Seeing Things: November 2003 Archives

New York City Ballet: The Nutcracker / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / November 28, 2003 – January 4, 2004

The Nutcracker

The Nutcracker

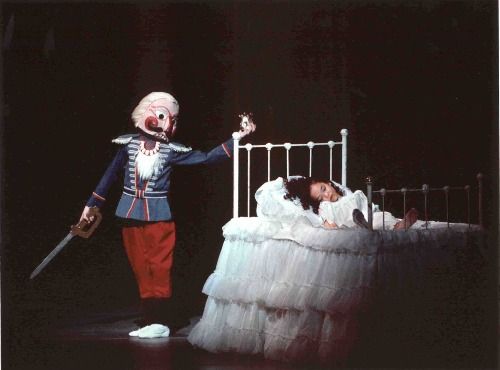

In this latter guise—conveyer of child to endless rehearsals—I, along with the other moms, dads, and nannies, occasionally got to watch a stage run-through. I remember in particular a dress rehearsal supervised by Mr. B himself. Decades later, it still provides me with a clue to the great man’s sensibility. On this occasion, matters had worked around to the point where Marie, the ballet’s juvenile heroine, terrified by the attack of the predatory mice, flees to a white-ruffled bed, stands on it for a moment, all innocence and vulnerability in her little white nightdress, then tumbles backward in a faint.

Her fall looked fine, albeit a little smudged, to me, but Balanchine wasn’t satisfied. He asked that she repeat it and was no happier with the result. He went up to her and, with typical gentle courtesy, worked directly with her—quietly and intimately, as if the two of them were alone on the stage—explaining and showing what he wanted. Then he stood back as she tried again. It was still not right in Balanchine’s eyes. Turning from her so that she didn’t see his little twitch of impatience and exasperation, he addressed the children’s ballet master and the other assistants in attendance: “Somebody teach her how to faint.”

How to bow, how to faint, how to waltz. Over years of mere glimpses of Balanchine at work and many an interview with his dancers, I came to understand that these skills were as important to the choreographer as a breathtaking mastery of the classical dance vocabulary he did so much to advance. I think it disturbed him at the core when dancers (even child dancers, because they represented his art’s future) couldn’t execute convincingly the moves that any citizen of civilization can perform almost instinctively. Balanchine, as his work reveals, gloried in the high artifice of ballet, but he never divorced his art from human nature.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: George Balanchine's Nutcracker

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / November 25, 2003

The George Balanchine Foundation: Videotaping of Violette Verdy coaching George Balanchine's Emeralds / Samuel B. and David Rose Building, Lincoln Center, NYC / October 27, 2003

Works & Process: Balanchine's Lost Choreography / Guggenheim Museum / November 16 & 17, 2003

January 22, 2004 marks the 100th anniversary of George Balanchine's birth. The celebratory "year" that is wrapped around this propitious date follows the art and social worlds' custom of beginning in the fall and extending through the following spring. It has been and will continue to be filled with activities centering on the man who shaped twentieth-century ballet according to his singular vision. No end of exhibitions, archival undertakings, film and video screenings, symposiums, and - most important - productions of the ballets worldwide are calling attention to Balanchine's genius. (A continually updated schedule of the happenings is available at http://www.balanchine.org/05/archive/2003cent3.html.) There will even be a George Balanchine postage stamp, Mr. B sharing an American Choreographers commemorative with Miss Graham, Miss De Mille, and Mr. Ailey. (Leave it to the U.S. Postal Service to indicate the marginality of dance in our culture by determining that none of its practitioners deserves solo homage!)

January 22, 2004 marks the 100th anniversary of George Balanchine's birth. The celebratory "year" that is wrapped around this propitious date follows the art and social worlds' custom of beginning in the fall and extending through the following spring. It has been and will continue to be filled with activities centering on the man who shaped twentieth-century ballet according to his singular vision. No end of exhibitions, archival undertakings, film and video screenings, symposiums, and - most important - productions of the ballets worldwide are calling attention to Balanchine's genius. (A continually updated schedule of the happenings is available at http://www.balanchine.org/05/archive/2003cent3.html.) There will even be a George Balanchine postage stamp, Mr. B sharing an American Choreographers commemorative with Miss Graham, Miss De Mille, and Mr. Ailey. (Leave it to the U.S. Postal Service to indicate the marginality of dance in our culture by determining that none of its practitioners deserves solo homage!)

Despite this all-over-the-map activity or, perhaps, stimulated by it, one still looks to the New York City Ballet, Balanchine's home base during the major part of his career, for the truest performances of his canon. In the course of its extended winter and spring seasons at the New York State Theater (aka the house built for Balanchine), amid a flurry of peripheral activities, the company promises to perform 54 of the choreographer's works, 42 of them created for the NYCB. "Balanchine 100: The Centennial Celebration," as the project is called, will be further extended by national and international engagements. (For details, go to http://www.nycballet.com/nycballet/homepage.asp and click on the "Balanchine 100" poster.) The incomparably rich repertory will be organized into easily identified categories: "Heritage" this winter, "Vision" in the spring, with subsets grouping the ballets according to the composers of their scores. While this corralling and labeling is no doubt necessary for marketing purposes, what ultimately matters is the quality of the productions themselves.

On November 25, the company offered a single night of repertory, preceding the endless weeks of "The Nutcracker" that help pay its bills. The event temptingly offered itself as a litmus test, indicating how the Balanchine legacy is faring in the place where its treatment counts most.

The program consisted of "Serenade," the first ballet Balanchine made in America and one of the most inventive, beautiful, and moving he ever made; "Bugaku," a top contender in the choreographer's "strange and marvelous" mode; and that icon of neoclassicism, "Symphony in C." The performance of this last ballet was the most commendable - for its rendering of crisp clean dazzle throughout the ranks. And overall the evening demonstrated that the New York City Ballet remains by far the most eminent custodian of Balanchine's work, a force schooled to dance with a precision and musicality that still look like news. Yet the very fact that this needs to be said indicates some flaws in the picture.

I believe that a good part of the problem is that no one is as deeply and unremittingly concerned as Balanchine once was with the nature of individual dancers' specific personas and gifts. He was acutely conscious of such matters when he created his ballets and when he recast them over the years as well. He developed his dancers not merely in the classroom but through the roles he gave them. Nowadays, casting often seems thoughtless. Kyra Nichols, Yvonne Bourree, and Sofiane Sylve, dancing the three leading women in "Serenade," made a disconcertingly odd trio; they hardly seemed to be in the same ballet. Bourree looks weak and ineffectual, while Sylve is robustly athletic but not yet able to give her physical force a dramatic dimension. Nichols, on the other hand, in the last stage of her performing career, technically muted though still gloriously pure, has become increasingly luminous emotionally. She alone seemed to know that something is going on in "Serenade" besides steps.

The casting of Darci Kistler in "Bugaku" was well-nigh disastrous. At this point in her dancing life, what with the erosions of injury and age, she's not equal to the technical demands of the piece. Even more significantly, the peculiar stylized Japanese-court eroticism of the piece is utterly uncongenial to her fresh-faced American girl style and temperament. Her formidable imagination carried her a long way, as usual, but not, I think, in the direction Balanchine was going here. But then the whole piece has been shorn of its original atmosphere, and without the sense of exotic ritual and mystery that once informed it, it seems, by turns, pointless and vulgar.

In all three ballets, actually, most of the principals' dancing looked badly in need of coaching, and the ballets themselves lacked a sense of vision behind them. It's the rare dancer who can figure things out entirely on his or her own. And choreography is not just an objective text of moves; it requires interpretation. This is where the custodians of history come in. Once a choreographer is no longer available to revivify his or her works, dancers who knew them best can help to recreate them and ensure their ongoing viability.

Since Balanchine's death in 1983, however, the NYCB, essentially under Peter Martins's direction, has been reluctant to let Balanchine's celebrated galaxy of ballerinas (and important male dancers as well) participate in coaching its productions of the ballets to whose creation or rich ongoing life they contributed so memorably. Artists of the caliber of Suzanne Farrell and Violette Verdy, who effectively do such work for other American companies (Farrell now has her own) - and abroad from Paris to St. Petersburg - are shut out at home, Balanchine's home.

The George Balanchine Foundation has instituted two archival video projects that demonstrate what can be accomplished when the past is retrieved and revered. Launched in 1994, the Interpreters Archive, according to its statement of purpose, "documents the coaching of Balanchine roles from those on whom the roles were created in order to preserve original choreographic intent." The recordings of Allegra Kent, the most haunting of Balanchine's ballerinas, coaching "Bugaku" and "La Sonnambula" alone prove the worth of close personal instruction from dancers set in motion by the choreographer himself.

I had the privilege recently of observing the day-long taping of Violette Verdy coaching dancers from the NYCB in the solo and pas de deux (assisted here by her partner, Conrad Ludlow) that she originated in the "Emeralds" section of "Jewels." As Verdy worked - with her usual brisk energy, seemingly concentrating on practicalities of steps and rhythms - she restored to the ballet the full force of its signature texture and perfume. At one point she attempted to elicit from the very young Carla Körbes, an exceedingly promising NYCB talent, the quality that she, Verdy, brought to the arm and hand gesture that is a key motif in the solo. Demonstrating as she spoke, Verdy suggested that she think of the hand as a long, lovely feather with which the girl caresses her cheek. Though Körbes has never even seen the ballet live, she's an apt vessel for received wisdom, and she got it in one. The phrase she had first reproduced mechanically - to perfection - was now transmuted into an emanation.

Edited, the videotapes in this project are made available to research libraries worldwide. In other words, they have arrived at, and will continue coming to, a source near (or accessible to) you. So you can see for yourself, without taking my fallible word for it, elements of Balanchine's vision no longer present in today's productions of a given ballet, qualities that, if attended to, could add significantly to the resonance of current stagings.

Another Balanchine Foundation enterprise, the Archive of Lost Choreography, according to the dry, modest reportage of the organization, "retrieves fragments of Balanchine works no longer performed." This too, is essentially a videotape project - material to be accessed at a library - but its latest incarnation was vividly supplemented with live public performance. In the estimable Works & Process series at the Guggenheim Museum, Maria Tallchief (foremost among Balanchine's early American muses) and Frederic Franklin (profoundly influenced by Balanchine at the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo) worked with young NYCB dancers on versions of "Le Baiser de la Fée" and "Mozartiana" that Balanchine later discarded in favor of his new conceptions of their respective Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky scores. Ironically, the old, recouped choreography offered the felicitous shock of the new, even to a veteran viewer like me. Imagine, here was the very thing we never expected to see again, a new Balanchine ballet (well, only a passage from one, but still . . .).

The evening was enhanced by film fragments of the material being rescued from oblivion, danced inimitably more than a half century ago by Tallchief, Franklin, and Alexandra Danilova. It was also punctuated by interview segments with the articulate senior artists on hand, conducted by the dance scholar (and former NYCB dancer) Nancy Reynolds, who masterminds both the projects discussed here. At one point Reynolds proposed, rhetorically, of the original "Baiser," "So it's a lost ballet," to which Tallchief snapped back, "Not while Freddie and I are around."

Franklin, sharp and spry as they come, active as a stager and coach in many venues, blessed with a sanguine personality that makes him the most accessible of instructors, also has a birthday coming up. He'll be 90 in June. What is the dance world waiting for? It is now twenty years since Balanchine's death. Let's assume that Balanchine's home team, for its own good or not so good reasons, chooses to forego the input of Balanchine's illustrious associates. Surely other companies can benefit from their counsel - indeed, from their very presence. What is now done to some extent on an ad hoc basis is crying out to be organized and subsidized. What more suitable birthday tribute to Balanchine could there be?

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: New York City Ballet bows to Balanchine, November 25, 2003

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Rosas (Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker) / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, NYC / November 12-17, 2003

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Rain, performed by her Belgium-based company, Rosas, draws upon defining devices of early postmodern dance—the inventions and innovations of the late 1960s and the 1970s—and gives them a sleek, forceful theatricality. Indeed, it makes them fit for an opera house—the venue, laden with tradition, on which postmodernism originally turned its back in contempt. Such a development is both ironic and inevitable—the mainstream is a magnet for the work of its rudest antagonists—and De Keersmaeker’s piece is very handsome indeed.

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Rain, performed by her Belgium-based company, Rosas, draws upon defining devices of early postmodern dance—the inventions and innovations of the late 1960s and the 1970s—and gives them a sleek, forceful theatricality. Indeed, it makes them fit for an opera house—the venue, laden with tradition, on which postmodernism originally turned its back in contempt. Such a development is both ironic and inevitable—the mainstream is a magnet for the work of its rudest antagonists—and De Keersmaeker’s piece is very handsome indeed.

The pictorial aspect alone is stunning. The setting, designed and lighted by Jan Versweyveld, is a circular amphitheater demarcated by a curtain of hanging cords. It might be a field of prowess or combat; a stage, like the Greeks’, for theatrical endeavor; or perhaps the planet Earth, surrounded by a nebulous cosmos. The lighting bathes the structure in a pale golden glow, a cross between the qualities of sun and moon. The scene darkens several times, in response to the course of events, but never looses its immanence.

The dancers’ simple, casual costumes—by the Belgian couturier Dries Van Noten—echo the neutral pallor at first. Unobtrusively, as the piece progresses and the energy of the dancing intensifies, their palette shifts to include livelier colors: bright raspberry, flame, and damped-down tangerine. It shifts again as the dance winds down, subtracting the brighter hues and substituting the sheen of ivory satin, the glitter of metallic thread, as if to indicate that the wearers have earned celestial status.

Seated in a ring behind the cord curtain, visible as through thin-bladed half-open window blinds, black-clad members of Ictus and Synergy Vocals perform Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians, a hypnotic score typical of those used by pioneer postmodern choreographers, once they capitulated to using music at all.

Rain opens with movement that looks very natural—well, choreography-style natural—emphasizing running and loosely flung limbs. It builds gradually but inexorably, adding to its modern-ballet base gymnastic feats and inflections from foreign climes—capoeira and the like—all relying on elastic joints and quick reflexes. Buoyed by the mesmerizing music, the action goes on for seventy minutes without a break, accreting into one of those feats of sheer endurance that audiences love to greet (and did on opening night at BAM) with standing ovations.

The piece begins with a longish stretch of ensemble work in which all of the figures have equal importance. Eventually the group of ten dancers (three men, seven women) breaks down into smaller units—septets, trios, duets, even brief solo turns—woven with masterly skill into the picture of the whole population. Midway, a long passage suggests the community’s selecting one of its young women for a rite-of-spring-style sacrifice. Instead of building to fever pitch, though, the idea is deliberately allowed to blur. The victim is excused and allowed rejoin the clan, another is chosen, and then the whole matter is dropped, almost absent-mindedly, the myth seemingly depleted of its significance, given the current climate of the imagination.

Another, more specifically erotic motif succeeds the sacrificial-virgin idea. Men carry off women in Rape of the Sabines style, and images of intercourse--earlier brief, casual, and affectionate—mount to an extended explicit coupling of some violence that both participants appear to relish. (Is there a pc agenda at work here?) Still, the motif of the anonymous ensemble, activated but essentially purposeless, recurs frequently, often as a lineup of the full cast moving across the stage like a windshield wiper, clearing it of specific events and feelings. And yet, and yet . . . even in these essentially uninflected lines, you spy a couple arm in arm, because humanity can’t do without one-on-one bonding and can’t help telling stories (or at least, to the watcher, appearing to do so).

Watching is RAIN’s watchword. At intervals the dancers arrange themselves in a flat frieze and gaze directly at the audience. There’s nothing confrontational in this; it’s just an acknowledgement that they know you’re there—freighted, however, with the implication that, if you weren’t there watching, they and their doings wouldn’t exist. The audience might be God; the dancers, the world s/he created. The performers keep stopping for a nanosecond to look frankly and pointedly at one another, too, and seem pleased by what they see. Adam and Eve? Whenever the choreography focuses on the doings of just a few of the group, other members of the little tight-knit tribe gather on the sidelines to observe. The lookers-on are neither sympathetic nor cruelly impassive; they are simply there, bearing witness with enigmatic calm. (Oddly enough, there are similar happenings in Balanchine’s Serenade, but that is another story.)

About three-quarters of the way through De Keersmaeker’s venture, the dancers begin to emit wordless cries of exertion and excitement. These raw, guttural vocals lead to their escaping from their cage. They plunge recklessly through the cord curtain that contained them to invade the musicians’ space, then surge back into their own, as if the original boundaries agreed upon for performance had proved inadequate or artificial, limits crying out to be destroyed. As the dancers’ behavior grows more and more transgressive spatially, their dancing aspires increasingly to Dionysian intensity, until the music climaxes and halts. Stilled by silence, they animate the curtain that enclosed them with one final wave-like slash and vanish, perhaps en route to an alternative universe.

The message here would seem to be that, ultimately, the life force can’t be controlled, not even by whatever gods may be. De Keersmaeker, though, is clearly in control—she’s a deft calibrator—and it’s this evident calculation in the staging, this canny use of both traditional and postmodern theatrical devices, that makes Rain more a clever synthesis of latter-day dance theater explorations—a summary of and perhaps even a conclusion to them—than a blazing, gratifyingly discomfiting breakthrough.

Photo credit: Stephanie Berger: Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker's Rain

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

George Piper Dances / Joyce Theater, NYC / November 4-9, 2003

George Piper Dances, at the Joyce through November 9, is named for the conjoined moniker-in-art of Michael (middle name: George) Nunn and William (Piper) Trevitt. The pair of Brits with charm to spare and an unexpected taste for austere, ostensibly cerebral choreography are also known as the Ballet Boyz, after the title of a popular T.V. series they did on dancers’ backstage and offstage lives (a subject of enduring public curiosity).

Brief chronology: Pals at the Royal Ballet’s august academy, Michael and Billy (as he prefers to be called) went on together to put in a dozen years with the parent company, rising out of the corps to the rank of First Soloist and Principal respectively. Gradually they found their jobs to be same old same old, and their discontent was exacerbated by internal roiling in the grand old institution. So off they went to do their own thing, to “make it new,” as feisty artists have longed to do since modern times began. A venture called K Ballet in Japan turned out to be insufficiently high art for them, hence George Piper, founded in 2001.

Brief chronology: Pals at the Royal Ballet’s august academy, Michael and Billy (as he prefers to be called) went on together to put in a dozen years with the parent company, rising out of the corps to the rank of First Soloist and Principal respectively. Gradually they found their jobs to be same old same old, and their discontent was exacerbated by internal roiling in the grand old institution. So off they went to do their own thing, to “make it new,” as feisty artists have longed to do since modern times began. A venture called K Ballet in Japan turned out to be insufficiently high art for them, hence George Piper, founded in 2001.

Last spring, Nunn and Trevitt worked up Critics’ Choice *****, a program of short pieces by five contemporary choreographers they admired intercut with videotaped documentation of the works’ creation—the idea being to show how each choreographer operates. The Joyce program continued the policy of offsetting the live dance numbers with hyperactive video footage that may not reveal all that much about the creative process but vividly presents the Ballet Boyz as regular guys, modest and dedicated to their work, at the same time wry and irreverent—in other words, apt candidates for popularity.

Five dancers performed the Joyce bill of three strenuous works: Trevitt and Nunn, along with Hubert Essakow (another ex-Royal) and a pair of killer-chic women from elsewhere, Oxana Panchenko and Monica Zamora. The dances were uniformly abstract, with long monotonal stretches and minimal affect—a programming flaw guaranteed to make the most resolute modernist sensibility succumb to a momentary longing for a story, a recognizable character with a self-evident problem, even a swan.

William Forsythe’s 1984 Steptext, which opened the show, stated the adamantly non-objective aesthetic that was to prevail. Set to shards of a Bach chaconne, it glamorizes ferocious mean-mindedness. The dancers labor arduously in isolation, handsome and fraught, or in couple work that masks deft physical cooperation with a confrontational attitude. A repeated motif consists of raising the arms, right-angled at the elbow, and beating the fists together. Someone—the other guy, the whole goddamn world—is angling for a fight. Much of the action suggests the disjunctive dancing that takes place in rehearsal—isolated bits and pieces that cut off abruptly, impatient waits for musical cues, frustrating passages of partnering that don’t cohere. Of course, if you’ve a mind to, you can take this stuff as a metaphor for life itself. Or, if you prefer, you can fret over the way Forsythe’s women get manhandled, despite their own tough hostility. At one point, the growing menace of silence is broken by the music, whereupon the stage lights are extinguished, and the audience sits watching a dance it can’t see.

Christopher Wheeldon, Resident Choreographer at the New York City Ballet and the rising youngish hope of the ballet community, provided the show’s most attractive piece, Mesmerics, expanded to quintet status from its earlier trio form. Set to a kaleidoscope of Philip Glass music, the dance centers on an elaborate, languorous twining of long, svelte limbs, often with the dancers splayed out on the floor. They might be underwater swimmers, even dream figures enacting a wordless romance, except for the fact that brute strength clearly underlies their grace. Erect, the dancers travel on lateral paths, arms wheeling occasionally, as if as if tracing brief moments of turbulence on an infinite timeline.

As always with Wheeldon, everything that happens is beautifully contrived, carefully placed in a scrupulous architectural structure. The piece maintains its look with a consistency you’ve got to admire, yet this thoroughgoing adherence to pattern suggests an unfortunate cousinship with sleek interior decoration. Although the piece eventually achieves some mounting intensity, little happens that’s unexpected, nothing occurs to disturb the universe as the choreographer first proposed it. I admire Wheeldon’s skill, but I distrust his impulse. To me, all his exquisitely crafted dances seem to be fashioned from the outside in. They may look terrific, but they fail to accomplish one of art’s first duties—shaking up the mind or the heart.

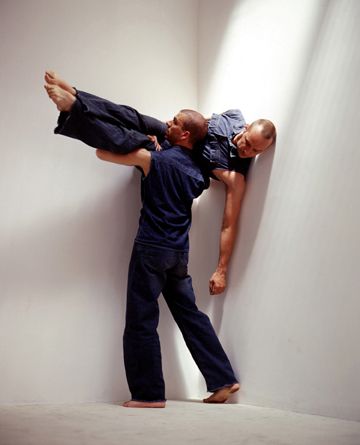

A duet for Nunn and Trevitt, seemingly based on the dancers’ close friendship, Russell Maliphant’s Torsion relies on that oh-so-yesteryear tactic of combining movement genres that (1) have little in common and (2) are absent from the curriculum of traditional dance academies. Contact improvisation dominates here, seconded by devices from capoeira, hip-hop, yoga et al. The friendship business goes on forever, oddly blue in tone, as if togetherness were impossible to maintain or reclaim, and dismayingly dependent on the partners’ alternately outstretched and clasped hands. And here we were thinking, from the upbeat sophomoric humor of those videos, that the boyz were going great, their bond so firm and cheerful. If the audience is not to confuse life and art, then George Piper should not employ strategies encouraging it to do so.

Things to know, if you believe the folks who say that GPD represents the future of classical ballet, an art they claim is dying on its feet: (1) Classical ballet is a technique that can serve anywhere. Wheeldon is essentially operating in it, using newfangled stuff largely as ornament. Forsythe seizes parts of it as his heritage then proceeds to conduct an ongoing argument with it, sometimes with inventive results. Even Maliphant, with his polyglot, anti-Establishment movement vocabulary, falls back on it when he thinks you’re not looking. (2) Classical ballet is also an art form that, like opera, is most itself when it can operate with a goodly number of performers in a sizeable house. The court ballets of Louis XIV’s era, the ballets of Petipa, and most of Balanchine’s and Ashton’s memorable works depend on generous dimension and on a hierarchy that distinguishes among principal, soloist, and ensemble ranks for choreographic purposes. Corps de ballet, remember, may be translated as “body of the ballet” and the power of a group moving in unison is not to be underestimated (as military parades prove). To be sure, there are unforgettable chamber-scale ballets (think of Ashton’s Monotones), but a repertory consisting solely of small numbers, even if they’re gems, offers its audience a very limited experience.

Another thing to know: Even with the purest of intentions—for the sake of argument, let’s credit the Boyz with these—it may be impossible to engage a broad audience with highbrow “advanced” choreography. Mikhail Baryshnikov had a splendid go at it for some years with his White Oak Dance Project on the strength of his name and his gifts as a dancer even after age and injury eroded the virtuoso aspect of his powers. But, to paraphrase Lincoln Kirstein—who masterminded Balanchine’s career, to say nothing of the development of the New York City Ballet as an institution—ballet is simply not destined to interest as many people as football does. There are indeed ballet moms as well as soccer moms, but a huge difference remains in their numbers. While George Piper Dances is fine and dandy, Nunn and Trevitt might do well to concentrate their considerable talents and energies on expanding the scope of their repertoire instead of trying to make themselves household words.

Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning: Michael Nunn and William Trevitt in Russell Maliphant’s Torsion

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

American Ballet Theatre / City Center, NYC / October 22 - November 9, 2003

American Ballet Theatre's annual fall season at City Center, now expanded from two weeks to three, looked foolish even before the curtain went up.

A new marketing ploy organized the repertory being offered into four set programs. The most misguided of them, "Innovative Works," served up Nacho Duato's Without Words, William Forsythe's workwithinwork, and Within You Without You: A Tribute to George Harrison, choreographed by various hands, including David Parsons, who has a deft finger on the pulse of popular taste. "The W Show," as I came to think of it, restricted itself to presenting dancers clad for today--in unitards, low-slung jeans, and gloom. I assume it was designed for folks who feel threatened by tutus. Only the Forsythe piece, a strong, concise example of his post-Balanchine style, was worth a moment of one's time.

This inflexible system all but guaranteed the annoyance of potential ticket buyers with some knowledge of the art. For instance, Balanchine's diamond-brilliant celebration of classical dance Theme and Variations could be seen only at the opening night gala or the "Family Friendly" matinees, occasions that tend to be undermined by restless audiences (the all too rich and the all too young). It created a few delicious absurdities as well. Agnes de Mille's charming revue-style romp from 1934, Three Virgins and a Devil, also relegated to gala/matinee position, may well have entertained underage spectators, but surely it occasioned a dubious instructive opportunity: "Mommy, what's a . . . ?"

The issue of virginity also dominates Antony Tudor's 1942 Pillar of Fire, given the imprimatur of placement on the "Master Works" program, as if its being one of the twentieth century's most potent dramatic ballets--a searing essay on sexual repression, revolt, and redemption--were an insufficient guarantee of its worth. Donald Mahler, apparently the official purveyor of Tudor to ABT, staged this revival, and I attribute its failings largely to him. His productions of Tudor, attentive to detail, invariably lack a governing theatrical impulse. Watching them is like looking at a picture painted by numbers. The discrete images are there, but they don't quite cohere, and they don't seem driven by an intense vision. I wonder if Sallie Wilson, once a notable ABT interpreter of Tudor roles, who now mounts Tudor's choreography elsewhere, might be more capable of restoring the essential dynamics to this ballet.

Granted, the present time has not cultivated dramatic dancers like Nora Kaye, who originated the role of Pillar's tormented heroine, Hagar, and brought to it a turbulent force at once physical and psychological. Gillian Murphy, distinguished by her grandeur of body and technique, is promising in the part, but as yet almost adamant in her refusal to let Hagar's situation and feelings engulf her. Julie Kent--an ethereal beauty, and thus cast against type--is naturally too fragile in style (Hagar's plight is not an occasion for delicacy) and, like Murphy, too placid, almost immune to what Tudor tells us is going on. Toward the end of the ballet, though, she offered a glimmer of authentic feeling. (I'm writing this before Amanda McKerrow takes her turn in the role.) In both casts I saw, the character of Hagar's male foils--the one who offers her sex (Marcelo Gomes; Angel Corella) and the one who offers her sympathy and a future (Carlos Molina; David Hallberg)--hadn't cohered. Only Xiomara Reyes, as the little minx of a younger sister, is already perfect in her part.

Granted, the present time has not cultivated dramatic dancers like Nora Kaye, who originated the role of Pillar's tormented heroine, Hagar, and brought to it a turbulent force at once physical and psychological. Gillian Murphy, distinguished by her grandeur of body and technique, is promising in the part, but as yet almost adamant in her refusal to let Hagar's situation and feelings engulf her. Julie Kent--an ethereal beauty, and thus cast against type--is naturally too fragile in style (Hagar's plight is not an occasion for delicacy) and, like Murphy, too placid, almost immune to what Tudor tells us is going on. Toward the end of the ballet, though, she offered a glimmer of authentic feeling. (I'm writing this before Amanda McKerrow takes her turn in the role.) In both casts I saw, the character of Hagar's male foils--the one who offers her sex (Marcelo Gomes; Angel Corella) and the one who offers her sympathy and a future (Carlos Molina; David Hallberg)--hadn't cohered. Only Xiomara Reyes, as the little minx of a younger sister, is already perfect in her part.

Another masterwork, a revival staged by Wendy Ellis Somes of Frederick Ashton's 1946 Symphonic Variations proved to be the chief of the season's pleasures. This infinitely serene dance for six, set to César Franck's Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra, is about as abstract as dance can get. Nevertheless, it projects a strong atmosphere of hard-won serenity, of calm after storm, of people resuming their communal lives after devastating disruption. The date of the work--1946--is a clue to the meaning embedded in the choreography. When, as they periodically do, the dancers run in a serpentine pattern across the stage, linking hands as they travel to form an ephemeral human chain, it would be hard not infer a message about life's fragility and the unquenchable human desire to reclaim territory and connections after even the gravest violence has been done to them.

However one chooses to interpret the dance, its overall effect is one of sublimity. This is odd, considering how much of the movement in Symphonic Variations is most peculiar. Time and again, the use of the arms and hands systematically contradicts balletic convention. The arms frequently extend straight from shoulder to wrist instead of rounding softly. They thrust athwart the torso rather than graciously framing it. They shield the head, masking expression. The hands stray from their prescribed cupped position, fingers arranged like tendrils, to an emphatically closed, flat one, sometimes sharply angled from the wrist. Even odder is the fact that these deviations from the classical norm actually blend in with the lovely acquiescence to its rules that prevails in the ballet, the new and strange being absorbed into the old and, what's more, enhancing it. Is Ashton giving us an illustration of how the academic dance ballet vocabulary has evolved?

Every member of the first cast (the second hadn't performed at press time) looked dedicated to getting the dance right, and the purity and steadiness of this aspiration was, in itself, infinitely touching. Thus far, Ashley Tuttle, an exemplar of the classical style in its gentle mode, is the only one in the sextet to achieve the illusion of repose ideal for the choreography. Her accomplishment is evident both in the harmony and composure of her dancing and in the moments--one of the ballet's most telling motifs--when she's utterly still, like a breathing statue or a Zen practitioner, just being. Tuttle's role was originated by Margot Fonteyn, and her rendition of it, though utterly free from the strains of imitation, serves as a homage to her predecessor.

Providing a certain requisite dazzle, the company offered an excerpt from Marius Petipa's 1898 Raymonda. Staged by Anna-Marie Holmes, who specializes in the nineteenth-century Russian classics, and ABT's artistic director, Kevin McKenzie, the ballet is slated for performance in its full-length guise during the company's 2004 spring season at the Met.

Over at the New York City Ballet, George Balanchine, who, at various times, excerpted the segments of Raymonda that remain viable for a contemporary audience, seemed fully aware that, despite its glorious Glazounov score, the whole show, with its murky narrative set in medieval Hungary, will no longer fly. ABT, from earlier attempts of its own to resurrect a surround for the indisputably marvelous passages in the choreography, should know this too. Maybe some audience survey, revealing the general public's yen to be told a story in a lavish setting, persuaded ABT's management to try again. (Management has never been known for a firm aesthetic stance.)

This season gave us a preview of the upcoming production, the "Grand Pas Classique," which provides legitimate occasions for that ABT specialty, male pyrotechnics, along with the show-offy glamour of svelte, smiling beauties arrayed in fur-trimmed tutus. More important, it contains splendid choreographic inventions--a solo for the ballerina that's inflected with signature moves from the czardas; a male quartet based on the camaraderie and competition at the heart of male bonding; and experiments with the hierarchical distinction between soloist and ensemble that are strikingly forward-looking.

Things weren't going too well yet at the performances I saw, one led by Paloma Herrera and Jose Manuel Carreño, the other by Michele Wiles and Carlos Acosta. The text for the male lead's big solo seemed to adhere to the instruction "Don't worry, it's not set in stone. Just do your flashiest steps." The pas de quatre guys, having established a gracious, genial relationship, flubbed the series of double air turns that's the element everyone remembers from their material. Meanwhile, the ballerina role is crying out for intensive coaching from Martine van Hamel, who, in earlier ABT versions, embodied just the right dual image for Raymonda: tsarina of Imperial Russia and gypsy full of secrets, many of them erotic.

On the "Contemporary Works" program, a matched pair of acquisitions created by the celebrated Jirí Kylián, whose home base is the Nederlands Dans Theater, were juxtaposed with a home-grown novelty, Robert Hill's Dorian. Hill has taken as his springboard Oscar Wilde's macabre, titillating tale in which a narcissistic man remains young and beautiful in appearance while his portrait registers the progressive corruption of his soul. The family unfriendly subject matter is undeniably tempting, but Hill simply doesn't possess sufficient craft to re-animate--in terms of ballet--the narrative, the characters, or the lusciously decadent mood of his literary source. The mime necessary to convey the scenario is not so much acting as "sort of" dancing, which leaves matters vague, while the set pieces of dancing, which should spring from the story line like aria from recitative, are so thin, pallid, and predictable as to seem nonexistent. In the course of the near hour it took for Dorian and his doppelgänger to come to their horrific end, I couldn't help wondering, What would Antony Tudor have done?

Despite follies of programming, casting, and coaching and the perennial tug between the concerns of commerce and those of art, the ABT season repeatedly delivered little miracles. One instance of utter perfection: the Cornejo siblings, Erica and Herman, as the Couple in Yellow in Martha Graham's Diversion of Angels. Light, swift, exuding joy--working, rightly, from a gut-sprung base--they equal, perhaps surpass, the finest Graham-bred exponents of the roles that I've seen. On them, the choreography that classical dancers struggle with because it is basically alien to their training suddenly, astonishingly, looks spontaneous.

Photo: Marty Sohl: Marcelo Gomes, Gillian Murphy, Erica Fischbach, Xiomara Reyes, and Carlos Molina in Antony Tudor's Pillar of Fire.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary