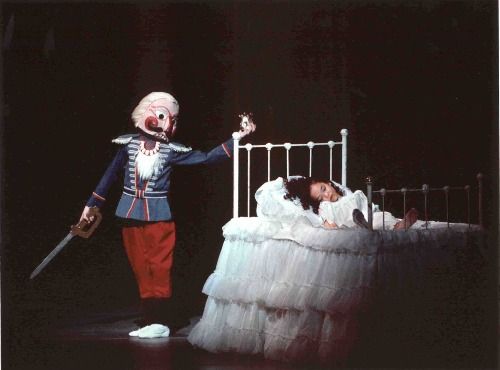

Dancer unidentified

Photo: Martha Swope (1964)

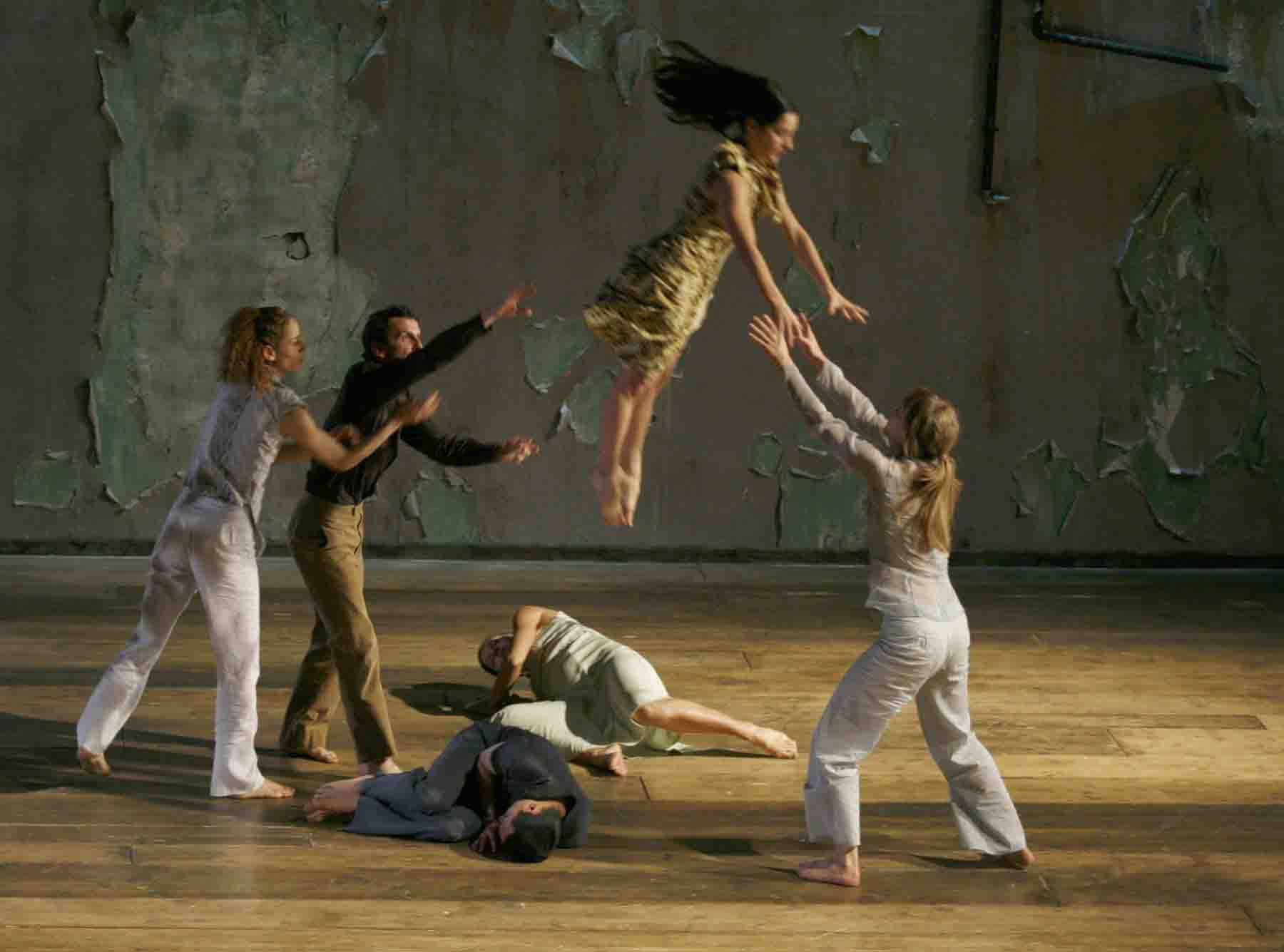

