American Ballet Theatre: The Nutcracker / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC / December 22, 2010 – January 2, 2011

A tree grows in Brooklyn–with a vengeance. At BAM’s Howard Gilman Opera House, American Ballet Theatre’s brand-new Nutcracker, by Alexei Ratmansky, followed on the heels of the Mark Morris Dance Group in The Hard Nut. Same evolution-of-the-girlchild theme (more or less), same glorious Tchaikovsky score. Musically, you can’t fault the nation-wide and ever-expanding Nuts endeavor. Choreographically and theatrically, it’s another story. (Despite the popularity of his own version, and with due respect to Balanchine, Morris claims that Walt Disney did the best job–in the evergreen movie Fantasia.)

Gotcha: Justin Souriau-Levine as Little Mouse in Alexei Ratmansky’s The Nutcracker for American Ballet Theatre

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Ratmansky’s version of The Nutcracker for ABT comes after two earlier tries, first with the Kirov Ballet and then with the Royal Danish Ballet. On both occasions the stakes were against him, primarily through having his creative freedom thwarted by a designer’s wishes or by his having to work with already prepared designs. His latest effort, given its official premiere on December 23, contains so much that’s insightful and charming, I’d like to say “third time lucky.” In truth, this production will take time to cohere.

Some points–beginning with what’s actually happening to the young heroine, Clara, in reality and in her imagination–need to be reconsidered and resolved. Other passages simply need further rehearsal and, more important, further performance to make them smoother and richer. And, if I had my way, the jokey stuff evidently put in to draw an audience of kids would also be toned down. None of its crass silliness–for example, the ballerina embodying the adult Clara playing peek-a-boo from the wings, as if animating her inner child–relates to the sophisticated sense of humor revealed in Ratmansky’s other ballets.

Surely there’s time for this fine-tuning to occur. ABT has an agreement with BAM to expand its Nutcracker season annually, over five years. Since The Nutcracker, in myriad permutations, has proved to be a sure-fire money-maker and the company needs to make good on its $5 million investment in the production, presumably all that’s necessary is patience and hard work. Of course the future holds one additional budget item: The many children in the cast will outgrow their roles in less than two years, requiring successors to be coached from scratch.

What sort of Nutcracker has Ratmansky given us? He’s positioned himself–comfortably, I think–between the old and the new. His version doesn’t have the look of fond loyalty to the past–to the original, choreographed in 1892 by Lev Ivanov, according to the plan formulated by Marius Petipa–yet it’s hardly a renegade version. Ratmansky has conceived his Nutcracker as the journey of a young girl who has not quite given up playing with dolls but has already begun to dream of romantic love (a little in fear, perhaps, of love’s erotic dimension).

What will we find different from the 1954 Balanchine version, which has held sway for more than five and a half decades? A clue to the answer lies in the fact that Ratmansky thought the party scene at the home of a comfortably off family too long and tedious. So he co-opted some of its music and contrived a cute kitchen scene to open his show and introduce many of the main characters, including those of the rodent persuasion. As a result, his party scene is superficial, without any subtext of relationships among the generations or of manners understood as morality.

My Hero! Catherine Hurlin (above), Tyler Maloney (below), and additional students from American Ballet Theatre’s Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School in Alexei Ratmansky’s The Nutcracker

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

The appearance of the strange Drosselmeyer (ostensibly Clara’s godfather, though the program doesn’t say so); Drosselmeyer’s gift to Clara of a doll-size Nutcracker; the jealous kid brother Fritz breaking it and Clara succoring it; the thrilling yet ominous transformation scene in which objects and living creatures change their relative size; the battle between the invading mice and the toy soldiers; and Drosselmeyer’s role as perpetrator of these dark wonders–none of this diverges inordinately from what we’re used to. Except that Ratmansky, with the best of socio-political motivations, makes Clara the one who brings down the nasty Mouse King, not just a helper in this surely justified assassination. Unfortunately this leaves the Nutcracker Boy (the shell-crunching toy now Clara’s size and human) looking like something of a wimp.

For the Snow scene, Ratmansky thought back to the real Russian winters he had experienced in his youth, where a driving storm could kill. He puts Clara and the Nutcracker Boy in real danger, then has Drosselmeyer rescue the shivering, disoriented children in a sleigh and guide them to the Land of Sweets.

