Seeing Things: January 2004 Archives

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

George Balanchine (Mr. Neoclassicism) did time on Broadway and in Hollywood and—always one to rise cheerfully and inventively to the particular nature of an occasion—produced some fetching work for the popular theater. As a souvenir of those ventures, the New York City Ballet’s Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration offered the Slaughter On Tenth Avenue ballet he made for On Your Toes. Jerome Robbins, NYCB’s No. 2 choreographer, may well have been in his most congenial element on Broadway. Think of his dances for West Side Story and The King and I; remember that On the Town grew from his evergreen ballet Fancy Free. So it’s not incongruous that the company should have invited Susan Stroman (Ms. Broadway) to create a program-length showpiece for NYCB to premiere on the day after Balanchine’s 100th birthday. Maybe there’s even a message (or an omen) here—“This is the first day of your second hundred years, George. Enjoy!”

Peter Martins, the NYCB’s artistic director, frankly told an interviewer for the New York Times that he wanted the Stroman work because it will sell tickets. I’m baffled by this artistic policy. Is Double Feature, as Stroman’s two-part creation is called, a fund-raising device to support the company’s more balletically inclined work? Or is it supposed to lure its audience back to the New York State Theatre for an evening of Balanchine and Robbins, Martins and Wheeldon? Using an annual six-week run of The Nutcracker—for loot and luring purposes makes sense. The Stroman venture does not. The Nutcracker, in Balanchine’s unbeatable version, is a real ballet that happens to have achieved a crazy degree of popularity. The part of the audience that goes to see it because it has become a winter- solstice ritual gets to see a classical ballet and may be tempted see others. The logical equivalent of what the audience for Double Feature sees would be another flashy, overmiked Broadway show.

Peter Martins, the NYCB’s artistic director, frankly told an interviewer for the New York Times that he wanted the Stroman work because it will sell tickets. I’m baffled by this artistic policy. Is Double Feature, as Stroman’s two-part creation is called, a fund-raising device to support the company’s more balletically inclined work? Or is it supposed to lure its audience back to the New York State Theatre for an evening of Balanchine and Robbins, Martins and Wheeldon? Using an annual six-week run of The Nutcracker—for loot and luring purposes makes sense. The Stroman venture does not. The Nutcracker, in Balanchine’s unbeatable version, is a real ballet that happens to have achieved a crazy degree of popularity. The part of the audience that goes to see it because it has become a winter- solstice ritual gets to see a classical ballet and may be tempted see others. The logical equivalent of what the audience for Double Feature sees would be another flashy, overmiked Broadway show.

As its title indicates, Double Feature is a two-part deal inspired, if that’s the word, by silent films. “The Blue Necklace” is a melodrama—about a hoofer who abandons her illegitimate infant, becomes a movie star while the babe grows to nubility (much put upon by a nasty foster mom), and reclaims her daughter once the maiden is recognized through her genetically determined gift for dancing. “Makin’ Whoopee!” is a melocomedy based on the play that inspired the movie Seven Chances, starring Buster Keaton, who could elevate slapstick to a divine plane. The plot concerns a fellow too shy to propose to his sweetheart, who eventually gets his gal after severely farcical circumstances offer him dozens of brides at once, a horde of ravening white-skirted wilis, many of them played by gentlemen of the ballet en travesti. In the hands of another choreographer, the material co-opted for Double Feature might provide opportunities for charm and good fun. Stroman, however, is largely immune to such mild enticements and opts for dazzling cleverness that is all bright, tough surface, like the finish of an exceedingly expensive car.

Knock-your-eyes-out ensemble numbers, with their escalating energy, are what Stroman does best. Granted, her big ballroom scene looks embarrassingly vacant in a repertory where “ballroom” is defined by La Valse, Liebeslieder Walzer, and Emeralds. But the chorus line of femmes in sheer black tights that opens the show and the rushing flock of wannabe brides that closes it are duly effective. The way it’s set up, though, Double Feature depends on lots of intimate vignettes to tell its tales, and it’s here that Stroman reveals her lack of a large and subtle imagination. Either she dreams in clichés or thinks her audience does and cannily gives them what she believes they want. This is an example, in little, of the way American commerce works. Ballet, being esoteric, used to be somewhat immune to it.

Stroman uses the classical ballet vocabulary—and some of its sleekest executants—like a youngster fascinated with a fabulous new toy. Oddly, though she deploys them with a lavish hand, she can’t make the steps add up to dancing. Except in the rawest ways, they serve neither plot nor character; they’re not even interestingly connected. And of course dancers trained to the highest level of balletic achievement, steeped in a repertory requiring just that, lack the gustiness—the texture, the grasp of the lowdown—that makes the Broadway gypsy unique, indeed indispensable to popular theater.

The score for Double Feature is a medley of eternally engaging songs by Irving Berlin and Walter Donaldson that are barely recognizable shorn of their lyrics and souped-up by the “original” (I’ll say!) orchestrations of Doug Besterman and Danny Troob. On the other hand, the stylized sets by Robin Wagner and the costumes by William Ivey Long—fittingly in black, white, and sepia—prove to be the best part of the show.

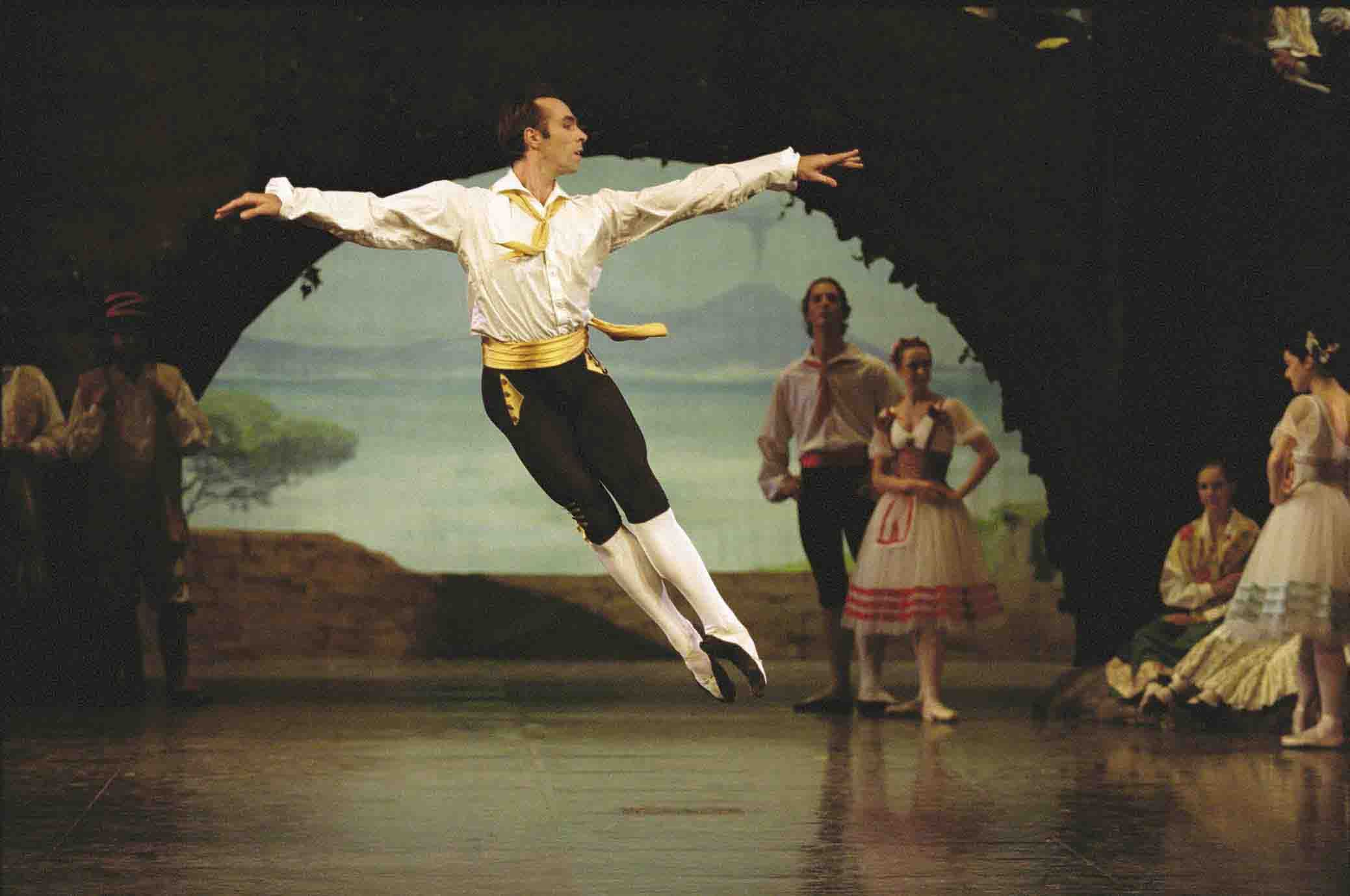

The large cast, including children from the School of American Ballet and a trained dog, did their best under circumstances essentially unsuited to what they are—either by nature or nurture. The pervading enthusiasm made me think of Balanchine’s comment on a another occasion: “This was not high art, of course, but we tried to do it merrily and professionally.” In “The Blue Necklace,” Kyra Nichols danced the mean mom with great (albeit misplaced) emotional sincerity, as if she’d wandered into the Tudor repertory. Damian Woetzel, as the Guy of Her Dreams, transformed his crudely pyrotechnical solo, endowing it with grace, wit, and Astairean charm. In “Makin’ Whoopee!,” Tom Gold fell short of the sweet pathos required of the hero, but Alexandra Ansanelli was delectable as his intended, though given very little to dance. Albert Evans shone in a secondary role, being an ideal crossover dancer, every bone in his body theatrical.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Tom Gold and company in "Makin' Whoopee!" from Susan Stroman's Double Feature

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Royal Danish Ballet / Kennedy Center, Washington DC / January 13-18, 2004

Frank Andersen, artistic director of the Royal Danish Ballet, has a mission. In a campaign that will climax with the 3rd Bournonville Festival in Copenhagen, June 3-11, 2005, celebrating the 200th anniversary of the great Danish choreographer’s birth, Andersen is aiming to make August Bournonville’s ballets vivid to the contemporary viewer who may not instinctively find them accessible and appealing.

Last fall, Andersen entrusted Nikolaj Hübbe (an RDB alum known best as a principal dancer in the New York City Ballet) with the responsibility for a new staging of Bournonville’s best known work, La Sylphide. I reviewed the production at its first performances in Copenhagen, where it was given with Harald Lander’s surefire crowd pleaser, Etudes. The repertory for the RDB’s recent week-long engagement at Kennedy Center, comprised this La Sylphide program and the three-act Napoli, often referred to as the Danish ballet’s calling card.

As its name suggests, Napoli is set in the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius—hence, perhaps, the volcanic temperament of its characters—and mixes the exuberant mime of this population with lusty folk dancing as well as classical dancing in both its poetic and bravura modes. The ballet tells a love story—among common folk, rather than the highborn favored by much 19th-century ballet—with its only to be expected contretemps and an untypical, for the period, happy resolution. (Bournonville’s optimistic outlook is one of his charms).

As its name suggests, Napoli is set in the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius—hence, perhaps, the volcanic temperament of its characters—and mixes the exuberant mime of this population with lusty folk dancing as well as classical dancing in both its poetic and bravura modes. The ballet tells a love story—among common folk, rather than the highborn favored by much 19th-century ballet—with its only to be expected contretemps and an untypical, for the period, happy resolution. (Bournonville’s optimistic outlook is one of his charms).

Napoli is filled with the choreographer’s vivid recollections of his Italian travels, recorded in his memoirs, My Theatre Life. The ballet’s first and third acts take place in a seaside market square (the hero, Gennaro, is a fisherman) that is flooded with sunlight and, on occasion, suddenly accosted by violent storms. The haunting second act occurs in the Blue Grotto of Capri, understood in the ballet as an underwater dream world (read realm of the id) only faintly illuminated by the moon. (Of this hypnotic locale, with its phosphorescent-blue water, Bournonville wrote: “How mysterious is the atmosphere, which suddenly takes away the thought of everything that has delighted—or offended—one in the outside world.”) Here Gennaro and his beloved Teresina, faithful Christians like the rest of their community, now lulled by forgetfulness of the real world with its principles and responsibilities, encounter demons of the irrational. These take the form of the powerful triton king, Golfo, and his band of naiads, whom he holds captive in a life of thoughtless (essentially erotic) pleasure. Teresina and Gennaro escape from the Blue Grotto’s temptations, which test their virtue and their free will, but only just.

Given what Andersen is trying to do—and what ballet director today is not intensively cultivating his audience?—it’s no wonder the current staging of Napoli is somewhat souped up. The opening panorama, a tour de force that presents a bustling crowd pursuing more than a dozen different agendas, is just a shade pushed—and perhaps a shade too rapid as well. Throughout the first act, the rush and the exaggeration undercut the calm, the sweetness, and the ingenuousness that have traditionally been typical of the way the RDB dances its Bournonville. Still, the staging, credited to Anne Marie Vessel Schlüter, Eva Kloborg, Dinna Bjørn, and Frank Andersen, is blessedly devoid of the newfangled “concepts” that plague many a contemporary approach to golden oldies. And the Danish dancers come through with their typical ability to take things personally, making their mime phrases “readable” and their dancing not merely a display of (often dazzling) technical accomplishment but also a communication between the dancer and dancer, as well as dancer and audience.

Several of the dancers in the two casts I saw gave extraordinary performances, and it was their interpretations, more than the production per se, that thrilled me. Tina Højlund, a perfect Teresina, is, to my mind, the most naturally talented woman in the company. Unfortunately she hasn’t had a steady stream of major roles to showcase and develop her gifts. Whether this is the company’s fault or her own or both, I can’t say, but when she’s allowed a major assignment, she can be sheer heaven.

Her dancing is everywhere fluid and graceful, given resonance by a sensuous weight. She never freeze-frames poses, like arabesques, which dancers are prone to dwell on as if they were turning their bodies into pieces of sculpture. Højlund dances through such shapes. Even more uncannily, she makes traveling steps—a high floating jeté, for instance—look like traveling, not steps, in other words, not discrete units that she has been painstakingly perfecting since she was a child, but simply an aspect of ongoing free-form locomotion.

Højlund’s acting has a similar flow and naturalness, its emotional rhythm a cousin to the rhythms of the dancing. If Teresina’s adventures seem to be happening to a real young woman, the reason lies in Højlund’s registering her feelings in every phrase. These feelings—delight, annoyance, jealousy, exasperation, tenderness, fear, sexual attraction, indecision, confusion, devout (almost desperate) faith in a protective Madonna—surge and ebb like the waves of the sea. They all belong to Teresina, they’re all expressed as parts of a single personality, but each changes the character’s personality for a moment, making her as authentic as someone you love.

Magically, none of Højlund’s dancing or acting looks as if she had been taught to do it. It looks like natural behavior. This is almost unheard of in classical ballet, and it is as pleasurable to witness as it is rare.

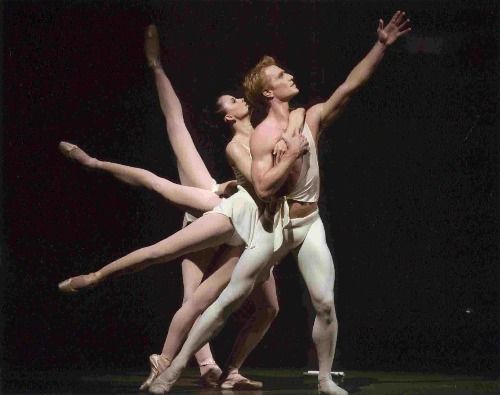

When Thomas Lund makes his entrance as Gennaro, in a huge sailing leap that charges through the assembled crowd straight down the middle of the stage, opening his arms in a wide curve as if to embrace the audience, he seems to be saying, “Here I am. Love me.” The appeal—all invitation, no ego—is impossible to resist, though Lund has neither the looks nor the build classical dancing prefers for its hero roles. Of course it would be wonderful if he had the physical glamour of gorgeous-to-die dancing Danes like Erik Bruhn, Henning Kronstam, Peter Martins, and Arne Villumsen. The gods, alas, are not always so generous.

that charges through the assembled crowd straight down the middle of the stage, opening his arms in a wide curve as if to embrace the audience, he seems to be saying, “Here I am. Love me.” The appeal—all invitation, no ego—is impossible to resist, though Lund has neither the looks nor the build classical dancing prefers for its hero roles. Of course it would be wonderful if he had the physical glamour of gorgeous-to-die dancing Danes like Erik Bruhn, Henning Kronstam, Peter Martins, and Arne Villumsen. The gods, alas, are not always so generous.

Lund earns his hero status sheerly through his dancing. Early in his career, he revealed himself to be a consummate stylist in the Bournonville technique—a master of the speed, clarity, buoyancy, and energy concealed as delight that it demands. Of late—thanks, perhaps, to the coaching he received from Nikolaj Hübbe in the new staging of La Sylphide—he has been daring to try matching that textbook perfection with a genuine, full-out expression of feeling.

Lund is not yet (may never be) completely successful in amplifying his interpretation in this way. His rendition of Gennaro’s hysterical monologue when he thinks himself responsible for Teresina’s drowning in the Blue Grotto—a passage akin to Giselle’s Mad Scene—isn’t yet fully realized or grasped as one long cry of despair rather than bite-size morsels of sorrow. But Lund’s acting has become motivated in every detail and it looks genuinely felt. With further thought, creative coaching, additional performances, and—critical for a dancer like Lund—the courage to crash the firewall of decorum, it may yet become entirely convincing.

Lis Jeppesen, who moved into character parts some years ago after an illustrious career in ballerina roles, is beginning to acquire the skills peculiar to her new mode, one of them a sense of weight. She did a swell job as Veronica, Teresina’s volatile, impassioned mom, abandoning herself to wild grief or robust joy according to the circumstances of the moment. And the DC performances indicated that she’s beginning to apply her newfound knowledge to the most challenging of her roles, the witch, Madge, in La Sylphide. Audiences, and critics especially, must learn patience. If it takes ten years to make a classical dancer, it takes the better part of a lifetime to develop a mime.

As Golfo, which can be a thankless role of standing around making power gestures, Peter Bo Bendixen cut a masterful figure. His sheer physical rightness for the role—he’s tall, dark, handsome, and admirably built—takes him a long way, of course, but he offered much more than appearance. His Golfo carefully calibrated his attempted seduction of Teresina on a scale ranging from authoritative domination to a cautious, longing gentleness, and his behavior when it’s clear he’s lost her—to Gennaro, to reality, to sunlight—bordered on the tragic.

Tommy Frishøi, one of the troupe’s senior character dancers, predictably distinguished himself as Fra Ambrosio, the monk who is the focal point in Napoli of Christianity’s belief in the power of good to overcome evil. Frishøi made you see that behind the cleric’s spiritual serenity lies a troubling doubt, and beyond that, a still-hopeful faith. Switching roles the very next day, Frishøi distinguished himself further as the Lemonade Seller, Peppo. Here, in direct contrast to his portrayal of the monk, he created a salacious figure, full of misplaced self-esteem, conniving for the sheer pleasure of making mischief. His face was an animated mask that shifted from one Daumier-like caricature to the next; his every move exuded the joy of making believe.

Frishøi’s performances are likely to be his final ones with the company in the States. He plans to retire at the end of the season—at the unreasonably early age of 63. Some of the company’s most highly evolved character dancers—who specialize in the mime roles that give a unique resonance to Bournonville’s ballets—have soldiered on, their portrayals growing ever richer and deeper, until the mandatory retirement age of 70.

When asked why hale and hearty septuagenarians were not allowed to continue their stage careers with the RDB, one of them, the late Niels Bjørn Larsen—who entered the company’s school at the age of six, served for a time as the company’s artistic director, simultaneously directing the Pantomime Theatre in Tivoli, and was an unforgettable mime—liked to explain, “We old ones have to leave to give a place to the young ones.” I can’t think of a single young one—or for that matter, middle-aged one—currently in the company who could begin to fill Frishøi’s place, who could come anywhere near the combination of realism and soul with which Frishøi infuses his characters. He is not merely irreplaceable, he’s a member of an endangered species. In the January 18th New York Times, Matthew Gurewitsch wrote, “Most full-length [ballets] reach full length by means of endless filler.” If what Frishøi does at Bournonville’s instigation is filler, balletomania is not a passion worth cultivating.

Photo credit: Martin Mydtskov Rønne: (1) Jean-Lucien Massot and (2) Thomas Lund and Tina Højlund, in August Bournonville’s Napoli

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

You are a woodcutter, a swimmer, a football player, a god. —George Balanchine, instructing Lew Christensen, who danced the title role in Apollo at the ballet's American premiere

When I was a child, I never read fairy tales. My mother disapproved of them for the underage, on the grounds that they were frightening. Perhaps she had read her Grimm in an authentic version instead of the watered-down, sweetened pap concocted for kiddies. If so, she was right about the scare factor. The only fairy tale I remember from my childhood was Snow White, courtesy Walt Disney, and it did, indeed, terrify me. What my mother preferred to ignore was the comfort that fairy tales can provide. Their reflection of primal emotions—rage and revenge, horror at the nature of the body and its functions—validates a child’s innermost feelings, reassuring him (albeit subliminally) that he is not a monster and that he is not alone.

But my mother, whose inclinations were decidedly artistic and literary, was not one to let me languish for lack of worthy reading matter. For fairy tales, she substituted classical myths, via Edith Hamilton, whose Mythology, published in 1942, is still widely read. Given the lives and impulses of the gods and goddesses, my mom’s strategy was patently illogical. But I was content with—indeed, enthralled by—the adventures of the divinities and their earthly connections. As a bonus, when I first encountered Martha Graham’s Cave of the Heart, Errand Into the Maze, and Night Journey a decade later, I knew—with a little help from Freud—just what was going on.

Hamilton’s fresh, accessible style makes the gods seem like real people, complete with human flaws and human aspirations, endowed with (doomed to, perhaps) the peculiarities of human temperament. Things happen to them and they cause things to happen—at once inevitably, because of who and what they are, and with a stunning randomness. In Hamilton’s recounting, the adventures and emotions of prodigious beings relate simply and clearly to our own smaller lives.

Balanchine’s Apollo, as the New York City Ballet danced it in the sixties, when I first laid eyes on it, was marked by a similar quality. The choreography creates events that are odd and wondrous, yet believable. A boy is born, emerges from his swaddling clothes a helpless infant, and goes from the condition of an eager, awkward child to that of young manhood just coming into its powers. The account of each stage is a matter of minutes—seconds, even—but the physical depictions are dead-on accurate.

Balanchine’s Apollo, as the New York City Ballet danced it in the sixties, when I first laid eyes on it, was marked by a similar quality. The choreography creates events that are odd and wondrous, yet believable. A boy is born, emerges from his swaddling clothes a helpless infant, and goes from the condition of an eager, awkward child to that of young manhood just coming into its powers. The account of each stage is a matter of minutes—seconds, even—but the physical depictions are dead-on accurate.

Exploring the domain that is his birthright, Apollo strums his lute and, behold, a trio of muses arrives. The strange moves of each, as she describes her assigned terrain, blend the danse d’école with things you might see in the street. The marvel is that none of this appears peculiar or archly contrived. You accept the astonishments of the ensuing proceedings—the shuffling on flat feet, the harnessing of the muses into a troika, the finger-snap shift between waking and sleeping—as being simply the way things are in this world.

As the ballet develops, it charts Apollo’s growing confidence and authority. In his duet with Terpsichore—the mating of music and dance—it takes on aspects of sublimity that climax in the ascent to Mt. Olympus, a picture of serene ecstasy, with Apollo in the lead, one arm raised in a gesture that is part reverence, part aspiration, the muses in a faithful line behind him.

The suggestion of Balanchine’s ballet—that a god is not born fully equipped with his powers, but accedes to them through specific experience—connects the spectator to the myth. It allows him to understand Apollo’s tale as the saga of a soul finding (perhaps simply defining) its identity. In all my early viewings of Apollo—until Balanchine gave the title role to Mikhail Baryshnikov and ruthlessly cut the birth scene and the final epiphany—this atmosphere of ingenuous discovery prevailed, making the exquisite beauties of the dance all the more poignant.

At the first showing of Apollo in the New York City Ballet’s Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration—in the curtailed staging, alas—Nikolaj Hübbe offered an Apollo in the tradition that charts the god’s evolution, giving a performance that I consider one of the finest accounts of the role that I’ve witnessed and one of the most illustrious in his career.

A born actor as well as a richly gifted dancer, Hübbe addresses each segment of the choreography as if it were part of an ongoing story, so that every moment makes dramatic as well as plastic and musical sense. When he’s first surprised by the muses, for example, he flirts with them a little, like a college freshman delighted to encounter so many amazing girls in one spot. Gradually he becomes more authoritative as he awards each the symbol of the art she represents and then deploys them in different formations as if they were exquisitely crafted toys placed at his disposal. In his solo after the muses’ own he displays the aplomb of full manhood.

Apollo’s duet with Terpsichore, in Hübbe’s reading, becomes a grave experimental undertaking, an investigation into what the god of music can achieve or become when mated with the muse of dance. This Apollo’s approach—awed, even humble—yields increasing delights. And, as Hübbe’s interpretation proposes, increasing responsibilities that are burden as well as blessing. By the time he hears the summons to Mount Olympus, the once lighthearted, frolicsome boy has become almost tragic. With this performance, Hübbe joined my private pantheon of Apollos, which includes Jacques d’Amboise (who was present in the audience), Peter Martins, Edward Villella, and Ib Andersen.

Sorry to say, Hübbe was inadequately served by his trio of muses. Yvonne Borree (Terpsichore) was a cipher, as usual; Rachel Rutherford (Calliope) exuded her familiar loveliness and charm, but here it couldn’t cover the weakness of her attack. Jennie Somogyi (Polyhymnia), gorgeously dynamic and clear—she’s one of the most mettlesome dancers the company has ever harbored—made such an extravagant impact, the proportions of the triumvirate looked all askew. Far too often, NYCB casting seems perverse to me. I suppose I should remember that the gods have their reasons.

Postscript: I caught up on fairy tales in my own daughter’s childhood, as she avidly read her way through Andrew Lang’s marvelous collections, so aptly named for the colors of the rainbow.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Nikolaj Hübbe and Yvonne Borree (Rachel Rutherford and Jennie Somogyi obscured) in George Balanchine’s Apollo

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

The Royal Danish Ballet is performing at Kennedy Center, Washington DC, January 13-18, 2004.

Denmark is a very small country compared to Russia, France, England, and America, yet, like those dance superpowers, it boasts a world-class ballet company with a venerable academy attached to it. Danish dancers trained from childhood at the school housed in Copenhagen's Royal Theatre can be identified by particular aspects of technical prowess: an ebullient jump; light, swift footwork; and fluent épaulement. These qualities are their legacy from August Bournonville, the choreographer and ballet master who spent a good part of the nineteenth century shaping the Royal Danish Ballet and its school according to his vision.

Bournonville's ballets, which have remained the backbone of the RDB repertoire, also fostered the dancers' acting prowess, which has been further encouraged by latter-day additions of dramatic ballets to the company's repertoire. Yet while we admire Danish dancers for their technical and theatrical accomplishments, we love them in equal measure for their charm. They fill the stage with warmth, intimacy, and a contagious joy in motion, seeming to dance and mime for one another, at the same time taking the audience securely into their confidence.

repertoire, also fostered the dancers' acting prowess, which has been further encouraged by latter-day additions of dramatic ballets to the company's repertoire. Yet while we admire Danish dancers for their technical and theatrical accomplishments, we love them in equal measure for their charm. They fill the stage with warmth, intimacy, and a contagious joy in motion, seeming to dance and mime for one another, at the same time taking the audience securely into their confidence.

Most prominent among the Danish dancers are the company's stellar men, a good number of whom left the small duck pond--as the Danes, masters of ironic self-deprecation, refer to their country in contrast to the wide world--for careers on the international scene. Among their number are Erik Bruhn, Peter Schaufuss, Peter Martins, Ib Andersen, and Nikolaj Hübbe. Others, of comparable gifts, chose to stay at home: Henning Kronstam, the most soulful of noble princes and a consummate actor; Niels Kehlet, a kamikaze virtuoso and fine character dancer; and the incomparable mimes Niels Bjørn Larsen and Fredbjørn Bjørnsson. This pantheon also includes Stanley Williams, the celebrated RDB instructor who emigrated to the States midway through his career and became arguably the most influential teacher in Balanchine's domain apart from the master himself.

What, I've always wondered, could be the secret of a ballet academy that has consistently produced dancers of this caliber with such a modest number of candidates to choose from?

The school of the Royal Danish Ballet has been in existence since 1770, providing its pupils with their dance training and, since the mid-nineteenth century, their academic education as well, and giving them opportunities to perform in the ballets, operas, and plays that constitute a repertory housed under one roof. Today children are admitted to the school as beginners from ages seven to twelve. (Provision is made for late starters--most often boys--by placing them with their age group and giving them supplementary coaching as necessary.)

First-year pupils are selected by means of a three-stage audition that includes a two- to four-week trial period of daily classes. Students are subsequently weeded out annually in the course of the academy's nine-year program. The winnowing is hard on the youngsters, sometimes tragically so. A faculty member observes, "In our work, there are many tears." Yet it is essential to ensure well-equipped graduates for a tough profession.

At 16, the survivors are apprenticed to the parent company; at 18, if all has gone well, they join it permanently. In recent years, feeder schools have been opened in a pair of outlying cities, Holstebro and Odense, the object being to enlarge the talent pool without wrenching the younger kids from family and home town. Even the main school in Copenhagen is small. This year it has some 65 pupils, 25 of them boys; the apprentice group holds just four young men.

One might assume that the secret of the Danish school lay in a particularly ingenious or efficacious training system. Yet, with certain exceptions, the program now being followed is significantly different from the various methods used in past generations. The late Niels Bjorn Larsen (who entered the school at six, in 1920) liked to reminisce about the prevailing practice in his day: The new recruits were plunked down in the daily class given for students up to 16 and expected to follow, as best they could, complex, rigorous exercises that remain a challenge even to professionals. At that time, the training for company members as well as students consisted solely of the six set Bournonville Classes--one for each working day of the week--designed to preserve the technique the great ballet master had evolved from the basis of his own French schooling and fragments of his choreography.

One might assume that the secret of the Danish school lay in a particularly ingenious or efficacious training system. Yet, with certain exceptions, the program now being followed is significantly different from the various methods used in past generations. The late Niels Bjorn Larsen (who entered the school at six, in 1920) liked to reminisce about the prevailing practice in his day: The new recruits were plunked down in the daily class given for students up to 16 and expected to follow, as best they could, complex, rigorous exercises that remain a challenge even to professionals. At that time, the training for company members as well as students consisted solely of the six set Bournonville Classes--one for each working day of the week--designed to preserve the technique the great ballet master had evolved from the basis of his own French schooling and fragments of his choreography.

Needless to say, the Danes have adopted more modern methods, but since these have been subject to continual change, the success of the school can't be attributed to an exemplary syllabus. It must reside in elements that lie deeper.

The Bournonville legacy is clearly of major significance. Once the set classes were abandoned as the gospel of the training system, they were used only intermittently. However, the material they contain has been continuously cannibalized for classes by faculty members who have danced the ballets throughout their performing lives and draw upon it both instinctively and with a conscious appreciation of its instructional worth. "If you can dance Bournonville, you can dance anything," they like to say.

Another contributing factor to the success of the school is its location. In the corridors of the Royal Theatre, where they receive both their dance and academic schooling, the ballet pupils constantly encounter the personnel of the three companies performing there in tandem: ballet, opera, and drama. The youngsters themselves are frequently used in the productions, gaining stage experience even before their age registers in double digits, and they attend dress rehearsals as a matter of course. Along with the three R's, they drink in the three arts. This opportunity for intimate contact with a world they hope to join as professionals enriches their education in ways that can't be measured, but everyone is justly worried about its impending loss. The Royal Theatre's new opera house, scheduled to open in another part of town in 2005, threatens to break up the family.

Even less tangible, but still an element highly pertinent to the Danes' formation of dancers is the Danish character. The culture prioritizes warmth, camaraderie, and sensitivity not

merely to other people's feelings but also to the prevailing mood of the moment. The first question a Dane will ask you about a critical encounter is "What was the atmosphere?" Such matters are as consequential in dancing as a crackerjack technique.

Still nothing--not even the up-to-date methods of luring talent into the profession like sound outreach programs and jaunty flyers directed to the boys that ask "Can you lift a girl over your head?"--quite explains the phenomenon of the steady stream of admirable male dancers coming from the Danish school. So, being in Copenhagen, I went to have a look for myself, starting with the group called Team 2.

"Chest high!" begins the stream of directives, friendly but firm, to this little co-ed bevy of second graders. "Stomach in!" "Knees straight!" "Feet pointed!" Each injunction is a key to the kingdom of classical dancing, delivered bright with that promise. "Remember your arms!" "Remember your eyes!" Demonstrating this last, the instructor looks out and up--to a distant sight in an imaginary landscape. Every good dancer keeps an eye on this intangible place.

As is the custom in such institutions, the teachers in the RDB school are former company dancers, of major or minor rank, who have the gift of passing on their craft (perhaps even glimpses of their art) to youngsters, the youngest of whom are just learning to read, the eldest being in the throes of full-blown adolescence. The former soubrette who teaches this class of seven- and eight-year-olds achieves the perfect mix of mentor and mom.

Her pupils, veterans of a year's training, already seem different from ordinary kids. Distinguishing marks? Their well proportioned, flexible bodies and their highly developed rhythmic sense. Their capacity for intent concentration on physical minutiae, if still discontinuous, sets them off from pedestrian children too. Not more than five minutes into the class, though, they reveal the essential quality that separates them from the kid in the street: the ardent desire, the obsession even, directed toward an impalpable vision--something they saw once, fleetingly, or perhaps only dreamed.

At the start of the class, they stand at the barre like tiny military recruits, obedient and evenly spaced, their feet parallel. Then, at a word from the teacher, the small pairs of feet flick into turned-out first position (heels touching, toes of the left and right feet pointing in polar-opposite directions). Dance aficionados know the move from the opening of Balanchine's Serenade. It's the switch from the ordinary to the extraordinary, from life to art.

Today, as they did yesterday and will do again tomorrow, anchored to the barre or rooted to one spot in the center of the high-ceilinged studio, these children go about the chore of mastering ballet's basic positions and steps. It's a difficult, dry business that seems to have little to do with dancing, but it is indisputably the core of a classical dancer's training. Courtesy a new theory about encouraging beginners to persist in the process, the youngest RDB pupils are given little reprieves in which, embedding a given exercise in a looser dance phrase, they're allowed to move more freely through the room instead of waiting for the last segment of the class to release them into space.

Danish ballet's teaching style emphasizes a warm understanding between instructor and student. The younger the RDB school's pupils are, the more they are cosseted in this way. Often, the instructor stands as close to her pupil as would a Siamese twin to her other half, arm slung over the child's shoulder, transmitting shape and rhythm body to body. A child who hasn't quite seized the mechanics of a traveling phrase will be accompanied across the floor by his teacher, who dances full out by his side.

Danish ballet's teaching style emphasizes a warm understanding between instructor and student. The younger the RDB school's pupils are, the more they are cosseted in this way. Often, the instructor stands as close to her pupil as would a Siamese twin to her other half, arm slung over the child's shoulder, transmitting shape and rhythm body to body. A child who hasn't quite seized the mechanics of a traveling phrase will be accompanied across the floor by his teacher, who dances full out by his side.

Neophytes though they are, the children are considered artists of the Theatre. Their teacher reminds them constantly of the future they're aspiring to. Decorum is expected in the classroom as it would be in rehearsal or in the wings during a performance. Standards of comportment are related directly to the fact that an audience will be watching them. Accordingly, yawning and fidgeting are nipped in the bud: "How would it look if you did that on stage?" Aptly, today's class ends with the children's dance from the festive Act III of Napoli (the Bournonville ballet known as the RDB's calling card), in which the little ones, skipping in boy-girl pairs, trace a winding path through the crowd of their elders, as if binding up the generations. Despite a few inevitable missteps and lapses of coordination, the children move with engaging vivacity, swept up in danseglæde, a favorite term in the Bournonville universe--the joy of dancing.

"Use the floor!" the instructor calls over the pianist's upbeat accompaniment. "Use the music!" In two years time, the same pupils will be doing this dance on stage.

Fast forward now to Team 4, ten- to twelve-year-olds in their fourth year of training. These veterans maintain a rigorous schedule. Six days a week, at 8:30 a.m., they begin their hour-and-a-half ballet class. Quick shower, swift change of clothes, and it's off to academic education, which continues until early- to mid-afternoon on weekdays. The "reading school," as it's called, keeps the ballet children at public school level or better, thanks to its small classes (five or six pupils to a grade), which allow much individual attention. The students' rehearsals for their roles in Royal Theatre productions come out of the academic hours, but the kids make up the missed work. Even when a child has been onstage in the evening, he or she is back at the barre early the next morning, looking alert.

Once they turn 12, the boys in this division and higher meet for a  weekly gymnastics class--to build upper-body strength for lifting those girls over their heads and for, as an instructor put it, "joy and playfulness." Team 4 boys also have an extra, guys-only, ballet class once every two weeks (the alternate weeks being devoted to a similar one for the girls). This year's Team 4 boys' class, eight strong, is evidently geared to producing thinking dancers. It opens with an extended discussion of proper placement--before a single plié or tendu is attempted. After barre work and stretches, the boys cluster in a collegial circle around their teacher to discuss matters pertinent to their trade, as if they'd already served a decade in the corps de ballet. The center work of adagio, jumps, and pirouettes that follows is examined and executed inch by inch. At one point each boy in turn is required to perform a particular combination of steps by himself, closely watched by his comrades and teacher, and then to say what his mistakes or difficulties were. Throughout the session, the boys are urged to think about what they're doing and to articulate what it requires. In contrast to the monkey-see, monkey-do method that has prevailed traditionally, they are learning to take responsibility for their own dancing.

weekly gymnastics class--to build upper-body strength for lifting those girls over their heads and for, as an instructor put it, "joy and playfulness." Team 4 boys also have an extra, guys-only, ballet class once every two weeks (the alternate weeks being devoted to a similar one for the girls). This year's Team 4 boys' class, eight strong, is evidently geared to producing thinking dancers. It opens with an extended discussion of proper placement--before a single plié or tendu is attempted. After barre work and stretches, the boys cluster in a collegial circle around their teacher to discuss matters pertinent to their trade, as if they'd already served a decade in the corps de ballet. The center work of adagio, jumps, and pirouettes that follows is examined and executed inch by inch. At one point each boy in turn is required to perform a particular combination of steps by himself, closely watched by his comrades and teacher, and then to say what his mistakes or difficulties were. Throughout the session, the boys are urged to think about what they're doing and to articulate what it requires. In contrast to the monkey-see, monkey-do method that has prevailed traditionally, they are learning to take responsibility for their own dancing.

The approach might seem over-analytic, but it doesn't seem to quash the boys' innate physical fervor. Their teacher dissects a traveling phrase that climaxes the class to make certain each key position is correctly placed. Then, after several painstaking repetitions, she declares, "All the positions are right. Now you must just giv løs! (let 'er rip). And, legs shooting out to devour the space, leading arm flung high, charging recklessly along the diagonal as if walls would fall before them, they do.

The system doesn't seem to squelch their individuality either. In under an hour, four of them have made themselves unforgettable to me. Mads is the smallest one, with feet to die for and a face that is utterly appealing. He's a creature of the stage, fully aware of his charisma; class, for him, is performance. Though he still has only tentative control over his body, he seems to live to move. He may well be the most promising talent of them all. Frederik is the phlegmatic one. He looks like a suavely handsome banker, all gravitas. He works ably and calmly, as if resigned to his fate. Oliver of the mercurial charm knows he's someone worth watching and keeps glancing at the visitor to make certain he has her attention. While Mads instinctively plays to the house, Oliver is playing to you. Another boy whose name I didn't catch--was it Andreas?--introduces a welcome air of ordinariness into this artistic hothouse. Dark haired and olive skinned, with a scruffy look about him, he seems--despite his effort and ability--to be an ordinary kid who wandered in from the soccer field. His type is significant in our composite portrait of the Danish male dancer. He is the regular guy.

The day I see the co-ed Team 4 class, it's augmented by pupils from the Holstebro feeder school. One of the visiting boys immediately eclipses Mads, Frederik, Oliver, and (if this is his name) Andreas, though he's not their equal in accomplishment. He stands out simply as a danseur noble in the making. He has the tall, slim body, wide shoulders, and narrow waist of a fledgling prince. The poise of his head on his long neck is perfect. His quixotic face, framed in close-clipped auburn hair, might belong to a Tivoli Harlequin. His placement is still tentative; students in the early stages of their training lack the strength to maintain consistently ballet's alert stance, with the legs turned out like a fencer's. But this boy, operating with instinctive harmony and grace, makes the artificial posture, the classically sculpted positions, and the codified manner of moving look as if they were almost natural to the human body. Once the lesson progresses to big traveling steps, he displays a strong sense of rhythm, as do many of his comrades; this young fellow, though, seems to posses the more subtle gift of musicality.

The boy catches my eye immediately and holds it throughout the class, but I have no idea at this point that he might be genetically predestined for a dancing life. After class, I ask a staff member his name, just to complete my notes. "Luke," comes the answer. "Luke what?" I persist. "Luke Schaufuss," says my reluctant informant, perhaps an adherent of jantelov, the unwritten Danish law that holds that no single person should be allowed to be better than other folks. Luke, it turns out, is the son of Peter Schaufuss (himself the offspring of two noteworthy RDB dancers), in his performing days a virtuoso of international repute, one-time artistic director of the Royal Danish Ballet, now head of his own ballet company, based in Holstebro. If that weren't enough, Luke's mom, Zara Deakin, is a dancer, too. All in the family, I say to myself, but I think no more about it until I see the apprentice class.

Male students in the Danish school are referred to as "boys" until  they reach the age of 16. From the day they become apprentices, they're called "men," which indicates the gravity of their situation. The next two years (three if their development's sluggish) will constitute the most intensive period of their training. Having completed their academic schooling, they now frequently take their morning dance class with the company in addition to understudying the repertory and performing in entry-level roles. They take other classes with their female counterparts--the girls transformed into women--and have a couple of concentrated sessions a week just for themselves.

they reach the age of 16. From the day they become apprentices, they're called "men," which indicates the gravity of their situation. The next two years (three if their development's sluggish) will constitute the most intensive period of their training. Having completed their academic schooling, they now frequently take their morning dance class with the company in addition to understudying the repertory and performing in entry-level roles. They take other classes with their female counterparts--the girls transformed into women--and have a couple of concentrated sessions a week just for themselves.

The current crew of male apprentices, four in number, is coached by Niels Balle, a dancer known for his meticulous execution. He gives an exacting barre and remains equally scrupulous in the last third of the class, when the young men hurtle their bodies through space in feats that look near-suicidal. Just as they're about to pitch themselves into one of these thrilling ventures, Balle drawls, teasingly, but still expecting an answer, "And what should we remember?" Curbing their animal enthusiasm, his protégés cite the details that will keep the shape of their steps clear in the air and permit them to land with accuracy. Only then does Balle clear them for take-off. At one point, while they're aloft, Balle hushes the accompanist's full-blast support so the young athletes will hear, upon descent, if their footfalls are too loud.

These late adolescents, in whom the RDB is investing so much effort and hope, have gotten a good part of their growth now, but their bodies--in terms of posture, musculature, and control--are still under development. Their faces are typical adolescent masks of sullen passion. Their footwork at the barre--intricate as befits Bournonville's progeny--is unexpectedly light. By contrast, their legs unfolding in arabesque indicate huge commanding power. In the center, their jumps are buoyant in the air, cushioned in their descent; this is a Danish trademark.

Three in this group are commendably able artisans. They may yet develop artistry; the Danish men mature slowly. The fourth, Sebastian, already promises something else entirely. The youngest of them, and still slight, he has an elfin face; he looks like Ib Andersen in his youth and has the same poetic air. His big eyes are expressive, and he knows how to use them. His dancing is everywhere fluid, harmoniously coordinated, and infused with the luminous quality that, for lack of a more concrete word, we call soul. It's this--not the incredible feet and similar lucky assets, though they deserve admiration--that make him look like a born dancer and an incipient artist. Today he's wearing a dark gray t-shirt that darkens further in the course of the class as his sweat soaks it. On the back of the shirt, hitting its wearer just between the shoulder blades, like the target for an arrow shot to pierce the heart, is a tiny gold symbol. It's the royal insignia--a crown.

Sebastian uses his mother's surname. His mother is Eva Kloborg, a prominent RDB dancer and a teacher for both the company and its school. His father is Frank Andersen, who capped his stage career by becoming the present artistic director of the company.

So what's going on here? Am I any closer to understanding the circumstances that have favored the making of Denmark's marvelous male dancers? I've had a grand time observing; it's so much more vivid, complex, and revelatory than toying with theories. But what's the answer? Yes, genes do play a part in spawning talent, as many artistic dynasties testify. Bournonville's father, Antoine, headed the Royal Danish Ballet before August took over, eclipsing him. Peter Martins's uncle Leif Ørnberg and Peter Schaufuss's dad, Frank Schaufuss, held the same position after substantial careers on stage. Still I suspect that August Bournonville, an artistic father to succeeding generations of Danish dancers, is most responsible for their achievement. One can only hope that, despite contemporary pressures to modernize everything in sight, the Royal Danish Ballet will continue to keep this firmly in mind.

So what's going on here? Am I any closer to understanding the circumstances that have favored the making of Denmark's marvelous male dancers? I've had a grand time observing; it's so much more vivid, complex, and revelatory than toying with theories. But what's the answer? Yes, genes do play a part in spawning talent, as many artistic dynasties testify. Bournonville's father, Antoine, headed the Royal Danish Ballet before August took over, eclipsing him. Peter Martins's uncle Leif Ørnberg and Peter Schaufuss's dad, Frank Schaufuss, held the same position after substantial careers on stage. Still I suspect that August Bournonville, an artistic father to succeeding generations of Danish dancers, is most responsible for their achievement. One can only hope that, despite contemporary pressures to modernize everything in sight, the Royal Danish Ballet will continue to keep this firmly in mind.

Photo credit: Martin Mydtskov Rønne

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

Scotch Symphony and Donizetti Variations are thought of as Balanchine’s Bournonville-influenced ballets, the first because its situation borrows from the Danish master’s Romantic-era La Sylphide, the latter because its buoyant step combinations with their petite batterie recall Bournonville technique, which derives from French sources. (Balanchine operated most often in the Russian vein, from which he developed a unique American style.)

The 1952 Scotch Symphony, which has just entered the Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration repertory, capitalizes on Highland local color—the valiant kilted men; the unobtainable female spirit haunting the foggy landscape; the portents of doom. With a modicum of effort you can match the figures in Balanchine’s semi-abstract gloss to those of Bournonville’s Sylphide, though you can never make the whole business come out quite even.

The 1952 Scotch Symphony, which has just entered the Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration repertory, capitalizes on Highland local color—the valiant kilted men; the unobtainable female spirit haunting the foggy landscape; the portents of doom. With a modicum of effort you can match the figures in Balanchine’s semi-abstract gloss to those of Bournonville’s Sylphide, though you can never make the whole business come out quite even.

Each ballet has a hero who’s tempted by a sylphide--an ideal woman evoked, no doubt, by his imagination. Balanchine doesn’t bother to suggest reasons for his hero’s desire; his hero is only a cipher, a foil for the object of desire. Bournonville, on the other hand, suggests rich layers of motivation. Essentially, his James is a poet, aspiring to a joy found only in dreams and visions, fatally dissatisfied with the ordinary, which includes an appropriate fiancée.

Balanchine’s stalwarts in kilts, who form phalanxes to separate the Sylph from her suitor, match the lusty bagpipe-playing, reel-dancing fellows who, with their consorts, represent for Bournonville the community and its guarantee of life’s bourgeois blessings. Scotch Symphony’s Highland lass, traditionally a small, sturdily built woman with fleet feet and a bounding jump, who vanishes from the proceedings after her dazzling solo work, can be considered the equivalent of La Sylphide’s Effie, the really nice down-to-earth girl with whom a more sensible James would settle contentedly and raise a family.

Balanchine provides no equivalent of Madge, the witch who’s the lynchpin of Bournonville’s vivid narrative. Balanchine needs no witch because he needs no fatal curse. (He saves fatal curses for ballets like Divertimento from “Le Baiser de la Fée,” in which doom is not personified, but immanent in the very air his unfortunate lovers breathe.) In Scotch Symphony all’s well that ends well, and the male clan—paired with sweethearts whose airy costumes suggest they may themselves be tamed sylphs—obligingly forms an architectural frame for the wedding picture. Balanchine’s happy boy-gets-(no longer impalpable) girl ending—to a tale he has only implied—contrasts drastically with Bournonville’s tragic resolution. This is particularly interesting since Balanchine had a marked appetite for tragedy, Russian style, while all of Bournonville’s other extant ballets steadfastly take joy as their goal and realize it.

La Sylphide is top-drawer Bournonville and has earned a place in the repertory of ballet companies worldwide. Scotch Symphony claims to be nothing more than a pleasant diversion, but it, too, has endured. Why? First, its setting is recognizable, and attractive in its romance-of-legendary-Scotland way (think Sir Walter Scott). This ingratiates it with the part of the audience that may find ballets like Concerto Barocco and Agon repressively severe, complex, or unfathomable. Balanchine never forgot his obligation to entertain. Then it is—what Balanchine choreography is not?—deeply musical. And, while it may not pierce the mind or heart, it offers appealing images.

Some of these images borrow from the Scottish military tattoo and Highland dancing, with a group of equals arranged in grid formation, facing the audience straight on with fresh-faced frankness, torsos quiet, feet deftly drumming the floor. Others come from nineteenth-century Romantic ballet’s obsession with the ineffable and its prototypical heroine, a chaste temptress whose seductive wiles center on a tantalizing elusiveness: Come hither, but don’t touch me.

The current production delivers many of the images, but, as has become NYCB custom, without rubato and without their essential perfume. The corps de ballet is neat and lively, practicing exactitude adorned, in the women’s case, with empty smiles. As the tomboyish virtuosa, Carrie Lee Riggins is technically amazing. Period. Nilas Martins is embarrassingly miscast as the hero in terms of physique, presence, and sheer dance capability. Kyra Nichols, whose career is enjoying a luminous twilight, is surprisingly disappointing as the Sylphide. No longer wholly equal to the demands of the choreography, she’s chosen to rely on a style that’s too Taglioni-ish—etiolated to the point of spookiness. As a pair, Martins and Nichols are absurdly ill-matched. Anyone could have predicted that; what could management be thinking?

I had been looking forward to my favorite Scotch Symphony moment. Two of the kilts lift the Sylphide high—she seems to be standing on air—and toss her, still vertical, into her ardent suitor’s arms. “She sails forward as if the air were her natural home,” Walter Terry wrote in 1957, “and [her partner] catches her high on his chest as if she were without weight.” I recall the exquisitely gentle Diana Adams in that moment. For two unforgettable seconds, she seemed to be not falling but floating—softly, lazily, serenely, swept crosswise by an idle breeze. It didn’t happen last night. They didn’t even attempt it. I wonder if whoever is setting the ballet even knows that moment existed. Or cares.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Kyra Nichols, Nilas Martins, and ensemble in George Balanchine's Scotch Symphony

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

The trap in talking about Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream—with which the New York City Ballet has just opened the winter repertory season of its Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration—is comparing it to Frederick Ashton’s The Dream. (Balanchine’s take on Shakespeare’s play and Mendelssohn’s music was created in 1962; Ashton’s, in 1964.) The discussion quickly becomes a contest of merits—and Ashton usually wins. His one-act ballet is not merely more succinct and cohesive, it also harbors more emotional resonance. But what if we considered the delights of the Balanchine—and they are many—on their own?

The atmosphere Balanchine invokes—of a fairyland that can absorb human incursions and is itself fully capable of folly—is big on charm. A happy choice for matinees or early summer evenings, the ballet embodies a sweetness and light that never cloys. Think, for instance, of the child corps de ballet of insects and butterflies skimming through two acts more lithely and lightly than any of their seniors could manage, then reappearing at the close, airily wafting their arms, the tiny lights they’ve hastily fastened to their hands between one entrée and the next glimmering like stars against the soft descending darkness.

The atmosphere Balanchine invokes—of a fairyland that can absorb human incursions and is itself fully capable of folly—is big on charm. A happy choice for matinees or early summer evenings, the ballet embodies a sweetness and light that never cloys. Think, for instance, of the child corps de ballet of insects and butterflies skimming through two acts more lithely and lightly than any of their seniors could manage, then reappearing at the close, airily wafting their arms, the tiny lights they’ve hastily fastened to their hands between one entrée and the next glimmering like stars against the soft descending darkness.

For pure dance highlights there is, first, the brilliant scherzo in which Oberon becomes a perpetuum mobile of fiendishly swift jumps and leaps. And then, as the climax of the second act’s celebration of connubial bliss, there’s the pas de deux performed by dancers who arrive anonymously, having had no role in the ballet’s narrative. They’ve come to make manifest what all couples aspire to, whether they be of the fairy kind, of the earthly aristocracy, or just plain bumbling folks committed to their passion. Traditionally performed by mature stars, this sublime duet seems to be proof that ideal love—the perfect accord of two quite different beings—exists, if only on an abstract plane.

Balanchine didn’t hold much with mime, yet when it was required he could produce it effectively. The trick, as he demonstrates in Midsummer, lies in the timing. Titania and Oberon’s argument over the ownership of the changeling child and the courting mishaps of the quartet of human lovers owe their vividness and vitality to the fact that Balanchine, consummate musician that he was, knew how clocks tick and hearts beat.

As for the delineation of characters, the exquisite Titania’s willfulness owes much to Shakespeare, but the endearing pathos of Bottom turned ass, more tempted by a handful of succulent grass than by the joys of romantic or erotic love, is Balanchine’s creation. Balanchine was, of course, inspired to a degree by the dancers on whom he chose to create the ballet’s roles. The feral quality that Arthur Mitchell brought to Puck, for instance, preventing the virtuoso feats of the role from looking coarse, has never been replicated. In any story ballet, much of the characters’ character is dependent on the dancer playing the role at a given moment, and that’s one aspect of Midsummer that’s at stake today.

The opening night performance was exuberant (almost to a fault) and at least intermittently magical. Three roles were magnificently done. The veteran Peter Boal created an Oberon who was a golden king—in deportment as well as costume. Though the role is usually assigned to an airy high-flyer, Boal—all grave nobility in his mime, all clear, weighty shape in his dancing—was a ruler of fairyland whose prime quality was gravitas. As always, Boal projected the seriousness, purity, and modesty that seem to be part of his own character.

Dancing Puck, another veteran, Albert Evans, recaptured some of the creaturely quality that dominated Arthur Mitchell’s portrayal, fashioning it to fit his own style. The result was an engaging mix of nature spirit and show biz.

In the love-in-the-abstract duet, Miranda Weese, masterfully partnered by Jock Soto, offered an immaculate example of classical dancing at its most objective—cool, calm, flawlessly beautiful. Weese, now at the peak of her career, though sadly underused, might prove to be an apt successor to Kyra Nichols as the company’s custodian of pure style.

Darci Kistler, once a perfect Titania, served as a rueful reminder that no magic lasts. Her former dance power now depleted, she was forced to overemphasize the steps and phrases she can still bring off and to rely a little too heavily on her native sweetness. Her efforts are valiant, and not without effect. When they flagged, I comforted myself with memories.

In smaller (though not lesser) roles there were two stand-outs. James Fayette devised a Bottom who was equally unique, funny, and lovable as an unlettered human laborer given to amateur theatricals and a docile if occasionally stubborn ass bewildered by his transformation. In a higher social niche, Rachel Rutherford made a delicious Hermia, the girl who is too much loved.

Where would critics be without complaint? The fault I found in this Midsummer was that it was too punched up. The mime, brisk and sharp-edged, was several degrees too vehement and indeed the whole production suffered from a frenetic air. The School of American Ballet pupils in the children’s roles looked as if they were trying to jump out of their skin. Perhaps everyone will relax a little in subsequent performances and allow the choreography a more generous breathing space in which to exercise its spell.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnick: Darci Kistler and Peter Boal in George Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Kirov Ballet of the Maryinsky Theatre / Kennedy Center Opera House, Washington DC / December 30, 2003 – January 4, 2004

Daria Pavlenko, dancing Odette-Odile, was far and away the best thing about the three performances I saw (all three casts) of the Swan Lake the Kirov Ballet brought to Kennedy Center. She has, beside formidable technique, the magisterial authority of a ballerina. This is rooted in the ability to draw the audience into an imaginary universe of which she is the center.

Daria Pavlenko, dancing Odette-Odile, was far and away the best thing about the three performances I saw (all three casts) of the Swan Lake the Kirov Ballet brought to Kennedy Center. She has, beside formidable technique, the magisterial authority of a ballerina. This is rooted in the ability to draw the audience into an imaginary universe of which she is the center.

Pavlenko is gifted for both lyrical and dramatic dancing—a perfect endowment for the dual personality of her Lake assignment. Her Odette displays an infallible harmony of line coupled with a flowing quality that prevents the sculpted shapes from being reduced to a series of handsome poses. The Russians call this the cantilena—singing—style, and Pavlenko lends it an added touch of grace with her delicate and eloquent use of her hands.

There’s more to this Odette, though, than ravishing dancing. Using—what, exactly? belief? fantasy? her big, flashing, dark eyes?—Pavlenko creates a potent expressive figure, an innocent young woman struck by tragedy. She calls to mind literature’s legendary victim-heroines as well as girls whose terrible fate you read about in the newspapers, the promise of their youth blighted by a random act of destiny.

Every move Pavlenko makes relates to the condition of Odette. When she chalks up even more experience in the role, she should be able to add a narrative element to her portrayal, so that Odette evolves from the opening of the Act II duet with Siegfried to its close, having experienced hope and the beginning of love. At the performance I saw, the audience didn’t scream and yell at the conclusion of the pas de deux the way it had for the Jester’s blitzkrieg antics in Act I, but when Pavlenko came back onstage for her solo, it got very, very quiet, signaling respect and anticipation.

With Odile, Pavlenko is working hard to create a believable figure that will be a counterfoil to Odette. The persona isn’t fully realized yet, but I’m eager to watch its further evolution every step of the way. With an artist of Pavlenko’s caliber, process is as fascinating as product. Here, too, she does much with her eyes, fixing them on Siegfried to see if her seduction’s working; glancing repeatedly at von Rothbart, father and coach, to receive further instructions; peering out at the audience, as if it were another group of party-guest/witnesses, seated along the imaginary fourth wall of the stage. Combined, that ravening gaze of her eyes and her minxish smile are positively diabolical, and the business of engaging the spectator in her agenda is deeply disconcerting, making you feel, minutes before poor Siegfried does, what it’s like to be the victim of black magic. She’s strong and sharp in the virtuoso dancing, and if she’s a little troubled by those damned 32 fouettées, she faces up to them with appetite as well as courage.

The fire of Pavlenko’s Odile enriches the persona of Odette that she returns to in the elegiac Act IV, increasing its pathos. When Siegfried first appears after betraying her, the look she gives him mirrors his remorse—focuses it, perhaps even dictates it. Reproach is irrelevant. She makes their ensuing duet an act of mourning for thwarted love, trust, and hope. Her dancing in this act grows increasingly fluid, as if her corporeal self were melting, fading, disintegrating. In Act II Pavlenko’s Odette is a girl with a problem. By Act IV, she has become the problem itself, a poetic abstraction, worthy of the word sublime.

Pavlenko’s resourcefulness is so rich, it even carries her through the Sergeyev production’s close, where she has to cope with the ludicrous happy ending the Russians imposed on Swan Lake during the Soviet period, to make the ballet politically correct. Not even she can make this turn of events cohere with the tragedy called for by the preceding choreography, to say nothing of Tchaikovsky’s score. She simply plays her sudden good fortune as a storybook miracle, her face radiant with surprise and delight, like a child’s on her birthday, receiving a gift that has been ardently desired yet too extravagant to be hoped for.

The second best thing in the Lake performances was the work of the female corps de ballet. Perhaps to offset the ballet’s companion piece in the engagement, a controversial newfangled Nutcracker, the Kirov brought its Konstantin Sergeyev staging of Swan Lake, a tradition-respecting production from 1950. Here, in its extended passages in Acts II and IV—sequences in which the ensemble is the whole show—and in its creating a frame that gently echoes the movement and mood of the soloists, this wonderful corps de ballet registered as an entity greater than almost any of the company’s individual stars.

It goes without saying that much of the effect is due to Lev Ivanov, the original choreographer of the ballet’s lyrical “white” acts. Yet choreography really exists only in performance, and the Kirov’s anonymous swans are admirable for their discipline, their musical response, and their submission to the demands of creating communal poetry. After their long “solo” in Act II, they fall still, profiled in diagonal lines, backs curved forward in sorrow, heads averted. As their action subsides, they seem to will their own transformation into a pictorial state. Entering, Siegfried gazes at them and he’s looking at a landscape of beauty and grief that expresses—before he has any specific knowledge of these things—Odette’s story and his own fate.

Granted, today’s Kirov corps is not the ensemble it once was, with every head inclined just so, every wrist angled exactly, every leg raised in arabesque to some preordained height, the uncanny unison work not mechanical but buoyed by the music. Still, the current group resembles the corps de ballet of the old days in kind if not degree, and it is a fine sight to behold.

The rest of the dancing was dispiriting. In contrast to the elements I’ve praised, large stretches of the performances were flaccid. This suggests the absence of artistic staff assigned to watch with an eye to keeping up standards of physical energy and emotional engagement, a carelessness that is as inexplicable as it is inexcusable. What’s more, the company simply does not have—or did not bring on this tour—enough world-class dancers to cover the principal soloist roles adequately. One evening it introduced its boy wonder, the 21-year-old Leonid Sarafanov, who has an undeniably light and airy jump, but is in no way qualified to play princely heroes like Siegfried. In appearance Sarafanov would make a perfect Peter Pan or, better yet, Tintin. He was nearly devoured by his ballerina who, beside his diminutive figure, blank face, and cautious, unprepossessing presence, looked like the kind of woman mothers warn their innocent sons to steer clear of.

The most heartening dancing after Pavlenko’s came from two women in the pas de trois, which revs up the dance-thrill factor in Act I. Strong, precise, and ebullient, these young women made a perfectly matched pair, like sisters in a fairy tale—one sweet and fair-haired, the other a scintillating brunette, both with flashing smiles. Both are built like soubrettes (compact and delectable). Both have perfected the Kirov jeté, which the choreography makes much off, leaping high and wide, the front leg thrusting upward as well as forward as it cleaves the air, the back leg curving slightly as an added fillip. And both have clearly been schooled to understand that blurring or smudging a step counts as a capital crime. The public was not allowed to know the names of these proficient charmers, the casting of the pas de trois being omitted from the house program. For the record, they are Irina Golub and Tatyana Tkachenko, and they deserve all the notice they can get.

Photo of Daria Pavlenko © 1998 Marc Haegeman

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Beginning January 6, I’m planning to go to the New York City Ballet a lot.

I haven’t gone to the NYCB a lot in years. My attendance started falling off after Balanchine’s death in 1983, because, without the man there—as creator, coach, teacher, and all ‘round inspirational force—performances of his ballets deteriorated, slowly but inexorably.

No room here for the placing of blame. After all, it’s a birthday party! The New York City Ballet, naturally the main custodian of Balanchine’s work, is celebrating the 100th anniversary of the choreographer’s birth with, this season, seven weeks of repertory performances.

Just look at the schedule: On paper, at any rate, it makes me weep with pleasure. Well, almost. Six of the season’s eight weeks will blessedly be dominated by all-Balanchine programs. The only non-Balanchine works on the mixed bills are Fokine’s Chopiniana (aka Les Sylphides) and Bournonville’s Flower Festival at Genzano pas de deux, both demonstrably germane to Balanchine’s history.

Just look at the schedule: On paper, at any rate, it makes me weep with pleasure. Well, almost. Six of the season’s eight weeks will blessedly be dominated by all-Balanchine programs. The only non-Balanchine works on the mixed bills are Fokine’s Chopiniana (aka Les Sylphides) and Bournonville’s Flower Festival at Genzano pas de deux, both demonstrably germane to Balanchine’s history.

During this period, the sole departure from the canon will be seven performances of Broadway choreographer Susan Stroman’s new program-length Double Feature, an oblique homage to Balanchine’s work for the commercial stage and no doubt a necessary provision for an audience ravenous for novelty, as audiences invariably are. Balanchine’s own work for Broadway will be represented by Slaughter on Tenth Avenue, from On Your Toes.

The two final weeks of the season will be given over to The Sleeping Beauty, its landmark Petipa choreography reconfigured by Peter Martins, with Balanchine’s hand present only in the Garland Dance. This ensemble waltz, in which little- and big-girl students intertwine with adult couples who are full-fledged professionals, was Balanchine’s nostalgic tribute to the legendary Maryinsky school and company in which he was bred. Decades later, he contemplated the possibility of producing the whole ballet for the NYCB, but that project, sadly, never came into being. Yet even in Martins’s version—which assumes that today’s viewers are too impatient to tolerate, let alone appreciate, the expansive leisure of the nineteenth-century classics—Beauty serves to remind us of the ways in which Balanchine absorbed and extended Petipa’s aesthetic principles.

Martins’s full-length Swan Lake will also be given several showings, though Balanchine devotees might well prefer Mr. B’s one-act version—an inventive “essence of Lake”—that has all but disappeared from the active rep. The short version has become a curiosity; the long version insures good box office.

The season’s schedule makes a related concession to the preferences of today’s paying public by giving over a disproportionate number of slots to Balanchine’s program-length works, Coppélia, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Jewels, the last really a trio of ballets tenuously connected by an idea and a set, two of them perfectly capable of standing alone. Balanchine’s most substantial achievement lies in his shorter works, most of them abstract or, like Serenade, hauntingly semi-abstract. Still, audience surveys—and consumer preference controls what happens on the concert stage almost as firmly as it rules the world of commerce—have proved without a doubt that today one long ballet with a story sells best. Balanchine himself might have agreed that this is an oddly retrogressive state of affairs.

But just imagine: There will be programs like Apollo, Serenade, and Prodigal Son (January 22) and Donizetti Variations, Concerto Barocco, and Scotch Symphony (February 7, matinée). Not a dud, not a Martins or a Wheeldon or an also-ran among them. (Jerome Robbins will get the inclusion due him in the spring season.) This is surely an occasion both for reveling in the genius of Balanchine and seeing, without the usual distractions, how the first post-Balanchine generation has nurtured its formidable legacy.

So here’s my plan: I go. I look. I make notes. (I always make absurdly copious notes. Note taking at a dance performance is not merely a journalist’s tool for supporting inadequate memory. It’s a device that lets her believe for a foolish moment that she’s capturing the ephemeral.) Next morning latest I post my informal report on what I believe I saw and what I made of it. The subject and the set-up lends itself to blogging, don’t you think?

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture