American Ballet Theatre / City Center, NYC / November 8-13, 2011

This season’s gala-event costumes for women of a certain income emphasize cascading ruffles in weak-willed pastels or glowing jewel tones. The men continue to sport black-tie mufti with almost no rakish variation on the theme. Expense is evident, as is the eternal question of hoi polloi concerning the gowns with obviously crushable skirts, How does she sit down in it?

Despite the War: American Ballet Theatre’s Luciana Paris in Paul Taylor’s Company B

Photo: Gene Schiavone

This fashion report comes from the opening night of American Ballet Theatre’s week-long fall season at the handsomely renovated City Center–now gorgeous and comfortable beyond belief. The repertory for the week eschewed the company’s multi-act classics (Swan Lake, now in warped form, Giselle, et al.) and wannabe classics (Neumeier’s Lady of the Camellias, Kudelka’s Cinderella) that ABT offers in its long spring seasons at the Metropolitan Opera House. Each program in the City Center run purveyed three or four ballets that owe more to modern dance (Paul Taylor’s), postmodern dance (Merce Cunningham’s, Twyla Tharp’s), and ballet being catapulted into the future (Alexei Ratmansky’s), than to the strict conventions of classical ballet.

Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: Kristi Boone in Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

The high point of the opening night show was, incontestably, Twyla Tharp’s In The Upper Room. Created in 1986 for Tharp’s own company and set on ABT in 1988 the ballet is a powerhouse; it starts at the top of the scale energy-wise and escalates from there. Philip Glass’s driving score is a full partner in the dancers’ trip to Paradise, assuming that’s what the “upper room” indicates.

Upper Room divides its cast into two different sects: those shod in sneakers (affectionately called the Stompers) and those who favor classical dance footgear, which means pointe shoes for the ladies. The two camps eventually merge, as they have in the course of Tharp’s career.

Tharp’s relentless choreography displays dozens of terrific things you can do when you mate academic dancing with Tharp’s personal style, a brew of both classical and modern dance, jazz, pedestrian gesture, and myriad other fascinating ways of moving that she fixed on in her childhood from an eclectic set of lessons and since then through her magpie instinct. Boxing, just for starters.

Upper Room is perfect proof of the fact that Tharp is a demon of patterning. You can feel her brain ticking away as one design succeeds another. Her choreography offers a kaleidoscope of moving bodies arranged in space, each image utterly clear and then gone, giving way to the next, just seconds after you’ve taken in the preceding one.

The overall pace of the dance seems furious, the action mounting in fervor. The speed makes obvious the risks the dancers are often taking–seemingly without fear but, rather, savoring the reward of attempting the near-impossible and achieving it. It’s quite possible that in this piece Tharp is telling us this is one of the main factors that make a dancer dance.

Costumes and lighting are not relegated to supporting roles in this production; they’re striking essentials. Norma Kamali designed a wardrobe of prison-striped black and white pajama-like outfits, accented by a blinding red. (The women’s gleaming red pointe shoes (worn over red socks) is a terrific latter-day sequel to the demonic footgear Moira Shearer wore in the best dance film ever made.) As the dance progresses, the cast gradually sheds the coveralls to reveal more and more carmine underneath.

The lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton astonished the audience when Upper Room was first performed. She filled the upstage area with a drifting fog from which the dancers emerged–as if by magic–and into which they disappeared. At the City Center performances, which Tipton did not supervise, the entire stage was suffused with smoke that never moved and functioned as a pale gray scrim that never lifted, thus diminishing some of the action.

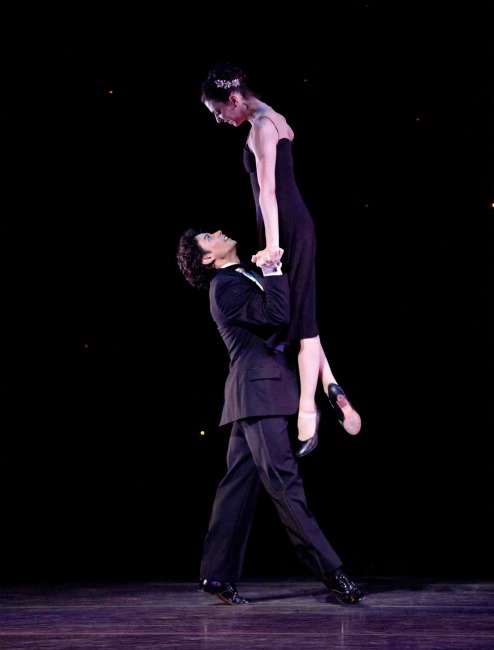

Starry Night: Herman Cornejo and Paris in Tharp’s Sinatra Suite

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Herman Cornejo’s return to performing after a long recuperation from injury was reason enough to be happy and excited by the evening’s performance of Tharp’s Sinatra Suite. Cornejo is a unique dancer–an extraordinary technician who, refusing to be typed by his scrappy-kid-brother looks, has extended his abilities to danseur noble roles, modern dance roles, you name it. At his best he’s an artist who infuses everything he does with life.

Cornejo wasn’t at his best in this duet on opening night, He was having obvious trouble with the lifts, and his partner, Luciana Paris, was of no help to him, apparently having problems of her own. He also tended to separate elements in the dancing that should be fused. He called undue attention to feats demanding classical ballet prowess because he executed them so immaculately, meanwhile failing to articulate the jazzy, gymnastic, and casual elements that are essential to Tharp’s signature style.

He was encouragingly better in the closing number, a solo to “One for My Baby (and One More for the Road).” There, the lyrics conjure up a guy who has been through it all telling his sad story to the bartender in a seedy dive about to close for the night. Here, too, Cornejo danced with too much emphasis on the classical bits and too much self-conscious acting, but also with hints that he was beginning to set matters right. The important thing is that he’s back on stage. He’s not just one of ABT’s great stars; he’s indispensable.

Sinatra Suite got its ideal cast at a later performance when Paloma Herrera and Marcelo Gomes took the leading roles–they’re both innately sexy dancers and have reciprocally crackerjack timing. The richness they brought to the succession of songs that runs from dewy-eyed romance to the inevitable break-up went so far as to hint toward the end that it’s the woman, not the man, claiming “I did it my way.” Being a generous performer as well as a singular one, Gomes let Herrera go for it.

As for the choreography, not only is it inventive, it’s also vibrantly expressive about the shifting moods of love. (In the Upper Room has only one mood: driving on Ecstasy.) To my mind, though, the ballet was even better in its original incarnation, the 1982 Nine Sinatra Songs–more thrilling, more sensuous, occasionally even amusing (remember the bumbling young sweethearts of “Somethin’ Stupid”?). Using more songs, that piece involved several couples and was originally danced by the singular members of Tharp’s own company, back in simpler times, when the choreographer had her own company.

Five in a Row: A line-up of ABT’s male dancers in Demis Volpi’s Private Light

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

The big curiosity of the evening was the premiere of Private Light by Demis Volpi, who is a mere 25 years old. The Argentinean-born dancer-choreographer trained in his homeland, then in Canada, and finally came under the wing of the Stuttgart Ballet, joining the company in 2004. He began to choreograph in 2006 and has enjoyed the support of Stuttgart’s Noverre Society, which has aided several emerging choreographers who went on to international fame. He has since gathered much attention and much praise, but I can’t join in the applause.

Generous apologists for Volpi are bound to say: He is a beginner and he will learn. But anyone examining the careers of the western world’s choreographic geniuses (Balanchine, Graham, Ashton, and Tudor leap to mind) will see that they refined their craft over the years–choosing, according to their own inclinations, whose inventions to imitate, steal from, or build upon–but that their artistry and unique imagination were unmistakably in them from the beginning.

Clearly, Volpi has learned the set rules of his trade. For example: Select a movement theme, state it early on, then thread it throughout the piece, giving it a few exact repeats but even more variations. The trouble with Volpi is that he hasn’t absorbed such rules organically; they remain merely intellectual propositions that never become visceral or vivid–or make any obvious point.

In Private Light Volpi fixates on the idea of the line-up, the kind in which the police present a prospective witness for the prosecution with a handful of people (among them the suspected criminal) who resemble one another. They stand under bright light, their bodies evenly spaced in a horizontal line. The Volpi version uses five male-female couples and insists, throughout the piece, on the rule of five, a tactic that makes the ballet feel increasingly tedious and contrived.

A major feature of the piece is The Endless Kiss–heavy mouth-to-mouth smooching. Its repetition is neither interesting nor (as I assume the choreographer meant it to be) funny. Another big deal has one of the men (Joseph Gorak) neatly executing excerpts from a ballet barre without a barre to support him, as a little horde of his colleagues are periodically revealed to be watching him. The solo is a feat, to be sure, but a dry one, and the point of it remains murky.

The central segment of Private Light is a duet for Simone Messmer (who creates a different persona for every one of her ABT roles) and Cory Stearns. Messmer first appears alone, doing one capricious thing after another, like a girlchild who’s been brought up under the free-to-be system. When her partner arrives–signaling the beginning of her adulthood–her shenanigans become grotesque enough for the spectator to wonder if she’s being abused. She keeps collapsing, a victim in his arms. Am I just imaging this or is Europe’s contemporary ballet more tolerant of nasty behavior towards women than we are in America?

The most agreeable element of Private Light was its accompaniment–selections ranging from folk-style music to classical pieces by Albéniz and Villa-Lobos, enticingly played at the edge of the stage by guitarist Christian Smith.

Ménage à Trois: Alexei Agoudine, Xiomara Reyes, and Grant DeLong in The Garden of Villandry, co-choreographed by Martha Clarke, Robby Barnett, and Felix Blaska

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Set to Schubert’s beguiling Trio No. 1 in B Flat, The Garden of Villandry, co-choreographed by Martha Clarke, Robby Barnett, and Felix Blaska, had its world premiere with the adventurous Crowsnest group in 1979 and its company premiere with ABT in 1988. It’s one of those bagatelles that lasts a surprisingly long time.

Villandry, as the program might usefully have mentioned, is one of the16th-century châteaux on the Loire (small castles, such as fairy tales depict), best known for its elaborate formal gardens. The site, painstakingly refurbished and scrupulously tended, is open to tourists whose reaction, in their myriad tongues, is invariably “lovely” or “amazing.”

With the musicians in an upstage corner, a trio in Edwardian dress dances the subtle–and mercurial–relationships among two gentlemen and the lady they both desire. The dancers on this occasion were the perennially lovely Julie Kent; Roman Zhurbin, a sturdily built and quietly resourceful character dancer; and Julio Bragado-Young, who looks like a stock character–the pale, undernourished young tutor of yore who has a few wealthy children under his care and a head full of impossible dreams.

The dancing is a detailed study of the myriad ways in which three bodies can join and intertwine and (very rarely, never creating too much distance between them) separate. Hands touch and withdraw. Gentle kisses, mostly a brush of the lips on a cheek, are given and accepted. Secrets are whispered behind a cupped hand held to the sharer’s ear. The lady lets her head fall on one suitor’s shoulder and then, playing fair, on the other’s. She is swung into the air by both, her long white skirt flying with her–a shroud of chastity, perhaps. She rejoices in the admiration her courtiers give her and sweetly, always tactfully, returns the pleasure.

Imagine, if you’re a member of the so-called gentler sex, the most romantic and refined of your female friends actually admitting she wanted to live such a life. “Oh,” you might well scoff, “it’s like a perfume ad.” But then who are you to judge? You don’t wear perfume.

As the ballet went on, I expected some crisis to the situation that had been so artfully and meticulously presented, some climactic scene, some horror, perhaps, or at least some melodrama. (Throughout a long and fruitful career, Clarke has regularly revealed her penchant for eerie, alarming scenarios.) Even when I decided that the participants in the trio probably don’t crave a solution to their problem, that they no doubt find it exquisitely romantic, I still remained ignorant of the tone the piece was taking toward the whole business. One contextualizing clue: the ballet begins and closes with the three dancers staring reproachfully at the audience as if we lookers-on were voyeurs.

Ménages à Deux: Paloma Herrera and Eric Tamm in Merce Cunningham’s Duets

Photo: Gene Schiavone

ABT’s acquisition of Merce Cunningham’s 1980 Duets, one of the late choreographer’s most accessible works, may be a forecast of how that repertory will fare when the Cunningham company disbands at the end of this year, as part of Cunningham’s plans for his works’ life after his own death. His dances will be released to other qualified troupes, with a former Cunningham performer appointed to set and coach the work.

I can’t imagine Cunningham’s dances being in better hands than those of Patricia Lent, who transmitted Duets to a pair of ABT casts. In a particularly rewarding Works & Process program at the Guggenheim Museum in October, Lent worked with Isabella Boylston and Craig Salstein, making sparse, concise corrections and suggestions in the most even voice imaginable, never inflecting the information with her personality. She might have been a latter-day guru. Everything she said made good sound sense.

In performance the plainspoken yet mysterious choreography suggested a realm of dancing almost alien to ABT’s nonetheless eclectic repertory. It was only natural that many of classical ballet’s conventions, deliberately abandoned by Cunningham, automatically surfaced: dancing to the audience; dancing that ended in freeze-frame images; dancing that emphasized the brilliance of a certain step or phrase. But most of the performers seemed to respect the unfamiliar horizons and want to explore them, which is a good sign.

Fighting Depression: A scene from ABT’s production of Paul Taylor’s Black Tuesday

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Paul Taylor’s dances have been well absorbed by ABT’s dancers, as was evident in the week’s performances of the 1991 Company B and Black Tuesday, created in 2001. In a method Taylor has worked out for himself, both pieces were first done by classical companies and then quickly absorbed back into the Taylor company’s repertoire, where they seemed to find their most genuine interpretations. Still, Taylor has long claimed that he has no problem with having his choreography performed with a classical accent. Moreover, ABT’s version of the pieces I’ve named have, a decade or two after they were choreographed, taken on an ebullient life. The reason? Increasing familiarity with the Taylor way of moving and the ability of the upcoming generation of classical dancers to excel in a wide range of styles.

Ballet Blanc: Reyes and Cornejo in Alexei Ratmansky’s Seven Sonatas

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Alexei Ratmansky’s 2009 Seven Sonatas, set to seven of Scarlatti’s Keyboard Sonatas (played onstage by Barbara Bilach), is a delectable choreographic feast. I thought it marvelous when I first saw it, but it’s even more gratifying now, having grown richer through repeated performance–and through my own better appreciation of it after repeated viewings.

As usual, Ratmansky is rigorous here, offering a cornucopia of invention without leaving the context in which he’s working. And as usual his choreography is packed with evidence that he has learned from the masters he honors. He even pays them overt homage; I spotted brief quotes from Fokine, Bournonville, and Balanchine, among others. And of course there are little jokes–amusements, rather–along the way, which seem to reveal the sheer pleasure that dance gives him.

Three couples constitute the cast of Seven Sonatas, so it might be called a chamber ballet. It might also be termed a ballet blanc because it’s costumed in white–for the men as well as the women, actually–and because it refers to the Romantic vein of purity and fleet, weightless execution. It also seems to be plotless, but Ratmansky is an irrepressible creator of subtexts. At one of the two performances of the piece that I saw in ABT’s crammed week at City Center, I was convinced that the ballet was revising the story of Bournonville’s La Sylphide: Young man captures the otherworldly sylphide and–guess what?–they proceed to live a charmed life, full of laughter. Ratmansky danced and choreographed for the Royal Danish Ballet for several years, so he must know the Bournonville version by heart.

ABT’s week at City Center was a terrific stylistic challenge to its dancers, a showcase for performers exiled to lesser roles in the blockbuster multi-act works that prevail in the company’s long spring season at the Met, and a way to attract an audience that isn’t mired in old conventions. Is it possible that the company’s two profiles can be reconciled? If that seems impractical, how about two weeks at City Center next year?

© 2011 Tobi Tobias