Candyland turns out to be puzzling, sort of a Persian Paradise, with a Sugarplum Fairy who has a mere walking role: hostess-with-the-mostest. According to tradition, the wonders of this kingdom are presented in a series of self-contained dances evoking exotic domains from which goodies emanate. These are duly tackled, and Ratmansky has great fun with them, making a show of his cleverness to which you gradually succumb. The best of them is the hilarious “Arabians” (worthy of a PG rating, not that anyone paid any heed), a quintet for four voluptuous harem women and their “husband.” While the femmes, the irresistible epitome of Lust Lite, vie for the guy’s affections, they are a united in their assurance that his pompous attitude of power over them is ridiculous.

The “Waltz of the Flowers” is duly performed, but marred, I’d contend, by a quartet of male bees buzzing around all that irresistible pulchritude and daringly tossing every last bloom across a good bit of space from one “pollinator” to another. Perhaps only the traditional Dewdrop should be allowed to appear amongst the blossoms, because she complements them, her virtuosity lending sparkle to their lush romantic style.

The Snow scene of Act I was undermined in a similar way, with Ratmansky introducing a vision of a grown-up Clara and the Nutcracker Boy as Princess and Prince in the whitened forest just before the snowfall starts in earnest and then, taking a leaf out of Hans Christian Andersen’s book, has the snowflakes themselves torment the children. Both instances are clearly occasions in which a magnificent ensemble is meant to function alone, as a collective–and major–character in the ballet. It’s odd that Ratmansky, who has an ingenious gift for group patterning, should have put these obstacles in his way.

With This Ring: Gillian Murphy as Clara, The Princess, and David Hallberg as Nutcracker, The Prince

Photo: Gene Schiavone

To climax the delights produced in the Land of Sweets, the child visitors are finally treated to a full-blown vision of themselves as adults, who dance the grand pas de deux conventionally assigned to the Sugarplum Fairy and her Cavalier.

On the common philosophy that all good things must come to an end, Ratmansky gives us an epilogue that returns Clara to her bed back home, hoping he’s persuaded the audience to join Keats in wondering “Was it a vision, or a waking dream? / Fled is that music:–Do I wake or sleep?”

I’m willing to go along with the whole business provided that Ratmansky takes a long, calm look at what he’s created and makes some of the adjustments that will move his ballet above and beyond the category of Lively Entertainment. If he can’t or won’t, I’ll settle for being entertained–by his intelligence, his understanding of human nature, his knowledge and love of dance history, and his flair for the unexpected.

Children–some 30 of them at each performance–dominate the cast of this Nutcracker and they do themselves and their academy proud. They’re all students of ABT’S Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School and seemed more technically accomplished in this production than the pupils I last saw in one of the school’s demonstrations. Even more important for the occasion, they were natural and ebullient; some of them–Kai Monroe as Fritz, the naughty kid brother, and Justin Souriau-Levine as the Little Mouse, for instance–perform as if born for the stage.

As the Nutcracker Boy, Tyler Maloney evoked, perhaps inadvertently, some of the pathos of a youngster aiming for an authority that’s still beyond him. He was also inexplicably underserved by whoever coached him in the famous mime monologue in which he recounts his adventures-to-date upon his arrival with Clara in the Kingdom of Sweets.

The 14-year-old Catherine Hurlin, who is clearly the heroine of the show, was strangely perfect as the young Clara. Her movement was impeccably balletic when called for, unaffected and vivid at more pedestrian moments. Her every gesture and facial expression corresponded truthfully, phrase by phrase, to her character’s situation at the moment. Her teachers and coaches must have found her a phenomenon to work with. And yet, though I admired her performance, she never moved me. Everything she did, no matter how apt and beautifully executed, seemed to me taught rather than true.

As for the adult dancers . . . The grand pas de deux, originally for the Sugarplum Fairy and her Cavalier, complete with Sugarplum’s solo to the otherworldly music for the celesta, has, as I’ve said, been reassigned to a pair of characters called Clara, The Princess, and Nutcracker, The Prince. They are manifestations of the beautiful adults that the ballet’s child protagonists (young Clara, at least) dream of becoming when they grow up. Although their duet climaxes the ballet, with many a delicious rethinking of the traditional steps, as visions they somehow seem only belatedly relevant to the proceedings.

On opening night Gillian Murphy did quite well, considering the fact that the solo, in particular, doesn’t suit her greatest virtues–power, a star athlete’s exactitude, and a burgeoning dramatic gift. David Hallberg was in his element–a marvel of technical acumen operating with cool elegance. As for Drosselmeyer, the veteran dramatic dancer Victor Barbee still has to figure out who and what he wants this mysterious character to be.

Richard Hudson’s set designs and costumes play a significant role in the production–and often threaten to overwhelm it. While the chaste dresses for Clara and the other little girls at the Christmas Eve party are lovely, those for most of the inhabitants of the Persian Paradise that the Land of Sweets has become have more than a touch of Vegas about them. Granted, the brash colors and color combinations, aggressive patterns, and over-elaborate ornamentation are fun for a while. Eventually, though, they exhaust the eye and call to mind the taste of the nouveau riche.

The sets fare better, perhaps because they help tell the story. A front cloth, on view while the overture is played, shows a trim upper-middle-class house of yesteryear–tipped sideways to stand nonchalantly on one of its corners. The image indicates that what ensues will interlace prosaic reality and the realm of the imagination (and its accompanying dangers). As Tchaikovsky’s scene-setting music winds down, light pours through one of the upstairs windows. Then, at the party scene, a doll-house that replicates, three-dimensionally, the one painted on the front cloth is presented to Clara as a special Christmas gift. The closing passage of the ballet takes us inside the “real,” human-size house to the girl’s bedroom where, just behind the window we first saw illuminated, Clara now goes to sleep–secure and happy, cuddling her Nutcracker doll.

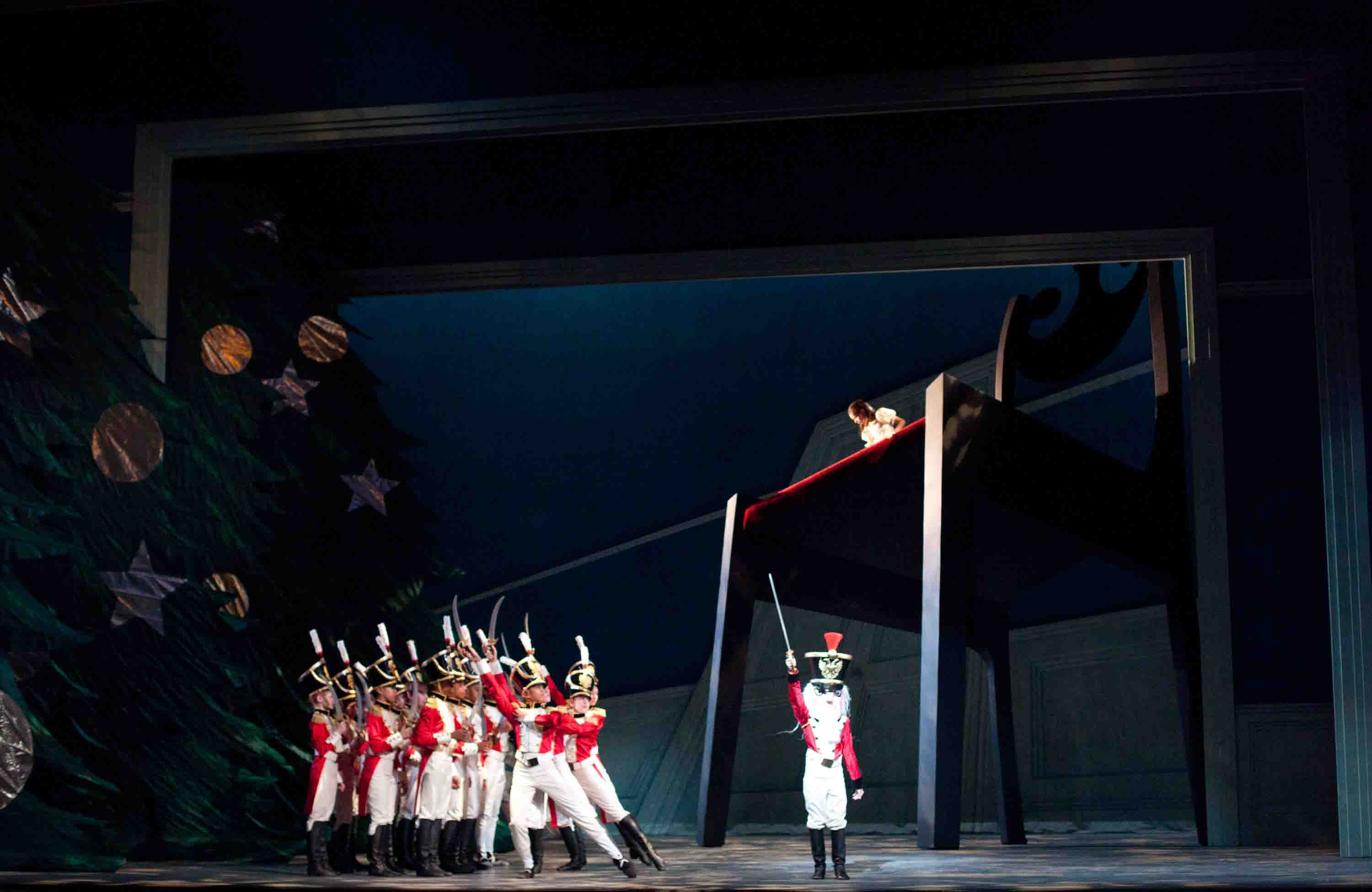

Another fine bit of scenic wonder arrives when–thanks to a magical transformation in size–a gargantuan chair appears. Perching on it, and looking down on the battle between the marauding mice and the toy soldiers marshaled by the Nutcracker Boy, Clara seems to be little more than a foot high. Nevertheless she goes from one anguished pose to another and, finally, removing one of her slippers and taking careful aim despite her distress, she exterminates the seven-headed Mouse King who is about to vanquish her beloved Nutcracker. The ominous look of the Brobdingnagian chair itself and the skewed perspective of this scene struck me as echoing a haunting modern-day children’s book by Chris Van Allsburg, The Mysteries of Harris Burdick. (To see the images in this book, click here. See–and click on to enlarge–the pictures for “Archie Smith, Boy Wonder,” “Missing in Venice,” “The Seven Chairs,” and, especially, “The House on Maple Street.”)

Two for the Show: Veronika Part as Clara, The Princess, and Marcelo Gomes as Nutcracker, The Prince

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Coda: I went back to BAM, despite the Holiday Blizzard of 2010, to see Veronika Part and Marcelo Gomes dance the leading grown-up roles. Gomes chose to be the recessive partner here. His technical prowess, delivered in his inimitable panther-on-the-prowl style, was present but subdued. Here, a man who can play villains and danseurs nobles alike was an ideal romantic suitor, his tenderness toward his ballerina providing a constant subtle support that made her look like a goddess.

Part was, quite simply, glorious. Dancing with the long, sensuous phrasing that suits her best, she even gave whiplash feats like supported multiple pirouettes a sensuous legato look (just as, a few minutes later, she would make the celesta solo aptly tiny and delicate, but still lusciously soft). Falling backwards from her prince’s embrace, she seemed to swoon. Towards the end of the adagio, a complexity of feelings appeared to swirl through her, as if she were recalling the emotions of the girl she once was and, despite natural reservations and fears, accepting the joys of womanhood.

Throughout this performance Part looked utterly confident, the self-doubt that has often plagued her banished. A Russian beauty with an air of high nobility, she even broke out from time to time into a genuine America’s Sweetheart smile. Performances like this make you believe that, despite the well-grounded warnings of the pessimists, ballet is not ready to die just now.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias

This is a very useful account [of Ratmansky’s “Nutcracker”] and, even when you approve of the result, there’s plenty of contrary evidence to ponder. Remembering, for example, the drag comedy of “The Bright Stream,” I’m not sure I can endorse your tribute to “the sophisticated sense of humor” in Ratmansky’s other ballets. (Your phrase “crass silliness” nails THAT experience for me.) But there’s so much detail and insight in your writing that I’m happy to allow you your Christmas spirit regarding the ballet as a whole. Best wishes for 2011.

Tobi, bless you, a brilliant, rich and I believe totally fair account of Ratmansky’s new “Nutcracker.” I was there yesterday (matinee) same cast you had seen earlier (David Hallberg and Gillian Murphy). I would love to see Marcelo Gomes and Veronika Part in it. Your choice of words brings the whole experience to a second life.

I hope Ratmansky takes/gets the time and inspiration to pay attention to each and every point/observation that you make.

I have been hoping that he is the next great choreographer in the ballet world, which is essentially starved for innovation and daring. There are possibilities within the new piece, but it straddles too many fences and suffers from the problems you’ve identified. Nice enough, but I want a lot more from him. I think he’s got lots more to give.

Happy New Year,

Jane

I enjoyed reading this very much – thank you! Best wishes for a wonderful New Year!

Tobi,

Your review is very rich and thought-provoking. I agree that this “Nutcracker” needs more work, but I also found it more satisfying than the Balanchine version I saw a few weeks ago. I found Balanchine’s first act boring — too much miming and, even though it revealed the relationships, nonetheless not really inspired.

Despite needing more work, Ratmansky’s “Nutcracker” has both formal and emotional elements that made it more interesting to me. One part of the emotional element is the way he choreographs the Prince and Clara’s wonderment at their love.

The formal element is how his “Nutcracker” is surprisingly cinematic, since Ratmansky uses references from film as well as dance history: the snowflakes look as though they’ve stepped out of a Busby Berkeley production. And his use of the young Clara and and her Prince simultaneously with the adult Clara and her Prince would work better with a cinematic dissolve. Indeed, I wondered if this was a conscious reference to the way Russian cinema developed the montage to carry forward the narrative both emotionally and visually. Some of this I realize he has already tried in earlier ballets such as “On the Dnieper.” Could it be perfected here?

So while I agree with your overall criticism that this “Nutcracker”

needs more work, the more I have talked about it and thought about it, the more I have found to like about it.

One question: I also don’t understand why in some versions the heroine is called Marie — who is the heroine of the actual E.T.A. Hoffmann story — and in other versions the heroine is named Clara (in the Hoffmann version a favorite doll in the doll cabinet). Perhaps you can explain.

Happy new year! I look forward to more thought-provoking reviews.

I went to BAM on the bad storm day to see Ratmansky’s “Nutcracker.” I love the dancers Hammoudi and Kajiwa as the adult Clara and Nutcracker Prince. He is in the corps and she is a soloist. I thought they were gorgeous together and can see a bright future for both. When Balanchine’s “Nutcracker” is ingrained in one for years and years, it’s difficult to allow another version to penetrate one’s brain. I know Ratmansky got a favorable review in the NY Times. As for me, I liked the choreography for the principals but hated other parts of it. I particularly hated the bees; I guess I just did not get it. At moments, I liked the choreography for the corps; at other times, no. Also disliked the fact that the kids playing the starring children’s roles–Clara and the Nutcracker Boy–were as old as they were. I would have preferred them to be a little younger, especially the girl.

Reading your review of Ratmansky’s “Nutcracker,” I was ruminating on—well, marveling at, really, but you will find that a hyperbolic word—your perceptiveness and descriptive powers. You explain so clearly both the ballet’s virtues and its flaws and give such a balanced and nuanced analysis of both. (I wasn’t able to see the ballet, as I was out of town for nearly the entire run, and your review was the only one I read that clearly delineated the goings-on.) I might add that your own understanding of human nature, and your ability to convey it in its full complexity, is one of the great pleasures of reading your reviews; your description of the emotional dimension of Veronika Part’s dancing was wonderful.

You have to love a critic who quotes Keats in a review of “The Nutcracker,” anyone’s “Nutcracker.” I join the earlier commenters above in their praise of the writing of this review, the insights into the ballet itself, and the epiphanies she provides regarding the dancing,–not easy to do about a non-verbal art form. But of course I’m not surprised. Tobi is an old hand, and a dab hand at insightful reviewing and we’re all very fortunate that ArtsJournal gives her the space for expansive, detailed, and if I may say so, artful writing.

Happy New Year, Tobi, and write on.