New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / May 3 – June 12, 2011

The Women in White: Members of the New York City Ballet corps de ballet in George Balanchine’s Symphony in Three Movements

Photo: Paul Kolnik

New York City Ballet opened its spring season with a week and a day of programs devoted solely to the abstract Balanchine ballets that form the core of the master’s repertoire and aesthetic. Balanchine worshippers, often discouraged by the works acquired since the master’s death, flocked to the performances, breathing sighs of gratitude.

The irony of this mini-festival was that Balanchine himself would never have offered such homogeneous programs. An accomplished chef, the choreographer liked to take his metaphors from the culinary art. He’d point out that a satisfying evening of ballets would provide contrasting elements, just as a good dinner furnished varied courses: aperitif, main dish, and dessert.

Even so, I saw all the ballets on offer, some of them twice. I didn’t mind the programming at all. Granted, being a dance critic, I’m in the trade, so to speak. And from the moment I saw Balanchine’s ballets, danced by City Ballet–at my second dance performance ever, early in my teens–I felt that this choreography was my heart’s home.

What made me think that “Balanchine: Black & White,” the May 3-8 mini-festival of the choreographer’s “leotard ballets”–as they’re called because their costuming is only a subtle step away from practice clothes–would bring the productions back to what they once were? Only a viewer’s nostalgia and longing, I assumed–nothing rational.

After all, aficionados have been carping for close to three decades about changes in the original choreography that have crept in–probably from sheer carelessness. The preservation of the ballets as Balanchine left them has often seemed lax, precious rehearsal time being given to one new work after another that’s unworthy of it. As for intentional changes, the general opinion is that Balanchine himself had the right to retool his work and often did (Think of the many versions of Serenade a long-time fan has seen! Think of the ruthless cropping of Apollo!), but that the cut-off for second thoughts should be 1983. I agree almost wholeheartedly.

As for the style in which the Balanchine ballets have been performed for some time, for the most part, they’ve been danced as the rest of the repertoire is now danced: coolly, sleekly, sometimes dazzlingly, but without fervor and without subtext. City Ballet’s dancing is definitely sharper, more physically thrilling than it was in the old days; veteran observers complain that it’s all surface. This, I suspect, is a reflection of today’s culture; if so, there’s nothing much to be done about that. Yes, coaching from dancers who were shaped by Balanchine himself could offer a corrective. I’ve seen Violette Verdy, Suki Schorer, and Merrill Ashley work marvels with their skill. But under Peter Martins’s long reign as Ballet Master in Chief, this practice has not been much encouraged.

Balancing Act: Teresa Reichlen, partnered by Amar Ramasar and Craig Hall in Balanchine’s Agon

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Nevertheless, after a rather lackluster first night–protracted and stormy contract negotiations had been settled only that morning–the “Black & White” project produced a little miracle: Balanchine revivified. The dancers and their ballet masters seemed to have looked closely at the choreography that is their heritage–and their responsibility–and decided it was worth heightened attention and heightened effort. The ballets seem to have been carefully examined and scrupulously rehearsed. Not a single one coasted along on the principle of business as usual. Several of them positively gleamed with the artists’ discovery of the choreography’s richness and wisdom.

The audience noticed. Judging from its fervent applause for choreography of such absolute purity that it is customarily given a polite but tepid response (Monumentum pro Gesualdo, for instance), the public was suddenly charged with enthusiasm. It had discovered that Balanchine’s most subtle, complex, and rigorous ballets were like nothing else on earth. Which is true enough.

The lesson the City Ballet’s administration might do well to take from one of the grandest weeks of dancing that I, for one, have ever witnessed, is that Balanchine’s day isn’t “over” or his work impossible to restore to its original glory. The ballets simply require focused and continuing attention. Providing this is an issue of time and money, which the company needs to budget in proportions somewhat different from the ones that have prevailed for too long. Less, I’d urge, for those gimcrack festivals of new work that yield almost nothing worth keeping; less for choreographers borrowed from Broadway who, after all, fail to entertain; less for choreographers who are “all the rage.” More for Mr. B.

Social Perfection: Maria Kowroski and Charles Askegard, center, in Balanchine’s Monumentum pro Gesualdo

Photo: Paul Kolnik

“Balanchine: Black & White” presented a dozen ballets. They were: Apollo (1928; music: Stravinsky); Concerto Barocco (1941; Bach); The Four Temperaments (1946; Hindemith); Agon (1957; Stravinsky); Square Dance (1957; Corelli and Vivaldi); Episodes (1959; Webern); Monumentum pro Gesualdo (1960; Stravinsky); Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1963: Stravinsky); Duo Concertant (1972; Stravinsky); Stravinsky Violin Concerto (1972); Symphony in Three Movements (1972; Stravinsky); Le Tombeau de Couperin (1975; Ravel).

The works that made the most overwhelming impact on me were Episodes and Symphony in Three Movements. Episodes, whose Webern score fractures the world, coolly and mercilessly anatomizes it, and then, at the very last moment, makes it cohere again, opened the second night of “Balanchine: Black & White” and struck me dumb. I had admired Balanchine’s response to–dare I say extension of?–the music since the ballet’s premiere, for a starkness and strangeness that described the universe as it really was, once you quit resisting the truth.

From the start, it seemed to me one of the most forward-looking ballets I’d ever seen (or would be likely to see). I was fascinated by its spare and seemingly arbitrary movement, by the fact that stillness (in the music and in the motion) was a major player in the proceedings, and by Balanchine’s fearless answer to the question What if you removed all the rules, or, if you will, the conventions of choreography? I was even delighted by the fact that, at the end of a musical segment, the dancers simply stopped, then walked–almost like pedestrians–to the spot where they would take up again when the music resumed.

Last week, still remembering the pleasures provided by the original cast–the pioneers of Episodes, as I think of those dancers–I saw the perfect polished version of the ballet, meticulous in every respect. The time in which it is set still seems to be the future, while the principles guiding the choreography are in no way estranged from classicism.

For almost four decades, Symphony in Three Movements has represented the thrill and terror of exorbitant energy as well as the strangely inverted results that occur when that force is played out. Just now, it could serve as a parable of our time, in which individuals, communities, and whole societies disintegrate, besieged by an overload of information and the simultaneous failure of authentic communication–or, simply, succumbing to the all too human impulse toward conflict and violence.

The ballet’s tribe of formidably svelte, long-legged women in skin-tight white leotards, posed in a diagonal line from one corner of the stage to another is one of the most compelling opening images ballet has to offer. Balanchine gives you just a few seconds to take it in, and then has these women, whose type he has essentially invented, prance into motion with irrepressible energy, ponytails flying and whipping. When that line reforms at the close of the first movement and creates the optical illusion of a current (of a surging river? of electricity?) swirling along its path as, fluidly, one after one, the women turn to shift the direction in which they’re facing-well, you know you’re not in Kansas anymore.

In between those two moments Balanchine shows us the rest of the world: five women in black, perturbers of calm, often in a coiled-to-spring position, abetted by male partners, and three leading women whose leotards (and hair ornaments!) are in three just slightly, and deliberately disconcerting, incompatible shades of red. They are also accompanied by partners and may represent humanity.

In the third movement the full cast is deployed on an invisible grid, sometimes becoming the grid itself, by means of line-ups and arms stiffly outstretched to the side. The dancers might be soldiers or prisoners; either or both, it’s up to you and your own fancy (as is, needless to say, everything in my own “interpretation” of this ballet). The women in white, stationed on the border line between the stage and the wings, move into and out of concealment gesturing with their arms in a code no one can crack. (Whom you can see and when you can see her depends on where you sit. This is not simply a given observation of art you look at, but a useful lesson in life.)

Finally the male contingent moves forward and, laid out as if on graph paper, stretches full length on the floor in push-up position, heads toward the audience, poised for action, like patriots futilely declaring, like so many that went before them, “We’re ready.” Ready for what? Annihilation?

The middle section of the ballet is an eerie duet for one of the three leading ladies and her partner (I saw Janie Taylor and Jared Angle) in the roles originated by Sara Leland and Bart Cook.) You might think that, as is customary in classical-ballet duets, they’ve come together in privacy to explore–or make–love. In the world Balanchine has envisioned with this piece, there’s no such thing as love; it’s been blotted out by circumstances. Their exchange is one of bodies reduced to stylized movement colored by, perhaps, Balinese (that is, “foreign”) dancing, and it ends with the partners significantly leaving the stage in opposite directions, rather than any hint of bonding.

One of the best things about Symphony in Three Movements, I hasten to add, is the tremendous impression it makes even on those who join with Balanchine’s own (at least public) stance against interpretation.

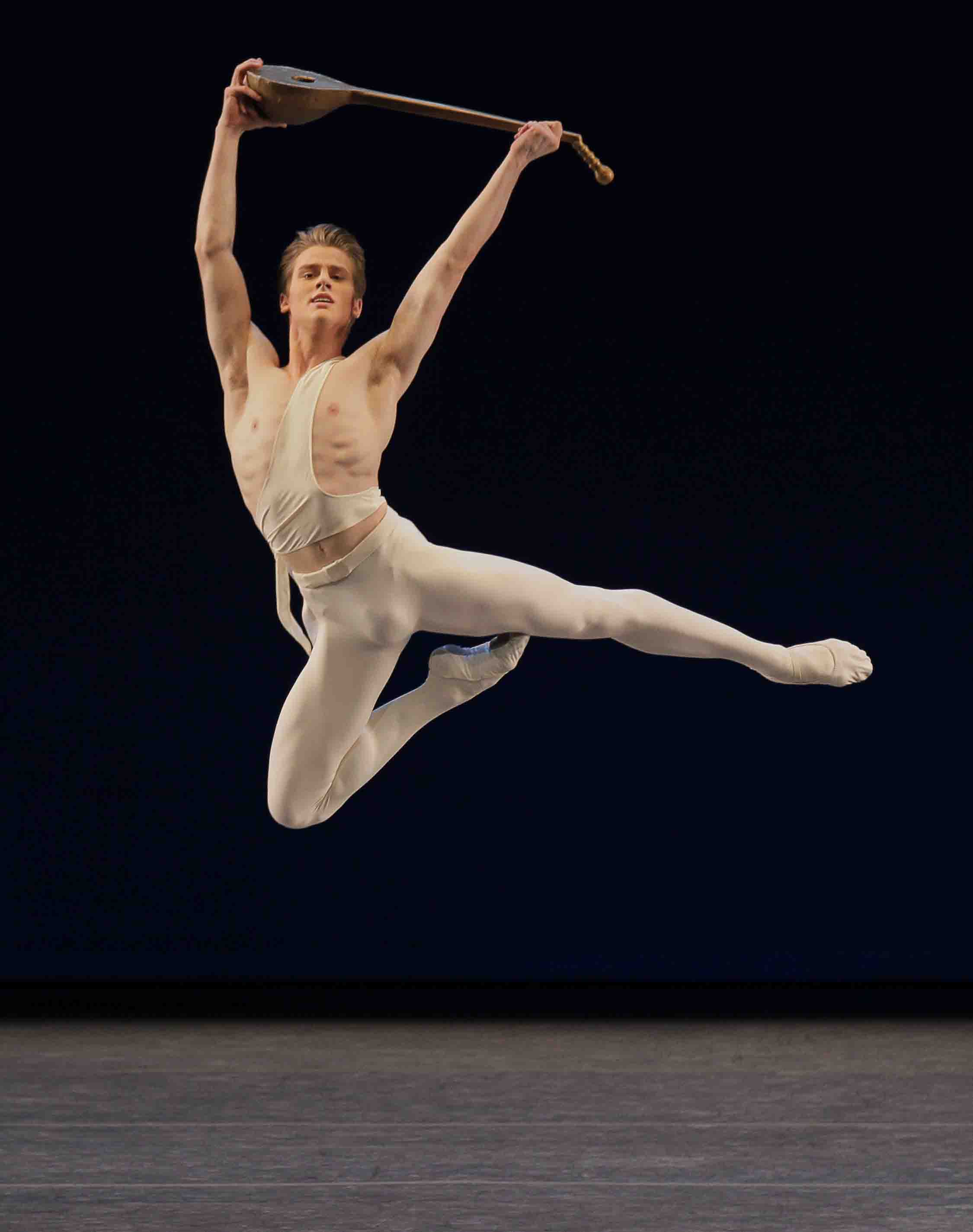

Young God: Chase Finlay in Balanchine’s Apollo

Photo: Paul Kolnik

As for the dancers seen in principal roles in the course of the “Black & White” project, two men in the rising generation stood out particularly. First among them was Chase Finlay, who joined the corps de ballet in 2009. With his thick blond hair and expressive mouth, he can look like a pouting Cupid and is surely a candidate ripe to rival Justin Bieber as a darling of the screaming tweens. Fortunately he has better things to do, given his prodigious technique and his ability to possess the stage with the aplomb of a seasoned star.

Entrusted with the lead in Apollo, Finlay renewed the vitality of this pivotal ballet, Balanchine’s first masterwork. Clearly he was using everything he had been told or read about the role, and his boss, Peter Martins, had been one of its most memorable interpreters. Still, Finlay made it spontaneous and his own. Perhaps he identified with his character: a very young man learning the job of being a Greek god.

At moments in Apollo, Finlay recalled the young Baryshnikov, not merely in looks, but so on top of the challenges in the choreography, he could lend an impish touch to the playful passages with his troika of muses. In Duo Concertant, he was remarkable again, impersonating an ordinary fellow, one your daughter might be dating (assuming they were both into classical music). Here he partnered Megan Fairchild, who, though technically adept, falls all too easily into the trap of cloying sweetness. Finlay’s presence brought fresh air to the ballet (which has an admittedly hokey premise) and to his ballerina.

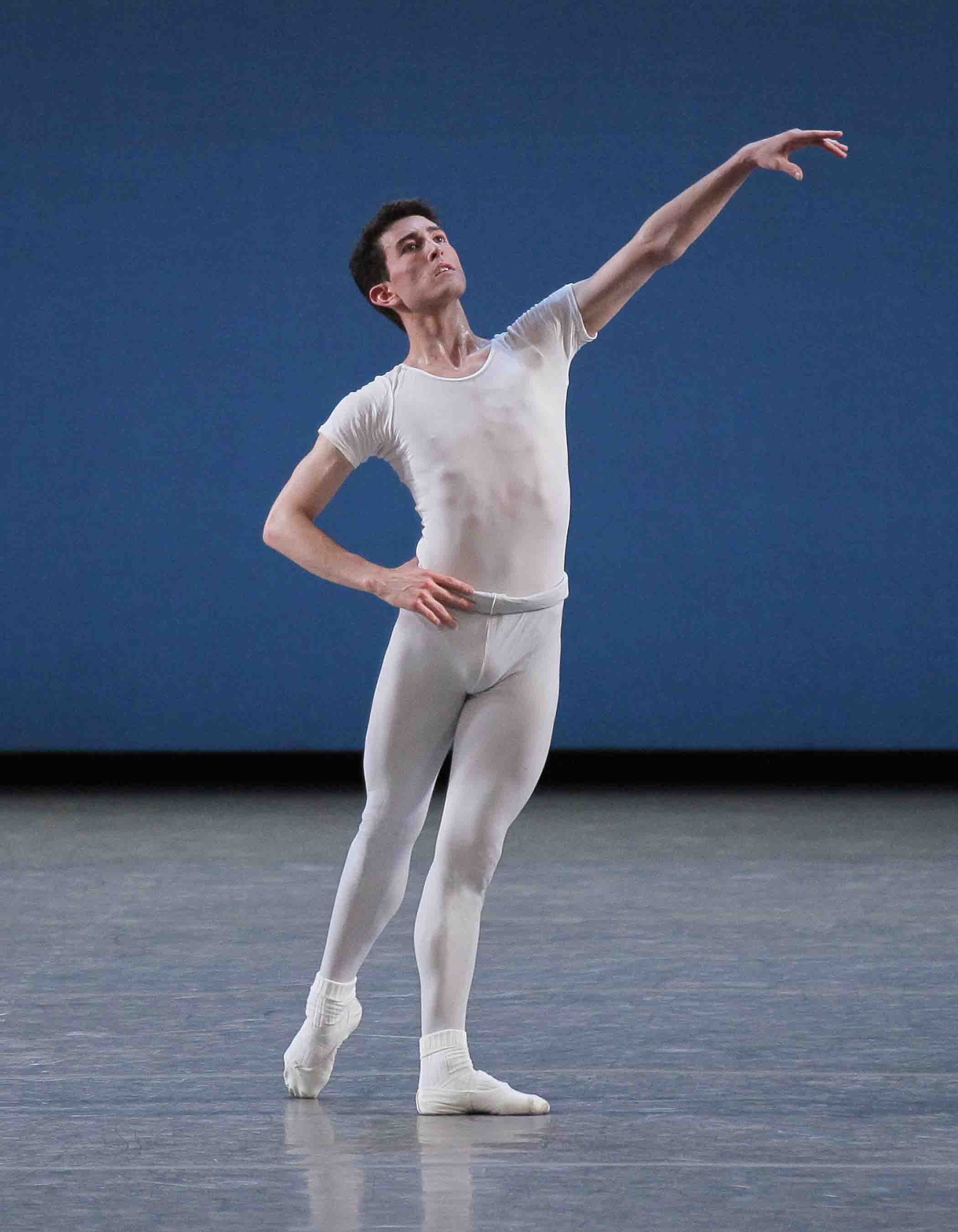

A Princely Meditation: Anthony Huxley in Balanchine’s Square Dance

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Nowhere near as sophisticated in stage presence as Finlay, Anthony Huxley, a corps member since 2007, is nearly his equal in promise for the future. Dancing the male lead in Square Dance, the opening ballet in the “Black & White” series, he was a wonder–from his compact, beautifully proportioned body to his flawless coordination. He seems to be airborne by nature, not through effort or training. He’s not so much a high-flyer, though, as forever buoyant.

He has dark, close-cropped hair and a somber, innocent face, like that of a thoughtful child. There’s nothing in the least pushy about him, no Mr. Bravura here, just dancing that’s at once a plain, quiet statement and irrefutable proof that classicism still counts. He makes every one of the old steps look newly minted.

In the celebrated male solo that Balanchine made belatedly–to fill the plea of the cast’s women for a breather after the extra-frisky section they called “Chase the Rabbit,” Huxley already vies with the finest of his predecessors, Bart Cook and Peter Boal. From the moment he appears on the otherwise empty stage, he’s surrounded by an air of mystery, aloneness, and singularity. He might be the prince of a lost kingdom. As he proceeds through a chain of small phrases, made more of posture and gesture than the heat and flow of ordinary dancing, he evokes a mood of remembering and longing for a state he once inhabited, but which has disappeared, leaving him only dignity and resignation.

Caught: Maria Kowroski (airborne) in Balanchine’s Monumentum pro Gesualdo (alternating in the role with Teresa Reichlen)

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Among the women, the most evocative performances were given by principals whom I’ve admired for some time now. Teresa Reichlen, the long-legged epitome of poise, was exquisite in Monumentum, her pale face grave, her movement sublimely calm and clear, her hands making filigreed gestures. She made me think of a medieval princess–perhaps the one in the breathtaking, enigmatic Dame à la Licorne tapestries at the Cluny museum in Paris–performing a rite she had embraced as her duty. Even when she was thrown from the arms of one pair of men, left for a nanosecond to float unsupported in space, then caught by a second pair, she maintained an unperturbed arabesque.

She was equally amazing in the Choleric section of The Four Temperaments, a fiery figure who looked dangerous to touch but one that kept the world steady on its axis. Even a small mishap revealed her phenomenal equanimity. In the introduction to the second pas de trois of Agon, she balanced on pointe on one foot, looking directly out at the audience–and somehow failed to connect with her supporting partners’ hands. Slowly and serenely, she tilted sideways, like Pisa’s tower, without a tremor, until she was rescued. A few minutes later she was performing the intricately timed solo to castanets as of she’d never been anything but safe.

Reichlen has so perfected the qualities that constitute her profile, it might be time for City Ballet to try casting her against type–say, in roles that require warmth and voluptuousness. There may be more to her than meets the eye.

Sara Mearns has been whipping through the City Ballet’s repertory at a pace her admirers can barely keep up with. I’d never imagined the company would think of her for Concerto Barocco, but there she was, lending her luscious fluency to just the right degree as a foil for Maria Kowroski, the queen of adagio dancing, who naturally got to do the central duet with the sole man in the ballet.

Mearns’s role in the final section of Episodes was a triumph. After all the ingenious, unsettling dislocations Balanchine created to the stark atonal Webern music used for the bulk of the ballet, here he matched the composer’s tribute to Bach–an arrangement of the Ricercata in Six Voices from A Musical Offering–with choreography that, still spare, restores the idea of harmony. Mearns was a natural for the part.

Two other key women on the roster, Maria Kowroski and Wendy Whelan, were to be praised more for the intelligence with which they conceived their roles than for sheer theatrical impact. Kowroski, luminous early in her career, now fails to engage fully with what she’s doing; many of her effects are beautiful–in Monumentum she was crystal clear and at the same time tender as a rose petal–but still remote. Her performance in Stravinsky Violin Concerto, partnered by Amar Ramasar, earned a second curtain call, I felt, because she had understood the nature of the choreography and how she could dance it most effectively, not because she appeared to be experiencing the moods and events it implied.

Though Whelan still looks as if she’s made of spun steel, her technique has, unavoidably, been ebbing in recent years; her projection of acute sensitivity, increasing. While she’s been unequalled among her peers for her interpretation of roles conceived in the land of regret and pain, her natural range has always been limited. She has worked admirably to extend it, and frequently succeeded to a point, but she still lacks the confident joy and the claim to conventional beauty that are hallmarks of the traditional classical ballerina. But then the New York City Ballet is hardly a traditional classical ballet company.

Thanks to George Balanchine, the company is the chief custodian of a huge percentage of the most remarkable ballets created in the 20th century. As the “Black & White” festival proved by giving such pure and energized productions of the abstract works, Balanchine’s ballets cannot be condescendingly dismissed as monuments of the past, relegated to the history books, thought of as relics for a museum. They remain signposts pointing to the future of the art.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

I knew I should have cut class and just gone. The problem is, of course, I am the professor. It’s an excuse I now regret.

Timely of you to say that “it might be time for City Ballet to try casting [Teresa Reichlen] against type”–she débuted in the “Tales of the Vienna Woods” section of “Vienna Waltzes” the other day, and was absolutely heart-stopping.

Nice piece, especially the cadence.

What a great piece! A précis, an analysis, and a love letter all rolled into one.

Thank you for a review as luminous as the dancing it evokes in memory and imagination.

These days I hardly bother going to NYCB, with its awful premieres and gimmicky PR. But I hate to have missed that “Black & White” week. (I had commitments out of town.) Despite the propaganda hailing Forsythe and his ilk as “progressive, innovative” and all that nonsense, the Eurotrash idiom represents tremendous regression from Mr B’s apex. You are so right: Balanchine still looks like the future—but only when it is performed as if it is the present, as if the ballets are new minted, with the ink still wet, so to speak.

Stunning critique. I agree with everything, and would only add Jerry Robbins to the classical mix. (I can take only so much Stravinsky, alas, before I “tune” out.)

Thanks for your insights. I believe that we have the New York City Opera to “thank” for the Black & White week. The Opera gave its unused time over to City Ballet, and Peter Martins obviously used it well and to good effect. As in Shakespeare’s day, Time and Space and Circumstance were essential to great theater, and Balanchine in these pieces is nothing if not theatrical.

Brava!

Three cheers!

Thank you for this perceptive and informative review. I feel that, overall, Maria Kowroski is more suited for the Black & Whites than Sara Mearns. I am just a layman, but I saw all the performances.

Note: Charlotte Christensen, who sent this Comment, writes about dance and the visual arts from her base in Copenhagen.

What a fantastic review! Just for a change I wanted to be at the New York City Ballet together with you; before, I always thought we would not be very pleased.

Yes! Great review for great events. Thank you.

Kudos…

Thanks for this piece. Where else do you write?