New York City Ballet: The Nutcracker / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / November 25 – December 31, 2010

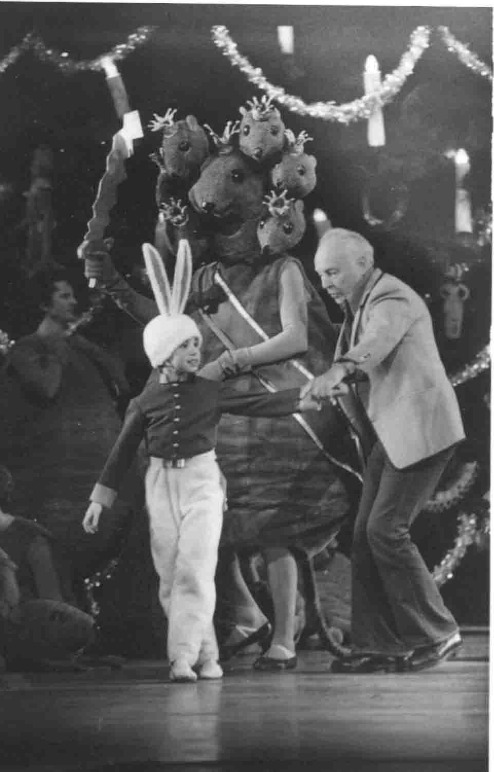

God Is in the Details: George Balanchine, creator of the New York City Ballet’s The Nutcracker, coaching the smallest of the toy soldiers at a dress rehearsal

Courtesy of the New York City Ballet archives

With its premiere in 1954, George Balanchine’s version of The Nutcracker, choreographed for the New York City Ballet and set, of course, to Tchaikovsky’s eloquent score, inaugurated a craze for the Christmastide ballet that promises never to abate. This season City Ballet itself is adding to its annual “Nuts” season (running through December 31) with a live telecast of the ballet on December 13, which will be on view in more than 500 movie theaters cross-country. On December 14, PBS’s Live From Lincoln Center will present the ballet.

All this broadening of the audience for the production is surely admirable. Comparatively few people have easy geographic access to the live version that fills the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center; even fewer have easy financial access to it. Privileged though I am, being a New York-based dance critic, I dare to say that live is best and, moreover, that the Balanchine Nutcracker remains more splendid than all the subsequent renditions I’ve seen.

I attended this year’s opening night performance on November 25. Overall it was lavishly rewarding. Knowing the production so long and so well–and having written about it so often–I gave myself the freedom to report this time simply on the elements that particularly caught my fancy.

Getting to Know You: Fiona Brennan as Marie, clutching her precious nutcracker as she learns how it works

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The Nutcracker boasts a horde of characters, most of them unforgettable. Not all of them are human. The first creature we encounter is a pink-gowned angel with sweeping wings–oversized ones that appeared intermittently in Balanchine’s ballets down the decades, indicating this choreographer’s belief in the power of otherworldly forces. Hovering over the snowy roofs of a modest town and stretching her arms out to a shooting star, the angel dominates the front cloth we gaze at as the orchestra plays the ballet’s overture.

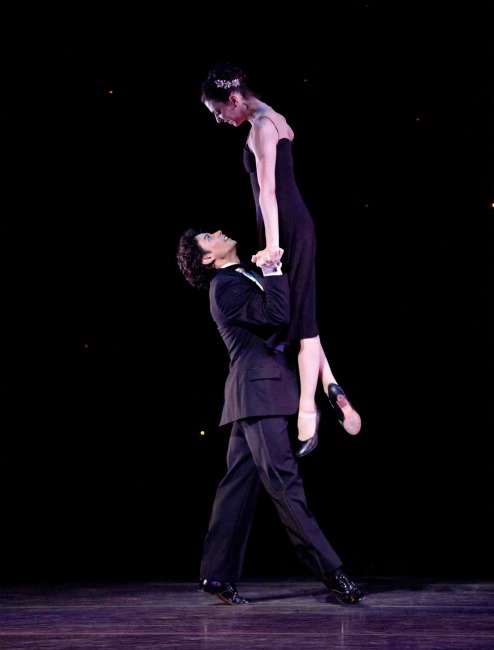

Next we meet a family that lives in the town, the prepubescent Marie, the elder child of Dr. and Frau Stahlbaum, and her irrepressible kid brother, who are celebrating Christmas Eve according to the customs of Germany’s upper middle class in the late 19th century. Given the casting I saw, it was Marie, the child heroine of the tale, who interested me most. Played by Fiona Brennan, Marie is innocent, unselfconscious, and open to what the world has to offer her. So far, it would seem, the world has not let her down.

Brennan is plain-looking (in the way that Mary of The Secret Garden is plain) and miraculously unaffected. As the events of the ballet’s first act spin out, evolving from the domestic to the hallucinatory and the ecstatic, she looks as if she’s participating in real-life happenings, real feelings. Her Marie is a child without guile who experiences everything–even the visionary turns the plot takes–as if it were true.

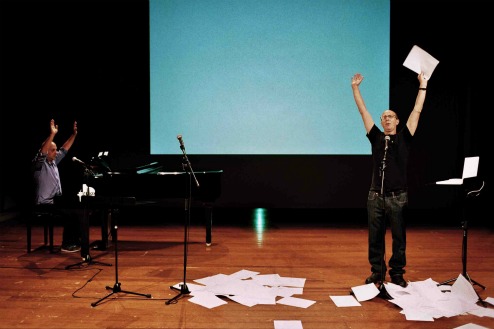

Let Joy Be Unconfined: Sara Mearns as the Sugarplum Fairy

Photo: Paul Kolnik

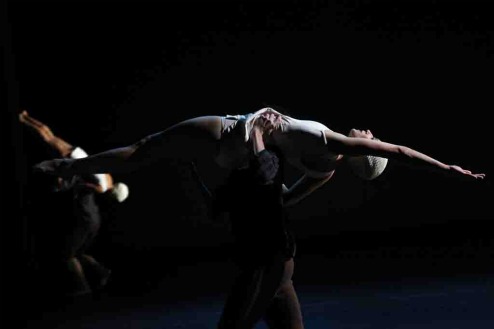

Sara Mearns was the evening’s Sugarplum Fairy, a fact that would make any balletomane or newbie to dancing feel blessed. (Mearns is a dancer whose magnificence is evident at first sight, because of the grace and visceral power of her lush body.) We see her first in Act II, appearing amongst a group of angel-children who’ve been skimming over the stage in geometrical patterns. Once she appears in their midst they make a wide circle around her, like acolytes uniting with their leader. When Marie and the Nutcracker Prince arrive on the scene, she asks them, genuinely wanting to know, “How did you come to be here?” She seems fascinated by the boy’s detailed mime account of the events that drew them to her kingdom–one of the ballet’s tours de force–and deeply grateful for the explanation. In both these passages she behaves like an ideal mother, understanding aunt, or gifted schoolteacher of the young–exuding love and concern for the child or children in her midst.

Towards the end of the ballet, in the grand pas de deux with a cavalier who appears from nowhere–with no narrative identity, but simply to support the ballerina in the duet’s tricky partnering–Mearns continued to defy any impulse a viewer still might have to read her as flat, two dimensional. Alone or with a partner, she invariably works in three dimensions, a moving sculpture with a very human heart.

Admittedly, she didn’t treat Jonathan Stafford–on duty for the occasion–as an emotional foil. How could she? She’d never met him. Suzanne Farrell, another remarkable Sugarplum, handled the problem of the undocumented cavalier just by being grander and more mysterious than her partner, who is needed but not recognized. Mearns, for whom remoteness is not a familiar mood, couldn’t relate to her escort the way she had to the flock of small angels, but was simply magnificent on her own, as if he were invisible (which he was, almost), nailing her every move in the pas de deux, and triumphing in her solos.

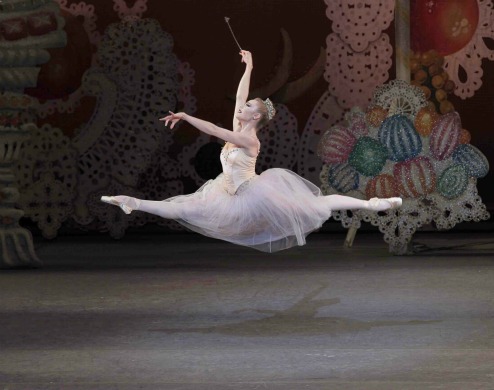

Nature’s Charms: Tiler Peck as Dewdrop in the garden of the waltzing Flowers

Photo: Paul Kolnik

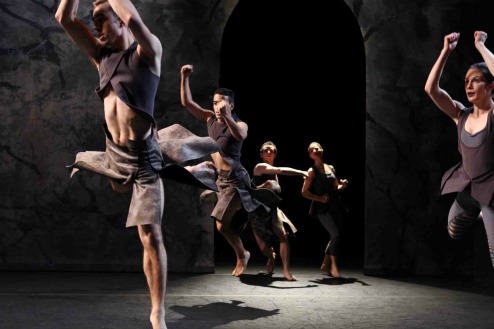

Second only to the Sugarplum Fairy role in The Nutcracker is the brief but dazzling part of Dewdrop, leaping and whirling her way, all clarity and speed, through the mazes formed by a bevy of lyrically waltzing Flowers. I saw Tiler Peck, whose performance was a technical marvel, as it is in any role she tackles. Peck was already an astonishing dancer–and a remarkably beautiful woman–when she joined City Ballet and she matured swiftly on the job, becoming more subtle and sculptural without losing a jot of her panache. I can’t think of any woman now in the company who could equal her as Dewdrop. And yet, much as Peck is almost all you might wish in the part, she still lacks the driving fervor that Heather Watts and Karin von Aroldingen, with much less claim to the title of “ballerina,” projected years back–a kind of ecstatic madness, driven by some sort of life force.

There’s also an invisible being present–a soul that suffuses this production: Balanchine’s, especially Georgi Balanchivadze’s. As a young student in the renowned dance academy of St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Ballet (Pavlova’s school, Nijinsky’s, Nureyev’s, Baryshnikov’s), Balanchine played the Nutcracker Prince. Decades later, creating his own production for the New York City Ballet, he co-opted from the Russian version the mime monologue with which the young Prince explains to the Sugarplum Fairy the dramatic events that led to his arrival with Marie in the Land of Sweets. During his lifetime, as one Prince succeeded another, Balanchine personally coached any boy new to the role. (Two casts alternate in the children’s roles, and the youngsters must abandon parts for which they’ve outgrown the costumes.) Now that Balanchine is gone, the children’s ballet mistress, Garielle Whittle, often tells her charges in rehearsal, “Mr. Balanchine used to say . . .”

Each time you see Balanchine’s Nutcracker, certain passages in it seize your attention, not just for their choreographic deftness–with Balanchine you’ve learned to take this for granted–but for their emotional resonance. Think of the moment in the Party Scene, for instance, when the fathers dance with their little daughters, becoming the girls’ first cavaliers as they’re introduced to the pleasures and strictures of social life. I could name many more, as could all frequent viewers, but will cite just one: Who with any heart could resist the sight of the two children, Marie and her Prince, hand in hand, backs turned towards the audience, walking trustfully toward a faraway star in a darkening snow-covered forest?

When the final curtain fell on these wonders and the audience stumbled out of the theater into reality, I felt–once again, but even more intensely–that The Nutcracker, as conceived by Balanchine, is among the most refreshing and civilized of entertainments.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias