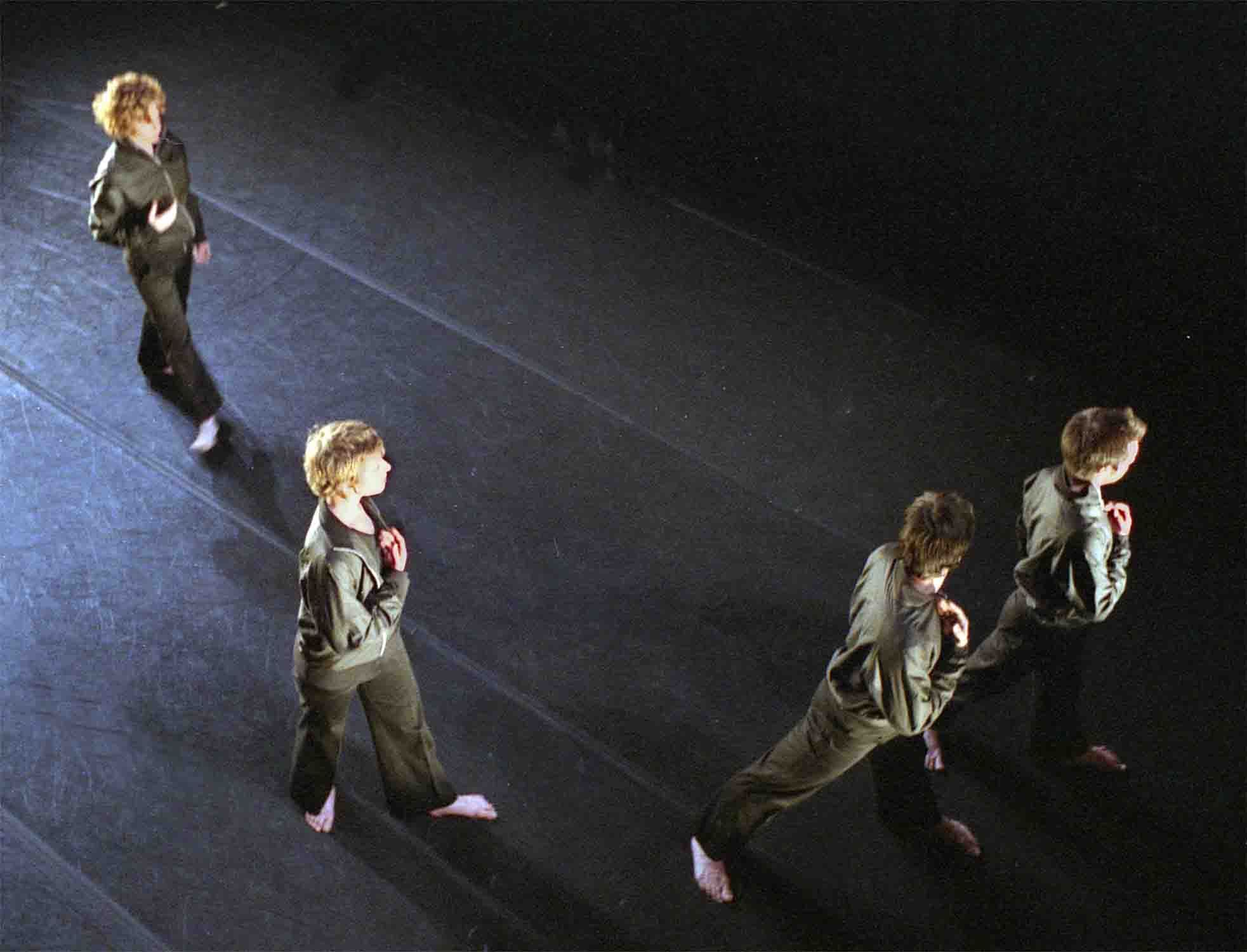

When Johannes Wieland operates in his signature style, he makes dances that are immaculately pared down and aggressive to the point of violence. Adamantly abstract on its surface, the work is haunted by subtle currents of emotion. His best achievement to date in this vein in the new Membrane, for eight black-clad dancers in a black-box void, only their faces, hands, and bare feet luminous as the moon in a midnight sky.

The figures are outfitted identically in jerseys, trousers, and windbreakers. Those chest-hugging zip jackets, though, are as much prop as costume. And they evolve, as the action develops, into a metaphoric skin—tough but capable of being shed or penetrated—that encloses and isolates the individual, cloaking his vulnerability to the effect of others, thwarting real connection.

The piece opens with a prologue of sorts. The man and woman who will prove to be the central couple (Julian Barnett and Eliza Littrell) maneuver each other into and out of their jackets, twisting and twining like a pair in a rubber-jointed circus act. Then the rest of the cast galvanizes into movement—sudden, powerful, and raw—that makes you think of gang warfare. Repeatedly, one dancer flings another’s weight around his body, finally positioning the partner high on his shoulders. The ploy suggests that their roles have abruptly reversed, slave becoming master, victim becoming terrorist.

The dancers group into duos, trios, quartets that reveal Wieland’s inventive command of structure. (He actually makes good on his press materials’ lofty declaration that he employs “an architecturally driven understanding of bodies, movement, and space.”) One trio, replicated by another in greater shadow, has dancer A supporting dancer B in a burly grasp so that B, predatory legs scrambling in the air, can tread up and down dancer C’s body as C stands riveted in place, stoically tolerating the repeated aggression. Then Wieland adds the two remaining cast members, who’ve stood immobile on the outskirts of the scene, like bystanders at a horrific event who can’t stop watching but do nothing to intervene or turn their backs, stonily refusing the role of brother’s keeper. And at this moment Wieland exercises his true gift. He gets you to quit admiring his organizational acumen and feel what a tough world these figures (indeed, all of us) inhabit, physically and psychologically. He has you walking right down those mean streets.

Eventually the dancers shed their windbreakers, and much is made of the stripping (usually at another’s hand) and of the garment stripped, which the owners continue to animate—viciously flinging it about, nuzzling it like a child with his “blankie”—even though they’re no longer wearing it. The shedding of the protective shell and the ensuing ridding the self of it—so that it’s not merely gone from the wearer’s back, but no longer in his possession--leads only to more violence, which builds to a frenzy. So much for the romance of attaining maturity.

In what you might call a coda, the dance refocuses on the main couple, now alone in the gloomy arena. Having, with the greatest difficulty and effort, laid themselves bare, they reap no reward. Instead, they’re consigned to continue their hard-won togetherness in a void of endless inconsequential repetition, treading in an amorphous space with no destination. It’s a suitable latter-day ending for a latter-day condition. Wieland neither sentimentalizes nor overdramatizes it. This calibrated reticence is a key aspect of his talent. He need only beware that it doesn’t stifle him.

Occasionally Wieland ventures into modes quite different from the one Membrane epitomizes. Another new piece, Filtrate, uses three distinct generations of dancers; eerily lit Plexiglas boxes that serve as cages for the participants; and an absurdist text involving a freezer, memory, and ice cubes. For the first third of its 27 minutes, while I was still making my best effort to scrutinize it, I found it inscrutable. After that, I found it affected and dull. But, though I would never willingly watch this piece again, I’m not railing at Wieland for making it. Like ordinary folks, choreographers have to explore paths that may lead them to swampland, even quicksand, in order to get where they’re really meant to go.

Photo credit: Sebastian Lemm: Isadora Wolfe, Eliza Littrell, Branislav Henselmann, and Julian Barnett in Johannes Wieland's Membrane

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Jonathan Burrows/Matteo Fargion / The Kitchen, NYC / March 11-13, 2004

Is less more? Answer: Yes, when we’re talking about Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion’s Both Sitting Duet. Performing the 45-minute piece they invented, the two guys sit on battered regulation-issue wooden chairs smack in the middle of a bare, black-box stage space. The chairs are congenially angled toward each other, as if set up for conversation. The men, who have a certain physical resemblance, are early middle-agers with compact bodies and keen, worn faces. Their costume—no-nonsense jeans, nondescript shirts and shoes—is the epitome of ordinary. You’d pass them on any urban street without a second look.

Each man has, at his feet, a notebook scrawled with words and symbols that he eyeballs regularly, as a musician does his score. Fargion is a musician; Burrows, a ballet-trained dancer and choreographer. Shortly after they’ve launched into their 45-minute tour de force of arm and hand jive, you can tell from their movement—even though they’re executing the same gestures in unison, in canon, or as rapid-fire Q & A—who comes from which art. Burrows’s execution is the more sharply focused, projected toward a presumed spectator. Fargion’s, with its softer edge, seems inner-directed, has a slightly more subtle rhythm. Burrows powers his arms from his gut, while Fargion operates mainly from the shoulder, his midsection lax.

Here’s what they do: shake their hands wildly in front of their chests, so their fingers look like sparklers; use one hand to count the fingers of the other with a child’s deliberation, as if the answer might be in doubt; stroke their palms along their trousered thighs; palpate the floor with their fingertips; curl their fingers into vivid mudras that yield no explicit meaning; extend their arms in semaphore signals or (Burrows alone, while Fargion softly claps out a tempo) classical ports de bras.

A couple of times they stand up for a few seconds, even go so far as to turn in place, repeating a raucous cry; once they shift the position of their chairs so that one lies in the other’s shadow. Such departures from what they’ve set up as the parameters of the piece have the impact of high drama—violent and haunting.

Most of the time they remain seated, their movement largely confined to their arms and hands, torso and head just going along for the ride. They make a lot of eye contact, though, and run through a gamut of facial expressions that suggest a ping-pong exchange of ideas and a brotherly relationship that’s both challenging and complicit.

Will you believe me if I tell you this wasn’t tedious? Far from it. Just the opposite. The more things remained, so to speak, the same—one man’s move copied by the other, a single gesture repeated again and again by both—the more fascinating the whole business became. The secret—an open one, to be sure—lies foremost in the small, canny variations in rhythm with which the performers inflect each unit of basic material. Example: Delivering a rapid three-gesture phrase for one hand, the pair begins by working in unison, then lets its individual articulations go slightly out of synch in a loop that keeps returning to the original unison and departing from it again. It’s like the hypnotic action of windshield wipers with a slight glitch in their mechanism.

Another part of the secret: The repertory of moves is adeptly structured, alternating between the small and the large, the fierce and the delicate, the agitated and the serene, the sounded (slaps, claps, pats, occasional stomps or monosyllabic cries) and the silent. In the silence—the piece has no conventional musical accompaniment, and the audience was rapt—the very scratching of a reporter’s pen on her notepad seems an intrusion.

And then, rewarding one’s alertness, there’s the message (you might even call it the moral) of the piece: A close focus on replication paradoxically allows differences to emerge, minute states of otherness growing immense in scale or suggestive power.

Here's what Both Sitting Duet made me think of: Pairs of Parisian intellectuals, sitting in cafes, exchanging abstruse ideas for the fun of it. My uncles hunched over a card table, playing infinite games of pinochle at my grandmother’s house, every Sunday afternoon of my childhood. Deft practitioners of American Sign. Obsessive-compulsives. Language teachers demonstrating the gestures that accompany voluble Italian. Merce Cunningham.

Photo credit: Herman Sorgeloos: Jonathan Burrows (left) and Matteo Fargion in their Both Sitting Duet

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

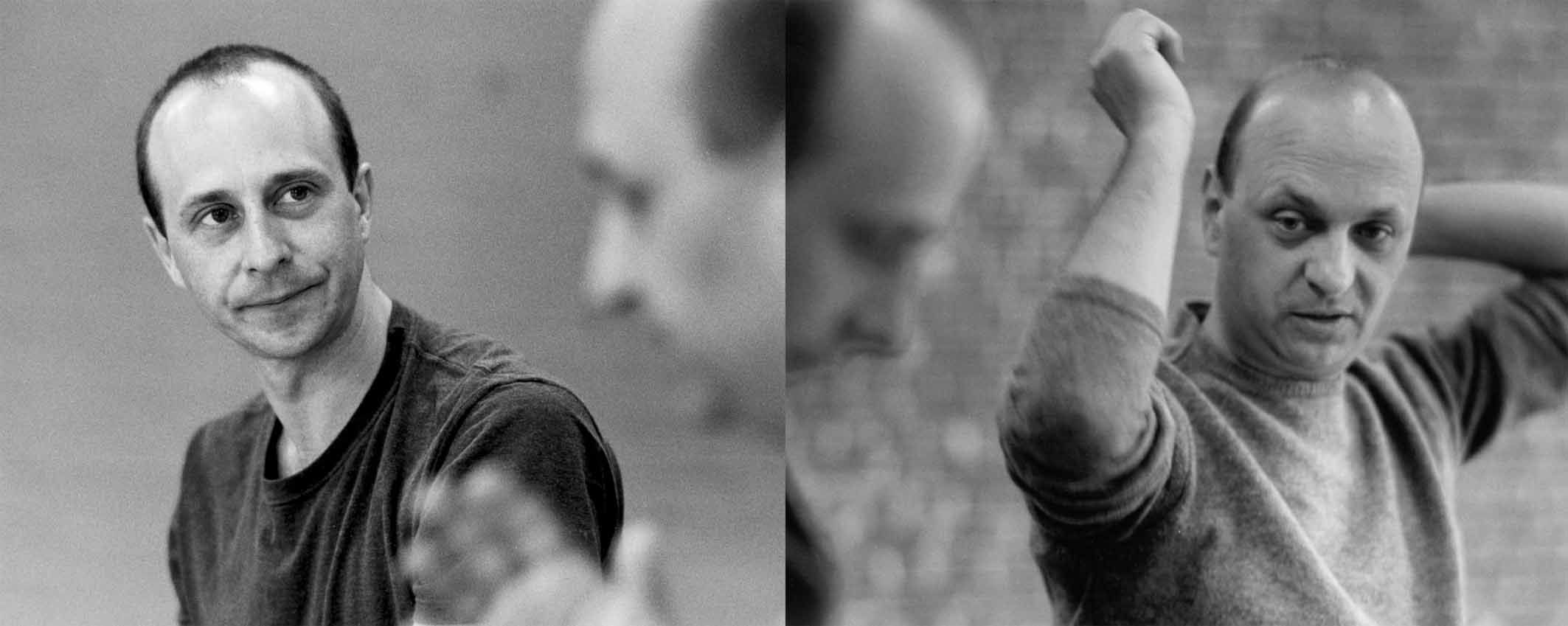

Nederlands Dans Theater / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, NYC / March 9-14, 2004

Come to us from The Hague and holding forth at BAM for the first time since 1999, Nederlands Dans Theater has changed while the New York audience wasn’t looking. For over a quarter century, it has been shaped by Czech choreographer Jirí Kylián, long its artistic advisor and still chief provider of its repertory. But, judging from Program A (a trio of Kylián works from the last two years), with which the group opened its weeklong run, the choreographer has abandoned the rooted-in-the soil-eyes-on-the-stars mode in which he forged his reputation for the sex-cruelty-and-angst-as-gorgeous-visuals realm that we know best from high-end fashion photography of the last decade.

The accompanying sound scores, all by Dirk Haubrich, punctuate white noise with brief, startling intrusions. This aural element only exacerbates the fact that the Kylián’s stage pictures are so tightly controlled as to leave one’s muscles twitching spasmodically from the relentless tension. I have neither the time nor the patience to return for Program B, which promises: yet another recent Kylián; Symphony of Psalms, to allow comparison of the old style with the new; and a single piece by another choreographer, which may or may not prove that the door is open a crack. Details follow on what I did see.

27’ 52”, named for its duration—a fact high-handedly left unmentioned in the house program—actually seems to take place in a photographer’s studio. The space is bare and dark except for two elements: floor cloths and hanging drop cloths (essentially moving walls) of heavy white plastic, like those camera folk use to reflect the artificial illumination they so closely control, and the high-power light fixtures themselves, which recall prison searchlights. The place (for which Kylián takes a “décor concept” credit in the program) is, in other words, nowhere—without landmarks, without character, without evidence that nature even exists. The spiritual equivalent of such a vacuum is familiar to the clinically depressed.

Six dancers—three men, three women—venture into this bleak arena and proceed to disport themselves in various physically impressive, theatrically ominous ways to prove that love doesn’t stand a chance. A relationship that’s already fraught is hardly improved by an extra man who, in the guise of photographer’s assistant, functions as a potential rescuer turned betrayer—and a voyeur. Coupling, postmodern style, has abandoned any claim to privacy, you see; intimacy lies in the public domain. One woman meets her male partner in fighting mode—lash out even before you say hello is the greeting style here—and they segue into agitated unison and mirror-image stuff. Is this the postmillennial way of bonding?

Antipathy, fury, victimization prevail. The women bear the brunt of the last, predictably; Kylián has never displayed much empathy for the female of the species. Finally we see one couple stripped to the waist—Adam and Eve?—who engage in something that, chez Kylián, may qualify as tenderness, though it reads equally as mutual manipulation. In the end the woman tries to flee from her guy, gives in, lets him wrap her in a floor cloth that morphs into shroud, thinks better of this and escapes, spies the “assistant” at the far end of the cloth and runs to him, only to have him shroud her while the first guy shrouds himself, the cloth turned to its reverse side, which is—you guessed it!—black. So, stretched cross-stage, we have this flat black tarmac with body bags at either end. The remaining drops fall from above with ominous thuds. I hope the dancers are getting danger money.

I don’t mind Kylián’s underlining the fact that human connection is a tough business. What I chafe against is his presenting defeated love as a given, without alternatives, and, moreover, as glamorous and therefore desirable. Reiterated, this take on the subject is not merely arid, it’s boring as hell. Maybe it is hell.

Last Touch, the most ambitious and compelling piece on the program,  offers an interior lavishly draped in dust sheets and a sextet of inhabitants in Joke Visser's heady gloss on Victorian dress, whose interpersonal proclivities, largely erotic, are similarly veiled. At first the people are almost as still as figures in a wax museum, suspended in a living death. When they finally begin to move, their animation is frail and sporadic; as it’s defined in this piece, dance lies somewhere between stasis and slow motion.

offers an interior lavishly draped in dust sheets and a sextet of inhabitants in Joke Visser's heady gloss on Victorian dress, whose interpersonal proclivities, largely erotic, are similarly veiled. At first the people are almost as still as figures in a wax museum, suspended in a living death. When they finally begin to move, their animation is frail and sporadic; as it’s defined in this piece, dance lies somewhere between stasis and slow motion.

It takes several long minutes for the eager if

hesitant man in the doorway to creep up behind the lusciously ripe virgin who’s absorbed in a book, place his hands over her eyes—Guess who, my pretty one!—and tip the rocking chair in which she’s cradled so far backward, her head almost touches the floor. All the succeeding ploys follow the same pattern of dilatory invasion of private domains with covert cooperation at the receiving end, reluctance simply augmenting the delights of desire.

The exquisitely retarded advance to orgasm—which is, finally, achieved, three couples simultaneously, and marked by a raucous outburst in the score and the burning of the book—that advance, as I was saying in this seemingly endless sentence, is made all the more delectable by the fact that the women are swathed in miles of fabric. The effect is, if you can excuse the word, ravishing. The conventions of the negligee, the wedding gown, and widow’s weeds—fantasy genres in themselves—are here allowed a surreal dimension. The dust sheets are transformed into bed sheets with which the gentlemen screen, wrap, and caress their ladies, while the ones covering the floor, rippling like creamy waves, spill off the front of the stage toward the spectator’s lap, as if inviting a little interactive play.

My favorite moment in the piece? The Repressed Spinster/Wicked Witch/Mrs. Danvers woman’s kissing the candle flame that will ultimately ignite the book. It goes pretty much unnoticed, though, in the thick fog of psychological paralysis that shields the neurotic figures in this strange pantomime from any reality that might call for forthright and vigorous action. Like opting for a simple yes or no.

None of this is new. In dance, Martha Clarke has done it several times over, with more edge. And, God knows, she has not been alone. Ultimately, though, the mode derives from literature, from those marvelous novels of suffocating erotic obsession: Benjamin Constant’s Adolphe, which no one, regrettably, reads anymore; Choderlos de Laclos’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses, which is still read and relished—or at least enjoyed in its movie version; and Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa, which has essentially been relegated to university curricula for English majors. Last Touch fails, in the end, because it can’t or won’t avail itself of the novels’ resources: words, characters, plot. The dance is merely titillating spectacle, defeated by its self-indulgent combining of tortoise pace with injudicious length.

Serving as the program’s curtain raiser, Claude Pascal (a name invented by Kylián to signify something he elects not to explain in the house program) has all the trademarks of the choreographer’s latter-day style: a sleek, stark décor, here with swiveling mirrored panels; elegant, stylized period (here Edwardian) costume contrasted with subtly sexy practice clothes; an enigmatic text in more than one language; an eerie, ominous atmosphere in which the beautiful is doomed to come to no good; bodies honed to perfection only to be put to ambiguous purpose. The costumed passages are duly absurdist; the pure dance passages, charged with disaffection and anomie. Much of this mishegaas is new to Kylián, but dance fans on several continents, having been subjected to it for some time, may not need to have their dancing served up with lines like “When you switch off the light, you see only the inside of yourself.” On second thought, they may find them oddly applicable to the choreography at hand.

Photo credit: Stephanie Berger: Paula Sánchez and Václav Kunes in Jirí Kylián's Last Touch

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Paul Taylor Dance Company / City Center, NYC / March 2-14, 2004

Paul Taylor's current two-week run at the City Center reveals the company in splendid form, dancing as if an ardent, intensified study of echt Taylor style had reanimated it. Old and recent masterworks-Aureole, Airs, Piazzolla Caldera, Promethean Fire-look reborn. And you can spend an enchanted evening focusing on any one of three stellar women: the veteran Silvia Nevjinsky, who has acquired a new softness, calm, and sculptural dimension; Annmaria Mazzini, who follows in the line of Ruth Andrien and Kate Johnson as the girl everyone adores; and Michelle Fleet, a more recent addition to the troupe, who is instantly recognizable as the Next Great Thing. The fact that the two new choreographic offerings were non-events-flops, to put it bluntly-is almost beside the point.

Le Grand Puppetier, being given its world premiere, takes off from Fokine's Petrushka, a key work in the dance canon created in 1911 for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, which starred Vaslav Nijinsky in the title role of the puppet who proves to have an immortal soul. Ingeniously, Taylor uses Stravinsky's pianola version of the score he created for the Fokine ballet. Then, confusingly, Taylor junks Fokine's libretto, while appropriating some of Fokine's characters, so that viewers familiar with Petrushka will be driven to distraction by the matches and mismatches, while viewers unacquainted with the Fokine are likely-Taylor's plot being improbable and pointless-to remain in the dark. Why, they may well wonder, is the Emperor, as Taylor calls his Puppet Master, bent on marrying off his daughter to a gay fop? Is it likely that the Emperor's pathetic Puppet would (1) overthrow his master's tyrannical regime and, (2) having done so, cede control back to the dictator?

Le Grand Puppetier, being given its world premiere, takes off from Fokine's Petrushka, a key work in the dance canon created in 1911 for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, which starred Vaslav Nijinsky in the title role of the puppet who proves to have an immortal soul. Ingeniously, Taylor uses Stravinsky's pianola version of the score he created for the Fokine ballet. Then, confusingly, Taylor junks Fokine's libretto, while appropriating some of Fokine's characters, so that viewers familiar with Petrushka will be driven to distraction by the matches and mismatches, while viewers unacquainted with the Fokine are likely-Taylor's plot being improbable and pointless-to remain in the dark. Why, they may well wonder, is the Emperor, as Taylor calls his Puppet Master, bent on marrying off his daughter to a gay fop? Is it likely that the Emperor's pathetic Puppet would (1) overthrow his master's tyrannical regime and, (2) having done so, cede control back to the dictator?

Taylor's Emperor, dressed in a jet version of Napoleonic uniform, may be Fokine's Charlatan, earning a living by displaying his puppets (just possibly human slaves) to a cruel audience in the market square. On the other hand, he may be: God; the autocratic Diaghilev; the founder-leader of a dance company that exists to dance that great master's choreography (Taylor himself, perhaps); or one or another of the powerful guys dominating the news of late, who operate according to the conviction that they have the right to control how people should live (and die).

Such a puppeteer may be even worse than evil. Writing of his retirement from performing after chronic physical woes caused his collapse on stage, Taylor notes in his autobiography, Private Domain, "Once in a while it seems sad, but most times it seems comical. Our dance god, the Great Puppeteer up there in the flies, that ineffable string snipper, turned out to be an old-time prankster."

The best thing in this excursion is the figure of the Puppet, played soulfully by Patrick Corbin, who evokes the photographic evidence of Nijinsky's portrayal of Petrushka. Costumed in white, like a commedia dell'arte clown, Corbin is pitiably limp and disjointed, fatally pure and innocent. Taylor's cleverest move in this piece is to have the Puppet led around, often dragged, on a long-reined leash attached to a noose-like collar. The initiated will recall another character on display in Fokine's crude, raucous marketplace-the trained bear.

Taylor's riff on Fokine also includes a subterranean stream of comment on homosexuality. It takes the form of the misalliance of the fop in lavender regalia and the Emperor's minxish daughter as well as the daughter's cavorting with her soldier paramour, not simply for their mutual lustful pleasure but to torment the Puppet. Balletomanes will recall the fact that Nijinsky was Diaghilev's lover for a time, before a conniving woman came between them. Still, all the diverting speculation about who represents what in Le Grand Puppetier fails to conceal the fact that nothing interesting is going on dancewise.

A second new work, being given its local premiere, fared no better, though it was more fun. "In the beginning," as the Good Book tells us, "God created the heaven and the earth." For In the Beginning, his own typically idiosyncratic account of Creation and its consequences, Taylor takes a Classic Comics view, rendering the proceedings with simplistic, amusing charm. For musical accompaniment he's borrowed from Carl Orff's Carmina Burana (of all things!) and Der Mond. Santo Loquasto has provided him with natty Middle Easternish costumes and a series of backdrop projections in childlike style of the relevant geography, fruit trees, doves, and rainbow (though the choreography supplies neither ark nor flood).

Taylor's Jehovah starts out as an Old Testament God, a strict parent who, having created the human race, is prone to rage at its inevitable transgressions. Then, with a quick shift of wardrobe from black to white, as the piece skips blithely to literature's greatest sequel, he (He, if you will) evolves into an icon of forgiveness. The hands that were all wrathfully pointing fingers now relax to deliver blessings from palm to gratefully bowed heads.

Adam and Eve are multiples. Taylor, no mean creator himself, produces no fewer than four of each, with a matching plethora of apples. A fifth woman, listed in the program as an Eve, turns out to be Lilith, apocryphal but tempting as hell, who relishes her job of luring the others into an orgy of group sex. Their paradise lost, naked and ashamed, scared and sorrowful, our first ancestors produce a horde of offspring. (Well, how else would the world have been peopled?) With the agonies of childbirth duly documented-in caricature mode, of course-Cain and Abel pop out first. In a matter of seconds, these large, hairy neonates go from fetal position to thumbsucking to a sibling rivalry that begins in normal boys-will-be-boys roughhousing and ends (as you may have heard), very, very badly.

Finding nothing more pertinent to do, the rest of the population engages in some innocuous Israeli folk dancing, at which point Jehovah reappears. It being in his job description, he throws an irate-power tantrum strangely reminiscent of some megalomaniac solos in the repertory of the redoubtable Martha Graham, with whom Taylor once danced. Chastized, humanity duly wanders, faltering, in the desert-in a crossover before a thorny front cloth. And then-by some theatrical or spiritual miracle that leaves you saying "huh?"-the beleaguered wanderers find themselves reinstated in God's grace. As a curtain line, the tableau seems premature.

Taylor has done terrific work before with stock stories-in the 1983 Snow White (which boasts an unforgettable apple) and the 1980 Sacre du Printemps-and, indeed, with Bible stories, as in that crazily ambitious failure, the 1973 American Genesis. In the Beginning shows little evidence of ambition, just as it yields little rigor, little substance, and little resonance. But if this piece is slim, it's still entertaining-silly and touching by turns, with brief moments and maverick insights that furnish clear evidence of genius.

Photo credit: Paul B. Goode: Members of the Paul Taylor Dance Company assembled for Taylor's Le Grand Puppetier

2004 Tobi Tobias

Paul Taylor Dance Company / City Center, NYC / March 2-14, 2004

Paul Taylor’s current two-week run at the City Center reveals the company in splendid form, dancing as if an ardent, intensified study of echt Taylor style had reanimated it. Old and recent masterworks—Aureole, Airs, Piazzolla Caldera, Promethean Fire—look reborn. And you can spend an enchanted evening focusing on any one of three stellar women: the veteran Silvia Nevjinsky, who has acquired a new softness, calm, and sculptural dimension; Annmaria Mazzini, who follows in the line of Ruth Andrien and Kate Johnson as the girl everyone adores; and Michelle Fleet, a more recent addition to the troupe, who is instantly recognizable as the Next Great Thing. The fact that the two new choreographic offerings were non-events—flops, to put it bluntly—is almost beside the point.

Le Grand Puppetier, being given its world premiere, takes off from Fokine’s Petrushka, a key work in the dance canon created in 1911 for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which starred Vaslav Nijinsky in the title role of the puppet who proves to have an immortal soul. Ingeniously, Taylor uses Stravinsky’s pianola version of the score he created for the Fokine ballet. Then, confusingly, Taylor junks Fokine’s libretto, while appropriating some of Fokine’s characters, so that viewers familiar with Petrushka will be driven to distraction by the matches and mismatches, while viewers unacquainted with the Fokine are likely—Taylor’s plot being improbable and pointless—to remain in the dark. Why, they may well wonder, is the Emperor, as Taylor calls his Puppet Master, bent on marrying off his daughter to a gay fop? Is it likely that the Emperor’s pathetic Puppet would (1) overthrow his master’s tyrannical regime and, (2) having done so, cede control back to the dictator?

Le Grand Puppetier, being given its world premiere, takes off from Fokine’s Petrushka, a key work in the dance canon created in 1911 for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which starred Vaslav Nijinsky in the title role of the puppet who proves to have an immortal soul. Ingeniously, Taylor uses Stravinsky’s pianola version of the score he created for the Fokine ballet. Then, confusingly, Taylor junks Fokine’s libretto, while appropriating some of Fokine’s characters, so that viewers familiar with Petrushka will be driven to distraction by the matches and mismatches, while viewers unacquainted with the Fokine are likely—Taylor’s plot being improbable and pointless—to remain in the dark. Why, they may well wonder, is the Emperor, as Taylor calls his Puppet Master, bent on marrying off his daughter to a gay fop? Is it likely that the Emperor’s pathetic Puppet would (1) overthrow his master’s tyrannical regime and, (2) having done so, cede control back to the dictator?

Taylor’s Emperor, dressed in a jet version of Napoleonic uniform, may be Fokine’s Charlatan, earning a living by displaying his puppets (just possibly human slaves) to a cruel audience in the market square. On the other hand, he may be: God; the autocratic Diaghilev; the founder-leader of a dance company that exists to dance that great master’s choreography (Taylor himself, perhaps); or one or another of the powerful guys dominating the news of late, who operate according to the conviction that they have the right to control how people should live (and die).

Such a puppeteer may be even worse than evil. Writing of his retirement from performing after chronic physical woes caused his collapse on stage, Taylor notes in his autobiography, Private Domain, “Once in a while it seems sad, but most times it seems comical. Our dance god, the Great Puppeteer up there in the flies, that ineffable string snipper, turned out to be an old-time prankster.”

The best thing in this excursion is the figure of the Puppet, played soulfully by Patrick Corbin, who evokes the photographic evidence of Nijinsky’s portrayal of Petrushka. Costumed in white, like a commedia dell’arte clown, Corbin is pitiably limp and disjointed, fatally pure and innocent. Taylor’s cleverest move in this piece is to have the Puppet led around, often dragged, on a long-reined leash attached to a noose-like collar. The initiated will recall another character on display in Fokine’s crude, raucous marketplace—the trained bear.

Taylor’s riff on Fokine also includes a subterranean stream of comment on homosexuality. It takes the form of the misalliance of the fop in lavender regalia and the Emperor’s minxish daughter as well as the daughter’s cavorting with her soldier paramour, not simply for their mutual lustful pleasure but to torment the Puppet. Balletomanes will recall the fact that Nijinsky was Diaghilev’s lover for a time, before a conniving woman came between them. Still, all the diverting speculation about who represents what in Le Grand Puppetier fails to conceal the fact that nothing interesting is going on dancewise.

A second new work, being given its local premiere, fared no better, though it was more fun. “In the beginning,” as the Good Book tells us, “God created the heaven and the earth.” For In the Beginning, his own typically idiosyncratic account of Creation and its consequences, Taylor takes a Classic Comics view, rendering the proceedings with simplistic, amusing charm. For musical accompaniment he’s borrowed from Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana (of all things!) and Der Mond. Santo Loquasto has provided him with natty Middle Easternish costumes and a series of backdrop projections in childlike style of the relevant geography, fruit trees, doves, and rainbow (though the choreography supplies neither ark nor flood).

Taylor’s Jehovah starts out as an Old Testament God, a strict parent who, having created the human race, is prone to rage at its inevitable transgressions. Then, with a quick shift of wardrobe from black to white, as the piece skips blithely to literature’s greatest sequel, he (He, if you will) evolves into an icon of forgiveness. The hands that were all wrathfully pointing fingers now relax to deliver blessings from palm to gratefully bowed heads.

Adam and Eve are multiples. Taylor, no mean creator himself, produces no fewer than four of each, with a matching plethora of apples. A fifth woman, listed in the program as an Eve, turns out to be Lilith, apocryphal but tempting as hell, who relishes her job of luring the others into an orgy of group sex. Their paradise lost, naked and ashamed, scared and sorrowful, our first ancestors produce a horde of offspring. (Well, how else would the world have been peopled?) With the agonies of childbirth duly documented—in caricature mode, of course—Cain and Abel pop out first. In a matter of seconds, these large, hairy neonates go from fetal position to thumbsucking to a sibling rivalry that begins in normal boys-will-be-boys roughhousing and ends (as you may have heard), very, very badly.

Finding nothing more pertinent to do, the rest of the population engages in some innocuous Israeli folk dancing, at which point Jehovah reappears. It being in his job description, he throws an irate-power tantrum strangely reminiscent of some megalomaniac solos in the repertory of the redoubtable Martha Graham, with whom Taylor once danced. Chastized, humanity duly wanders, faltering, in the desert—in a crossover before a thorny front cloth. And then—by some theatrical or spiritual miracle that leaves you saying “huh?”—the beleaguered wanderers find themselves reinstated in God’s grace. As a curtain line, the tableau seems premature.

Taylor has done terrific work before with stock stories—in the 1983 Snow White (which boasts an unforgettable apple) and the 1980 Sacre du Printemps—and, indeed, with Bible stories, as in that crazily ambitious failure, the 1973 American Genesis. In the Beginning shows little evidence of ambition, just as it yields little rigor, little substance, and little resonance. But if this piece is slim, it’s still entertaining—silly and touching by turns, with brief moments and maverick insights that furnish clear evidence of genius.

Photo credit: Paul B. Goode: Members of the Paul Taylor Dance Company assembled for Taylor's Le Grand Puppetier

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary