Sasha Waltz & Guests: Gezeiten / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House / November 3-6, 2010

Three doors, phantasmagorically mismatched, open onto an empty room. The paint on its walls has peeled away in jagged fragments to reveal two previous colors. This derelict space could provide shelter only to the desperate. One of the doors has a thick brick frame that juts into the room. It’s easily imagined as the entrance to a crematorium; instantly you think Holocaust. It turns out that Sasha Waltz, who choreographed this dance-theater piece–Gezeiten (Tides), at BAM’s Howard Gilman Opera House, November 3-6–has been thinking about a more inclusive range of crises and catastrophes: 9/11, Katrina, earthquakes, tsunamis, genocide–all the disasters, natural and man-made, that the human flesh and spirit are heirs to.

Line-up: Sasha Waltz & Guests in Gezeiten

Photo: Richard Termine

Gezeiten is divided into three sections. The first is the most recognizable as dancing. Its mood is set by a man and woman who enter first, one body tightly behind the other, like sardines in a can. The pair paces the room cautiously, staring straight ahead, as the blind might. Other couples join them, replicating the first couple’s posture and gait, but soon the whole group flares out into bold motion, limbs partitioning the air, one partner propelling or cantilevering the other, exiting and reentering, then beginning to run–away from what? toward what? They toss each other’s bodies into the air with increasing vehemence. In between these wildly accelerating moves they return to order in a series of long line-ups. Rooted to the floor, they rise and sink in simple patterns. Pattern itself segues into the mechanical, then obsessive repetition of a single gesture. All the dancers flee but one, who remains in a slowly failing light, mindlessly reiterating the group’s last move.

Some of this material is accompanied by silence, some by fragments of Bach’s music for the cello, played by a man in a downstage corner, as if to remind us that bodies still able to respond to rhythm and melody by dancing retain some aspect of their humanity. Then the ambient sounds of war and destruction take over.

The second section is more literal, like silent film or naturalistic pantomime. The doors are now shut. Furniture has appeared–tables, chairs with screaming-red plastic upholstery as if from a cheap mid-20th century luncheonette, and a worn-out bed with an iron bedstead. The dancers–settlers in this closed camp–battle amongst themselves, then stack the furniture and climb onto its precarious safety. One guy becomes self-elected bully-in-chief, urging the mob to join in the abuse of his scapegoat, even after the helpless man has fallen. The agitated crowd gabbles in a cacophony of languages (the cast actually comes from many different lands). Another man starts tearing up the floorboards, eventually erecting four tombstone-like crosses on the site. A small woman hunched over a black pail–containing what?–sobs unremittingly. A woman in a white clinician’s coat tries to comfort her (in vain of course).

Lean: Sasha Waltz & Guests in Gezeiten

Photo: Richard Termine

The group quiets down, eats, drinks, forms a docile chorus to sing a little folk song sotto voce, then turns against its own members once again. Suddenly they’re besieged from outside–air-raid style sounds, smoke, darkness, fire–by a force against which their shelter proves inadequate. The fire shoots up in a single spiral, orange and yellow flames greedily rushing upward, apparently stealing all the available air. The fugitives collapse and vanish–except for the woman who grieved over the contents of the black bucket (the remains of her child, I guessed morbidly). As if finally accepting the inevitable, she puts herself to sleep on the worn-out mattress of the iron bed.

The third and last section of Gezeiten is a succession of surreal events that the spectator must interpret as s/he chooses. With the doors open again, “stuff” keeps on happening, in vignette after vignette. It’s well-nigh impossible to know what any of the events signify or how they relate to one another. The most solid item in this theater of the absurd has the floor boards mysteriously rising up at crazed angles and crashing down again, accompanied by hacking sounds, then darkness again, with quick-shifting beams of light ferreting out figures hunting god knows what, fleeing, or–justifiably, to be sure–going berserk.

It’s in this final section that you see why some dance observers believe Waltz has been influenced by the late Pina Bausch. The stage is full of Bauschian enigmas, Bauschian violence, even a sumptuous Bauschian evening dress or two (though not, as in Bausch’s earlier works, from the thrift shops, but more along designer lines, as in the later ones.) There are, moreover, Bauschian rivulets of water, spilling portentously and ludicrously from unlikely orifices. Lacking, alas, is the sense one had with Bausch (before she tamed her aesthetic) of a choreographer throwing caution to the winds as well as the wry Bauschian sense of humor.

Most significant, however, is the fact that all the strange visions Waltz conjures up lack theatrical power. One reason for this is that too many things are occurring at once, but the material itself just isn’t charged. I won’t bother you with details on the finale, dominated by some giant worms who had apparently inherited the earth; it was simply too silly.

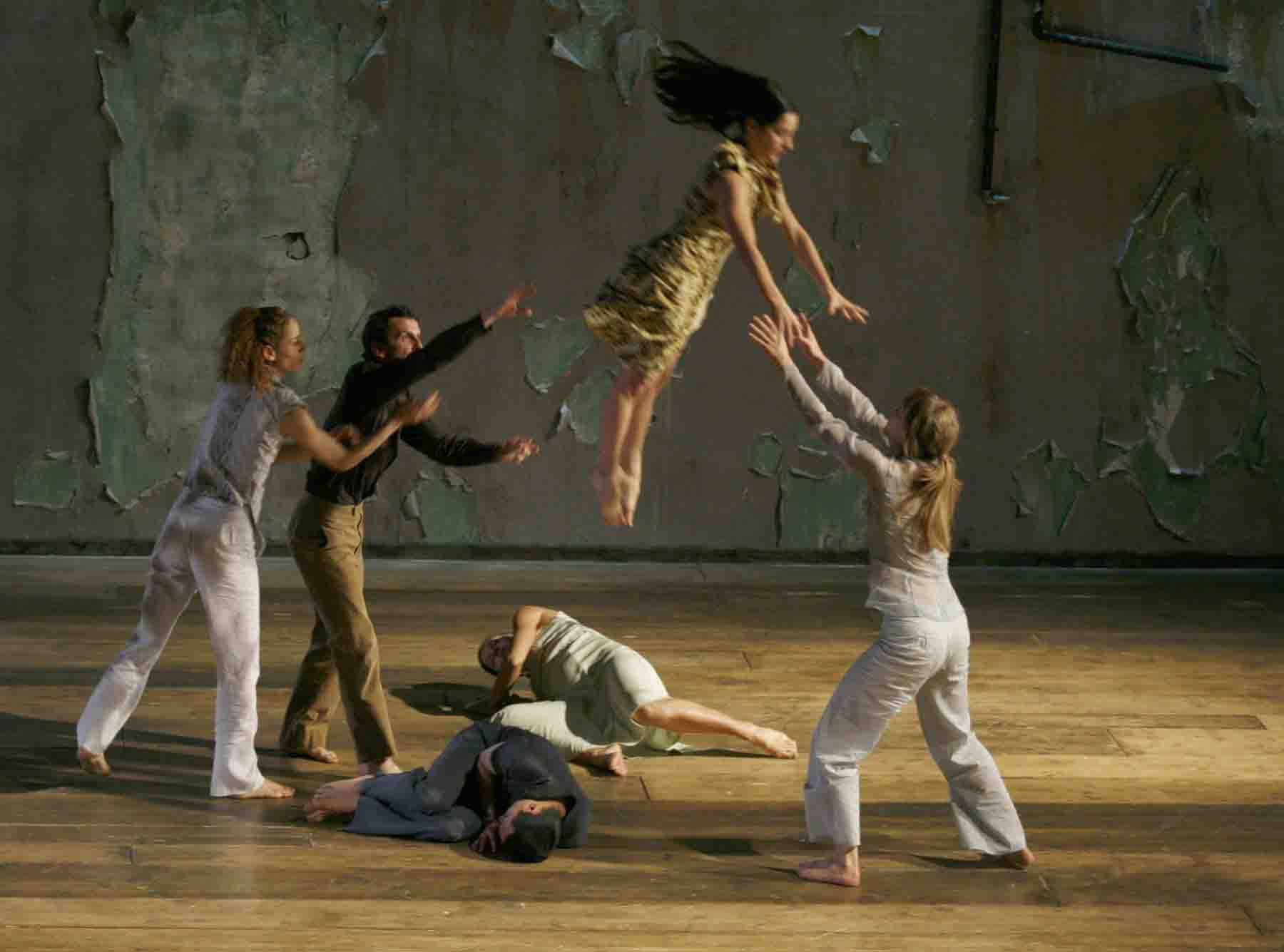

Trust: Sasha Waltz & Guests in Gezeiten

Photo: Gert Weigelt

I was interested in Gezeiten almost all of the time I was watching it–though nearly two hours of attention to work like this without any intermission is asking a lot of many viewers. Yet the more I thought about the piece afterward, the more I found it wanting. Most peculiar, I think, is the fact that the piece is not expressive. Events just happen, but the dancers–otherwise very deft and precise–project very little, if any, emotion about their plight. Sorrow, joy, rage, fear, and panic seem to have been excised from their vocabulary. Obviously they were carrying out the instructions they’d been given (perhaps along the lines of Balanchine’s “Don’t act dear; just do.”) But the Waltz who states in interviews that she’s charting the broad spectrum of people’s reactions to dire situations and who claims, moreover, that she’s illustrating the idea that reconstruction always follows destruction–that Sasha Waltz reads more eloquently than what is actually accomplished on her stage. Of course in Europe–Waltz is German and based in Berlin–program notes are considered an integral part of the show.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

“‘Gezeiten’ is divided into three sections,” you report. “The first is the most recognizable as dancing.” But in the end, is “Gezeiten” dance? Doesn’t seem so to me—not, at least, as you have characterized it.

Louis Torres, Co-Editor, Aristos (An Online Review of the Arts–www.aristos.org)

READERS: PLEASE SEE LOUIS TORRES’S COMMENT BELOW–AND FEEL FREE TO ADDRESS THE QUESTION YOURSELVES.

But is it dancing? The unanswerable question, particularly pertinent in the last half-century, I’d say. In “Gimme Shelter,” I characterize Sasha Waltz’s “Gezeiten” as “dance-theater,” though I don’t really care for labels. Knowing something about your work for Aristos, I think you’d be the perfect person to tell the readers of SEEING THINGS why “Gezeiten” may very well NOT qualify as dancing. Would you try to in under 250 words?

The first third of “Gezeiten” would be hard to characterize as anything other than dance: the choreography was American contact improvisation, slowed down, to imbue it with a soupcon of Weltschmerz. I would bet a sawbuck that the movement was created entirely by setting material from improv, perhaps with the help of video. The Germans have discovered contact improv! I thought. And only half a century after its invention! How–fresh!

The other two thirds of the work, which comprised mere behavior–not significant dramatic, choreographic action–more or less absurd, could be considered dance only according to the ubiquitous theory that “anything” can be considered dance if the creator wills it so. In a certain sense, this is tautologically, trivially true. But in fact, what the international institutionalized theatrical avant garde proves over and over again is not so much that “anything” can in be any meaningful sense made into or viewed as dancing, but that absolutely any stage activity at all–masturbating, staring at the audience for an hour, shitting in a bucket–can be successfully marketed as dance. Presuming, of course, that those doing the marketing are sufficiently cynical and indifferent to dance and choreographic values.

Here, an opportunity to say how I appreciate your writing — the fact of it, skill and humor and energy, and the breadth of it. Ideal.

I enjoyed reading your review, and I especially appreciate your concern over the poverty of emotional resonance in the dance work you described. I find that lack also in the visual arts department at the university at which I teach. A siphoning off of feeling. Things happen. Images appear. Many. Fast. Too many, and too fast. But they are so often devoid of anything that actually matters.

I was in Havana when Sasha Waltz presented her “Gezeiten” in New York and did not see the piece. But reading your review of it reminded me of an amusing episode in Berlin, when I attended the ISPA June 2000 “Congress.”

Berlin was then an exciting place, with Check-Point-Charlie gone and the no man’s land ready for the taking. West Germans had not yet turned against East Germans, and going from the Western sector to the East was like going back 50 years in time. Buildings on the East still had bullet-holes in them. The heat had hit 108 degrees. All factors provided for a very heady experience. Among the artists pushed by the German organizing agent for ISPA 2000 was Sasha Waltz, who had not yet been heard of in any significant way.

Before we arrived at Ms. Waltz’s domain, a panel discussion presented us with some statistics of the two different groups of Berlin artists — East and West. The panel included spokespeople from different arts groups from the two Berlins. Among them was Waltz’s manager and then husband, Joachim, who enumerated their hardships. Hardships such as being paid only 52 weeks a year and not 56, as some other dance companies were. Hardships such as having to look for their own dancers instead of being provided with them. Hardships such as having to start most things before the government would provide money and staff. Hardships such as having to look for collaborating artists! The crowning cry of despair was, “Can you imagine that we had to walk block by block for weeks to find our own rehearsal space! It was only then that the government was willing to pay the rent!”

As a choreographer attending as delegate I tried to be as unobtrusive as possible, but at that moment I let out a laugh that shocked everyone. It stopped the proceedings and everyone wanted to know what was behind that laugh. I had to say, “Well, where I come from, you don’t walk blocks for weeks, but boroughs for years to find your rehearsal space, and very few have their own. If they do, their lives are burdened by holding on to the space and paying the rent. The government never pays your rent. As to all the other hardships you experience: No company in my city pays 52 weeks a year, let alone 56. One of our most toured and beloved companies guarantees only 32 weeks a year (Paul Taylor’s), with salaries well under what a garbage collector earns. You have no idea what hardship is!”

Not being able to see my name tag, which said “USA,” many assumed I was referring to some backward city in Asia. When they were told it was New York City, everyone followed suit and howled.

When we did arrive at their domain, much was said again about how Waltz was a phoenix rising out of ashes, but I didn’t see that in her choreography. I did think, however, that born in East Berlin, with her excellent name, she would be perfect for the global performing arts field to push as the next “genius” from the EU.

Your article reminded me of what a panel, which included Yvonne Rainer, said at the recent program at Judson Church on the early post-modernists. The dancers and choreographers of that time and place did what they did, with nothing except the space and the want, the want for something different, something more, not something which already existed. In comparison, they lived at a time of such innocence that seems so precious now. Perhaps dance, like many other forms of art, has evolved out of innocence. Now competent and glitzy, influenced worldwide by the ten companies/choreographers highly supported by their governments in the last twenty years or so, even younger dance-makers feel that they have to use water, sand, rope, chairs, stairs, dummies, mummies, lipstick, slapstick, gowns (wedding gowns seem to be the rage at the moment) wind, scaffold, calligraphy, ponderous walk a la Robert Wilson (replete with robe) and, of course, all the electronics possible.

Perhaps one day the pendulum will swing back for dance to say something through movement without long program notes, without the big “idee,” with only the title to illuminate what movement and its organization can eloquently express, evoke, and inspire.

As always, reading your column brings me back to all that is wonderful about having spent decades in dance and encourages me to continue to seek inspiration quietly in my own work.

READERS: PLEASE SEE EXCHANGE OF COMMENTS BY TT AND LOUIS TORRES (NOV 7 & 8), BELOW. TT INVITED MR. TORRES TO COMMENT FURTHER. HERE IS HIS RESPONSE:

Does ‘Gezeiten’ qualify as dance (or art)? The answer must be No. It doesn’t make sense. That its first section is the “most recognizable” as dance isn’t enough. Furthermore, the second section includes no music to dance to (another essential ingredient of dance), just the group “sing[ing] a little folk song sotto voce.”. . . Of the final section, you observe that “it’s . . . impossible to know what any of the events signify or how they relate to one another.”

Is ‘Gezeiten’ “dance-theater” in the Pina Bausch vein, then, as you suggest? Perhaps, but that doesn’t make it art. In “Gimme Shelter” you refer to Bauschian “enigmas,” and you once called Bausch’s work “semi-inscrutable.” “Is it dancing?” you asked. “Sometimes the answer . . . must be a firm no.”

Bausch’s “extravaganzas certainly can’t be termed dance,” you also once declared. “They’re closer to theater. . . . They get . . . reviewed by the dance press because . . . theater critics refuse to be bothered with the stuff.” Dance critics should follow suit.

As you once observed, the now-classic tradition of modern dance honored “clear logical structure.” “In such work there may be subtlety . . . but there’s little ambiguity. . . . The world is knowable, and it makes sense, these dances tell us.” Well said. The same standard should apply to all work aspiring to the status of art.

(See “Avant-Garde Music and Dance,” Chapter 12 of ‘What Art Is: The Esthetic Theory of Ayn Rand,’ for full quotes and endnotes, and Aristos, for information on book.)

Louis Torres, Co-Editor, Aristos (An Online Review of the Arts)

Great reading, comments and all. I’ll have to come back.