American Ballet Theatre: Ratmansky, Wheeldon, Millepied, and Tudor / Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / May 24-26, 2011

The lone mixed-repertory program in American Ballet Theatre’s eight-week spring season at the Metropolitan Opera House attempted to lure today’s audience, addicted to multi-act story ballets, to a more varied–and riskier–scenario. It offered new pieces by the two most gratifying classical choreographers in our midst (Alexei Ratmansky and Christopher Wheeldon), another by the fellow most avid to join their ranks (Benjamin Millepied), and the revival of a work by a past master (Antony Tudor), though not of one of his masterworks.

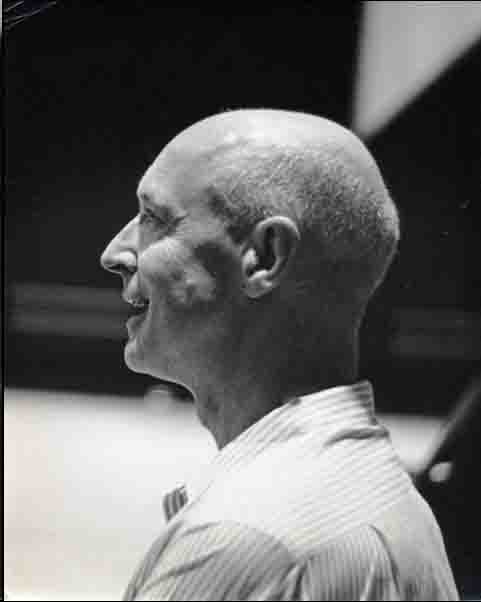

Antony Tudor (1908 – 1987)

Photo: Elizabeth Sawyer

In Dumbarton, set to Stravinsky’s neo-classical Concerto in E-flat (Dumbarton Oaks), Ratmansky devotes himself to one of his specialties–making an ensemble fascinating in itself. The choreography offers a perpetuum mobile opportunity to ten dancers, who are also seen, at intervals, as separate couples. (Imagine a video camera zooming in on a particular pair in a community to reveal more and more about them.) The full-group patterns look like quick-shifting kaleidoscope images that have been released from their customary geometric boundaries. Ratmansky’s flair guarantees that the unleashed, unexpected patterns never once lose their coherence.

Nearly four decades before Ratmansky created his piece, Jerome Robbins used the music for his Dumbarton Oaks, choreographed for the New York City Ballet’s 1972 Stravinsky Festival. Seasoned viewers remember that ballet, if at all, as a feeble effort, having something to do with recreational tennis, with the costumes vaguely reflecting the dapper Twenties. Now the score–like so many things in life–has been given another chance. This dance-historical footnote would be irrelevant if there weren’t hints of Robbins’s predilections in Ratmansky’s ballet–not in the steps and style, but rather in its evocation of an appealing past time and place. In the Ratmansky the idyll is simpler and sweeter than contemporary urban life. Richard Hudson’s costumes–with their all-cotton look–suggest ordinary folk living good lives far from big cities. Without the least bit of sentimentality or fakery, everyone in this imagined realm looks young and beautiful.

And Then Suddenly, Without Warning: The full cast of Dumbarton, choreographed by American Ballet Theatre’s Artist in Residence, Alexei Ratmansky

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

The tone of the choreography is largely playful, though when the music slows and grows quiet, Ratmansky lets the atmosphere of the dance become more meditative. Then, with almost no warning, one woman collapses in her partner’s arms, falls to the floor, and is borne off, body supine and rigid, as if in a funeral procession. It made me remember being a fourth-grader returning to class from spring vacation and having the teacher announce to the room of 28 children and one empty seat fused to a cleared desk, that Charlie–stickball champ, ramshackle scholar, the kid with the irresistible grin–had died. Charlie? Die? How could this happen? He was only ten years old! Life’s natural order had been hideously disturbed.

The music returns to an upbeat mode and Ratmansky, always prone to let joy have the victory over gloom, has the stricken woman return unharmed, unaffected by what has occurred a few moments earlier. It’s the spectator who remembers.

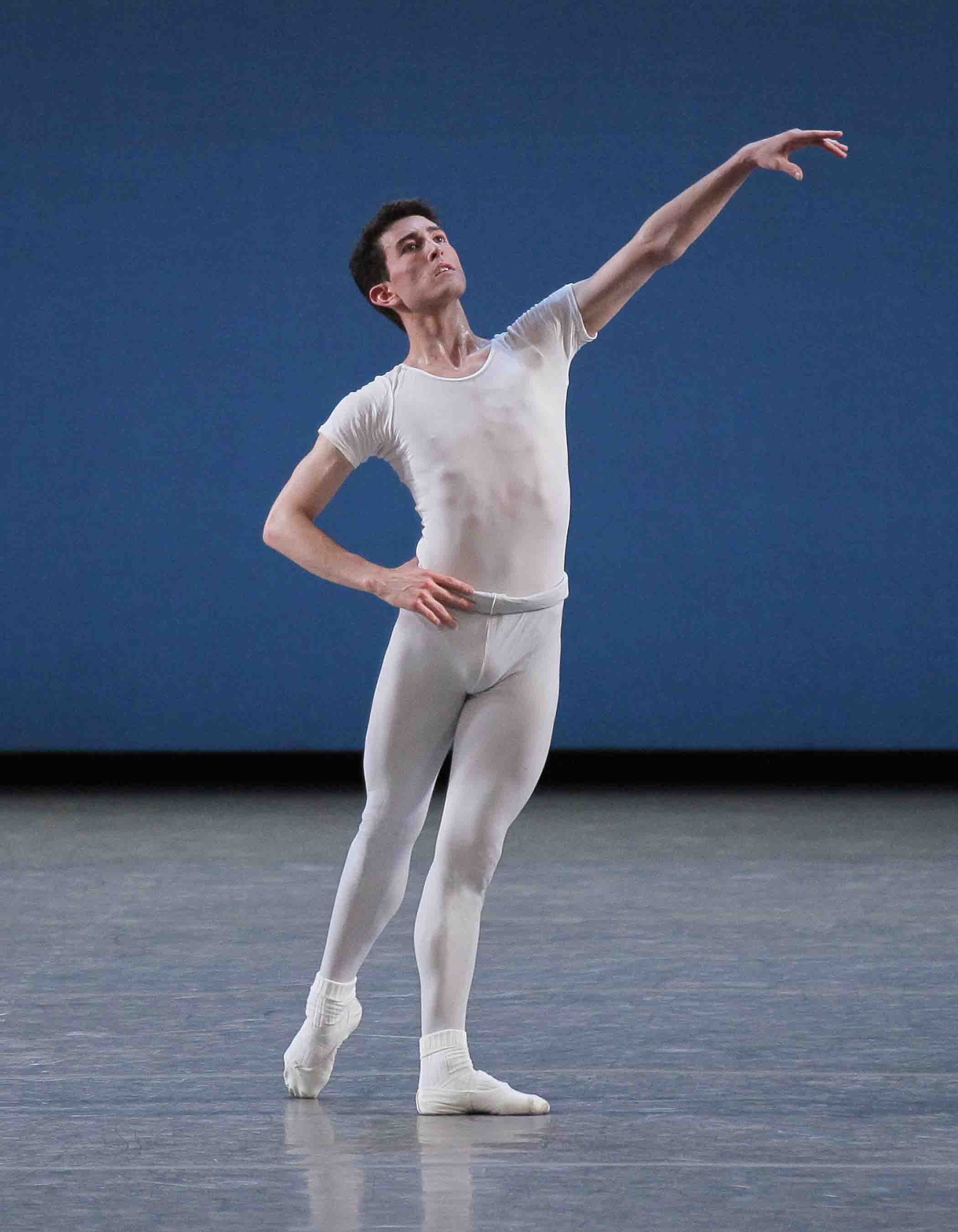

Set to Benjamin Britten’s Diversions for Piano and Orchestra, Wheeldon’s sleek, handsome Thirteen Diversions shows the choreographer taking a step his audience has been hoping to see for quite a while. Like most of his work, the piece is exquisitely organized and inventive when it comes to steps, all the while adhering to classical principles and, for the most part, the classical vocabulary. But now, at long last, in a ballet that ambitiously has four principal couples sharing time and space with an ensemble of 16 (in itself no mean feat), Wheeldon has been able to access some emotion that actually looks genuine. It makes all the difference.

Typically, he reaches for design that is over-impressive. Brad Fields, credited with the lighting, has also created the décor: projections on the backcloth of huge fields of saturated color sliced by streaks of white light. The hues change with each of the thirteen passages. The eye is bombarded. I imagine that Jennifer Tipton, who has proved incontrovertibly that subtle lighting is the most persuasive, would be appalled.

Bob Crowley’s costumes, too, are over the top. The principals wear white; the ensemble black. The theme is dinner-jacket tops for both genders (the men’s have a 19th-century look, while the women’s are feminized). Below, the men wear danseur noble white tights; the ladies sport knee-length fluffy skirts. The predominant fabric appears to be a lush, infinitely pliable satin, easily the most sensuous of materials. And have I mentioned the ballerinas’ hair-dos? Very chi-chi. Must have cost a fortune.

Deep Song: Marcelo Gomes and Isabella Boylston in Christopher Wheeldon’s Thirteen Diversions

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Given the high style of all this eye candy, the dancers’ demeanor is formal–until, in duets for two of the couples, myriad and mysterious forms of love surge to the surface. The emotions are not acted, though; they reside in the choreography. And the dancers, blessedly, make them happen, without distorting them with personal comment. Gillian Murphy and David Hallberg seem to enjoy an early-summer romance, the sort of thing where to abandon oneself to love is no big deal, but only natural, given the circumstances. Late in the ballet Wheeldon explores the other end of the amorous spectrum, giving the wonderful Isabella Boylston and Marcelo Gomes a gorgeous duet that is fraught with passion. It describes a bonding so deep and complicated that it hurts as often as it succors. In this pair of duets Wheeldon accesses a humanity he previously chose to ignore or needed to grow into. No artist is complete without it.

Troika, the Russian word for a carriage drawn by three horses, is used informally to refer to the passage in Balanchine’s Apollo in which the exuberant young god gathers his three muses and drives them along at a brisk pace. It is also the name of Millepied’s latest ballet, which is, in my opinion, the best work he has produced so far. Granted, this is not much of an endorsement, but it’s a sign that, having spent a number of years learning his trade with uninspiring results, Millepied is now capable of constructing a ballet that is workmanlike instead of awkward, hollow, and/or baffling.

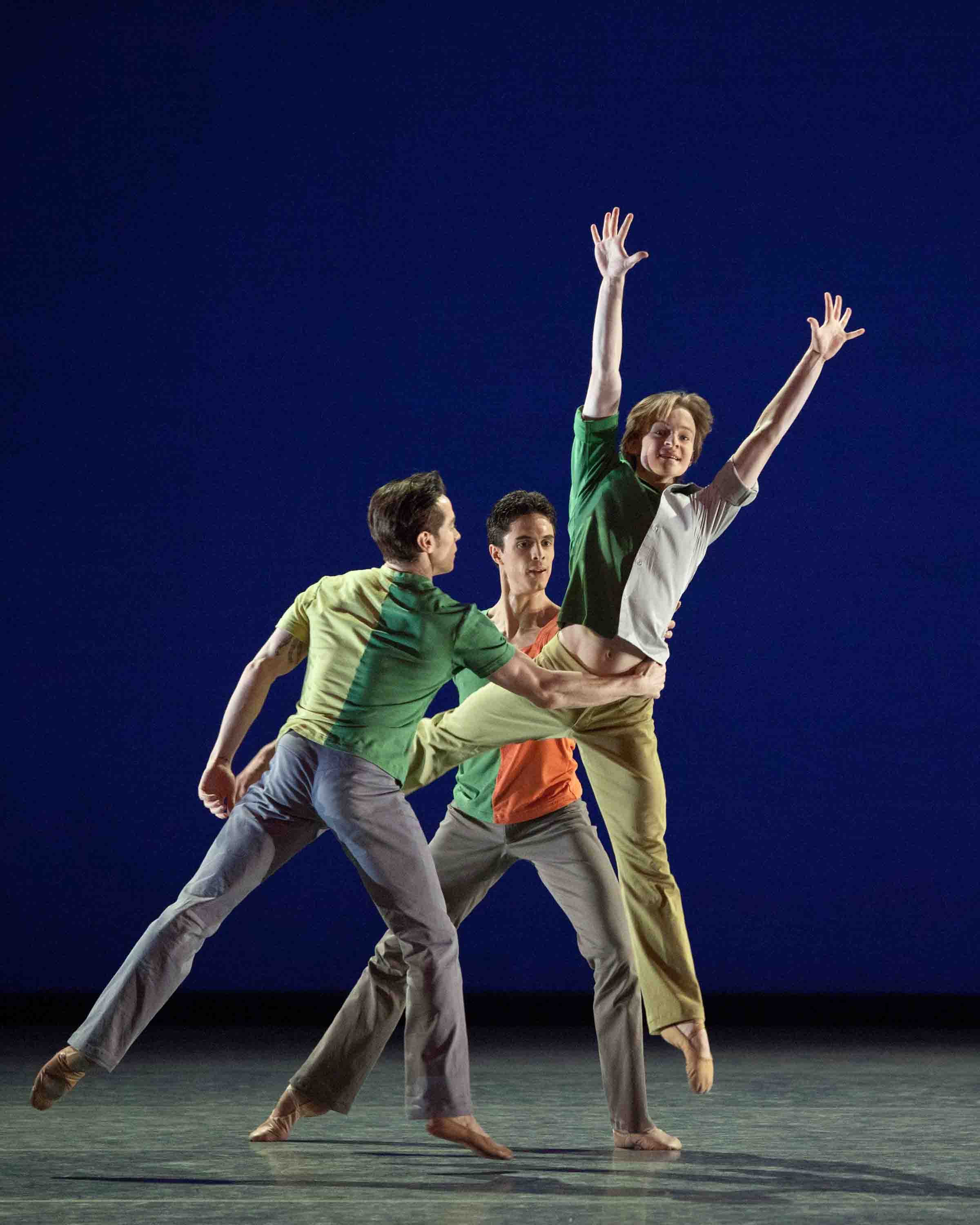

Troika, set to Bach cello music, gives us three guys of different heights–small, medium, and large, so to speak–although, strangely, nothing much is made of this in the choreography. Channeling Jerome Robbins in his Interplay mode, Millepied makes them best buddies, regular guys who are, you know, just hanging out, fooling around. Since the performers are not street kids but talents subjected to the long, arduous years of classical-dance training, it’s hard to suspend your disbelief in the premise.

Boys Will Be Boys: Sascha Radetsky, Alexandre Hammoudi, and Daniil Simkin in Benjamin Millepied’s Troika

Photo: Mikhail Logvinov

The fooling around is, inevitably, full of feats. They’re acrobatic, jokey, show-offy, competitive without rancor–in other words, boyish–and no doubt intended to impress and charm the audience at the same time. Toward the end of the ballet, when even disarmed spectators may well have had enough and the “boys” are drenched in sweat, the tallest fellow leads a slow meditative section (a typical Robbins tactic for offsetting hijinks) in which we can assume the three are brooding over their inner feelings and perhaps their friendship too.

The dancers were swell. I preferred the first cast–Daniil Simkin (short), Sascha Radetsky (average), Alexandre Hammoudi (tall)–yet couldn’t help feeling that these men were wasting their talents with a project short on authenticity. The cellist, Jonathan Spitz, who played onstage, was swell too.

What can I say about ABT’s revival of Tudor’s 1967 Shadowplay? The choreographer’s small but utterly unique oeuvre, by turns tragic, tender, and acerbic, saw deep into the human soul, fusing gesture with feeling. When Mikhail Baryshnikov headed ABT, he called Tudor the company’s “conscience.” Tudor’s ballets–among them Jardin aux Lilas (Lilac Garden), Dark Elegies, Pillar of Fire, and The Leaves Are Fading–have long been considered the company’s legacy. But time has indeed gone by. Nowadays even the masterworks I’ve named fail to attract the general public, whose taste has been blunted by the large, the gaudy, and the next new thing.

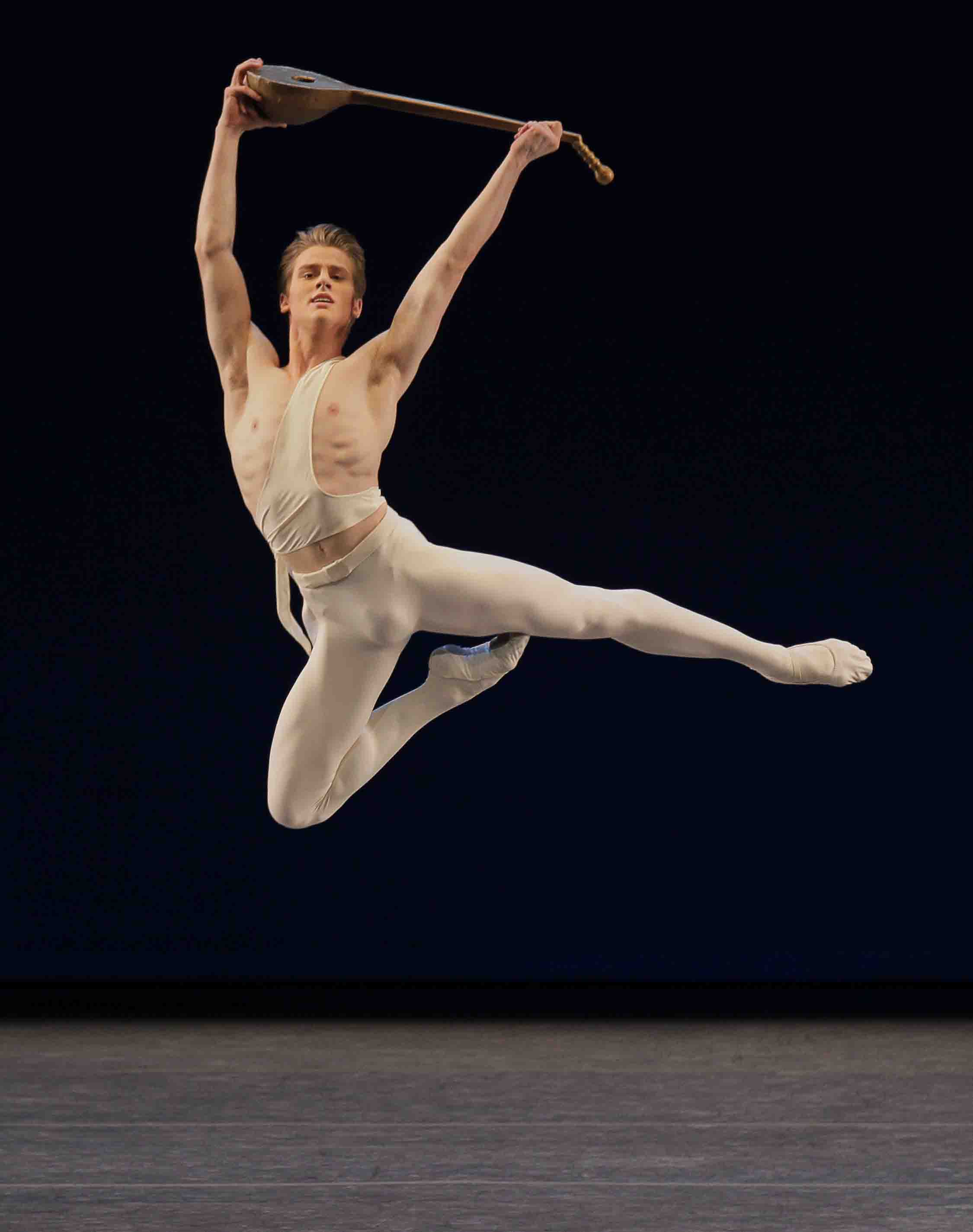

It’s possible that Shadowplay doesn’t stand a chance. It has been considered a “difficult” piece from the moment of its creation–hard to understand and as much posture and gesture as full-fledged dancing. It’s a mythical affair, reflecting Tudor’s growing commitment to Buddhist thought and practice. It describes, all too vaguely, a young man’s journey toward enlightenment as he encounters the denizens haunting his jungle home. The eerie music is Charles Koechlin’s and relates to Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book, which also informed Tudor’s choreography.

The hero, called Boy with Matted Hair, is a human stripling, innocent and vulnerable, curious, too, but firm of purpose. He stays close to his meditation spot at the foot of an immensely gnarled tree with spidery branches as various forces arrive to tempt and torment him. There’s a tribe of Arboreals, monkeys low on the spiritual totem pole; then the Aerials, six women in balletic versions of Cambodian dress; the Terrestrial, a gorgeous hunk of a man costumed like a Hindu god, who dominates the Boy sexually and belatedly receives his comeuppance; and the Celestials, two male bearers carrying a seductive woman high above the earth. She turns out to be a real harpy, hardly a desirable erotic companion. Presumably by force of will, the Boy overcomes these distractions to achieve Nirvana.

In the intermission a woman seated behind me, who had evidently seen me scribbling notes in the dark, asked me if I could explain the ballet we’d just watched. Before I could think, I blurted out, “No.” For the sake of civility I quickly made amends, but I suspect my initial response was closer to the truth.

You can tell the ballet is considered “important” by the artists who’ve danced the leading role. Anthony Dowell, perhaps the most pure and touching male dancer in history, originated it. Baryshnikov took it on in ABT’s 1975 revival. Herman Cornejo, who has an uncanny ability to grasp and then produce the style of any role he covers, was slated to portray the Boy in the current production but was waylaid by injury; Craig Salstein turned in a sensitive performance in his place–all tender-footed gait and unsullied soul–while Daniil Simkin appeared in the alternate cast.

Below, a glimpse of Anthony Dowell and Derek Rencher in the original production of Shadowplay by the Royal Ballet:

I hope the ballet remains in ABT’s repertory long enough to give Cornejo his chance in it and to give me another chance to see what the music critic Andrew Porter saw in it: “If the ‘content’ of Shadowplay could be . . . verbalized,” he wrote, “there would be no need for the ballet. Words can be only a crude pointer to the kind of work it is, a work in which Tudor, as ever, communicates in a clear, eloquent imagery, with great delicacy of nuance, what can be really experienced but hardly translated into any other medium.”

© 2011 Tobi Tobias