Jonathan Burrows & Matteo Fargion / Danspace Project, NYC / November 3-5, 2011

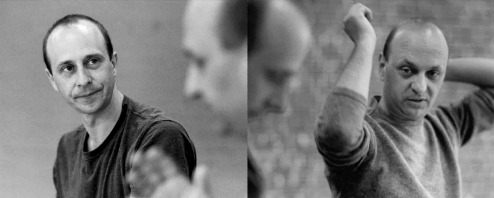

Shadowplay: Jonathan Burrows (l.) and Matteo Fargion (r.) in their Both Sitting Duet

Photo: Herman Sirgeloos

When the presumably odd couple Jonathan Burrows (dancer and choreographer) and Matteo Fargion (musician and composer) played the Kitchen back in 2004 in their Both Sitting Duet I titled my review (lots of description, some analysis, intimations of enchantment) “Less Is More.” Seven years later, they’re back in New York for three performances at Danspace Project, for which they may have been thinking that less was not quite enough. Opening night was essentially a double-header: their first success here was preceded by Cheap Lecture and The Cow Piece, two works, made in 2009, that New York hadn’t seen yet.

Before I get to the more recent pieces, I’m reproducing my 2004 report for ArtsJournal because it sums up what I saw–and still see–in Both Sitting Duet.

IS LESS MORE?

Jonathan Burrows/Matteo Fargion / The Kitchen, NYC / March 11-13, 2004

Is less more? Answer: Yes, when we’re talking about Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion’s Both Sitting Duet. Performing the 45-minute piece they invented, the two guys sit on battered regulation-issue wooden chairs smack in the middle of a bare, black-box stage space. The chairs are congenially angled toward each other, as if set up for conversation. The men, who have a certain physical resemblance, are early middle-agers with compact bodies and keen, worn faces. Their costume–no-nonsense jeans, nondescript shirts and shoes–is the epitome of ordinary. You’d pass them on any urban street without a second look.

Each man has, at his feet, a notebook scrawled with words and symbols that he eyeballs regularly, as a musician does his score. Fargion is a musician; Burrows, a ballet-trained dancer and choreographer. Shortly after they’ve launched into their . . . tour de force of arm and hand jive, you can tell from their movement–even though they’re executing the same gestures in unison, in canon, or as rapid-fire Q & A–who comes from which art. Burrows’s execution is the more sharply focused, projected toward a presumed spectator. Fargion’s, with its softer edge, seems inner-directed, has a slightly more subtle rhythm. Burrows powers his arms from his gut, while Fargion operates mainly from the shoulder, his midsection lax.

Here’s what they do: shake their hands wildly in front of their chests, so their fingers look like sparklers; use one hand to count the fingers of the other with a child’s deliberation, as if the answer might be in doubt; stroke their palms along their trousered thighs; palpate the floor with their fingertips; curl their fingers into vivid mudras that yield no explicit meaning; extend their arms in semaphore signals or (Burrows alone, while Fargion softly claps out a tempo) classical ports de bras.

A couple of times they stand up for a few seconds, even go so far as to turn in place, repeating a raucous cry; once they shift the position of their chairs so that one lies in the other’s shadow. Such departures from what they’ve set up as the parameters of the piece have the impact of high drama–violent and haunting.

Most of the time they remain seated, their movement largely confined to their arms and hands, torso and head just going along for the ride. They make a lot of eye contact, though, and run through a gamut of facial expressions that suggest a ping-pong exchange of ideas and a brotherly relationship that’s both challenging and complicit.

Will you believe me if I tell you this wasn’t tedious? Far from it. Just the opposite. The more things remained, so to speak, the same–one man’s move copied by the other, a single gesture repeated again and again by both–the more fascinating the whole business became. The secret–an open one, to be sure–lies foremost in the small, canny variations in rhythm with which the performers inflect each unit of basic material. Example: Delivering a rapid three-gesture phrase for one hand, the pair begins by working in unison, then lets its individual articulations go slightly out of synch in a loop that keeps returning to the original unison and departing from it again. It’s like the hypnotic action of windshield wipers with a slight glitch in their mechanism.

Another part of the secret: The repertory of moves is adeptly structured, alternating between the small and the large, the fierce and the delicate, the agitated and the serene, the sounded (slaps, claps, pats, occasional stomps or monosyllabic cries) and the silent. In the silence–the piece has no conventional musical accompaniment, and the audience was rapt–the very scratching of a reporter’s pen on her notepad seems an intrusion.

And then, rewarding one’s alertness, there’s the message (you might even call it the moral) of the piece: A close focus on replication paradoxically allows differences to emerge, minute states of otherness growing immense in scale or suggestive power.

Here’s what Both Sitting Duet made me think of: Pairs of Parisian intellectuals, sitting in cafes, exchanging abstruse ideas for the fun of it. My uncles hunched over a card table, playing infinite games of pinochle at my grandmother’s house, every Sunday afternoon of my childhood. Deft practitioners of American Sign. Obsessive-compulsives. Language teachers demonstrating the gestures that accompany voluble Italian. Merce Cunningham.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

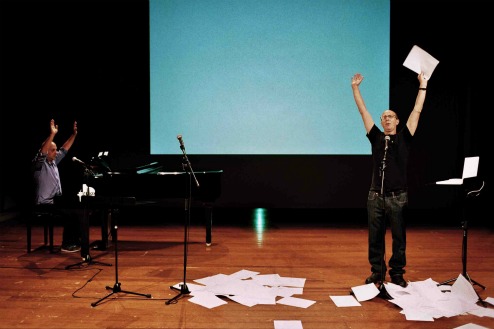

Two’s Company: Burrows (l.) and Fargion (r.)

Photo: Alastair Muir

Now, what about Cheap Lecture and The Cow Piece? Both are dazzling, and they belong together. The first makes its point largely through words; the second, through absurdist deeds. Both ramp up Burrows’ and Fargion’s particular gift–articulation and offbeat timing in spoken language and body percussion–to such a virtuosic degree that a first-time onlooker’s head starts to reel. I, for one, felt I was taking in only part of what was actually going on. I’d jump at the chance to see both pieces again, right now. Best of all, while the more recent pieces are soundly rooted in the couple’s earlier work, they also move it along to more complex developments, refining and advancing their unconventional aesthetic.

Cheap Lecture is a loving mockery of sessions purporting to convey information–even wisdom–by a pair of professorial types. You’ve sat before them, puzzled or benumbed, in college or the halls of adult education. (Granted, this pair is dressed like handymen, but that costume is just these artists’ trademark.) Each fellow, standing, speaks into his own standing mike, but the two thread their utterances into their partner’s as if to represent a single person. Silences, little and large, make for the duo’s off-beat timing, and their use of repetition owes much to Gertrude Stein. Each guy holds a sheaf of paper that is supposedly the script of his talk. Page by page, he drops it onto the floor when he finishes making one of his pointed/pointless points. Behind the speakers is a large screen onto which are projected the key words and phrases of their rant; these might be the notes taken by a dutiful listener, pathetically intent upon enlightenment. Be assured, though, that the B&F tone is neither bitter nor supercilious. Life is absurd, they’re telling us, and we’re all in it together.

Information Please: Fargion (l.) and Burrows (r.) in their Cheap Lecture

Photo: Herman Sorgeloos

The Cow Piece uses the same setting–but to another purpose. Burrows and Fargion stand behind a pair of laboratory-style tables, each of which has become home to a mini-herd of a half-dozen three-inch plaster or plastic cows. On an undercoat of white, half of them are spotted black; half, sienna. The men are their irresponsible shepherds, given to the intermittent playing of invitations to peasant-style dancing–on a harmonica, a mandolin, and (my erudite guest informs me) a miniature harmonium.

The men arrange and rearrange their cows obsessively and count them again and again like uncertain, if loving, parents. Farjeon even names his–Italian names, like Bella and Lavinia, that refer to his ancestry. As the pace of these doings and the energy put into them accelerate, the men–like very young children whose playing has gotten out of hand–escalate into gleeful cruelty to their cattle, knocking them down and, clever devils, hanging them on minuscule ropes made of string. Throughout the piece, the narrative is accompanied by all the iterations, gestures, and skewed timing typical of the makers’ style. The crazy antics and even wilder joy are horrifying and amusing at the same time.

Something I continue to find amazing about Burrows and Fargion’s work is that many of its viewers think at first that they’ve stumbled upon little-known talent–you know, just by accident. No such chance. The duo has performed its repertoire internationally, consistently intriguing its audience, and has been officially commended with honors such as a New York Dance and Performance Award (a “Bessie”) and high-end commissions (for Burrows) from the likes of William Forsythe’s Ballet Frankfurt and Sylvie Guillem. At first glance, the pieces don’t seem to have any hidden ambitions but rather to be like something you yourself (or, more likely, a clever child) could fashion with one of those kits of 1001 click-together parts. The simplicity of means in Burrows and Fargion’s work and the sheer fun that pervades it seduce you into loving it. All the while it’s inexorably revealing its genius.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias