Seeing Things: December 2003 Archives

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater / City Center, NYC / December 3, 2003 – January 4, 2004

Time was, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, 45 years old this season, specialized in dances with humanitarian themes. Created largely by Ailey and a handful of other black choreographers working in the same vein, this repertory took as its subject the fight of a stalwart, resilient people, fueled by hope—a near-miraculous optimism, given their circumstances—to overcome injustice, oppression, and their corroding, often lethal, results. (In this, it echoed the liberal/socialist mindset that pervaded mid-twentieth century modern dance without regard to ethnicity.)

Corollary to this aim ran the impulse to proclaim the multi-faceted beauty of black culture by depicting its people in moments of joy, play, and celebration. Ailey’s signature piece, Revelations, choreographed in 1960, says it all. As does Donald McKayle’s deeply affecting Rainbow Round My Shoulder (1959, handsomely revived this season), which contrasts the physically and spiritually brutal life of men on a chain gang with their dreams of womankind as the source of ideal love. Succor disguised as sassy authority (mother), delicious lust (sweetheart), tenderness and constancy (wife)—all, poignantly evoked, are lost to them, just as they are lost to the women they’ve left behind, grieving.

Corollary to this aim ran the impulse to proclaim the multi-faceted beauty of black culture by depicting its people in moments of joy, play, and celebration. Ailey’s signature piece, Revelations, choreographed in 1960, says it all. As does Donald McKayle’s deeply affecting Rainbow Round My Shoulder (1959, handsomely revived this season), which contrasts the physically and spiritually brutal life of men on a chain gang with their dreams of womankind as the source of ideal love. Succor disguised as sassy authority (mother), delicious lust (sweetheart), tenderness and constancy (wife)—all, poignantly evoked, are lost to them, just as they are lost to the women they’ve left behind, grieving.

Not surprisingly, such works, which now represent the “traditional” element in the Ailey rep, contain a big ecstatic element—intensely felt if improbable visions of better times, a better world, a better fate, to be brought about by the sufferers’ faith in a power that lay beyond objective reality. Salvation, the message went, surely lay in the next life, if not in this one.

At the time of the company’s founding, part of its mission was to showcase black dancers and black choreographers, who were denied equal opportunity on the dance scene, and to speak to a black audience eager to see material that reflected its concerns and affirmed its sense of self. (It was assumed, rightly, that the non-black part of the audience—and the dance world at large—could only benefit from this strategy.)

The Ailey, now internationally popular, has seen no reason to change its position. Most of the troupe’s phenomenal dancers would identify themselves as black, as would many of its choreographers. The rising generation of American dance makers is particularly rich in black practitioners, and some of the emerging talents—Ronald K. Brown in the forefront—show tremendous promise.

Postmodernism has, of course, made its impression on the Ailey, and many of the latter-day dances added to the repertory have been abstract, shorn of specific characters, situations, and narratives. Oddly enough, though, the old themes keep surfacing in the newer works—as subtexts. The recent pieces reflect the difficult tenor of the times (though no longer in specific terms of the black experience), where alienation in a cruelly uncaring world prevails, turning the citizenry into soulless beings, even when they’re ostensibly having fun. And many of the newer dances are built on the strategy of repetition intensifying to a climax that is not merely physical release but an epiphany experienced by the soul.

Mindful of the eternal yen for novelty—on the part of the dancers as well as the audience—the Ailey unveiled four new works this season, by both black and white choreographers, and all four fall into this framework.

Jennifer Muller’s Footprints, the best of the lot, depicts a clan of pilgrims seeking a promised land or state of being indicated only by—what else?—light. They falter and fall by the wayside, then pick themselves up and persevere; they succumb to personal “issues” and internal dissention only to re-identify, through a tame but ostensibly transformative ritual, with a communal order and purpose proposed as the ultimate good. Freshly unified, the tribe proceeds on its seemingly eternal quest, though the lovely troubled maiden at the center of the action (Asha Thomas, a star in the making), hesitates and looks back, an icon of ambivalence. The piece is constructed with a scrupulous intelligence that, alas, prohibits maverick inspiration. Its originality is confined to the brilliant costumes by Karen Small, who should open a boutique immediately. Needless to say, Footprints is gorgeously danced, demonstrating that choreographic invention and depth are not as essential to pleasure as they are to art.

Jennifer Muller’s Footprints, the best of the lot, depicts a clan of pilgrims seeking a promised land or state of being indicated only by—what else?—light. They falter and fall by the wayside, then pick themselves up and persevere; they succumb to personal “issues” and internal dissention only to re-identify, through a tame but ostensibly transformative ritual, with a communal order and purpose proposed as the ultimate good. Freshly unified, the tribe proceeds on its seemingly eternal quest, though the lovely troubled maiden at the center of the action (Asha Thomas, a star in the making), hesitates and looks back, an icon of ambivalence. The piece is constructed with a scrupulous intelligence that, alas, prohibits maverick inspiration. Its originality is confined to the brilliant costumes by Karen Small, who should open a boutique immediately. Needless to say, Footprints is gorgeously danced, demonstrating that choreographic invention and depth are not as essential to pleasure as they are to art.

The score commissioned from John Mackey for Robert Battle’s Juba is highly percussive and so is the choreography, based on the premise—investigated variously by the whirling dervishes, Mary Wigman, Laura Dean, and Lucinda Childs—that incessant repetition ferries you to a higher plane of consciousness (or whatever). Battle, who has a flair for the effective gimmick, gives us a quartet sealed into a tight matrix of togetherness, beating feet into floor and fists into thighs. The never-let-up thudding flicks the audience’s response switch to “On,” encouraging the view that the anonymous, relentlessly animated figures are not trapped, but actually enjoying themselves.

With Bounty Verses—set to music ripped from strange bedfellows like Bach, Steve Reich, and Kurt Cobain—Dwight Rhoden has created his usual knock-‘em-dead showpiece. Its frenetic disco atmosphere reflects the hectic nature of urban lives lived, as they are today, at unremitting high intensity, with its consequent mindlessness. In the world Rhoden represents, nothing—not a passage of dancing, let alone an affair of the heart—can be sustained. The piece is guaranteed to raise your stress level but, mercifully, it’s an example of time out of mind tonight, forgotten tomorrow.

Alonzo King’s unfathomable Heart Song mates a vocabulary co-opted from classical ballet with songs of Arabia and chichi stylistic devices typical of dance in the 1920s. Is King borrowing ironically from Europe’s patronizing view of black dancers—as creatures fascinating in their otherness—prevalent at that time? Heart Song is too unfocused to tell, but I’ve filed it in the exoticism category for the moment.

I doubt that any of these works will last long in the repertory; there’s no reason why they should. Next year the company might do well to relinquish one of its New Ballet slots to a resurrection from its Warehouse of Golden Oldies. Perhaps, since Donald McKayle restaged his Rainbow so vividly, a revival of his District Storyville is now in order, not merely for its historical value, not just because it would make a telling show, but also because it has the Ailey’s interests at heart.

Photo credits:

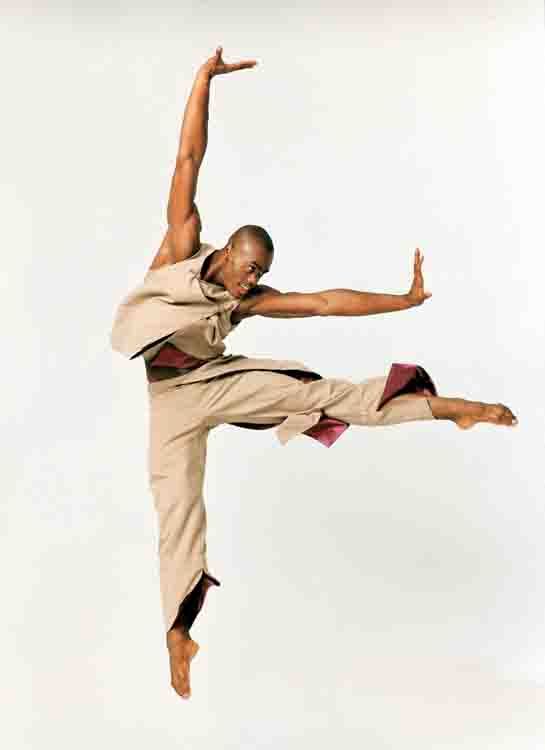

1. Andrew Eccles: Glenn A. Sims and Matthew Rushing in Donald McKayle’s Rainbow Round My Shoulder

2. Andrew Eccles: Jamar Roberts in Jennifer Muller’s Footprints

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Shocking! The Art and Fashion of Elsa Schiaparelli:

Philadelphia Museum of Art / September 28, 2003 – January 4, 2004

Musée de la Mode et du Textile, Paris / March 17 – August 29, 2004

Even before I went to see Shocking! The Art and Fashion of Elsa Schiaparelli, the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s lavish retrospective (the first of its kind), I was cheered by reading about the designer’s life. In these exhausted times, accounts of the personality and adventures of a woman so creative, daring, and defiant are definitely good news.

Born in Rome in 1890, into an intellectual and artistic family with aristocratic connections, Schiaparelli was a non-conformist from childhood. At the age of six, it appears, she ran away from home, to be found by her family three days later marching down the street at the head of a parade. Her attitudes as an adolescent made her incompatible with parochial schools of both Catholic and Protestant persuasions. At twenty-one, she published a book of erotic poetry—to her parents’ surprise and dismay. (Consistently, they later condemned her opening her couture atelier as going into trade).

If Schiaparelli wasn’t genetically programmed to be a provocateur, her childhood circumstances would have made her one. The mirror no doubt reflected the truth of her mother’s repeated assertion that her older sister, Beatrice, was the beauty; she, Elsa, the homely one. Her response was prophetically inventive and poetic: She planted flower seeds in her nose, ears, mouth, and throat, hoping to become the ground from which a garden of beauty bloomed. Gradually, through more sophisticated means of self-expression, she found ways of both securing her share of attention and love from the world and forging a singular identity. Beauty, evolving from the futile desire to possess it personally into the creation of it, remained at the heart of what she did.

How did Schiaparelli look? Do looks matter? Of course they do. This is fashion we’re talking about. Images are everything. Billy Boy, to whom Schiaparelli was a heroine, tells us she was built like a Tanagra statue—in other words, small, narrow, fine-boned. Physically (and to some degree temperamentally) she might be compared to another indomitable creative creature, Martha Graham, who was her contemporary.

Obsessive, as many youngsters are, about bodily perfection, the young Elsa felt her face was marred by a group of small moles on one cheek. An uncle, who happened to be a celebrated astronomer, pointed out that the configuration resembled the position of the stars in the Big Dipper and that this was a lucky sign. At the time, Elsa was unconsoled by the benevolent observation, but the adult Schiaparelli took the constellation as her personal emblem and commissioned a brooch that traced its design in diamonds.

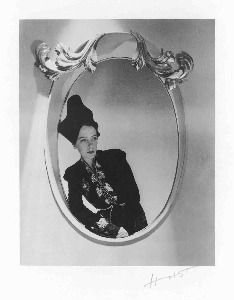

If Schiaparelli was not a beauty, neither was she a belle-laide, as is sometimes claimed. Women in that category have a confidence in their self-presentation that she lacked. Portrait photographs of her reveal an undercurrent of uneasiness or uncertainty. The famous one by Horst that plays with the ambiguity of mirror reflections presents her as a melancholy introvert.

If Schiaparelli was not a beauty, neither was she a belle-laide, as is sometimes claimed. Women in that category have a confidence in their self-presentation that she lacked. Portrait photographs of her reveal an undercurrent of uneasiness or uncertainty. The famous one by Horst that plays with the ambiguity of mirror reflections presents her as a melancholy introvert.

An early, hasty marriage to a humbug theosophist (was this move another of Schiaparelli’s rebellious whims?) failed shortly after she gave birth to their daughter. Even this sad development had its gaudy aspect: Her husband left her for Isadora Duncan. Typically, Schiaparelli rebounded from adversity. Marriage had taken her to New York, where she began to find herself and her life’s work. She then relocated to Paris (a city she had recognized as “hers” when she first laid eyes on it briefly, a decade before) and settled in. A series of fortunate acquaintanceships (with the likes of Gabrielle Picabia, wife of the Dadaist painter, and the doyen of haute couture, Paul Poiret), a few pick-up jobs that allowed her to feel her way into fashion’s domain, and her career was launched.

Schiaparelli first made her mark with a sweater, a cunningly knit trompe

l’oeil take on a boxy black “canvas” feminized by a pale bowknot—a kind of modernist jabot—with smartly matching cuffs. Catching American eyes, it became an instant hit. On the strength of this, without formal training or practical experience in dressmaking, Schiaparelli opened an atelier, albeit one confined to a garret, in 1927. She began in sportswear and, though by 1930 she was moving on to daytime and evening clothes for town wear, her interest in practical clothes never flagged. She put the tennis champion Lily d’Alvarez in a split skirt that scandalized the lawn tennis crowd at Wimbledon in 1931. In 1936, a time when a female piloting a plane was called an aviatrix (on a par with a poetess), she designed a useful and handsome working outfit for Amy Johnson, who was making a daring solo flight. For herself she created an easy-care, mix-and-match wardrobe for her extensive travels.

As she extended her scope to the more glamorous aspects of clothing design, Schiaparelli expanded her business, moving to gradually more ample and luxurious premises. The public seized upon her originality, and Schiaparelli, in return, thrived on the celebrity that swiftly came her way.

First in New York and then in Paris, Schiaparelli made it her business to associate with the artists and intellectuals who contributed so much to the ferment of those cosmopolitan capitals. She identified them as soul mates. (Though her youthful education offered no training in couturier skills, she had studied painting and sculpture.) Her aesthetic was influenced early on by the Dadaists—among them Marcel Duchamp, master of piercing, cryptic ironies—then, profoundly, by the Surrealists, who were building dream worlds of improbable but psychologically acute landscapes and events, almost self-consciously aware of the shock value of their imaginings. Among the Surrealists who affected Schiaparelli’s sensibility were Salvador Dalí, Jean Cocteau, Christian Bérard, René Magritte, Alberto Giacometti, Léonor Fini, and Meret Oppenheim (she of the fur cup). With some of them she worked hand in hand.

Dalí was incontestably Schiaparelli’s primary Surrealist influence (and collaborator). Two dresses that resulted from their association have become fashion icons. The Lobster Dress is devoid of tailoring interest; it’s all about image and implication. Observers have been quick to construe phallic meaning from the giant crustacean that descends from the area of the mons veneris. I wonder if there isn’t a reference to menstrual blood or a horrific birthing here as well. Whatever the case, the vermilion lobster makes a startling contrast with the ingénue simplicity of the white gown that serves as its canvas; only a wide lobster-colored belt mediates between the two. Drifting hemward, a few parsley garnishes suggest that the whole conceit is a joke.

Dalí was incontestably Schiaparelli’s primary Surrealist influence (and collaborator). Two dresses that resulted from their association have become fashion icons. The Lobster Dress is devoid of tailoring interest; it’s all about image and implication. Observers have been quick to construe phallic meaning from the giant crustacean that descends from the area of the mons veneris. I wonder if there isn’t a reference to menstrual blood or a horrific birthing here as well. Whatever the case, the vermilion lobster makes a startling contrast with the ingénue simplicity of the white gown that serves as its canvas; only a wide lobster-colored belt mediates between the two. Drifting hemward, a few parsley garnishes suggest that the whole conceit is a joke.

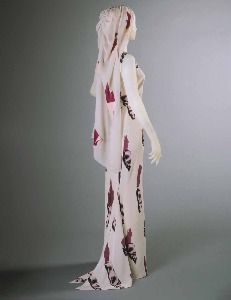

Taking its inspiration from a Dalí painting, the Tear Dress, in form an innocuously graceful gown, packs its whammy in the content of its print. The narrow, floor-length dress is cut from white silk crepe decorated (this is perhaps not quite the word we want) with images of grayed-pink skin ripped away to reveal streaks of crimson that can only be raw, blood-suffused flesh. (Imagine a torn hangnail monstrously enlarged to conjure up the wounds of war.) A similar print is used on gossamer fabric for a generous hood that lengthens into a thigh-grazing shawl; here the torn strips are rendered in three dimensions.

Schiaparelli also linked up with the sweet ironies of Cocteau’s poetic vision, translating a pair of his continuous-line drawings into embroidered images on apparel. On the back of an evening coat, the outline of two facing profiles (both female, from the look of their glowing cherry lips) creates the negative shape of an urn. A close-packed bouquet of plump appliquéd pink roses springs from the top of the vessel as if to declare “Love, you have won!” On the front of a linen jacket, a woman’s profile segues into a shoulder, arm, and hand, while her hair--long waves of pink-gold bugle beads and clearly the stuff of legends—streams down the length of one sleeve.

Schiaparelli also linked up with the sweet ironies of Cocteau’s poetic vision, translating a pair of his continuous-line drawings into embroidered images on apparel. On the back of an evening coat, the outline of two facing profiles (both female, from the look of their glowing cherry lips) creates the negative shape of an urn. A close-packed bouquet of plump appliquéd pink roses springs from the top of the vessel as if to declare “Love, you have won!” On the front of a linen jacket, a woman’s profile segues into a shoulder, arm, and hand, while her hair--long waves of pink-gold bugle beads and clearly the stuff of legends—streams down the length of one sleeve.

From Surrealism, too, comes the element in Schiaparelli’s aesthetic that associates the eerie, the sinister, the macabre, and the morbid with  glamour, creating a kind of chic noir. A pair of low boots sprouting monkey fur—long, black, shiny, and coarse—from ankle to floor are as amusing as they are threatening, something Charles Addams’s Morticia might be sporting if only we could see her feet. But a black wool jersey top that covers the chest and back with the same fur induces the lurid fantasy that the wearer has sprouted the pelt herself. Even today, when we’ve seen just about everything, the piece alarms.

glamour, creating a kind of chic noir. A pair of low boots sprouting monkey fur—long, black, shiny, and coarse—from ankle to floor are as amusing as they are threatening, something Charles Addams’s Morticia might be sporting if only we could see her feet. But a black wool jersey top that covers the chest and back with the same fur induces the lurid fantasy that the wearer has sprouted the pelt herself. Even today, when we’ve seen just about everything, the piece alarms.

Scholars of fashion hold that the influence of the Surrealists accounts for the butterfly motif in Schiaparelli’s work, the insect being a symbol of metamorphosis, a subject dear to those artists. Surely it has as much to do with Schiap’s personal desire to transform herself into something lovelier than the reality she saw in the mirror. A flock of butterflies cavorts, giddy and unfettered, on a simple waltz-length pink gauze frock that is all girlish euphoria. In a second dress, acquired wordly wisdom corrects such ingenuous prettiness. Here, the butterflies’ brilliant hues have intensified; their dark outlines have grown heavier. The narrow silhouette of this garment has already curtailed their flying space; a black net overdress wholly extinguishes their freedom. The overdress balloons at the sleeves with the ease and volume of a butterfly net trawling the air, but it’s implacably cinched in at the waist by a black belt. A jet butterfly ornaments the belt, a signal that loveliness—winged and evanescent—has been pinned to the specimen board.

Though the iconoclasm of the Surrealists exhilarated Schiaparelli, the ensembles she created for urban leisure-class women also reflected the suave, untroubled glamour prevalent in the late thirties, her heyday as a designer and a halcyon period before the Second World War. She excelled at dual-purpose evening costumes with this agreeable scenario (we know it today from vintage movies): Cover a slinky, ankle-brushing dress with a snug, elaborately embroidered jacket for a dinner date. Then peel off the jacket to reveal inches of bare back, and you’re dressed for the dancing that follows. Many of the jackets involved were boleros, short- or long-sleeved. Gradually the concept evolved—losing some of its charm, I think, even flirting with vulgarity—to include longer jackets, coats, and capes encrusted with heavy, bold embroidery, paillettes, self-important buttons, metal ornaments, and artificial gems, as if the woman wearing the garment were a four-star general of status and chic.

Nearly all the creations displayed in the Shocking! exhibition conform to one genre or another that Schiaparelli, operating like most couturiers, chose to investigate in depth for a time, playing with an idea until she’d exhausted it (or it, her) or fashion’s next season loomed, calling for novelty. A few pieces, however, seem to be sui generis, among them my personal favorite in the show, a relatively unobtrusive coat for a winter’s eve.

Yes, in the course of her career, Schiaparelli explored the idea of cloaking thoroughly, her creations ranging from cool weather regalia to immense lightweight scarves, cut from fabric that was the same as or closely related to the airy material of a summer dress. These could either sit on the shoulders and swathe the torso or hood the head and stream toward the floor, proposing the partially veiled body as a chamber of secrets. But the item I would steal from the show, given half the chance (few can go to an exhibition of fashion without playing this game), is singular—and remarkable both in its avoiding visual or social confrontation and in its tremendous evocative power.

A ground-brushing evening coat in claret silk velvet, it’s trimmed in sable. The fur is applied in sparing amounts, not just at the neck but at the shoulders, where it takes the form of burgeoning wings. (On this evidence alone, any little girl worth her salt—and a few little boys, too—would recognize the garment as a costume fitting a fairy-tale creature.) Set at the small of the back, there’s a bustle unlike any bustle you’ve ever seen. It’s not the conventional rounded protuberance, exaggerating the firm, plump flesh of the buttocks, but rather a flat rump pack. From the thin ledge it provides, the coat’s fabric falls in columnar ripples, like a theater curtain, all the way to the floor, promising, as theater curtains do, to reveal the imagination’s wonders. The coat is otherwise plainly cut, modestly narrow in its proportions, almost demure, enveloping the figure without calling attention to it. Its subtly proffered extravagances are all the more spellbinding for that. The garment exemplifies magic that creeps up on you without speaking its name, taking you unawares.

Often, Schiaparelli centered a season’s collection on a theme. The most memorable of these—Circus, Pagan, Zodiac, Commedia dell’arte, and Music—reflected either a personal penchant or her instinct for the Zeitgeist, often both. The themed collection (and the presentation of it as a performance art event) are typical of innovative Schiaparelli practices that have become so commonplace, today’s designers often have no idea of their debt to her.

In the Zodiac collection, Schiaparelli let her imagination run riot, associating (or, more accurately, free-associating) her fascination with the workings of the galaxy, her playful superstitious faith in lucky charms, and her flair for magical thinking. Here, too, through references to Louis XIV (the “Sun King”) and the extravagant palace he built at Versailles, she indulged herself in an orgy of magnificent excess, producing garments that emblazon (indeed, almost extinguish) the torso with designs heavy on gilt and mirrors. These pieces flout notions of good taste, just as Versailles flagrantly enlarges upon its inspiration, Nicholas Fouquet’s exquisite Vaux le Vicomte.

A quieter piece, a dinner-suit jacket that takes the heavens as its province, serves as a reproof to the flamboyant entries. Its black fabric becomes a night sky illuminated by gleaming and twinkling elements. The signs of the zodiac, planets, constellations, a crescent moon, and shooting stars—all are embroidered or appliquéd in just proportion to the garment and to the human torso destined to serve as its armature. The beading is so very fine here, it creates the illusion of stardust. An example of beauty and luxury working hand in hand with tact, rooted in a universe the child Elsa once examined through her astronomer uncle’s telescope, it ranks among the mature Schiaparelli’s finest achievements

Schiaparelli had a taste for striking, off-beat fabrics. She particularly relished a tactile element emphatic enough to be visually perceived, as is evident in her use of “tree-bark” cloth, with its rough surface of irregular swirling ridges. Her penchant for artifice accounts for her experiments with a blatantly artificial “glass” material, which looked like cellophane and proved equally fragile. She used prints that brimmed with gaiety and wit. In one, rakishly sketched carousel animals, a rabbit on a bicycle among them, cavort on a ground of brilliant blue or deep rose. In another, swallows fly through sprigs of spring blossoms bearing envelopes closed with sealing wax that must be billets-doux. For the opening of the Place Vendôme salon that confirmed the status she’d achieved, she had fabric printed with a collage of her press clippings. What’s more, she liked to displace textiles from their prescribed assignments—rough-textured stuff was no longer confined to daytime and ordinary occasions, delicate tissues to evening and the extraordinary. In the secret life of the inanimate, tweeds and silks no doubt recognized her as their liberator.

Equal in importance to the fabric, in the case of many Schiaparelli creations, was the elaborate embroidery that adorned it. Indeed, the contribution of the ingeniously skilled House of Lesage rose at times to the status of a collaboration of equals. A bolero dinner jacket with a circus motif is all embroidery, beading, and appliqué work; not a millimeter of the anchoring fabric shows. Sumptuously embroidered elephants, costumed and standing on drums, at diaphragm level are echoed above by a crisscrossing parade of minuscule elephant paillettes linked trunk to tail. The air-inhabiting pachyderms form a network of high wires for men daringly launched from a flying trapeze that lies outside the jacket’s purview. The ostensibly neutral background of this high-spirited scene is thick with stitchery too; heavy sand-colored thread is worked in an irregular, curving abstract pattern that recalls the depiction of waves in Eastern art. The Lesage ornamentation doesn’t operate against the organic feel of clothing—the fanciful scene depicted has something of a tattoo’s malleability—but it also stakes a claim to the condition of art for art’s sake.

Growing up, Schiaparelli had studied painting, and her eye for color was keen and subtle. She possessed a natural instinct for assembling both contrasting colors and related shades of them into ménages à trois or quatre that seemed to be made in heaven. Ironically, she’s best known for a pair of very simple color choices: black and white, alone or coupled, varied by surprising textures, and the lush, audacious Shocking Pink, guaranteed to sear your eyeballs and make you happy. The vibrant hue is a reproof to the pale rose assigned to female infants (or perhaps a hopeful promise about the little girls’ future); Schiap didn’t invent it, but took it as her trademark. She gave the name Shocking to the perfume the House of Schiaparelli bottled in a clear glass sculpture of a seriously curvy lady’s torso and hips (it was based on Mae West’s hourglass figure). Just as enterprisingly, she called her memoir Shocking Life. An antique Chinese robe in Shocking Pink served as her shroud.

Accessories were central, not peripheral, to Schiaparelli’s work. (It must be admitted that the clothes themselves tend toward the condition of accessory in that they often make more of a decorative impression than the structural—architectural—one that garments built on rigorous tailoring achieve.) With her daring, witty accessories, Schiaparelli makes a persuasive argument for the idea that frivolity is important, one of the key enhancers of human existence.

Accessories were central, not peripheral, to Schiaparelli’s work. (It must be admitted that the clothes themselves tend toward the condition of accessory in that they often make more of a decorative impression than the structural—architectural—one that garments built on rigorous tailoring achieve.) With her daring, witty accessories, Schiaparelli makes a persuasive argument for the idea that frivolity is important, one of the key enhancers of human existence.

Schiaparelli had studied sculpture in her youth and later referred wistfully to an unfulfilled desire for a career in this art. Her gift for three-dimensional shape surfaces most tellingly in her hats. To my mind, some of them are more innovative in form than the clothes she produced. Sketches for the group of hats that includes the notorious upside down shoe reveal a consanguinity with the biomorphic forms of Jean Arp. While Schiap headgear—crowning women with a windmill, a caged canary, a lamb chop—calls attention to itself by means of amusing eccentricity, even its most outré examples can harbor a deeper dimension. That black pump arcing its shapely heel into the air came in a version that colored the heel crimson—a reference, perhaps, to a fashion affected by Louis XIV that became a privilege confined to the French aristocracy.

Extending her design province into the realm of costume jewelry, Schiaparelli fashioned pieces that were always striking and, when allied to the Surrealist aesthetic, often intriguingly bizarre. Most memorable among these efforts is a necklace in which a small infestation of metallic, jewel-toned, winged and creeping insects is mounted on a see-through strip that suggests flexible glass bent to encircle the wearer’s neck. The beauty and the intrigue of the piece lie in its mating a frisson of horror with an homage to nature—and in the ingenuousness of its construction. A child might have made it. Indeed, a child could replicate it today, for a couple of bucks spent on New York’s Canal Street for a strip of clear plastic and a set of Made in China painted tin bugs. Beside it, the jewelry fashioned for Schiaparelli’s collections by bigwigs like Jean Schlumberger, using far most costly materials, seems a little tame today.

Schiaparelli’s insouciant use of novelty buttons places them in a category lying somewhere between accessory and jewelry. Some of the buttons referred to an earthly natural world (leaves and acorns; crayfish, lobsters, snails, and swans), some to a celestial one (sunbursts, astrological forms), some to the theater (Harlequin masks, trapeze artists, clowns). They ran a madcap gamut from cupids to cartridge casings.

The designer also enjoyed playing with the buttons’ size and placement, using outsize buttons, asymmetrically placed buttons, buttons abandoning their fastening function to morph into brooches or migrate to hats. She experimented with other devices, too, for making ends meet, such as the newly invented zipper—the lightning fastener, as it was called. Revealing rather than concealing it, as conventional tailoring did, she lent the zip the audacity of a bolt from the blue.

And let’s not forget perfume. After her runaway success with Shocking, Schiaparelli created several other fragrances, which were always artfully packaged as well as artfully advertised. Snuff, her first scent for men, came in an amber-tinted glass pipe derived from René Magritte’s road-sign clear painting of a pipe above an inscription insisting “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (the point being that the image is not a pipe but, obviously, a picture). The name of the painting is La trahison des images (The Treachery of Images). Magritte’s position is more dogmatic than Schiap’s; her work joyfully confirms fashion’s canon: image alone is sufficient delight.

Schiaparelli’s headiest period of achievement and fame was the latter half of 1930s, which made her the rival of the earlier established Gabrielle Chanel. The two acknowledged each other’s existence with scathing comments. Chanel on Schiaparelli: “That Italian artist who’s making clothes.” Schiaparelli on Chanel: “That dreary little bourgeoise.” Together the two were the lynchpins of couture between the world wars, “Coco” Chanel defining a modern version of classical elegance, Schiap subverting the code of sublimity in favor of more maverick, and inevitably more ephemeral, pleasures.

Not unexpectedly, Schiaparelli dressed celebrities, and their appearance in her ensembles in their spotlighted circles naturally served as a walking advertisement that, in turn, extended the notoriety of their maker. Wallis Simpson (notably on the eve of her becoming the Duchess of Windsor), Daisy Fellows, Millicent Rogers, and Lady Mendl numbered among the couturière’s socialite patrons. Theater personalities wearing Schiap’s creations on or off stage included Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Katharine Hepburn, Joan Crawford, Gloria Swanson, Tallulah Bankhead, and Arletty. Schiaparelli was not for the timorous. In her “Twelve Commandments for Women,” whose oracular force is sadly uneven, she did declare usefully that women (1) do not know themselves, (2) should try to do so, and (3) should dare to be different.

During World War II, Schiaparelli took shelter in the States, where she refused to design, manifesting her solidarity with her French colleagues, stymied in their work by the Nazis. When the war ended in 1945, she reestablished herself in her Paris atelier, but the era in which her singular vision meshed with the prevailing Zeitgeist had ended. In 1954 she closed up shop and wrote her memoirs. She died in 1983, in her sleep—one hopes at the climax of an extravagant dream filled with the imaginative people, the animals and insects, and the astronomical elements that constituted her private pantheon, any member of the participating cast requiring or desiring clothes impudently and ravishingly attired.

During World War II, Schiaparelli took shelter in the States, where she refused to design, manifesting her solidarity with her French colleagues, stymied in their work by the Nazis. When the war ended in 1945, she reestablished herself in her Paris atelier, but the era in which her singular vision meshed with the prevailing Zeitgeist had ended. In 1954 she closed up shop and wrote her memoirs. She died in 1983, in her sleep—one hopes at the climax of an extravagant dream filled with the imaginative people, the animals and insects, and the astronomical elements that constituted her private pantheon, any member of the participating cast requiring or desiring clothes impudently and ravishingly attired.

Because history is effectively dead in the current climate of our culture, nothing counts much these days unless it can be shown to be happening now. So today’s observers like to claim for Schiaparelli a significant influence on subsequent generations of designers, most prominently Yves St. Laurent (who has articulated his debt to her in words as well as clothes) and the way-out guys of the minute, John Galliano and Jean Paul Gaultier. In truth, Schiaparelli’s power to inspire extends far beyond the realm of design. An hour’s immersion in the Shocking! retrospective (if you miss it in Philadelphia, you’ll just have to catch it in Paris) is likely to make even the most circumspect soul understand that rules may exist to be broken and that perhaps all the would-be iconoclast needs is sufficient—Schiaparelli-scale—panache.

NOTE: The Schiaparelli exhibition is complemented—expanded in scope and extended in duration, actually—by a book written by its curator, Dilys E. Blum. Shocking! The Art and Fashion of Elsa Schiaparelli (published by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press; $65) is exhaustive, well-written, full of ideas, and lavishly illustrated with color photographs to die for. It will find a suitable home both in libraries and on coffee tables. An earlier book—less ambitious, more to the popular taste—still worth reading is Palmer White’s Elsa Schiaparelli: Empress of Paris Fashion (Aurum Press, 1986; updated edition 1995).

Photos:

1. Horst P. Horst. Elsa Schiaparelli wearing an ensemble from her winter 1937-38 collection. Courtesy of the Staley-Wise Gallery, New York. © Condé Nast Publications Inc., New York

2. Elsa Schiaparelli. Hand-knit pullover sweater with bowknot, November 1927. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

3. Elsa Schiaparelli. Evening dress with lobster print (collaboration with Salvador Dalí), summer/fall 1937. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

4. Elsa Schiaparelli. Evening coat (collaboration with Jean Cocteau), fall 1937. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

5. Elsa Schiaparelli. Boots, summer 1938. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

6. Elsa Schiaparelli. Gloves, winter 1936-37. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

7. Elsa Schiaparelli. Evening dress and head scarf with tear design (collaboration with Salvador Dalí), summer 1938. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Dayton Contemporary Dance Company / BAM: Harvey Theater / December 9-13, 2003

Dayton Contemporary Dance Company (DCDC to its friends) has been celebrating its 35th birthday and the 100th anniversary of the Ohio-born Wright Brothers’ first successful launch into space with “The Flight Project.” Comprising five commissioned works (from Bill T. Jones, Bebe Miller, Dwight Rhoden, Doug Varone, and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar) plus a company premiere (by Warren Spears), it was delivered as a pair of programs at BAM’s Harvey Theater, the final stop on an extended tour.

Certainly the subject of the human body’s sloughing off earthly shackles to claim air as its element is apt for dance, given the art’s constant challenge to gravity’s pull and its ecstatic emotional dimension, often equated with soaring. But from the program I saw (Rhoden, Miller, Varone) and from program notes and interviews with the choreographers (those wily print devices that tell what a dance can’t say), it appeared that the dance makers had interpreted their subject so loosely as to make it well nigh invisible. The actual show looked to me like business as usual—extraordinary dancers in dances that are competent enough, but more the diversions of an evening than items headed for history, the combination arranged into the glossy packaging that ensures survival in our times.

Rhoden’s Sky Garden, set to a New Age score by Antonio Carlos Scott) and purportedly an homage to DCDC’s indomitable founder, the late Jeraldyne Blunden, serves only as a showcase for the company’s stunning dancers. The women, many of them compactly built with ample, gloriously muscled buttocks and thighs, epitomize the post-feminist ideal of powerful-and-sexy. They look as if their bodies have been honed by a combination of a gutsy modern dance technique (perhaps Martha Graham’s), classical ballet, and weight training—with an occasional jazz class thrown in to provide rhythmic sizzle. The gentlemen, in general, are considerably taller and slimmer than their ladies and—predictably for their more willowy build—more lyrical. Everyone is sensationally strong, swift, and fluid—capable, for instance, of shooting up into the air in extravagant postures without taxiing on the runway.

Neatly and logically arranged, infused with an energy that borders on the violent, the choreography for five couples (one of them “more equal than others”) is, like most of Rhoden’s efforts, all surface sensation, remarkably devoid of subtext. This, I think, is why you can’t get your attention to adhere to it for more than twenty seconds at a stretch: vivid as all get-out, it says absolutely nothing.

Aerodigm (with music from Giovanni Sollima, Jurgen Knieper, and Laurie Anderson) is typical of Bebe Miller’s work: thoughtful, touching, occasionally whimsical, deeply textured, a little muddled, luminous with a simplicity and an integrity that are regrettably rare today. Bette Kelley’s disarming costumes, a fanciful cross between pajamas and farm clothes in faded shades of blue, gray, and brown, reflect the down-home air of the choreography in which rural working folk are seen to have dreams, fears, and visions—perhaps even more resourceful ones than the world’s Haves. A fanciful introduction involving the juggling of three golden balls no larger than spaldeens is succeeded by a hoe-down section, a dark night of the soul section, and a sanguine conclusion that finishes with the plump, contagiously joy-filled girl who drew us into Miller’s imaginary world at the start sailing cross-stage on roller skates to assure us that all is well. Thanks to Miller’s gift for calibrating tone, none of this is corny. All it needs is an editor—or perhaps a gardener, to clear out the underbrush and let the trees stand tall.

Doug Varone boldly (recklessly, if you will) co-opted Stravinsky’s Firebird score for his contribution, The Beating of Wings, but apart from some references to the old Russian tale that the composer drew on and the ballets subsequently choreographed to the music (Fokine’s the first and finest among them), he essentially made a Varonesque work. In it, he explores, once again, the effect on an insular community of an outsider who differs so drastically in kind from the natives that the encounter is doomed to darkness and turbulence, even disaster.

Doug Varone boldly (recklessly, if you will) co-opted Stravinsky’s Firebird score for his contribution, The Beating of Wings, but apart from some references to the old Russian tale that the composer drew on and the ballets subsequently choreographed to the music (Fokine’s the first and finest among them), he essentially made a Varonesque work. In it, he explores, once again, the effect on an insular community of an outsider who differs so drastically in kind from the natives that the encounter is doomed to darkness and turbulence, even disaster.

Here the intruder (ferociously played by Sheri “Sparkle” Williams) is a tiny, tight-wound woman who yearns for flight but is curiously incapacitated. The community, led by two large men who act as her handlers, are a gentle, loving bunch, who first try hands-on physical rehab and large doses of sympathy. When it becomes clearer, through the woman’s wide-eyed fear and spastic trembling, that her problem is psychic, they assist her in meeting her doomed fate. (The rigging by which the dancer is hauled skyward in a flickering shaft of lurid light provides its own sense of fatal danger.)

The message of the piece seems to be that a close-knit group, whose bonding depends on a mutual definition of normalcy, can’t possibly absorb the aberrant exile because they can’t know her. She lies outside their limits; despite their good will and best efforts, all they can do is help her fulfill her destiny as victim or saint.

I like the obsessiveness with which Varone has returned to the outsider/insiders theme, once again giving it a new setting and angle of view. I like the understanding and respect he shows for the souls on both sides of the dilemma. And I admire his ability—inconsistent though it may be—to convey such a subject through dance. But we are at some distance here from Kitty Hawk.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Doug Varone’s The Beating of Wings

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary