Duŝan Týnek Dance Theatre / Tribeca PAC, NYC / October 27-29; November 3-5, 2011

Duŝan Týnek Dance Theatre

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Seeing the Dušan Týnek Dance Theatre, recently at Tribeca PAC, in the second of the two programs it offered, made me wonder why the standing of its marvelous choreographer hasn’t graduated from “promising” to top-of-the-line. If he were working for a big institutionalized company like ABT or New York City Ballet, he might blow contenders like Brian Reeder and even Benjamin Millepied off the map.

Czechoslovakian-born, Týnek emigrated to train and dance in New York. His mentors include Aileen Pasloff, Merce Cunningham, and Lucinda Childs. He formed his own company, Dušan Týnek Dance Theatre, in 2002. From my first sight of his work, I was hooked on what he was doing.

“Ambitious beyond its power to deliver, the piece is filled with vision, charm, and wit,” I wrote about his Pilot’s Dream, and “preserves uncorrupted the poetic fantasies of childhood.” This was in the Village Voice, back in 2003. The following year, again in the Voice, I called his Pink Tree, a duet for women, “astutely constructed and beautifully danced” and noted Týnek’s “skill at implying feelings through movement.”

Since then, many a dance writer has noted his gifts: imagination and originality, first of all; then, a seemingly inborn command of structure; an uncanny ability to make movement express emotion and atmosphere; and a dance vocabulary that bonds classical and modern techniques in a way that seems natural, not studied or just plain awkward.

Duŝan Týnek’s Portals

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The cast for Portals was: Alexandra Berger, Ann Chiaverini, John Eirich. Emily Gayeski, Elisa Osborne, Samuel Swanton, Satoshi Takao, and Nicholas Wagner.

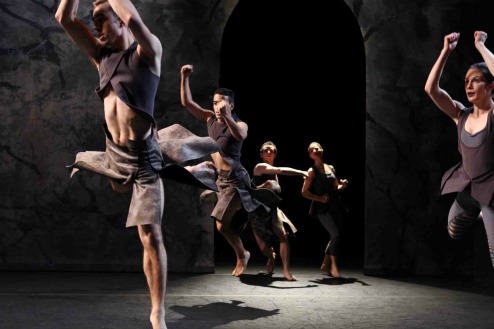

Two dances on the three-work program, Portals and Widow’s Walk, were new this season. Both demonstrate Týnek’s steadily increasing sophistication. Portals, was the most powerful piece I’ve seen from him yet. All eight of the company’s dancers are dressed in Karen Young’s boldly cut leather-look costumes, which bring to mind warriors of ancient Greece or Rome. Both men and women move with gutsy force–and considerable sensuousness–before and behind Mary L. Hamrick’s pale translucent drop cloth. The drop is patterned with jagged gashes indicating cracks (from age or from assault), and punctuated with a huge cutout in the shape of an upside-down U. Hence the portals of the title.

Týnek’s choreography conjures up a tight community (one passage is even influenced by central European folk dancing), with a lust for life, equally feisty in war and mating, actually not separating the two. The full-blooded thrashing action alternates with contemplative moments in which the participants seem to reflect on who they are and, as Yeats put it, what is past, or passing, or to come.

Týnek’s Portals

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

A master of understanding the relationship of dancers to the space in which they move, Týnek makes the most of the different planes of action created by the drop cloth, activating each of them at the same time, but in contrasting ways. For instance, a brief intense duet–a couple making a significant personal connection–occurs in front of this scrim while, behind it, figures in silhouette pace back and forth in a horizontal line, a restless, anonymous parade. Adding yet another vibrant element to the piece, the music, by the post-modern composer Aleksandra Vrebalov, was played live and onstage by the equally daring string quartet ETHEL.

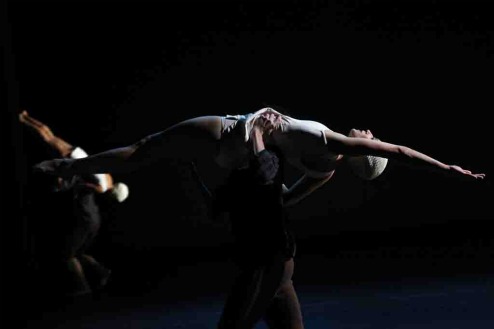

Widow’s Walk refers to the porch-in-the-air that once surrounded many a coastal New England home. Up high, so it provided a view of the waters from which fishermen drew their living, it was cantilevered against the building and reached all around it. The fishermen’s anxious wives paced it, watching for their husbands to return, fearing that, as often happened, they might be seized by the turbulent waves.

Týnek’s Widow’s Walk

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

We meet the wives, then the men. The couples, four of them, rejoice in their mates, but once the men leave, the women revert to their apprehensive stalking. We see the men again, stepping straight towards us, making spasmodic gestures that indicate hard physical labor. Then the women return, now in white tunics and white bathing caps; they have become the sea itself–unpredictable waves with their ironically beautiful lacy edging of foam. Gentle at first, the waves escalate to sheer rapaciousness, as they devour and destroy their prey. The men put up a vigorous fight, but there’s no victory to be had over the mindless forces of nature. The piece ends with the four human couples whipping through the space as if their rage at death will never end. When the men vanish for good they take with them even the comfort that pacing the widow’s walk brought to their wives. What the women feared has come to pass, leaving nothingness.

Widow’s Walk, set to music by Mary Rowell and Phil Kline, was also accompanied, live, by ETHEL.

Týnek’s Transparent Walls

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The evening’s opener, Transparent Walls, set to a score by Vrebalov, a Týnek favorite, presents a dove-like couple who are all in all to each other against a crowd of six who swirl around them, threatening chaos or mayhem. It’s Us vs. Them until the entire environment grows menacing and the lovers, too, are trapped in its lurking perils–perhaps simply in the dire straits of being alive. Although the dancers worked with their typical fervor, this piece didn’t match the complexity and impact of the two works that followed. Nevertheless it made a useful curtain raiser, immediately assuring the audience, through the freshness of the choreography, that it was not going to be mired in the conventional.

Týnek’s flaws? Nothing Bessie Schonberg, the late advisor to the realm of contemporary dance, couldn’t have corrected in a minute: Sameness will dull your audience’s perception, so . . . Don’t use all eight of your dancers for three pieces in a row. Don’t use dusky lighting for three dances in a row. And, while we’re talking about dusk, don’t encourage your costume designers to confine their palettes to muted grays and browns.

Apart from pointing out that many of Týnek’s dances could benefit from further development, I won’t attempt to guess what suggestions Bessie might have made about the choreography. She was a keen-sighted observer and a benign supporter; she could make anything better without undermining its creator.

Duŝan Týnek’s Dance Theatre in rehearsal

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Still, I believe Týnek’s frustratingly slow progress toward wider recognition is not due to artistic shortcoming but, rather, to practical factors. Emerging choreographers of the classical-ballet persuasion seem to have a good many opportunities to make and show their work, especially if they are attached to an important company. Contributing to the repertory of a junior company and creating a dance for a company’s New Choreographers Evening are just two of the options. Contemporary dance troupes don’t have the money to back such programs and many of them (like Paul Taylor’s) are devoted entirely to the work of their founder. At the same time, ironically enough, the big ballet companies are absorbing the work of the best contemporary choreographers (Taylor, Tharp, Cunningham) because today there are few strictly-ballet choreographers as good as these. Now there’s no way Týnek can change the situation on his own (though I devoutly hope he’s doing whatever he can). It’s up to the organizing contingent in the dance world–the folks who brought Fall for Dance into being, for example–to figure out the solution. Preferably soon.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

You make a strong point about emerging choreographers in modern dance not having enough places to show their work. Some possible venues and/or producers that have introduced younger dance makers include: Fall for Dance, the 92nd St. Y Fridays @ noon series, ABT II and Ailey II, Juilliard, Barnard, and Marymount Manhattan. Small, independent companies, such as Miro Magloire’s New Chamber Ballet, also occasionally showcase other choreographers. The problem, of course, is that everything is dependent on contacts and personal trust: The agencies that once tried to level the playing field–The New York State Council on the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts–have been melted down to the point of ineffectiveness. (NYSCA’s treatment of its Dance Panel and of Beverly D’Anne, who headed Dance there so wisely for decades, has been especially disgraceful). But, look, Tobi Tobias has chronicled this choreographer, and perhaps one of her readers will remember him and be in a position to help. It’s aggravatingly slow, no question.

I’m so happy when you see something good.

READERS: PLEASE SEE MINDY ALOFF’S COMMENT, BELOW.

Many thanks to Mindy Aloff for her specific list of places that emerging choreographers might explore to help support their work and enlarge their audience.

It’s wonderful to see Bessie Schonberg’s name mentioned in this

insightful review of Dusan Tynek’s work. If it leaves anyone wondering further about what Bessie might have said, there’s fortunately now a way to hear a bit of her signature wisdom first-hand. Or simply go to FORA.tv and search “Bessie.”

I always read your reviews, enjoy them, and wish I’d been able to say it so well.

I love the imagery you evoke in this piece.