Seeing Things: October 2003 Archives

Susan Marshall & Company / BAM Harvey Theater, New York City / October 21-25, 2003

In our current climate of branding, dance concerts must have titles.

The choreographer Susan Marshall, already branded as a genius by her copping a MacArthur Fellowship 2000, slyly called her latest program, part of BAM’s Next Wave series, Sleeping Beauty and Other Stories. The words on both sides of the (pointedly unitalicized) “and” are simply the names of her two newest works. The first is one of the finest efforts of her career.

Like the landmark Marshall pieces Interior With Seven Figures (1988) and Arms (1984), Sleeping Beauty, while pretending to be abstract, evokes the poignancy of the human condition. It takes as a given the darkness in which we all operate, acknowledges the basic futility of human relationships, yet charts (and celebrates, I think) the persistence with which we doggedly continue trying to make them work—as if our identity depended upon the hope-fueled effort. All of this is done so unemphatically, with so much sheerly visual gratification along the way, you hardly know what’s happening to you until the piece ends and your emotional experience has been so profound, you can barely move or speak.

For Sleeping Beauty, Douglas Stein has provided a stern beauty of a set. Multi-paned crackle-glass panels partition the space, creating an open field framed by semi-private corridors. Through the panes, tiny windows offering different degrees of translucency, both dancers and viewers can see variously—fully, partly, or not at all. Huge work lights hang high above the dancing ground, suggesting, despite the austerity of environment, the chandeliers Perrault might have given Aurora’s palace. The scene is subtly and eloquently lighted by Mark Stanley (who surely deserves a MacArthur of his own).

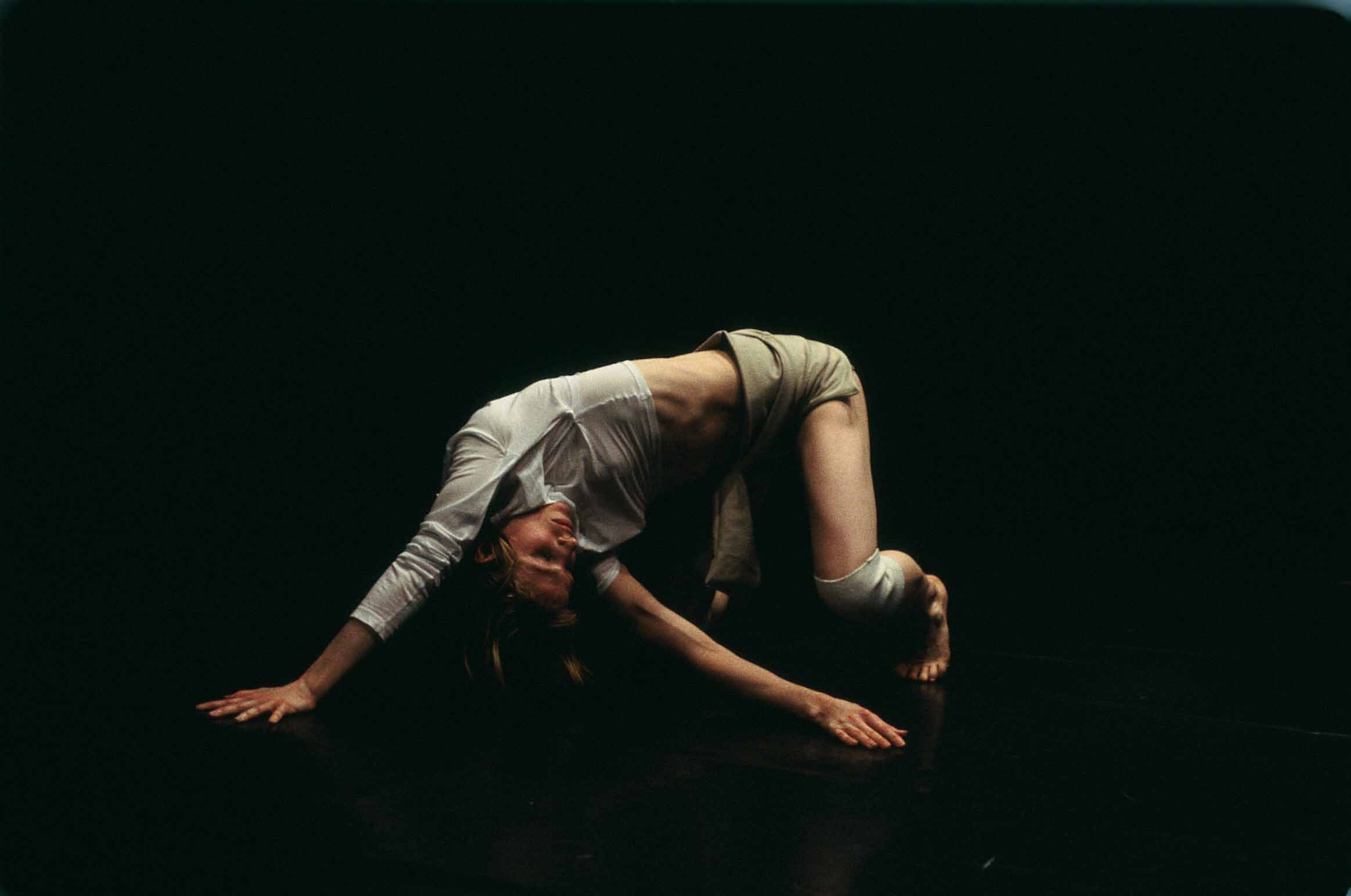

The focal point of the choreography is a young woman, the pale, grave-faced, Kristin Hollinsworth, distinguished for her long-limbed flexibility and grace. Surrounding her is the small crowd one might call family or society. Movement motifs define the girl’s difference and strangeness: Her arms and legs stretch, oddly angled, as if to shield her from view or point to a faraway nowhere; her whole body, held off-kilter, falls into fits of stasis as if she were absorbed in a dream. She is luminous in her isolation, and inscrutable. (Doesn’t this lie at the heart of being a princess—remaining aloof and apart from the ordinary run of humankind?) The crowd insists upon making her one of them.

The focal point of the choreography is a young woman, the pale, grave-faced, Kristin Hollinsworth, distinguished for her long-limbed flexibility and grace. Surrounding her is the small crowd one might call family or society. Movement motifs define the girl’s difference and strangeness: Her arms and legs stretch, oddly angled, as if to shield her from view or point to a faraway nowhere; her whole body, held off-kilter, falls into fits of stasis as if she were absorbed in a dream. She is luminous in her isolation, and inscrutable. (Doesn’t this lie at the heart of being a princess—remaining aloof and apart from the ordinary run of humankind?) The crowd insists upon making her one of them.

Together the two camps, Herself and The Others, perform the activities of rehabilitation. Again and again, the girl’s often unresponsive body is positioned into the anatomical positions that mean contact (even the small interactions so-called normal folks take for granted), communication, lust and its aristocratic cousin, love. Occasionally the girl initiates the exercises herself; sometimes her would-be rescuers, losing patience, bully her into the process; otherwise the action, even when physically fraught, exudes a clinical serenity. Whatever the emotional atmosphere, the result is always the same. The girl’s body halts; passive and flaccid, it drops from her would-be helpers’ arms. As both sides give up for the moment, the girl moves away with an air of a hurt bafflement, retreating into her chamber of living death. (Once in a while, though, there’s a flicker of stubbornness about her response, a glimpse of the madman’s will to persist in his madness because it constitutes his only security.) Inevitably, heroically, both sides keep coming back for another go.

The saddest thing about the circumstances Marshall depicts is that the afflicted girl seems (though only seems, and only intermittently) to want to join in the flow of common life, to be part of a social world, to connect. But, despite repeated effort, both heartbreaking and exasperating in its futility, she can’t—and both she and the people concerned with her plight are doomed to not knowing why. Or is the saddest thing, after all, the fact that, increasingly as the piece progresses, the crowd reveals itself to be simply a collection of people like the girl, the difference in their condition being merely one of degree, not kind? In the closing image, both heroine and nameless crowd, the ostensibly maimed and the ostensibly whole, lie outstretched on the ground, rolling back and forth in a horizontal line, like wind-whipped ocean waves in an eternity of sameness.

Other Stories, the companion piece to Sleeping Beauty, is dutifully joined to its partner on the program by its opening image: a woman’s body lying supine on a raised plinth, illuminated by a glaring shaft of light on an otherwise dark stage. But the piece quickly moves on to its own concerns, revealing, in edgily fragmented sightings, seven hyperactive characters in search of an auteur to provide them with one of drama’s basic necessities: narrative—or at least dilemma, or at the very least situation.

As it is, they’re merely fugitives from the stage that is perennially set for dreams when we sleep, or perhaps the lurid personae that spring from the synthetic sleep of anesthesia (think of the old term “operating theater”), or souls lost in the outtakes of a movie doomed to failure from the start. Their antics—shards of high (melo)drama, surreal opera, and vaudeville, along with the frantic chaos invariably attendant on theatrical enterprises—seem to go on for a century, gradually relinquishing their right to our attention. I think the piece is supposed to be funny, and the opening night audience did chortle cooperatively a few times, but Marshall, who has a look of Garbo about her, doesn’t laugh with confidence or ease.

The one terrific thing about Other Stories is the costuming, by Kasia Walicka Maimone, who has served Marshall long and well, but usually, as in Sleeping Beauty with subdued lyricism. Here the costumes are a medley of wildly fanciful finery borrowed from the worlds of princess, slut, and itinerant entertainer—garb for a poetic Hallowe’en.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Merce Cunningham Dance Company / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, New York City / October 14-18, 2003

Dancing usually hangs out with music—and with good reason. Think rhythmic, structural, and atmospheric support. Think Tchaikovsky-Petipa; think Stravinsky-Balanchine. Merce Cunningham, celebrating the 50th anniversary of his company at BAM this week, was a pioneer in disconnecting the two arts, inviting them to exist in the same place and time yet avoid co-dependency.

With avant-garde practitioners like John Cage, Cunningham evolved the policy of commissioning composers to provide a score of a specific duration (giving them no other parameters or clues to his own intentions), while he created choreography of the same length. Music and dance met only on opening night of the production. So it was not entirely astonishing to learn that a pair of forward-leaning rock bands, Radiohead and the Icelandic Sigur Rós, would provide the sound for Cunningham’s newest work, Split Sides, the ostensible climax of an event-filled anniversary year, though the choreographer usually goes for more highbrow types. But rock commands an audience and BAM, like any other producing organization, needs to sell tickets.

It should be mentioned here that the use, in productions featuring contemporary choreography, of musical and visual artists who will attract their own crowd to the performance is nothing new at BAM. Indeed, this shrewd blend of avant-garde elements, historically related to holes in the wall, with astonish-me spectacle has been a regular practice of the house’s Next Wave series since its inception in 1983. Some of the combinations have been truly organic, the happiest, perhaps, being the teaming of Philip Glass, Robert Wilson, and Lucinda Childs for Einstein on the Beach. Others have been contrivances with an opportunistic air. Fortunately, in Cunningham’s case, given the persistent integrity of his work and his personal dignity (a mix of modesty, piercing intelligence, and wit), nothing the man is involved in looks cheap or merely canny.

Nevertheless, in addition to the musical choice made regarding Split Sides, other aspects of the dance’s construction turned venerable Cunningham practices into publicity stunts. Most important was the roll of the dice, an I Ching practice that allows chance, through its random effect, to enlarge one’s sphere of action beyond the narrow, prejudicial dictates of personal choice. For the 40-minute Split Sides, Cunningham created a pair of 20-minute dances and ordered up two backdrops, one each from Robert Heishman and Catherine Yass, and two sets of costumes and lighting plots, from company regulars James Hall and James F. Ingalls, respectively. A roll of the dice before each performance would dictate the order in which the elements were used in the two-part piece. If all the journalism this adventure generated could be turned into a $100 grant per word, Cunningham might never have to go begging again.

For the opening night gala, attended by a packed house of the rich, the famous, and the curious, augmented by squads of rock music fans and their Cunningham-reverent equivalent, as well as an extra component of security folks, the dice rolling was done onstage, in the presence of the musicians who would later be hidden in the pit and a few dancers picturesquely warming up. It featured New York’s Mayor Bloomberg at his most aggressively exuberant (to compensate for Cunningham’s decades of under appreciation?), with the rolling done by celebs like former Cunningham collaborators Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cunningham ur-dancer Carolyn Brown.

Eventually, after all the brouhaha, here it was, another Merce Cunningham dance, and this time, as chance would have it, not a particularly distinguished one. Following the dictates of the dice, the first segment used Part A of the choreography, Radiohead’s accompaniment, Heishman’s backdrop (like Yass’s, a pale blow-up of an abstract photo), and Hall’s black and white costumes (hyperactively scribbled-over unitards) as opposed to the ones aggravated with psychedelic tints; the second segment, the alternatives.

Neither sound score was what devotees of, say, Bach—favored by choreographers of various persuasions—would call music. Yet neither, though far less intellectually sophisticated than the work of, say, John Cage, was radically different, in effect, from the aural accompaniment Cunningham has traditionally provided for his dances. Hazard determined whether or not, at any given point in the proceedings, it meshed with the movement or served as a maddening distraction. Both Radiohead and Sigur Rós laid down a background of hypnotic New Age chimes-and-gongs (music to space out on), agitating it with the static of indecipherable speech, mechanical noise, and threats from nature (thunder, the buzz of swarming insects). Presumably the competing, fragmented sounds and rhythms reflected the contemporary mindset. To my ears—untutored in such matters, I grant you—all of it sounded terribly dated. Ignoring its hovering partner, the movement went serenely about its business.

Unfortunately, that business seemed to be a simplistic version of what Cunningham usually does—as if, having lured in a crowd unfamiliar with the sort of dancing he’s evolved in the last half century, he'd made his work more readily accessible. This friendly but artistically diminishing impulse was most evident in the structure department. Cunningham habitually composes long, flowing ensemble passages, streams of dance that seem capable of going on forever. Within these, an individual viewer is free to highlight, through his attention, the action of smaller groups. As if the choreographer had been reluctant to tax the patience of neophyte watchers, Split Sides makes a clear distinction between brief stretches of group movement decidedly reduced in complexity and solos, duos, trios, and so on that stand out—sharp and self-contained—like vaudeville turns. (The opening night crowd applauded several of them with relish.) What’s more, although Cunningham rarely dictates tone, there seemed to be several deliberately humorous patches—playful, even arch arrangements for twos and threes in which the dancers flirted and clowned like figures from some postmodern commedia dell’arte. I felt as if I were watching Cunningham 101, though that imaginary course would, more appropriately, consist of 20 minutes chosen at random from any of the choreographer’s masterworks and viewed in a state of calm receptivity.

For me, the treat of the evening was the 2002 Fluid Canvas, being given its New York premiere. In it, Cunningham's 15 dancers, ravishingly lighted by James F. Ingalls, epitomize their breed. They’re a highly refined race noted for fluidity, fleetness, psychic as well as physical harmony in the most off-kilter positions, high alertness, and deep concentration. Several of the beautiful glimmering unitards—in gunmetal and aubergine—that James Hall designed for the piece are cut deep to the waist in back, and it was a surprise to see, not five minutes into the action, the gorgeously muscled flesh glistening with sweat, because the figures seemed superhuman creatures for whom effort was unnecessary.

The choreography makes much of unusual postures, sometimes with so much torque to them and such anti-intuitive arrangements of the arms, the dancers look like gargoyles—albeit extraordinarily handsome ones. At the same time, Cunningham allows the upper body to contradict its lower half, so that two very different kinds of activity are going on at once. These explorations do not so much refute classical ballet (which plays a much larger role in Cunningham’s resources than, say, the modern-dance inventions of Martha Graham, with whom once he danced) as they investigate, with a sympathetic curiosity, the reverse of its coin.

More typically of Cunningham—though more emphatically than usual—Fluid Canvas calls our attention to the varying numbers of dancers on stage at a given time. It also makes us acutely conscious of negative space. The voids created on the stage are as potent as the areas filled with human bodies carrying out a wide and subtle range of ever-shifting designs. Towards the end of the piece, the dancers sit hunkered over their own bodies, heavy and one with the earth, it would appear. Suddenly, they help each other up and rush swiftly, light as windswept autumn leaves, into the wings. Once they’ve vanished, the stage remains empty for a few seconds, just long enough to let the emptiness register, then the light is extinguished and the curtain falls. The dance isn’t over, Cunningham instructs us, until our eyes and minds take in the significant condition of not-dancing.

Photo credit: Jack Vartoogian: Daniel Squire and Holly Farmer in Merce Cunningham's Split Sides

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

"Yasujiro Ozu: A Centennial Celebration" / Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater, NYC / October 4 - November 5, 2003

Dance aficionados as well as film connoisseurs will be drawn to the Walter Reade Theater for the Film Society of Lincoln Center's "Yasujiro Ozu: A Centennial Celebration," October 4 - November 5. The lure for the dance crowd? The iconic director's insight into movement and his rendition - always sensitive and frequently sublime - of feelings that lie past the reach of words.

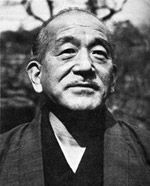

Those just glancingly acquainted with the work of Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963), as well as his committed fans, characterize the Japanese film director as the master of non-action. At heart, his films concern themselves with being, not doing - an attribute of the Zen thinking with which his outlook is allied. Ozu embodied the quality of transcendent stillness most perfectly in his middle period - extending from the mid-thirties to the mid-fifties - once he had, somewhat reluctantly, adopted sound, but before he had, with equal reluctance, succumbed to color. (His earliest films, enchanting silents, are often highly animated.)

Those just glancingly acquainted with the work of Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963), as well as his committed fans, characterize the Japanese film director as the master of non-action. At heart, his films concern themselves with being, not doing - an attribute of the Zen thinking with which his outlook is allied. Ozu embodied the quality of transcendent stillness most perfectly in his middle period - extending from the mid-thirties to the mid-fifties - once he had, somewhat reluctantly, adopted sound, but before he had, with equal reluctance, succumbed to color. (His earliest films, enchanting silents, are often highly animated.)

Creating a peerless series of black and white "talkies" over two decades, Ozu probed the extraordinary ways in which limitation can serve to reveal the intangible (and most significant) aspects of existence, focusing the attention on essences rather than events. One of his most apparent means was stasis: minimal body and facial movement for the actors (emoting was thus precluded) and a fixed position for the camera, which then regarded the material before it like the unwavering eye of God. What is most curious about this denial of motion is the tremendous importance motion assumes when it does occur. Like that of very different masters - Balanchine, Ashton, and Tudor - Ozu's "choreography" creates epiphanies by manifesting intense, unarticulated feeling through physical action. And it does so in remarkably varied ways.

In the 1953 Tokyo Story, as is typical of the mature Ozu, plot has become as fragile and translucent as a silver-penny petal. The film is dominated by a theme that obsessed Ozu throughout his career: the nature of human experience as it is expressed in the relationships between parents and their grown children.

An aging pair make a momentous visit to the big city where they find their adult offspring largely too preoccupied with their own concerns to give them the loving respect and attention one might assume to be a parent's due. Resigned to their disappointment, they journey home, whereupon the mother succumbs to a stroke and lies unconscious on her deathbed. Ironically too late, the children gather in attendance around her pallet. Although charged with feeling, the scene - with the inert body at its center - is utterly quiet and self-contained. It's almost a still life, the actors and the camera are physically so subdued.

The younger brother arrives after the others, explaining he'd been away on business when the summons came. He's literally too late; while the camera gazed outward to the town, the sky, the river - the larger, sentient universe - the mother expired. By custom, her face is covered with a square of white cloth. "Look at her," an elder sibling urges the latecomer, "she looks so peaceful." The son moves to lift the cloth and, with typical Ozuian obliqueness, the camera - its rhythm as unforced and acutely timed as a sleeping child's breath - cuts away. So we don't see what the son sees - the mother's placid face in death. We don't need to. It already exists in our imagination. Nor do we see the son's face; Ozu would consider even such a minor bit of melodrama tactless both emotionally and aesthetically. Instead, he slews the camera around to the other figures' response, a kind of visual harmony to the unrecorded event. Kneeling, passive as hills, gazing down at their hands, they lift their heads to witness their brother's sight, then, as one, incline slightly from the waist and neck, instinctively bowing to the sacredness of the moment.

This passage from Tokyo Story epitomizes the beauty and deftness with which Ozu makes his primary emotional point through a single move - the bow - in an environment of physical and emotional quiescence. In The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice (1952), the climactic scene is based upon a journey - geographically minute and on domestic turf, poetically immense and structured as formally as a classical ballet. An estranged husband and wife, having reached the point of reconciliation, penetrate by stages into the core of their home, the kitchen. A modest room at the back of the dwelling, down several stairs, it fulfills a basic human need - hunger - yet this long-wed couple hardly knows where it is. (The erotic parallel is obvious, though it's not in Ozu's nature to belabor it.)

The husband is a simple man - blunt, good-hearted, tenaciously unaffected. His taste is for the common, unpretentious things of his background. They fit him, he explains at one point, later amplifying his observation: "It's how a married life should be." Superficially sophisticated, disappointed in the dullness of their union, his wife has rebuffed him for his lack of refinement. Now, having learned through pain to understand and appreciate each other, they celebrate by going in search of a midnight bowl of rice doused in green tea - a peasant meal, typically consumed with slurping relish.

The kitchen is hidden, almost unknown, territory to this comfortably-off pair, but to preserve the intimacy of their newfound accord, they choose not to summon their sleeping maid to serve them. Side by side, touching each other so lightly and unemphatically, their physical contact is barely visible, they slide back the wall panel of their living room, pass through a narrow, dimly lit corridor, slide open yet another panel, and illuminate a primitive hanging lamp that discloses the humble kitchen so mysterious to them. Together, they prepare their repast - he gently draws back her kimono sleeve as she washes her hands - and return by the same route, soft-edged shadows on the translucent panels they shut behind them.

Their journey - with its unstressed sexual parallel - is one of venturing by degrees, of lifting veils and entering uncharted passageways. As it progresses, the bourgeois environment and the bourgeois situation dissolve into evocations of legendary quests: Orpheus descending into the underworld in search of Eurydice, the prince of Perrault's Sleeping Beauty crossing the barriers that separate him from his heart's desire.

Late Spring, made in 1949 and perhaps Ozu's most exquisite achievement, uses an image of nature in motion to express human feeling. The tale - again, one that Ozu reiterated as if he could never be done with the issue - concerns a widower who realizes he must release his beloved and devoted daughter from tending him into a life of her own. She's reluctant to leave the serene, secure shelter of her girlhood, so he deceives her into thinking she must marry because he wants to remarry. The idea of her father's entering into a sexual alliance after her mother's death revolts the young woman. Matters come to a crisis at a Noh performance, when the daughter sees her father exchange gazes with the lovely widow who will presumably appropriate her place.

This being an Ozu film, not a word is spoken directly about the matter, but the daughter's swiftly mounting feelings of anger and desolation are clear, almost unbearable in their repressed intensity. The theater scene ends and, as is Ozu's custom in shifting locale, a landscape shot is inserted. Technically, it's a transitional device; aesthetically, it's a container for human emotion so dense and many-faceted it can't be particularized. Several such shots, earlier in this film, showed a few thin, barren tree trunks. Now Ozu's camera looks up at a flourishing tree, proudly set against the blank sky. At the peak of its maturity, the tree is wide and thickly branched, in full leaf. A wind blows through it, making its foliage dance in the sunlight, as if to emphasize its vitality, and its already luxuriant expanse seems to inflate, like a lung. The tree - whether you take it to be just a tree or a symbol of unquenchable, continuing life - is breathing. The breath is the breath of immanence.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

This week's performances of Ballett Frankfurt at the Brooklyn Academy of Music mark a critical stage in the career of William Forsythe, who has shaped the company according to his singular aesthetic. I've invited the dance writer Roslyn Sulcas, our New York expert on Forsythe, to provide some background. Here is her report:

William Forsythe has been quietly enlarging the world of classical dance over the last two decades. Born in New York, and trained at the Joffrey Ballet School, Forsythe moved to Germany in his early twenties to join the Stuttgart Ballet and has lived there ever since. Although he has been a major presence on the European dance scene since Rudolf Nureyev commissioned In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated for the Paris Opera Ballet in 1987, it is only during the last few years that he has become better known to an American dance public, as companies nationwide have acquired works like In the Middle, Herman Schmermann, and The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude.

More frequent tours to New York in recent years have also meant that Forsythe has been able to show in greater depth the elaborate movement vocabulary that he and his dancers have developed during his tenure in Frankfurt, alongside the inventive theatricality and creative use of lighting that characterize his work. Even if it often strays from ballet’s emphasis on lengthened line and effortless virtuosity, much of Forsythe’s work is engendered by the ideas present in the forms of classical dance. It also looks balletic because he uses classically trained dancers, whose bodies instinctively enact the formal rules (turn-out of the hips, pointed feet, the extension of the spine and limbs, epaulement) that characterize the art form, even as they deploy it in unconventional ways.

The result is dance that (among other things) disregards the vertical planes to which the classical positions of the body are fixed, uses the thrust and momentum of the dancer’s weight to alter conventional transitions between steps, deploys the upper body to generate movement rather than accessorizing the legs, and offers a complex display of coordination and counterpoint.

Sadly, the ensemble with which Forsythe has developed this distinctive vocabulary and a huge repertoire of dances will cease to exist as of June next year. The reasons for the company’s dissolution remain somewhat murky. In early summer last year, rumors circulated that a newly politically conservative Frankfurt city council, which funds the company as part of the Frankfurt Opera ensemble, was reluctant to extend Forsythe’s current contract past its expiration date of June 2004, preferring to re-establish a more conventional ballet company in the city and hoping to cut costs on an increasingly beleaguered cultural budget. (An illogical idea, if true, given the even greater expense of running a conventional ballet company.) After the media seized upon the news, thousands of e-mails and faxes from all over the world, protesting this decision, poured into the mayor’s office, prompting a statement that there was no intention to fire Forsythe. By then, however, Forsythe had decided that he didn’t want to go on in an atmosphere that was hostile to his work. (Subsequently, the city council announced that Ballett Frankfurt could continue if the budget was cut by 80%.)

The dissolution of Ballett Frankfurt is of great consequence to the dance world. Over two decades, Forsythe transformed this company into one of the most consequential contemporary ballet ensembles in the world, creating dances out of a profound body of deeply ingrained physical knowledge. Choreographers need their tools - dancers - and the best tools are those who have been honed into perfect form for the work at hand. Forsythe will, of course, continue to be sought after as a dance maker, and will no doubt go on to make important pieces; there is talk at present of his forming a smaller company that would be partially funded by the states of Saxony and Hesse. Nonetheless, those twenty years’ worth of ballets, the heritage present in the collective body of dancers, is a significant loss to the world of dance, and well beyond.

© 2003 Roslyn Sulcas

Ballett Frankfurt / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, NYC / September 30 - October 5, 2003

I wish I liked William Forsythe's work more. After Ballett Frankfurt's opening night at BAM, I felt an inch closer to appreciating it - as the enthusiastic audience, peppered with dance-world celebrities, clearly did. But no more than an inch. Yes, the vocabulary is inventive (if narrow). The pictorial sense at work is superb. The Forsythe-groomed dancers perform with extravagant energy and commitment. But the dances seem to be telling the same story over and over again - or no story at all. You watch these creations and nothing happens to you. (For "you," read "I" and "me.") This choreography doesn't galvanize my feelings; it leaves my perception of the universe intact. I walk out of the theater exactly the same person I was when I walked in. "I just don't get it," complained one of my colleagues in the second intermission, waving his hand toward the stage as if to indicate the whole Forsythe oeuvre. But he and I are in the minority.

Forsythe calibrated his program - perhaps Ballett Frankfurt's farewell to New York - astutely. Two largish group pieces framed a pair of chamber-scaled works, a women's duet and a male quartet, the public encasing the intimate. Austere elegance governed the overall effect. Minimal music, provided by Forsythe's regular sound man, Thom Willems, or silence broken only by the dancers' emphatic breathing accompanied lush, high-voltage dancing. The "scenery" consisted merely of black drops, in heavy velvet or translucent gauze. The costuming alternately reflected dancers' practice clothes and pajama-casual schmattes - the antithesis of fancy dress that's almost a moral stance these days. Talk about suave!

The Room As It Was served well as a curtain raiser since it presents Forsythe at his most typical. Eight dancers come and go, working in ever-shifting small groups or as loners tangentially connected to the "crowd." Hyperactivity - strikingly, in the torso and pelvis as well as the arms and legs - contrasts with slow swirls that twist off the vertical to spill, still writhing, into horizontal positions on the floor. Small vortexes of motion occur constantly. Sometimes they're charged with a little feeling, even a little drama; more often they look like calculated investigations into the possibilities of the human anatomy.

Images fleetingly suggesting confrontation and combat interlace with tentative, solicitous handholds, as if the participants had joined an encounter group and were sensitively trying to figure out how to get along with one another. Shards of disaffection and absurdity à la Pina Bausch surface too, as in a sequence where a fellow repeatedly attempts to plant a gentle kiss on the neck of an indifferent young woman who doesn't even bother to repulse him but merely deflects his efforts as she waits impatiently for a better offer.

Though the piece is very bright and busy, it doesn't make a dent in your consciousness until its very last moments, when a mid-stage scrim rises, doubling the depth of the available space and revealing a pair of dancers in shadow. A fragment of music is heard; it seems to announce that the show has now begun.

(N.N.N.N) - Forsythe goes in for abstruse titles - uses lots of gestures that lie (in the middle, somewhat elevated, you might say) between pantomime and dancing. When the full cast of the piece - four guys - is involved, clustered tight, with no music to help out, timing becomes a tour de force. The imagery borrows from sports, martial arts, artificial respiration, and just plain goofing around. Fighting and bonding, Forsythe seems to be saying, that's what men do, and the clue to their nature is that they do it simultaneously. Unfortunately, on this occasion, they do it for far too long. The extended proceedings begin to look aimless because, unlike Merce Cunningham - the master of going on at length without many clues to mark where we are, where we're heading, and what's happening en route - Forsythe can't make us confident that his choreography harbors an internal structure, albeit a hidden one.

In Duo, Forsythe shows us what women do - understand the aspects of life that can't be seen or explained and, via this intuition, become one with the inner workings of the world. Although it has its share of Forsythian middle-of-the-body wriggles and slews off the vertical, the movement language of this duet emphasizes long stretched limbs, diagonalled arms suggesting the hands of a clock, the swing of a pendulum. Moments of stasis, alternating with calmly paced action, lend the bodies a sculptural effect and, with that, an emotional dimension. The women seem to be allying themselves with passing time, mastering it by giving in to it.

Women can also, Forsythe observes as a footnote, dress to kill. And he has dressed this voluptuously bare-legged pair in shiny black bikini briefs, veiling their torsos and arms with the sheerest imaginable jet stretch fabric, so that the top of the body appears naked but glamorously shadowed. Having noted what a sheath of see-through black stocking can do for the leg, he made the imaginative leap to what it might do for breasts.

One Flat Thing, reproduced, used as the program's closer, is unabashedly based on a gimmick: It opens with fourteen dancers aggressively rushing forward, pushing before them large utilitarian tables that, arranged in an uncompromising grid, nearly fill the stage. They proceed to dance on top of them, underneath them, and in the stingy spaces left between them. The effect is that of humanity alive and kicking despite a world that has almost no space - space being to dancers as essential as air. Inevitably, the whole business is ridden with clichés: The tables become autopsy slabs, coffins, and the like; dancers not engaged at a given moment stand at the back of the space in a twilight of inaction, staring, expressionless, at the audience.

The piece is almost unwatchable, partly because, as with (N.N.N.N), its structure is ill-defined. Between the initial attack of the tables and their withdrawal, which closes the dance, the activity seems to occur almost at random, utterly even toned, threatening to go on forever, giving the viewer far too much time in which to ask, "What's this about?" Are we watching teenagers rampaging in their high school cafeteria or yet another one of those apocalyptic affairs art is prone to? Both maybe, and in both the spirit of Jerome Robbins seems not very far away.

Thinking about these works in retrospect as I was writing about them, I found more in them to admire than I did when I was watching them. Is this because a central aspect of Forsythe's choreography is conceptual rather than visceral? I must say I've always been leery of choreography that appeals more as idea than as dance.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary