Seeing Things: August 2003 Archives

Summer used to be the season of doldrums in the dance world. Not so anymore on the New York dance scene, though this is clearly contrary to nature. We need a rest before the jam-packed fall season. We need a laid back stretch of time in which we watch dancing, if at all, in the country, where—at Jacob’s Pillow, for instance—its intensity is relieved by greenery, picnics, desultory antiquing, indolence. But no. This summer, as in several summers past, there was unremitting action in town. And this year some of it came from choreographers ranking among the field’s hardest hitters, Mark Morris and Twyla Tharp. The city rebelled. What, after all, did you think caused the Big Darkness? Folks just didn’t want to see things for a while.

My own body rebelled, too, and I succumbed to what the doc called “a little summer flu.” Consulted after I’d spent two days in a semi-conscious state, unable even—oh horror of horrors—to read, let alone get myself up, dressed, downtown, and inside a theater, he prescribed the regulation antibiotic. The drug did its job, as drugs tend to do. I then had to recover from the drug. More than a week has gone by without my really noticing it.

Meanwhile, however, I’ve managed to do two things. Thing One: I’ve stocked the two databases (those items running down the right hand column of this page) under the rubric of TOBIAS ELSEWHERE. Now, should you be so inclined, you can catch up with the ESSAYS and REVIEWS I’ve been writing in that lovely land called “elsewhere” that are electronically accessible. Since the future of dance writing, increasingly shunned at print venues, clearly lies in the realm of electronic publication, I’ve been directing my writing life accordingly.

Thing Two: I’ve sorted out the mountains of press releases luring me (and perhaps you) to dance action that will take place locally between Labor Day and the winter solstice. My chief Go Sees through Hallowe’en: Ballett Frankfurt (choreography by William Forsythe), Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Opera House, Sept 30-Oct 4; U Theatre: "The Sound of Ocean," BAM Harvey, Oct 7-11; Suzanne Farrell Ballet, New Jersey Performing Arts Center, Oct 11, Brooklyn College, Oct 12 mat.; Merce Cunningham Dance Company, BAM Opera House, Oct 14-18; Ballet Nacional de Cuba, City Center, Oct 15-19; Susan Marshall & Company, BAM Harvey, Oct 21-25; Ronald K Brown/Evidence, Joyce, Oct 21-26; American Ballet Theatre, City Center, Oct 22-Nov 9; Reggie Wilson/Fist & Heel Performance Group, Joyce, Oct 22-Nov 1; Curt Haworth, Danspace, Oct 23-26; Ririe Woodbury Dance Company performing works by Alwin Nikolais, Joyce, Oct 28-Nov 2; Noche Flamenca, Lucille Lortel Theater, Nov 1-30 (previews Oct 29 & 30). More—much more—later.

For the middle two weeks in September, I’ll be in Copenhagen, where I plan to report on the Royal Danish Ballet, which will, conveniently, be offering a pair of programs during my stay that epitomize its split personality. The first is a “heritage” program featuring a new production of the incomparable Romantic-era choreographer August Bournonville’s La Sylphide. The staging has been entrusted to Nikolaj Hübbe, who, like many of Denmark’s spectacular male dancers, eagerly left his native land and company as soon as he could (he’s spent the major part of his performing career as a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet), but has, blessedly, never really severed his bond with the homeland. The second program will showcase the work of three balletic postmodernists. The Danes, who, despite the smallness of their numbers, have made uncanny achievements in several fields—dancing, literature, science, fine art, and, spectacularly, design—nourish a chronic inferiority complex. In dance, they’ve been yearning to get “with it” for the past seven decades, even if the illusion of contemporaneity required rejecting or despoiling the unique heritage that defines them. The company, looking ahead to 2005, when it will celebrate the 200th anniversary of Bournonville’s birth, is polishing up the master’s extant works, learning to love the old while forging ahead with the new.

After Copenhagen, I’ll begin reporting on the busy New York scene, where it looks as if the lights will be on full force.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in Tutu Revue.

Years and years ago, I asked Bill Carter -- a demi-caractère dancer with American Ballet Theatre, a flamenco dancer manqué, and one of the most soulful artists I've ever known -- if his vocation had already been evident in his childhood. "Oh, yes," he reminisced, "I was always dressing up and waving scarves around." Since that conversation, having raised a dancing child, who now has a dance-mad little daughter of her own, I've met with much evidence that there's a profound connection, especially in the very young, between dancing and costume.

Like dance, costume is a means of self-expression, which is nearly as essential to human life as air, nourishment, and sleep. Here is a young woman -- she signs herself "A Girl Graduate" -- writing to a newspaper in 1884: "I should like my dress to be a poem about myself, my persona, the outward and visible presentation of my individuality. And that particular mode and fabric and manner which I should choose might not at all recommend itself to my next-door neighbour. Indeed, I hope it would not. For the loveliest and most human thing about humanity is the infinity of its types and modes of manifestation."

Suzanne Farrell at age 8

While costume -- coupled, needless to say, with an artistic sensibility -- is a vehicle for realizing one's unique self, it is equally a powerful means of aspiring or pretending to be other (the secret self, or selves). Another poignantly young writer, Raymond Radiguet, dead at 20 after producing two novels charged with atmosphere, describes in "Le Bal du comte d'Orgel" a backstage visit paid by his exotic protagonists to a troupe of clowns that has captured a sophisticated public's fancy. "One went to their dressing room as one would to a dancer's. It was the scene of magnificent ruins, of objects shorn of their original significance that, in the hands of these clowns, took on a much higher meaning." The theatrical (and spiritual) alchemy of these circus artists is echoed later when the guests preparing for the costume ball of the novel's title seize the elements of their "disguises" from a jumble of discarded finery: "They saw in these rags the possibility of becoming what they would have wished to be." Children, of course, are singularly adept at the creative mutability Radiguet celebrates because the young psyche is still pliant, open to myriad identities.

Couple costume with dancing and you've added a Dionysian element. Costume envelops the body, but dancing goes further and animates it. A combination of the two allows the expression and metamorphosis of the personality to occur at fever pitch, vastly increasing the potency of the process. All cultures, no matter what their locale or time in human civilization, have known this and used the phenomenon in rites central to their existence. Children seem to know it instinctively.

Both dancing and costume also permit a vision of the self in a state closer to perfection than pedestrian life is likely to allow. They offer opportunities to appear stronger, more compelling, more complex and mysterious -- simply more interesting than one is ordinarily. Not least, costume is, like dancing, a way of being beautiful -- in one's own eyes and in the eyes of the audience that is always present, if only by implication, when we indulge in these charmed pursuits. Children, having the innocence and grace to pursue beauty without affectation, are particularly poignant when caught in the act.

The reader will forgive me, I hope, if I take the illustrations for my proposals close to hand. . . .

Not yet four, my granddaughter Lili, willowy and impassioned, dances in her living room wearing a costume for which the word ineffable might have been coined. Its bodice, of ivory crushed velvet, shapes itself to the tender curves of her torso. Its leghorn sleeves are fashioned from a mist of tulle above the elbow, glove-snug velours encasing the arm from elbow to wrist. Its skirt, the hem of which hovers between calf and ankle -- this is a sighing Romantic tutu, not one of those short, pert Classical affairs -- is confected of layered gauze that floats and clings, a cross between a silken web and drifting clouds. Scattered at random between the multiple skirts are tiny rosebuds. Not a single one is so bold as to appear on the surface, but leads a fugitive, half-hidden life as the child sets the gossamer matrix in motion with her ardent dancing.

Many a grown woman would be thrilled to be wed in such a dress. Lili herself, despite her extreme youth, is planning to be married -- to the person she'd like to spend the rest of her life with (as her mommy has defined the nature of a spouse). Lili's intended is Auntie Tonya who, as it happens, gave her this garment of dreams.

Meanwhile, Sara, Lili's very little sister, is determined to be included in the scene. Like many a "subsequent child," Sara wants to participate in whatever's going on, whether she understands it or not, whether or not she has acquired the requisite skills. A keen imitator, she has often seen Lili dancing with a collection of scarfs, many of which wrapped the birthday presents of her mother's childhood. They stand ready to hand in a carryall next to the CD player that provides music for the family's impromptu ballets. An eminently evocative one -- diaphanous, sapphire blue, and randomly studded with minuscule rhinestones -- suggests a set designer's version of a night sky. Another, a kind of lavender cobweb, has done exquisite service wafted around like a haze, a perfume, to indicate the presence of the Lilac Fairy. But Sara's favorite is a long striped Indian item, rich in robust, contrasting hues and thickly threaded with gold.

My daughter draws it out, slowly and seductively, from the motley tangle of fabric, asking, "Do you want your costume, Sara?" "Yes," the child says decidedly. "Is it this one?" "Yes," says Sara, adding an emphatic nod. She sits on the floor, patient and attentive, nude but for her diaper, as my daughter winds the fabric around her chest, knots it gently, leaving long fringed streamers trailing to either side, and turns on the music. Not yet in command of walking, Sara remains seated, bouncing avidly on her bottom, waving her plump arms in erratic shapes and rhythms, as Lili dances, my daughter dances, everyone passing through the room dances. Sara's spangled scarf swirls around her, making her look like an infant escapee from a Bakst design. Who knows what ballets this fledgling conceives? One thing, though, is clear: They cannot be danced in mufti.

Students of the School of American Ballet, NYC

Perhaps the most poetic costumes in the history of theater are those that fantasy-filled children create themselves for performances of their own devising. Certainly the best professional costumes for "faerie" ballets -- those based on "A Midsummer Night's Dream," for example -- retain the look of a soaring vision given ephemeral substance through improvisation from the materials at hand.

The opposite of such enchanting homemade raiment is the kiddie recital costume, the ghastliness of which, in taste and fabrication, should not be underestimated. By associating only with children who attend dance academies with scruples, you may avoid such exhibitions in real life, where they look not merely tawdry, but tragic -- at any rate a travesty of artistic values. Still, evidence of this dance-garb nadir shouts out from the ads that sustain most dance journals: the glitter, the spangles, the coarse nylon net protruding stiffly below sateen bodices, that surreal shade of pink that makes the color of well-masticated bubble gum seem subtle by comparison. A real-life encounter, however, occasionally provides a small miracle: Despite its vulgarity, this sorry finery is transmuted into a metaphor for beauty by the keen belief of the youngsters wearing it.

Students of Fantazia, a children's ballet school, Dubna, Russia

The costumes worn by committed dance students performing children's roles with a respectable ballet company are yet another matter. These garments, though they may still convince, even delight, the distant eyes of the audience, are often dilapidated, scarred by repeated repairs, stained with dust, makeup, rosin, and possibly tears. Being expensive, they are kept until they crumble or the ballet they outfit is dropped permanently from the repertory. The turnover in children doing a given role, however, is usually annual; the costume endures while a succession of faceless children outgrow it. The youngster who may be the twentieth or thirtieth body to inhabit one of these battered relics is not necessarily disillusioned. A certain glamour remains operative -- as if it had been sewn into the reinforced seams. Recalling the performances of her earliest years at the Maryinsky academy, the legendary ballerina Tamara Karsavina wrote in her memoir "Theatre Street," "the shabbiest costume was a glorious garment, and had the magic property of charming away all self-consciousness."

Student of the School of American Ballet, New York City

A seasoned costume can also speak evocatively to the susceptible apprentice of the venerable past of her chosen trade. It's the custom in some companies to label costumes with the name of their first wearer and to continue to identify them with that name long after the dancer has gone into retirement. My daughter, making her professional stage debut (if you will) as one of the Five Positions that open ABT's version of Harald Lander's "Études," wore a child-scaled tutu labeled "Isabella Fokine." The Positions are demonstrated by a quintet of female second and third graders. The role, which takes under two minutes to perform, goes like this: tendu into the assigned position, deep plié in same, rise, curtsy, step into sauté arabesque and run off into the wings. My daughter, being the neophyte in the group, was assigned to Second, the position in which you're least likely to waver in the plié or -- don't even think of it -- fall. But to wear the tutu first worn by Isabella Fokine, scion of the Fokine who changed forever the face of ballet -- now that was glory!

Here is Jimmy, just five, with a season's worth of much-desired creative movement cum elementary ballet lessons behind him. At the peak of the summer's heat, he's dancing in Lili's living room. He has the preternatural beauty often seen in Eurasian children and a body so perfectly proportioned it could serve as an anatomical paradigm of what the choosiest ballet academies audition for exhaustively. The arched feet alone are worthy of worship.

The children's mothers are soul sisters, now regrettably installed on opposite coasts. They've gathered for a rare visit with a cluster of other close friends from their student days, accompanied by an assortment of partners and offspring. The youngsters are still churning with energy, but the adults have succumbed to the languor induced by humidity and nostalgia. Jimmy rightly takes the assemblage to be a receptive audience, with luck even a malleable talent pool.

Clad in the cartoon-character briefs little boys affect these days, pink ballet slippers (the store in his town didn't have black and he couldn't wait), and a dime-store tiara, he springs about, wielding a plastic magic wand and delivering a simultaneous verbal explication of his antics. Like many a pioneer before him, he is choreographer and star performer at once. The smaller kids, wide-eyed with wonder, along with their bemused parents, are transfigured into aspects of his fantasy.

Wait! There's another element to Jimmy's costume, and it may be the key one. It looks like an over-the-edge hostess apron, its lush hues elaborated with shiny embroidery. Its function seems to be that of Prospero's mantle, the symbol of the wearer's spellbinding art.

"He's never without it," his mother comments, sotto voce.

The moment Jimmy drapes this makeshift cloak over his delicately sculpted shoulders and ties the apron strings to hold it in place, he is whatever he declares himself to be, all others present are who Jimmy declares them to be, and events evolve according to the dictates of Jimmy's imagination.

Jimmy's production -- a fluid improvisation that has obviously enjoyed previous incarnations -- is ambitious, to put it mildly. It has a narrative, fast-moving and fraught at every turn, part pop-culture adventure, part nineteenth-century storybook classics. It has sharply sketched characters, lots of them: good guys (and gals), bad guys (ditto), and supernatural creatures as well as animals. Typical of emergent-choreographer work, it has just about everything. And as all the witnesses are participants too, we players and public, one and the same, are caught up in its immediacy and fervor. Granted, only Jimmy is costumed, but the rest of us, it can safely be claimed, are wrapped in the aura of his fervent illusion.

Students of the Children's Ballet Theatre, Salt Lake City, Utah

I regret to report that since that vivid August afternoon, Jimmy has retired from dancing. By the time he turned seven, he could no longer bear being the lone boy in his ballet class. But surely other children destined to dance -- still mere toddlers, babes-in-arms, or as yet unborn -- children whose numbers are legion, will inherit his pink slippers (now grayed with use), his tiara, his magic wand, and his transforming mantle. The lure is irresistible.

© 2007 Tobi Tobias

This article originally appeared in Tutu Revue.

Every spring, America's two grandest classical ballet companies play a long annual season -- most of May and June -- opposite each other at Lincoln Center. American Ballet Theatre holds forth at the Metropolitan Opera House, while the New York City Ballet dances at the New York State Theater. The repertories of the two troupes are dazzling, in terms of both quantity and quality. NYCB is the repository of the work of George Balanchine, the giant of twentieth-century choreographers. ABT features opulent versions of nineteenth-century storybook classics like "Swan Lake" and latter-day imitations of the genre. Both companies boast additional treasures -- works by dance makers like Michael Fokine, Antony Tudor, Jerome Robbins, Twyla Tharp, and Mark Morris, who are sure candidates for the history books, as well as pieces by the most adept of the other contenders, the NYCB's Christopher Wheeldon standing just now at the head of that class.

Similarly, the dancing -- together, the troupes employ some 168 performers -- is of the very highest caliber. Each ensemble member can be said to represent hundreds of also-rans; he or she is, typically, the prize pupil deemed worthy of export to the mecca. Yet something essential is missing. Apart from a few senior artists whose powers have been waning for some time, neither NYCB nor ABT harbors anything you could genuinely call a ballerina. It may very well be that the species is nearly extinct.

Should we mourn it? I think so. "Ballet is woman," Balanchine declared, and despite sensational guys like Gaetano Vestris and his son Auguste, known 'way back when as "gods of the dance," and, subsequently, Vaslav Nijinsky, Erik Bruhn, Edward Villella, Rudolf Nureyev, Anthony Dowell and Mikhail Baryshnikov -- to say nothing of the cluster of kamikaze virtuosi currently exciting the ABT audience -- Balanchine had a point. It may take a female dancer, magnified exponentially until she seems more goddess than human, to make the proceedings on the classical-dance stage cohere and reverberate to the point of moving the viewer to ecstasy. (This sense of life amplified and glorified is what transforms otherwise reasonably normal folks into balletomanes -- the ballet-mad.) But what, exactly, is this creature we term a ballerina?

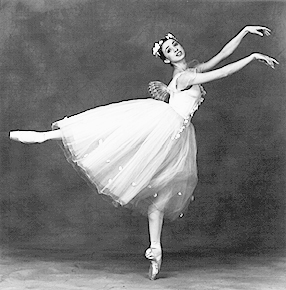

Marie Taglioni

One way to define her is to call to mind unforgettable examples of the breed. The ballerina as we conceive of her today can be said to have emerged in the Romantic era. In the 1830s the evolution of the soft dancing slipper to the reinforced pointe shoe, which permitted its wearer to perch on the very tip of her toes, helped to turn her into an otherworldly being, beyond the dullness of pedestrian existence. The enchanting engravings of the period exaggerated the look, so that the apparition the lady typically portrayed (the Sylphide, Giselle in her Wili guise) seemed poised on the business end of a needle, ready to be wafted into space by the merest breeze or admirer's sigh.

Fanny Elssler

The reigning idols of that period doubled their potency by emphasizing their contrasting temperaments. Marie Taglioni was chaste and ethereal, the "pagan" Fanny Elssler, a sexy fireball.

Anna Pavlova

Anna Pavlova epitomized the ideal of the ballerina in the early twentieth century. Like Balanchine a product of St. Petersburg's Kirov Ballet, Pavlova was an emblem of pure spirit -- now tragic, now possessed by a volatile joy. Her uncanny aptitude for seizing the audience's imagination (with the help of astute publicity) turned her into an icon. Even her death was mythologized. Legend has it that, gravely ill with pleurisy aggravated by her insistence on constant touring under grueling conditions, she died calling for her tutu so that she could give her next performance. What better way to seduce the public than immolating oneself upon the altar of art?

Margot Fonteyn

The ballerina of the mid-twentieth century -- the one who shaped the taste of devotees born before the second World War -- was the British Margot Fonteyn, whose career had an unusually extended life thanks to the charismatic partnership she formed with the young Nureyev upon his dramatic emigration from Russia to the West. Fonteyn was the paradigm of musicality, lyricism, purity of line in repose, harmony in motion. Her luminousness, which was warm rather than (like Pavlova's) above it all, was irresistible. Dance fans in the first third of the twentieth century worshipped Pavlova; their counterparts in the forties, fifties, and sixties loved Fonteyn.

Farrell and Balanchine

One more generation down the road, just at the vanishing point of the ballerina's dominance of the classical-dance stage, we have the incomparable adagio dancer Suzanne Farrell, Balanchine's last and probably most significant muse, a unique mix of the erotic and the sublime. Even these few examples suggest the diversity possible within the ballerina category; the shared quality, I'd venture, though cynics will ridicule the idea, is a gift for making dreams incarnate.

Galina Ulanova

Another way to describe the ballerina is to examine her attributes. They're a matter of both body and soul. Good-to-outstanding anatomy and technique can be considered prerequisites. (The preferred figure-type and the expected level of virtuosity have, of course, varied with the times.) Actually, some of the most memorable ballerinas have been deficient in one department or the other. Fonteyn, who happened to be a beauty, with huge, expressive eyes, and exquisitely proportioned to boot, was certainly no virtuoso. When she attempted showy feats like the thirty-two fouettés of the evil Black Swan, she zigzagged precariously towards the orchestra pit as the turns grew increasingly feeble. Her contemporary, the Bolshoi Ballet's incomparable Galina Ulanova, who with a few steps could convince you that the human spirit was a visible substance, had the face and build of a farmhand.

Generally speaking, the less tangible attributes turn out to be the most significant ones. A ballerina can act, where acting is called for. Far more interesting, however, is her ability to express or suggest feeling even in abstract ballets, lending them a subtext of implications that keeps them from looking like infernal machines. She has, too, an enormous vein of fantasy and the capacity, through it, to ignite the audience's imagination. Without stooping to the vulgarity of egoism -- ideally, a ballerina is modest -- she exercises a strong personal charisma. She fascinates you; literally, you can't take your eyes off her. A nascent ballerina will stand out in the most obscure reaches of the ensemble. And yet the ballerina is by no means a solo show; as the critic Edwin Denby once observed, she can "spread a radiance over the rest of the cast and the entire stage." She has mettle -- an abundance of physical and psychic energy and the daring to risk it continually. The supreme hazard -- allowing herself to be wholly open and vulnerable emotionally -- is one she eagerly tackles on a daily basis, before an audience of strangers. Above all, she's distinguished by a spiritual dimension that seems to be inborn. A ballerina may provide her public with visceral thrills of various sorts, but her special department is transcendence.

School of American Ballet students with the New York City Ballet. Photograph by Paul Kolnik. May not be reproduced without permission.

While companies with the clout of ABT and NYCB can, today, pick and choose from a huge number of physically gorgeous and technically spectacular dancers, they don't find (or nurture) many who possess the intangible ballerina qualities. Why? Because, I suspect, the type is rapidly vanishing from society at large. The Romantic mode of selfless aspiration, of dedication to an ideal, of single-minded commitment has simply gone out of style. Currently we live in a savagely pragmatic world, and this discourages the more ingenuous virtues. If we're guided by a vision, we know it's not cool to admit it. Imagine the hoots that, today, would greet a remark like Fonteyn's "I dance every performance as if it were going to be my last."

This attitude-shift in our culture is, to my mind, the primary reason for the disappearance of the ballerina, but secondary factors abound. Today's near-maniacal emphasis on technique also inhibits her development. The dance audience has become fixated on athletic prowess; you'd think it was watching the Olympics. Ironically, this avidity for multiple pirouettes in uncanny forms and aerial feats that seriously challenge the laws of gravity is self-defeating. There's a point - and we're edging close to it - beyond which the human body can't go; once most of a company's ensemble as well as its stars have reached that level of prowess, extravagant bravura loses its zest for the spectator. I've had the disconcerting experience of observing a company class that finished with nearly every woman in the studio whipping off those damned thirty-two fouettés, in unison. More is often less.

Sandra Brown and Johan Renvall

Needless to say, superficial feminist thought condemns the ballerina role for a woman. The traditional ballerina is perceived as fragile, passive, dependent on her male partner's support -- in other words, politically incorrect. As long as we misapply sociological values to art and scorn all cultural values but local ones, the sylphide model is not going to stage a comeback. Actually, those sylphides and swans are strong as longshoremen (longshorepersons?) and their partnered work is a paradigm of cooperation between the sexes, an extended miracle of cantilevering, balance, and timing. What's more, modern choreography for the ballerina makes her look empowered to a degree never dreamed of by the princesses and poetic wraiths depicted in nineteenth century classics. This evolution has been accompanied by a change in the nature of pointe work. In the nineteenth century its purpose was to make the woman appear delicate; today, both the dancer's technique and her toe shoes are far sturdier, and the effect can be Amazonian.

Present-day conditions -- some beyond human control, others capable of remedy if only there were more time, money, and purity of purpose -- limit the cultivation of ballerinas. Dance is a tough art; so much depends on circumstances. While a writer can work alone and in obscurity (think of Emily Dickinson), a complex and hard-to-come-by support system is required to develop a ballerina. She needs first-class choreography to teach her how to dance; classroom work alone will never do the job. And not only should she have a rich repertory available to her, she should, ideally, also have ballets created on her by a master who will instinctively tailor the dance to her anatomy, her skills, her temperament. He (classical-ballet choreographers are most often male; it's a Pygmalion-and-Galatea thing) will enhance her gifts, conceal her weak points, and, most important in promoting the performer's growth, unveil facets of her heretofore unrecognized. "He would reveal you to yourself," the French-bred NYCB star Violette Verdy liked to observe about Balanchine -- without whom Suzanne Farrell, Patricia McBride, and many another idiosyncratic talent might not even have had a significant career. Unfortunately, choreographers of worth are rare, and we are living through a particularly dry time, while the golden-oldie ballets are difficult to preserve in the style proper to them and still more difficult to retrieve if they've been shut away in storage for too long.

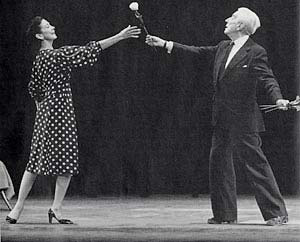

Fonteyn and Ashton. Photograph by Leslie E. Spatt. May not be reproduced without permission.

A potential ballerina also requires an artistic director who is perceptive about her needs and in a position to respond to them, someone who knows what can and should be done with the raw material she offers. Fonteyn was the most fortunate of beings; her choreographer was Frederick Ashton, who shaped the aesthetic of England's Royal Ballet; her artistic director was the founder of that company, Ninette de Valois, who commented, on her first glimpse of the fifteen-year-old then called Peggy Hookham, "We are just in time to save her feet," and only a few years later thrust her into leading roles in the classics. A ballerina also requires one-on-one coaching -- either from her choreographer or, in time-hallowed roles, from an astute and generous predecessor with a gift for instruction. This is a lot to ask. Like choreographers, artistic directors of genius are not abundant, and their creative freedom has been increasingly restricted by boards of directors fixated on the bottom line. In the coaching department, ABT does what it can, which isn't enough; NYCB has given short shrift to the possibility of coaching from the ballerinas Balanchine molded, Farrell foremost. All in all, the outlook is discouraging.

It's not that the scene lacks raw material. The female ensembles of both companies, it's commonly proposed, offer enough burgeoning talent to provide every company in this country with a ballerina. The NYCB has eagerly promoted the flowering of Maria Kowroski, a breathtaking adagio dancer who reminds veteran viewers of the young Farrell. Yet, despite her phenomenal gifts, Kowroski is usually at a loss in allegro work and, worse, at a loss when it comes to knowing who she is and what she's doing on stage. Too often her performances are vague and unfocused because she's hasn't yet learned how to inhabit her roles. Who will help her? Granted, she's only twenty-four, but she's already been with the company for six years, trusted with significant assignments from the very start. If she's worth cultivating, the process should be inextricably linked to every challenge given to her.

ABT's rising generation -- a cornucopia of talent -- is headed at the moment by the stunning Gillian Murphy, all regal authority and confident technique. So far, though -- I write just after her debut as Odette/Odile in "Swan Lake" -- she has failed to reveal the vein of fantasy and individual expression essential to a ballerina. Her demeanor is invariably grave, that handsome face frozen into a mask of retro glamour, the lush, big-boned body disciplined to a tautness that is understandable in an aspirant bent on perfection and success. Now that tight rein needs to be relaxed so that she can enter the human dimension in which the self is acknowledged, vulnerability is admitted, and artistry happens. Perhaps Murphy can manage this metamorphosis on her own; she appears to have a more self-sufficient temperament than Kowroski. The tragedy of a self-made dancer, though, is that she can be seen to be working in a vacuum.

Nina Ananiashvili

A ballerina is not an isolated phenomenon; she is the construct and the emblem of an artistic community. Perhaps it's for this reason that Nina Ananiashvili, one of the most lustrous dancers of our day, has been shortchanged in her ongoing relationship with ABT. The company seems to perceive her as belonging to a "foreign school" of dancing, and showcases her exquisitely in that way, but has not been able to integrate her as one of its own. While Ananiashvili's dual emphasis on plastique and impassioned theatrics does indeed recall her great Soviet-school predecessors, she is unusually "teachable," eager to absorb fresh takes on the classical tradition. The freest and most soulful performance I've seen her give was in Balanchine's "Mozartiana," staged and coached for Bolshoi dancers by Farrell.

Further depleting the ballerina ranks among our American-trained dancers is the dismaying increase in abortive careers witnessed in the last fifteen years or so. A corps member identified early on as ballerina material is likely to be plucked out of the ensemble too soon and overburdened with responsibility instead of being allowed -- and helped -- to mature gradually. Today's wunderkind is too often tomorrow's burnt-out case. The NYCB's lovely Miranda Weese, who seemed every inch a ballerina-in-the-making, has gone into a baffling eclipse, just as, a decade earlier, ABT's Amanda McKerrow, a crystalline dancer with the touching air of a princess in exile began to fade from the scene without ever realizing her full potential. Yes, injuries, illness, and failures of confidence play their part in such sad trajectories, but one wonders if the salvage rate couldn't be bettered.

The hardiest survivors of forced development, in which vicious competition plays its inevitable part, sometimes turn tough and calculating, able to foster their prominence but not serve their art. Others -- I think of ABT's Paloma Herrera -- are corrupted by circumstances into becoming caricatures of their most saleable qualities. No one seems to mourn what has been lost; the prevailing mood is eagerness for the next potential star. Today's audience has a ravenous appetite for novelty -- this is a disease that pervades our entire culture -- and so the turnover is swift. Like so many commodities, the newest discoveries efface previous ones before the older ones have really had their day. Besides being wasteful and cruel, this frenetic turnover works dead against the best interests of an art bound by its very nature to tradition.

The only way, perhaps, to live with these difficult truths is to admit that an era is irrevocably over. The world of classical dancing is reconstructing itself according to radically different conditions and values. Ballet is very likely to continue and flourish without ballerinas as we once knew them, and, in its new guise, will no doubt find a responsive audience -- probably a young and inexperienced one. The seasoned viewer who is unable or unwilling to journey into this cooler and harsher domain may have to rest content with memories.

© 2007 Tobi Tobias

SEEING THINGS invited dancers and dance aficionados (as well as mere pedestrians) to respond to this question: Some would say that dancing is the cruelest profession, all but guaranteeing grueling work, physical pain, poverty, and heartbreak. Yet the field has always been rich in aspirants willing to dedicate their lives to the art. Why?

The first group of responses was posted July 28th. Here is a second group.

METTE-IDA KIRK writes:

Dance and music are among the most beautiful gifts humanity has been given. And when the dancer experiences what it means to phrase a movement, what possibilities of expression it contains, she will focus passionately on bringing the choreography to life. Yes, pain, obstacles, and endless work are a part of this process, but when it succeeds, the reward is catharsis. (Translated from the Danish by TT)

MAIDA WITHERS writes:

Why dedicate one's life to dance and encourage others (company members and students) to do the same? Because-

. . . dance offers a high unequalled by any other experience I have known.

. . . it is the most immediate way to access every fiber of our being.

. . . the wanderer in me wants to see the world, and dancing my way around the world is a passport to living.

. . . it gives me a forum in which I can encounter others.

. . . making dances and performing dances documents all aspects of our lives, charts our past, and predicts our future.

. . . the music is there.

. . . all these costumes need someone to make them work properly.

. . . dancing is what I know how to do.

. . . my heart keeps making me do it.

DANA TAI SOON BURGESS writes:

Why dance? Because I realize that nothing else in the world can satisfy my need to express inner perspectives, hidden longings, and repressed desires. Creating dances is my way of presenting my thoughts three-dimensionally. Because dance is a field in which mentorship continues to thrive. Watching information move from dancer to dancer, from generation to generation, I feel I'm part of a larger tradition. This process quiets my mind and answers questions about the passage of time and the ephemeral nature of life. Because in a dance studio I can be totally present in the moment, with a focused mind and body. I can't manage that anywhere else, no matter how often I try to meditate, burn incense sticks, or listen to tapes of the ocean! There is something fundamental about the process of dance that allows me to tap into the collective unconscious, to find calm in moments of calamity.

A last word, from MARTHA GRAHAM:

I am a dancer. I believe that we learn by practice. Whether it means to learn to dance by practicing dancing or to learn to live by practicing living, the principles are the same. In each it is the performance of a dedicated precise set of acts, physical or intellectual, from which comes shape of achievement, a sense of one's being, a satisfaction of spirit. One becomes in some area an athlete of God.

Mark Morris Dance Group, Mostly Mozart Festival / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / August 4-6, 2003

Adding dance to Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival for the second year in a row, the Mark Morris Dance Group performed four works from its repertory—nothing new, but most of it pretty damned wonderful.

Of the two chamber-scaled pieces presented, the 1992 “Bedtime,” set to Schubert songs, can’t possibly be called minor. Its first section, a lullaby, is so simple in its material, so understated in its means, and so poignant in its effect, it alone might serve as proof of Morris’s genius. A tall elegant woman in golden pajamas—call her the goddess of sleep—keeps vigil over three quiet recumbent bodies at the front edge of the stage, soothing their repose, you assume, perhaps animating their good dreams. Eventually, from the twilight recesses of the space, she draws another three figures, one to watch over each of the sleepers, to serve in her place as their caretakers and companions. That’s it. The message? The one a mother implicitly sends to her child: I cannot always be here to take care of you, but I promise you that someone always will. This lie—the mother’s need to tell it, the child’s need to hear it—and the fact that it can be rendered through dancing and music as the universal wish it represents, make you cry.

When Morris himself danced Cupid, enabling a rural swain and his lass, in the 1993 “A Spell,” I thought the piece (set to songs by the Renaissance madrigalist John Wilson) a mere bagatelle. Now that the role has been handed on and its outrageous archness—there goes Mark again!—toned down, I see that far more is happening here. After the period of romance and lust, flirting and fucking in the country lanes frequented by Shakespearean peasantry, the lovers become entirely postmodern—us, in fact. And the woman, tragically, wants far more than her baffled partner can offer, more than she can, herself, put a name to. Long before the dance ends, Cupid has vanished.Created in 1981 and revised in 1984, “Gloria” (named for its Vivaldi score) was—and remains—a major triumph. Morris reveals in it a key aspect of his character—profound empathy with the human condition. We are, by virtue of being human, maimed and doomed, he suggests to us. And, he goes on, we are, also by virtue of being human, capable of salvation—or, more simply, unreasoning aspiration, hope, and joy. “Gloria”’s ten dancers stagger, fall, and continue relentlessly in their path, crawling awkwardly and painfully, in a jagged rhythm. Elsewhere they run and leap exultantly, as if miraculously restored, by stubborn devotion, to the fluency of physical and spiritual well-being. The choreography operates by responding to the structures in the music with action that can be described in simple, concrete terms. It dictates no emotion. Yet it elicits deep feeling from the spectator because of Morris’s great gift for knowing, about movement and gesture, what, how much, and when.

“V” (to Schumann’s Quintet in E-flat major for Piano and Strings), was clearly the “big” work on the program—the spectacular item in terms of scale and punch, meant to assure the general audience it was getting its money’s worth. Ever since its premiere in 2001, though, I’ve felt that I’m in a minority of one among Morris's admirers. Well, two, the other being my companion at the theater last night. Most Morris enthusiasts claim that “V” equals—even tops—his masterworks of the previous two decades. Not to my eyes.

After some four viewings, I’m more convinced than ever that “V” doesn’t earn the ecstasy it lays claim to. All those Amazonian leaps, arms flung skyward. All those onslaughts in V-shaped phalanxes. All those pairings off into full body hugs (“Oh, God, I’m so glad to see you. I was sure you were dead.” The dance was “Dedicated to the City of New York” in the wake of 9/11). “V” panders to its audience with scads of meet-and-greet stuff, the dancers advancing straight-on, practically into the public’s lap, arms open wide in a proffered embrace. Worse still, the piece has only two modes—grim and elated; it ticks as unremittingly as a metronome between them. The varied emotional texture of “Gloria,” with which it shares its themes, puts it to shame. What’s more, as Morris’s detractors claim—unjustifiably, I think, about everything he does—the choreography seems to be little more than music visualization. Each time I see “V,” it seems more specious.

“Ah, but—“ interjects my companion, who was equally unimpressed by the choreography. “But what?” I challenge. “The dancers.” There she has me. About these glorious creatures—each unique—I have no reservations. More about them, I hope, another time.© 2003 Tobi Tobias

Sitelines

AJ Ads

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

360° Dance Company at DTW offers two socially relevant revivals, Jane Dudley’s solo “Time Is Money” (1932) and Mary Anthony’s “Devil in Massachusetts” (1952) as well as the World Premier of Artistic Director, Martin Lofsnes' "6-1".

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary