Royal Danish Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / June 14 – 19, 2011

On the final leg of its ambitious coast to coast American tour, the Royal Danish Ballet played New York–the city least likely to let the troupe’s legendary charm dissuade fans from seeing its problems. A central one is repertory. As Nikolaj Hübbe, the company’s artistic director–and an energetic publicity machine–are telling the world at every turn, the RDB hopes to redefine itself by combining cutting-edge contemporary work with its custodianship of August Bournonville’s ballets, performed with regard to the unique style forged by the great 19th-century choreographer. The program offered on the first two nights of the six-performance engagement was not entirely convincing.

Down with Classicism! The Royal Danish Ballet’s Alba Nadal and Tim Matiakis in Jorma Elo’s Lost on Slow

Photo: Per Morten Abrahamsen

If Jorma Elo’s Lost on Slow, made for the Danes in 2008, is any indication of the RDB’s eye for achievement at the cutting-edge, we’re in bad trouble. Elo’s response to the ill-assorted passages of Vivaldi he’s co-opted for accompaniment is simply his familiar spastic perversion of classical dance givens–order, harmony, flow, and, as appropriate, beauty.

Three pairs of dancers, looking too far gone for relationship counseling, delivered this material (including a Munch-like silent scream from a lady being lifted by her cavalier) with determined precision. This made them look so frozen and mechanical that, gargoylish though they appeared, they probably couldn’t pass the entry exam for Scandinavia’s celebrated School for Trolls, which requires some capacity for feeling.

What, I wondered, is the obligatory mid-section pas de deux meant to convey? Crippled emotion? The impossibility of human communication? These are hardly up-to-date themes. Granted, the Vivaldi occasionally lures Elo into crafting a fluent phrase or two, but overall the choreography spurns connections. It’s just one weird gesture after another.

I feel obliged to report that on both evenings that I saw Lost on Slow, the audience applauded the piece with all its might.

Given the agenda Hübbe is proposing for his company, the inclusion of The Lesson, based on a one-act Ionesco play and choreographed by Flemming Flindt in 1963, may have seemed an odd choice, particularly as the curtain-raiser on opening night and the number of performances it was given. The intelligentsia loathes it; the general public finds much to enjoy in the melodramatic horror story of a psychotic middle-aged ballet master giving a macabre private lesson to a dance-entranced nymphet, apparently just one in a long series of victims. To be sure, this ballet is not high art, but it’s a handy vehicle for a company famous for dancers who can act.

Lady Killer: Thomas Lund in Flemming Flindt’s The Lesson

Photo: Martin Mydtskov Rønne

Plot-wise and mood-wise, it outdoes Black Swan at every turn. The setting (wonderfully designed by Bernard Daydé) is a picturesque old ballet studio with a profusion of mirrors, where a rigid female accompanist prepares for the pupil’s arrival. The girl is infatuated with dancing and pretty good too, as it turns out, at incidental bits of sexual provocation. Needless to say, much is made of the gleaming pink pointe shoes that are the symbol of her trade.

From the moment the ballet master enters the room, it’s clear from his twitching, face-averting, obsessive behavior that he’s certifiable. Putting the pupil through her paces, which are increasingly demanding and increasingly bizarre, he couples furtive sexual advances with escalating violence. To make a long story short: Reader, he strangles her. The pianist, his abettor and perhaps an early victim who managed to escape alive, helps him dispose of the body just as the next student is impatiently ringing the studio’s doorbell.

The Lesson fielded no fewer than three men for the role of the ballet master–Johan Kobborg, Mads Blangstrup, and Thomas Lund–and each was remarkable, offering an interpretation that was very much his own. My favorite was Lund, who was the most realistic in his madness and thus the most terrifying. The ballet master’s curdled psyche evident throughout his body, Lund could convince even a veteran viewer of the work that the monstrous events were really happening, to real people, possibly even right now.

As the student, the striking Alexandra Lo Sardo gave a vivid–perhaps too vivid–portrayal of the girl in the traditional vein (of a young woman whose very personality invites trouble). Ida Praetorius, a petite, fair-haired apprentice with the company, still all legs and wide eyes, offered a more innocent, even childlike, take on the character, which I found moving.

Gudrun Bojesun, alternating with Mette Bødtcher, enriched the character of the pianist by adding a surging flow to the robotic moves the choreography assigned her and a dramatic subtext that enhanced the sense of a mysterious and ghastly relationship with the serial killer.

The best thing that can be said about Georges Delerue’s made-to-order score is that it does its job.

When it comes to the Bournonville heritage–the Royal Danes are its custodian, just as the New York City Ballet is of the Balanchine legacy–the company is still unable to find the right way to use it.

The most significant evidence of the Danes’ current attitude to Bournonville was unveiled at the Kennedy Center in DC, prior to the New York City engagement. The performances in the capital were devoted solely to Hübbe’s drastically “new” versions of Napoli and A Folk Tale, two of the three most significant Bournonville ballets extant. Several critics were very tolerant of them; I wasn’t and will explain why, in detail, in a separate piece, to come.

Remembrance of Things Past: Gudrun Bojesen reincarnates Bournonville’s Sylphide

Photo: Martin Mydtskov Rønne

In the Apple, Bournonville was represented by La Sylphide, the ever-mounting dance excitement that concludes Napoli (which never fails to thrill,) and Bournonville Variations. This last is a new concoction–thought up, arranged, and staged by Hübbe and Lund, the company’s Bournonville expert as both dancer and instructor. It’s made up of excerpts, parceled out among nine men, from the so-called Bournonville Classes. These are six set classes–one for each day of the work week–that were put together by Hans Beck, a successor to the great man, mostly from consultations with dancers who had worked under Bournonville. Believe it or not, these classes, in which each exercise was accompanied by a popular tune, were used for decades as the training system for the company and the students being schooled for it.

Originally the classes were transmitted via the monkey-see, monkey- do system from one generation of dancers to the next. In 1979, the classes–and their accompanying music–were scrupulously researched, then published as texts through the efforts of Kirsten Ralov, RDB ballerina, teacher, and stager. A quarter-century later, the classes were recorded as DVDs. Although the videos are duly supported by a pair of books, it’s the availability of the moving images that makes the material, once a kind of professional secret, accessible to just about anyone. Even you, even I, can try out the classes alone at home in our spare time (though I would hardly recommend it).

For the RDB’s dancers and students, the unavoidable boredom of doing, say, Tuesday Class every single Tuesday from as early as the age of six until their retirement in mid-life, was alleviated, at least in the adult echelons, by the men’s creating naughty ditties that they sang sotto voce as they executed the amazingly convoluted chains of steps. “If you can dance Bournonville, you can dance anything,” it is said.

A real Bournonville class performed by professional or pre-professional dancers is, like a Martha Graham class performed by adepts, a thing of beauty and awe for the spectator. For their Bournonville Variations Lund and Hübbe got it all wrong from the moment they thought of theatricalizing the material. What might have worked would have been a demonstration, plain and simple, of a single full class (minus the Bournonville barre, which seems absurd–and even dangerous–to today’s dancers), performed in the starkest of practice clothes, with women admitted to the club. (The set classes offer piquant alternatives according to gender for certain enchaînements.) But no, the perpetrators had to make it macho–something only guys could do, to reinforce the idea that the Danes produce these incredible male dancers (which they do). They also felt they had to make it look like a ballet (which it doesn’t). It has no structure, no narrative or even subtext, no point whatsoever.

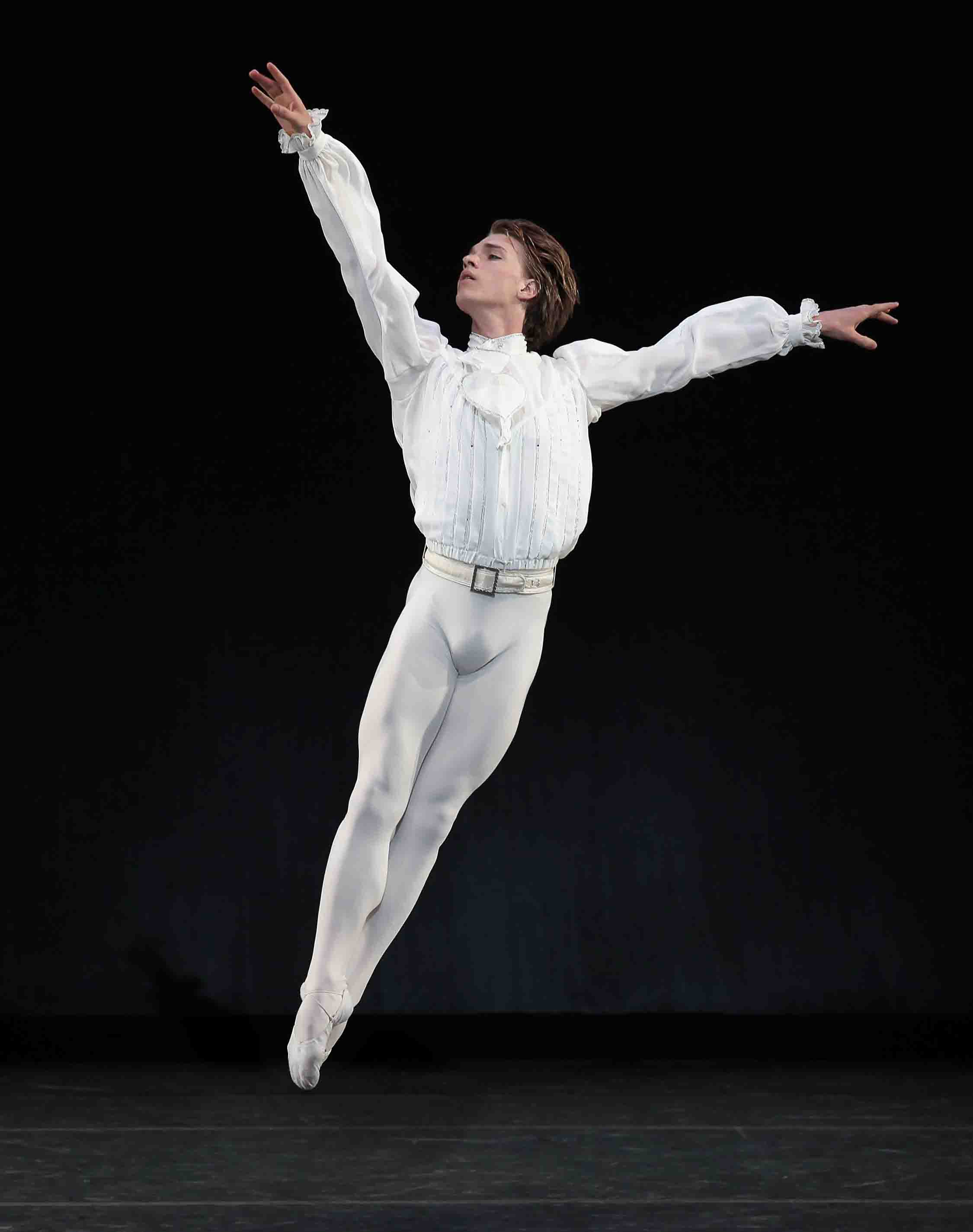

Bournonville Mashup: Alban Lendorf and Alexander Stæger in Bournonville Variations, idea, arrangement and staging by Thomas Lund and Nikolaj Hübbe

Photo: Costin Radu

Perhaps to conceal the fact that their smattering of excerpts doesn’t cohere, Lund and Hübbe gussied it up with glittery black costumes (blame Annette Nørgaard) in the wannabe provocative sex-and-death vein (are the faux-leather pleated skirts that the guys wear at one point a reference to the kilts of La Sylphide?) and raw lighting in garish colors (blame Anders Poll) that Jennifer Tipton would surely condemn as dumb and vulgar past forgiveness. Martin Åkerwall’s music, claimed to be based on the original accompaniment to the exercises, is unrecognizable as such.

Two of the nine dancers stood out: Alban Lendorf, a forceful presence, who stands out in everything he does, and, especially, Lund himself, who has the timing, the ballon, and the calm and tenderness needed for the lyrical phrases in the material as well as the ability to make the more devilish challenges look like an impulsive expression of joy. The others ranged from pretty damn good to not really up to it, the latter revealing the sad fact that Bournonville dancing is no longer the company’s top priority.

The Danes in Italy: Susanne Grinder and Ulrik Birkkjær in the tarantella from Act III of Bournonville’s Napoli

Photo: Costin Radu

More justice was done to Bournonville by an excerpt that concluded the third act of Napoli, which was relatively protected from Hübbe’s changes to the full ballet. (The most flagrant of renovators may turn shy when it comes to meddling with national treasures.) Yes, a bland interpolated solo for the hero and heroine dampened the ever-heightening vivacity for a few minutes. And it was foolhardy to use the newfangled ending in which the lovers ride off after their wedding reception on a glossy white motorcycle instead of the original’s peasant car crammed with bouquets from the pair’s friends, two little boys lustily waving Italian flags on top, and Mama (who said there were no mothers-in-law in ballet?) accompanying them. Nevertheless, what was left was enough to make even the most cynical of spectators admit that life was worth living.

First there’s a pas de six that opens with a lyrical passage for four women and two men. They manage to partner off in a series of patterns that is always logical, never contrived. Meanwhile the mood of their dancing conveys the fondness the participants have for one another and, indeed, for every other dweller in their village, all of whom seem to know each other by name as well as predilections. Then this band encounters a seventh, the man who gets to do the first of seven solos, launching fireworks of an understated prowess that define the Danish dancing spirit.

There are seven solos in all–each as inventive as it is demanding, each spilling forth fascinating and incredibly deft combinations of steps and posture: soaring leaps with one leg curved behind as in the famous statue of Mercury, arms outstretched as if to embrace the onlookers; buoyant jumps in place that are studded with beats, the arms now lowered and quiet; gentle side-to-side shifts suggesting reeds blown by a breeze this way and that; and witty reversals of direction that, no matter how often you see them, always register as a surprise.

It’s Easy When You Know How: Alexander Stæger, members of the Royal Danish Ballet, and students in the company’s school in Act III of Bournonville’s Napoli

Photo: Costin Radu

Everything is executed, of course, as if it were child’s play. The solos are interspersed with the dancing of a linked trio of young women who seem to rank between the soloists and the happy crowd of neighbors cheering them on. (Tambourines play a big role here.) The community is jubilant because the lovers’ story, a fraught one, has miraculously ended in joy, and the audience in the theater finds the mood contagious. The excitement intensifies with an exuberant tarantella and finishes with a communal dance invoking the gods of fertility, as is only appropriate to the occasion.

All the while, on a bridge in the background, there’s a bevy of children clapping in time to the music’s changing meters, gleefully raining confetti down on their elders, and, I’m told, memorizing the solos so that they can perform them when their day comes. Towards the end, some ten of these children–here, the Danish ones, the others being borrowed locals–descend from their perch to skip neatly in pairs through the ranks of their elders. Few onlookers can remain unmoved.

The New York engagement ended with four performances of La Sylphide, the sole Bournonville ballet with a long history in the international repertoire. I went to the last one for sentiment’s sake, because it was the last, and to another that I chose for its casting: Gudrun Bojesen in the title role and Sorella Englund as the witch, Madge, an interpretation that I’ve never seen equaled in the years I’ve been looking at dance.

Bojesen, the RDB’s finest example of classical dancing in the Bournonville style, is, quite simply, the most exquisite Sylphide I’ve ever seen. Enchanting in the contemporary context–as an enticing but impossible vision–she also evokes yesteryear’s Sylphides, whom we know from etchings and photographs dating all the way back to the 1830s, when the choreographer created his version of the ballet, co-opted from the French one and presumably “translated” somewhat to reflect Danish values.

A Danish Ideal: Gudrun Bojesen in the title role of Bournonville’s La Sylphide

Photo: : Martin Mydtskov Rønne

The first thing you notice about Bojesen is her radiance, coupled with the fact that the glow seems to be inextinguishable and to come from within. Yes, such a quality is intangible, but it counts nonetheless; I’d go so far as to argue that no ballerina can be considered significant without it.

Of course technical accomplishment can be discussed more concretely. Take, for example, the extraordinary softness of Bojesen’s footwork. She wears the lightest and most pliant of pointe shoes, which allow her enormous flexibility. And when she moves, even descending from air to earth in a leap or jump, not a single footfall can be heard. This achievement is essentially nonexistent today; in Bojesen’s case, it furthers the illusion that the Sylphide is wrapped in an aura of silence, apart from music.

Bojesen duplicates the virtues of her footwork in the suppleness of her entire body as she moves through space, thistledown style. What’s more, her mimed gestures are woven into her dancing so that the barrier between poetry and prose miraculously dissolves. She plays the Sylphide, rightly, as amoral, a creature of nature, driven by her own desires, and utterly poignant in her death, which results from her loving a mortal man.

Poor James, this creature he’s dreamt of–perhaps created in his imagination–lures him away from a humdrum if safe existence. He’s slated to marry and find contentment with the life laid out for him by family and friends. But how can he resist the Sylphide’s allure? It’s a call to freedom from constraint, to an existence in which nothing is preordained, a call to bliss.

Over the years I’ve seen Englund play Madge several times; on each occasion, she had imagined the character anew. In her single New York appearance in the role she seemed to be a faded beauty with piercing eyes who had fallen on hard times or, like the Sylphide, an otherworldly creature, the sort whose presence we may sense through fleeting glimpses or simply by intuition. Perhaps, Englund may be suggesting, she is a sylphide who has fallen from grace.

Englund makes the witch’s motives complex (as they might be in novels and real life, but rarely are in ballet). Madge craves revenge on James who so feared her presence, warming her frail, chilled body at his fireside, that he threw her out of his house; at the same time she lusts to have him for herself. Once she has duped James into destroying the Sylphide, capturing her with a poisoned scarf, and he lies swooning (perhaps dying) at the her feet, she forces him to look up and see his unseizable beloved being floated into the heavens. But no sooner does Madge gloat over her victory than she’s dismayed by what she’s lost through her jealousy and then, finally–the curtain line is hers–triumphant in her power. Englund conveys all this with an energy and focus remarkable in both their physical and psychological dimensions. Susceptible viewers, and I’m one, are duly shaken.

Ulrik Birkkjær offered a decent James, admirable for the correctness of his dancing, but he was no equal to the two transcendent women in the cast or to my memory of Nikolaj Hübbe’s playing James to Englund’s witch some years ago. That was a blazing encounter of two supremely gifted artists exploring the primal subjects of love, wrath, and power. The possibility of witnessing performances like that, rare though they are, is what keeps me going to the theater.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

and, from the archives:

On the premiere of Nikolaj Hübbe’s production of La Sylphide: The Danes at Home, Seeing Things, September 26, 2003

On the Bournonville Classes: Total Immersion: The Bournonville Festival, No. 8, Seeing Things, June 11, 2005