Mark Morris Dance Group: The Hard Nut / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Brooklyn, NY / December 10-19, 2010

For all the rigorously classical attributes of his work, Mark Morris, celebrated for his choreographic chops, has a distinct renegade streak. The Hard Nut, his version of The Nutcracker ballet, gives his iconoclastic outlook every opportunity to flourish. Morris’s take on the glorious Tchaikovsky score was created in 1991, when the Mark Morris Dance Group was in luxurious exile in Brussels, as the resident dance company of the Théâtre Royal de La Monnaie. A year later, when it was first performed in the States–where the custom of taking the kids to some version of the Yuletide treat had run rampant–it was seen as an antic response to the undisputed finest of traditional versions: George Balanchine’s.

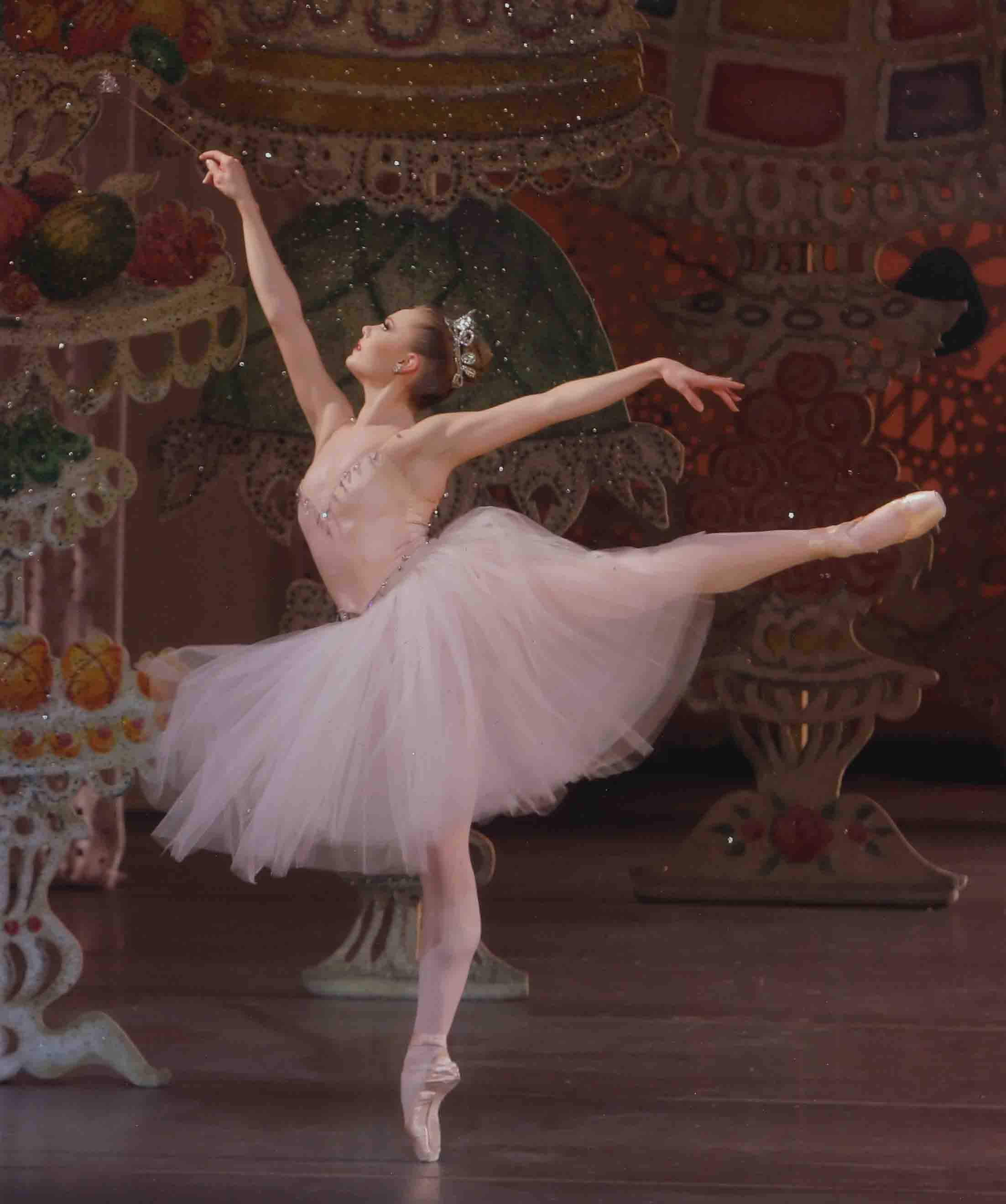

Christmas Eve Combat: Members of the Mark Morris Dance Group in The Hard Nut

Photo: Susana Millman

Time changes everything. Today, both committed ballet fans and folks who see, maybe, one dance performance a year, take The Hard Nut seriously. It’s no longer an amusing spoof (many viewers have never seen the ballet it’s thought to be spoofing). And it hasn’t merely become popular. It’s been admitted to the canon of works that have survived the time of their making and are expected to be seen again (and again) in the years to come. Like Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake, the show once considered a send-up has become a classic.

The Hard Nut certainly doesn’t stint on anything–except, of course, decorum. It uses the entire score Tchaikovsky composed for the original ballet choreographed for St. Petersburg’s Maryinsky Ballet in 1892 by Lev Ivanov (substituting for Marius Petipa who had fallen ill). And it includes the scariest part of the E.T.A. Hoffmann tale, The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, on which the original was based–and which most choreographers steer clear of for fear of marring a seemingly transcendent vision of Christmas joy. It probes further than any other Nutcracker ballet I’ve seen into the sexual subtext of the story, bringing out the sometimes fraught and always poignant passage from childhood to womanhood of the young heroine (the pre-pubescent Marie) and the enigmatic nature of the attraction the godfather figure (Herr Drosselmeier) has to the girl. (Is he a creator of benign magic for a child he adores or a latent pederast?) It revels in the outré and the absurd and sees youngsters for what they are–sometimes monsters, sometimes angels, most often quite ordinary souls, struggling and dreaming their way toward adulthood.

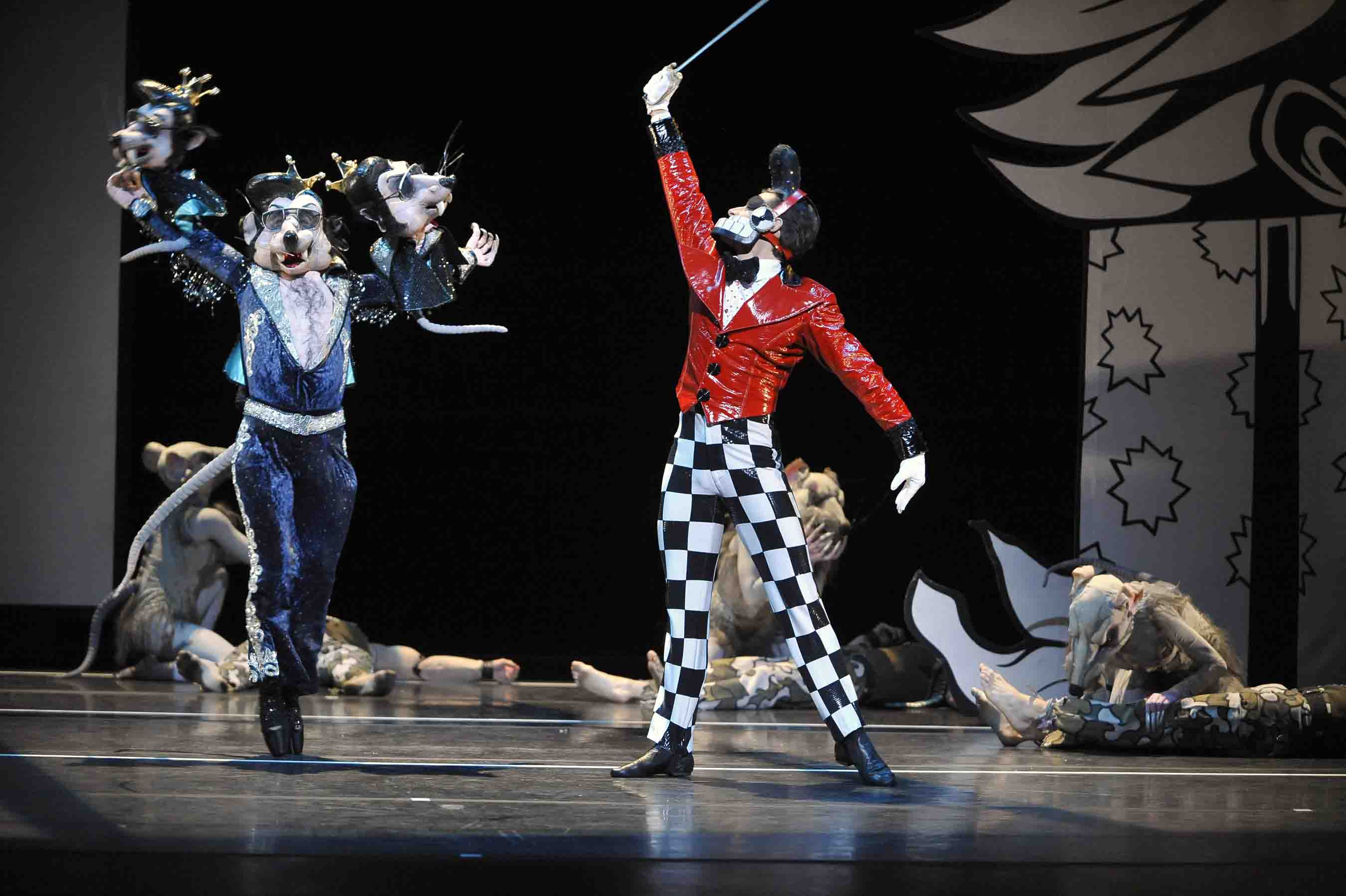

Morris sets his ballet in the American suburbia of the 1960s and ’70s, in the bosom of a family that gives new meaning to the word dysfunctional. Charles Burns, the distinctive comic-book artist who collaborated on the Hard Nut production, designed the adamantly sharp-edged, black and white world in which the ballet takes place. Uncompromising in revealing harsh truths, it’s undeniably stylish.

Party Time: Mark Morris and Amber Star Merkins

Photo: Stephanie Berger

The Christmas Eve party that opens the ballet reveals a nuclear family comprising a bumbling dad (now played by Morris himself, with terrific timing); a mom (John Heginbotham) who depends on alcohol and happy pills to sustain her futile aspiration to glamour; our heroine, the young Marie (Lauren Grant), still innocent enough to be dressed in frilly pink; her venomously adolescent older sister (Julie Worden); and her obstreperous brother, Fritz (June Omura).

And then there’s the maid (Kraig Patterson), who knows full well she’s not “just like family” and regards her employers with cynical resignation that fails to smother her sassiness. Patterson, a rail-thin black man with a ravishing back displayed by the plunging spineline of his/her costume, originated the role and has gotten better and better in it for two decades. His spidery pointe work–his character’s main method of navigation–is, alone, worth the price of admission. From the start it’s obvious that the casting of this show wasn’t hemmed in by gender conventions; rather, it’s enhanced by flouting them.

As for the “friends depicted within,” they’re about as crass and raunchy as can be without actually breaking the law, and right on top of the animal-inspired popular dances of the day.

Let me hustle you through the rest of the Act I plot. Drosselmeier presents Marie with a painted wooden nutcracker, which she adores on the spot. Fritz yanks it away and breaks it. Marie is heartbroken. The party guests leave. The family goes to bed. But Marie, now in her nightie (pink) with bunny slippers to match (trust the costume designer Martin Pakledinaz to get these things right!), re-appears in the living room to cuddle her injured toy. Sudden transformation: everything in the room becomes enormous. A colony of rats–larger and larger rats–appears, terrifying Marie. Nevertheless, she and her Nutcracker, aided by a bevy of G.I. Joes, vanquish the rodent enemies. The seven-headed rat king–every noggin crowned–lies slain, thanks to Marie’s alacrity with one of her slippers.

Rodent King vs. Nutcracker Prince: Utafumi Takemura and David Leventhal

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Now the girl lies unconscious–downstage, supine, legs splayed to reveal a crotch covered by pink ruffles–having fainted from her fright and her efforts. Center stage, there’s one of the simplest and most eloquent love pas de deux that ballet has to offer–for Drosselmeier and the Nutcracker, who has become human, even princely. (The house program calls him “Young Drosselmeier”; David Leventhal, the most exquisitely classical of the Morris dancers, is perfect in the role.) The love between the two men is partly the feeling of a parent or mentor towards a son, a nephew, or a protégé and partly erotic–though entirely tender, never lustful. It’s enormously moving, and acquires its full impact when, at the end of Act II, we see the young man repeat some of the moves he shared with Drosselmeier as he and Marie declare their first timid but increasingly ardent, love to each other.

That’s later, though. Just now Marie and her Nutcracker Prince venture into another, illusory, world whose way station is a wintry forest. Here, for the Snow scene, 22 dancers, male and female alike, wear the same costume, executed in a palette of white, black, and silver: bolero tops; short, audaciously bouncy tutus; and, in past performances, with some of the dancers in black pointe shoes and some barefoot. Their heads are sheathed in helmets studded with paillettes that catch the lights and beam out flashes so brief and tiny, you think you might be imagining them.

Stormy Weather: Members of the Mark Morris Dance Group

Photo: Catherine Ashmore

Each snowflake enters with fistfuls of white confetti, which she/he flings into the air, causing a mini-blizzard. Later, as the storm subsides into an eerie calm, the dancers travel horizontally, taking minuscule steps on tiptoe, arms outstretched to either side, dribbling “snow” from their fingers.

Visually magical, this representation of a snowstorm is playful, too, in its imaginative ingenuity. It’s exactly what you might have arranged as a child, co-opting your neighborhood buddies to put on a Winter Wonderland show. What’s more, activating your sense memory, it makes you recall the snowstorms that urged the kid you once were to run outdoors, exulting, as flakes got caught in your eyelashes or fell onto your extended tongue, melting just as you felt a small icy sting.

Naturally the steps Morris uses here belong to classical ballet’s whirling and leaping families (as contrasted with his shuffling, earthbound work for the Flowers of Act II, perhaps because flowers are, after all, bound to the earth). The intricate geometrical patterns Snow calls for are deftly handled and always satisfying, at once stimulating the eye with their intricacy and soothing the spirit with their orderliness. They take their place in the ever more complex chain forged by Ivanov and Petipa, Balanchine, and now Morris and Alexei Ratmansky.

At this point, it should be noted that Morris delights in pedestrian action as well as artificially wrought beauty. The Snow scene ends the first of the ballet’s two acts. During the intermission at BAM, the lush red stage curtain is raised about two feet so that the audience can watch the angular thrust of black-trousered lower legs coupled with the working end of brooms, as the stagehands sweep up the precious pale confetti for use in the next performance.

Don’t I Know You From Somewhere? Maid (Kraig Patterson), Dad (Mark Morris), and Mom (John Heginbotham) transformed in the Pirlipat episode

Photo: Stephanie Berger

Hoffmann tells it so perfectly–in a mood that’s simultaneously horrific, sardonic, and suggestive–that I wouldn’t think of trying to convey the Pirlipat story-within-a-story that launches Act II. Suffice it to say that Drosselmeier, on pain of death if he fails, is sent to find the hard nut (hence, Morris’s title) that’s essential to giving Marie and her Nutcracker Prince a happy ending. His search, taking him to one foreign clime after another, provides a logical excuse for the exotic divertissements in Act II.

Most important in this sequence of dances is, of course, the Waltz of the Flowers–a large-scale corps de ballet event that’s a cousin to the Snow scene. While the Snowflakes were creatures of the air, the Flowers are heavy, bent over the earth that sustains them, rooted, as it were. Among them is a soloist, flashing in and out of the matrices they form. This role, usually for a figure called Dewdrop and requiring scintillating technique, is none other than Marie’s mom (John Heginbotham, as you’ll recall), yet again pretending to a glory far beyond her temperament and gifts. Morris’s empathy for the character and Heginbotham’s subtle, layered portrayal combine to make your heart bleed even as you’re laughing at the lady’s absurdity.

The grand finale of The Hard Nut is an example of Morris’s devotion to community, which he regularly gives an importance equal to that of individuals. Here the young lovers, rejoicing in a happy fate after grave trials, is introduced and supported–indeed, animated–by everyone who has taken part in the story. Represented are family, friends of same, maid, anonymous flowers and snowflakes, dresser and furniture mover, even a delicate mouse princess from the Pirlipat section. They are all there, Morris has said in an interview, because “they helped.”

Happily Ever After? David Leventhal and Lauren Grant

Photo: Peter DaSilva

When the couple finally dances alone, their steps reveal them gradually losing their shyness when faced with real intimacy, and soon they kiss, and kiss again, and again. Even better yet, the two whisper into each other’s ear, telling secrets. Well with whom else would you wish to exchange secrets, if not your best friend? And who more worthy to be your companion as you walk away into a presumably blessed future? You may need a stalwart mate because, since you’ve turned your back to the audience, you don’t notice the mechanical rat with blazing red eyes that is scooting along behind you.

The Hard Nut ends its eight-performance run at BAM’s Howard Gilman Opera House on December 19. It will be followed by Alexei Ratmansky’s new version of The Nutcracker, for American Ballet Theatre, December 22 – January 2. Meanwhile, the National Ballet of Canada, which dances its own sumptuous Nutcracker in Toronto, is offering a tempting recipe for sugarplums.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias