New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 22, 2011

Prayer: New York City Ballet principal dancer Wendy Whelan with SAB students in George Balanchine’s Mozartiana

Photo: Paul Kolnik

On January 22, the 107th anniversary of George Balanchine’s birth, the New York City Ballet marked the occasion with two programs, matinee and evening, composed entirely of the master’s work, along with supplementary activities that made the day a marathon of celebration. The doings were belatedly given the odious (and impertinent) title “Saturday at the Ballet with George”; I sense the work of the Marketing department here, but let that pass.

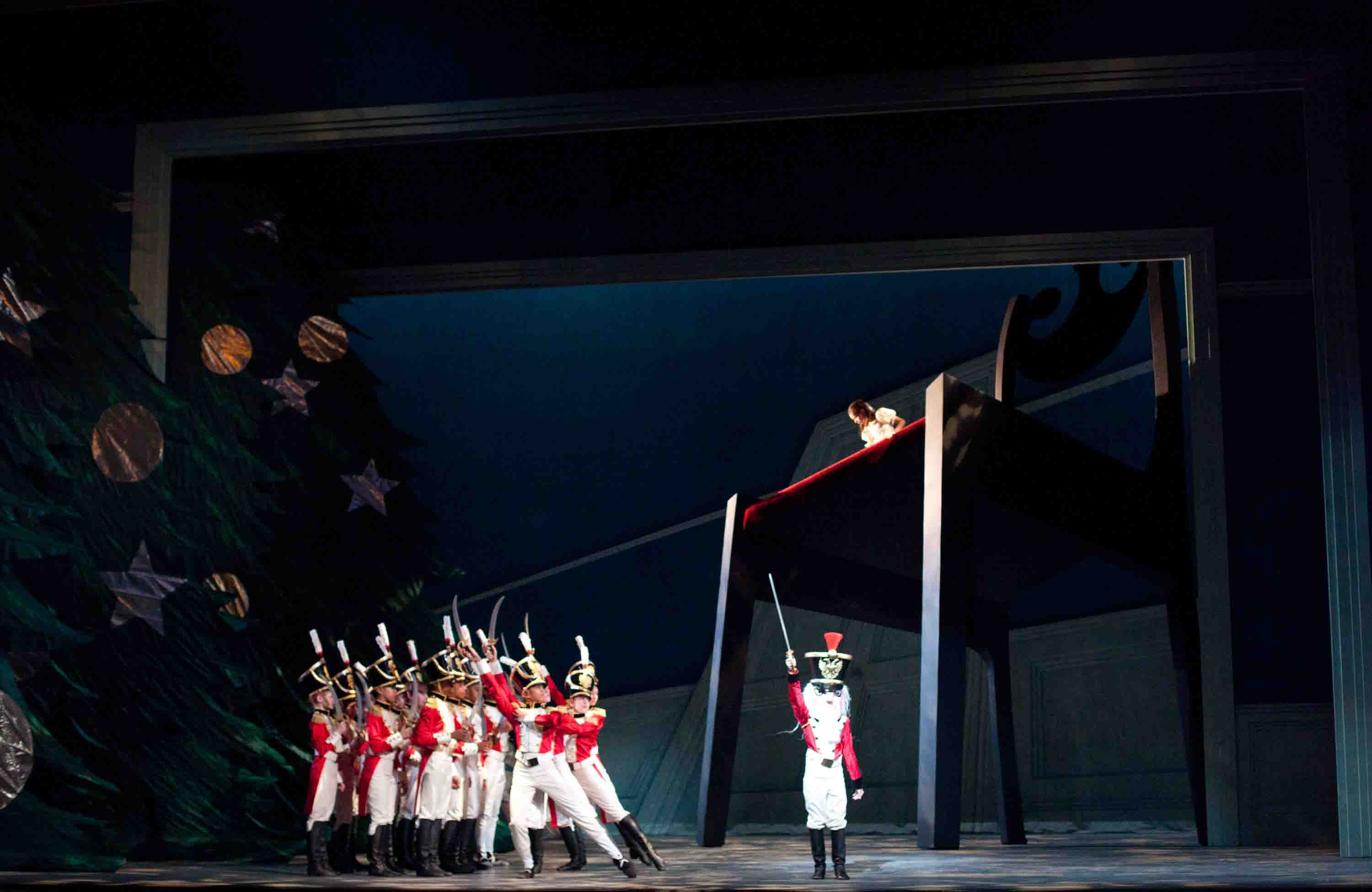

The works performed were: Walpurgisnacht Ballet, Duo Concertant, The Four Temperaments, Cortège Hongrois, Mozartiana, Prodigal Son, and Stars and Stripes. As anyone who follows the City Ballet’s seasons can tell you, these pieces were hardly chosen from a list of Balanchine’s greatest works ever, not even from Balanchine works recently in the company’s repertory, but–for practical reasons, I assume–from the pieces rehearsed for performance in the period immediately surrounding this ostensibly special event.

Prodigal Son (1929), The Four Temperaments (1946), and Mozartiana (1981; Balanchine’s last major ballet) are unassailable choices. Any one of them, standing alone, proves the maker’s genius. But a dozen others, at the very least, equal those achievements. Think Apollo (complete with the birth scene; 1928); Serenade (1935; Balanchine’s first ballet for American dancers); Concerto Barocco (1941); Symphony in C (1947); Divertimento No. 15 (1956); Agon (1957); Symphony in Three Movements (1972). And then there’s the 1960 Liebesleider Walzer. Admittedly it’s too long if you need to put at least three works on a program–unless you make one of the other pieces on the bill the eight-minute Monumentum pro Gesualdo (1960). Subtle and luminous, this brief ballet is one of my personal favorites. Every devoted Balanchine watcher will have his or her own.

Wrath: Teresa Reichlen, partnered by Jared Angle, in Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments

Photo: Paul Kolnik

What about the ballets we did see on the 22nd? On the whole–and this tells us a great deal about the current state of the company–the dances presented had been polished for accuracy. Hardly anything was slack, ragged, or performed with indifference, as has been the case too often in the recent past. The Four Temperaments, for example, positively gleamed with correctness. This very welcome improvement goes a long way; still it doesn’t take care of the subtler elements of dancing: profound musicality, sculptural and textural depth, hints of a subtext in presumably abstract ballets, a projection on the dancers’ part of what it is to be completely alive in the present moment. I may sound ungrateful for wanting so much, but a viewer whose memories of how Balanchine’s repertory looked when he still stood in the first wing at every performance, the most important scrutinizer in the house, is bound to compare today’s renditions to those of the past.

A persistent problem at City Ballet–and one that could be corrected–remained in evidence: casting against type. Take 4Ts again. Of the leaders of the main segments, only one was just right: Teresa Reichlen in “Choleric,” a long-limbed giantess whose fierce legs can set the stage on fire, while her tiny head remains poised, ever-alert.

Sébastien Marcovici, a seasoned, bulky-figured dancer with dramatic resonance in “real man” roles, was hardly the ideal choice for “Melancholic.” That section is usually awarded, rightly, to a lithe, vulnerable-looking fellow who’s immediately convincing–and appealing–as a weak-willed poetic type given to self-pity.

Jenny Somogyi and Jared Angle, as the “Sanguinic” pair that should anchor the ballet with serene classicism and confident optimism, were stolid in their exactitude. A video of their performance might well be a godsend to a person staging the ballet on a new cast, but the pair offered its immediate audience nothing beyond steps immaculately rendered. Amar Ramasar, at the peak of his power and absolutely glowing, is simply the antithesis of the “Phlegmatic” mood; he’s all grace and exultant joy, when he should be tying himself into knots.

On the whole the dancers of City Ballet, over 90 strong, provide endless fascination for witnesses to the trajectory of their careers. At every level of experience and ability, there is something going on. Take the following three, all easy to notice in the seven ballets danced on the 22nd.

America the Beautiful: Erica Pereira in Balanchine’s Stars and Stripes

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Erica Pereira, a soloist who unvaryingly shows enormous promise in the many challenging roles she’s assigned, is coming along well. Her purity of technique is amazing, yet there’s nothing mechanical about it. While she aces every single step with uncanny precision, she still makes each one look soft, even downy. There’s a calm about her, too, that contributes to her air of effortlessness.

Despite her gifts, Pereira still hasn’t come fully into her own. With her small, slender figure and sweet face, she looks like a child, and perhaps there’s something of an obedient and much-loved child in her dancing. She doesn’t yet dare to “own” the stage, to project out into the wider world from the spot assigned to her. She makes me think of a exquisite miniature displayed (and imprisoned) in a glass capsule.

I have great hopes for Pereira. I remember first seeing her, toward the end of her student days, rehearsing for SAB Workshop. She was to dance the female lead in Balanchine’s Square Dance. She finished a solo and waited for the ballet mistress’s corrections. There was nothing to correct except the dutiful look–stern and a little gloomy–that her face took on when she danced. “How about the smile?” teased the ballet mistress. Pereira smiled. It was like seeing Garbo laugh.

Georgina Pazcoguin has been noticeable in the company for some time, essentially as the latter-day equivalent of a character dancer. She’s been in her element, for instance, in Jerome Robbins’s Fancy Free, as the girl with the red shoulder bag–a foil for her lyrical chum who gets to do the romantic pas de deux. Radiating a personality that doesn’t take any nonsense, she carved out an identity as a feisty dancer, all vitality and edge. Lately, though, she’s being seen differently, “rediscovered,” as it were, as a classical dancer. On the 22nd she had demi-soloist roles in both Walpurgisnacht and 4Ts and acquitted herself beautifully, as if she’d temporarily blotted from her memory the dynamo she was as Anita, lashing the air with her red skirt in Robbins’s West Side Story Suite.

And then there’s Sara Mearns, a principal dancer who has acquired a huge following in the City Ballet audience. I think the public enjoys seeing an artist who dares to break the house rules of her profession or at least bend them to work with her unique gifts. Mearns’s plasticity, her abandon, and her ferocious power make me think of legendary stage presences like Isadora Duncan and yesteryear’s opera divas. It goes without saying that she shares their instinct for drama.

My Space: Sara Mearns in Balanchine’s Cortège Hongrois

Photo: Paul Kolnik

In Cortège Hongrois–one of Balanchine’s several spinoff’s from Petipa’s Raymonda–Mearns’s evocation of a generic princess suggests that the young woman in tutu and tiara encases a vulnerable heart in imperious postures and sculptural poses suggesting great metaphorical weight. Her big solo begins and ends with the same two moves–a firm clap of her hands followed on the next beat by one hand’s reaching behind her head, her elbow winged out, as her upper body arches proudly.

In between this phrase and its repetition, she seems to go through a troubled rumination on her duty as the ruler of her country, which is fatally incompatible with what she owes to her own pleasure in love. (Petipa had a narrative to help him; Balanchine had nothing but steps to music.) She appears to decide, courageously and firmly, in favor of the nation, but it’s not her choice that’s important. Rather, it’s the process of expressing thought and feeling through essentially abstract dancing that’s so thrilling. This is a Mearns specialty, and it’s one of the things that makes for the fans’ adulation. And mine.

“But first a school”: Peter Martins instructing students of the School of American Ballet

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The richest of the day’s supplementary events was the 50-minute condensed class Peter Martins gave onstage to a group of School of American Ballet pre-professionals. Ballet Master in Chief of City Ballet, Martins is also Artistic Director and Chairman of Faculty of SAB, the company’s feeder academy. The main thrust of the session was to reveal to the audience how and why City Ballet’s style, built on Balanchine’s precepts, is distinctive–as sharp and precise as a surgeon’s scalpel, charged with energy, and musically acute. Martins’s teaching manner, a suave mix of authority and humor, is clearly effective. I thought I already knew a lot about the subject, but I also learned a lot.

Dance followers had been asking one another right up until the day-long program began, if what we saw in the course of it would yield a true reading of the Balanchine repertory’s present condition at City Ballet. And what would that reading be? I thought of these questions again as I and my valiant companion for the day staggered in the bitter cold, eyes and minds flagging, to the Columbus Circle subway station. I didn’t ask them aloud because, as I realized, I haven’t yet come to terms with the fact that, with the choreographer gone, nothing is likely to compare with the performances I witnessed during his lifetime. This is not a complaint; this is simply a fact.

© 2011 Tobi Tobias