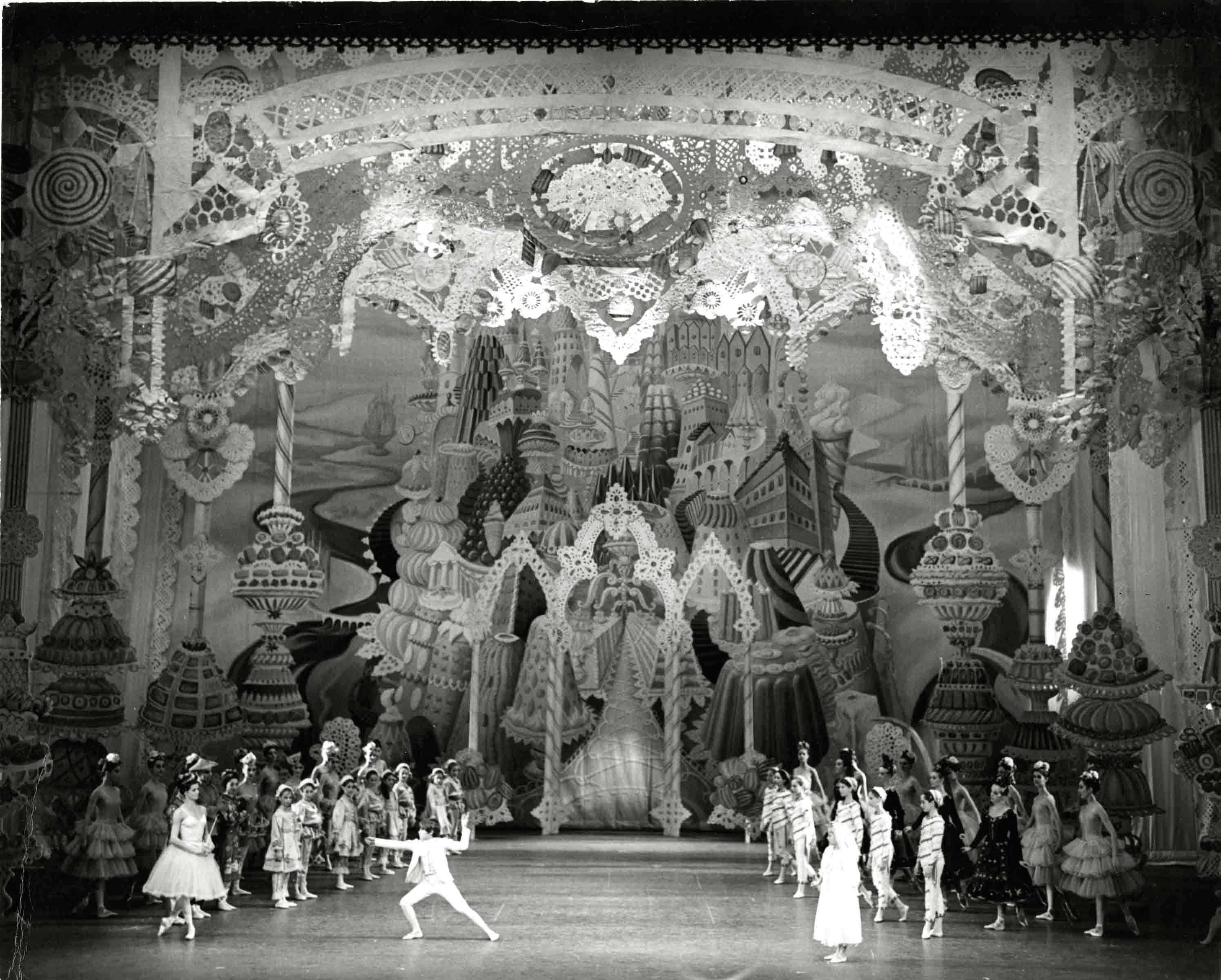

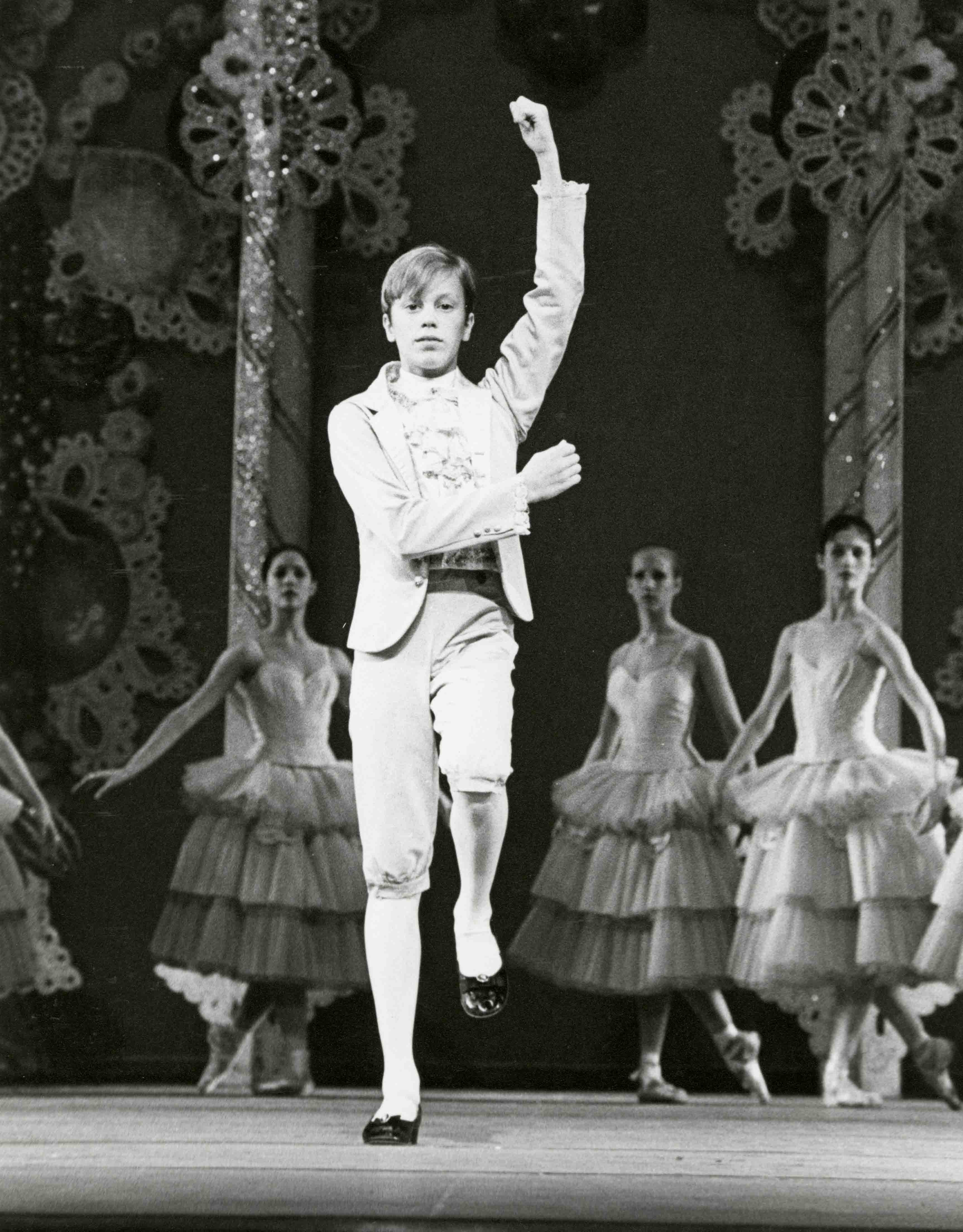

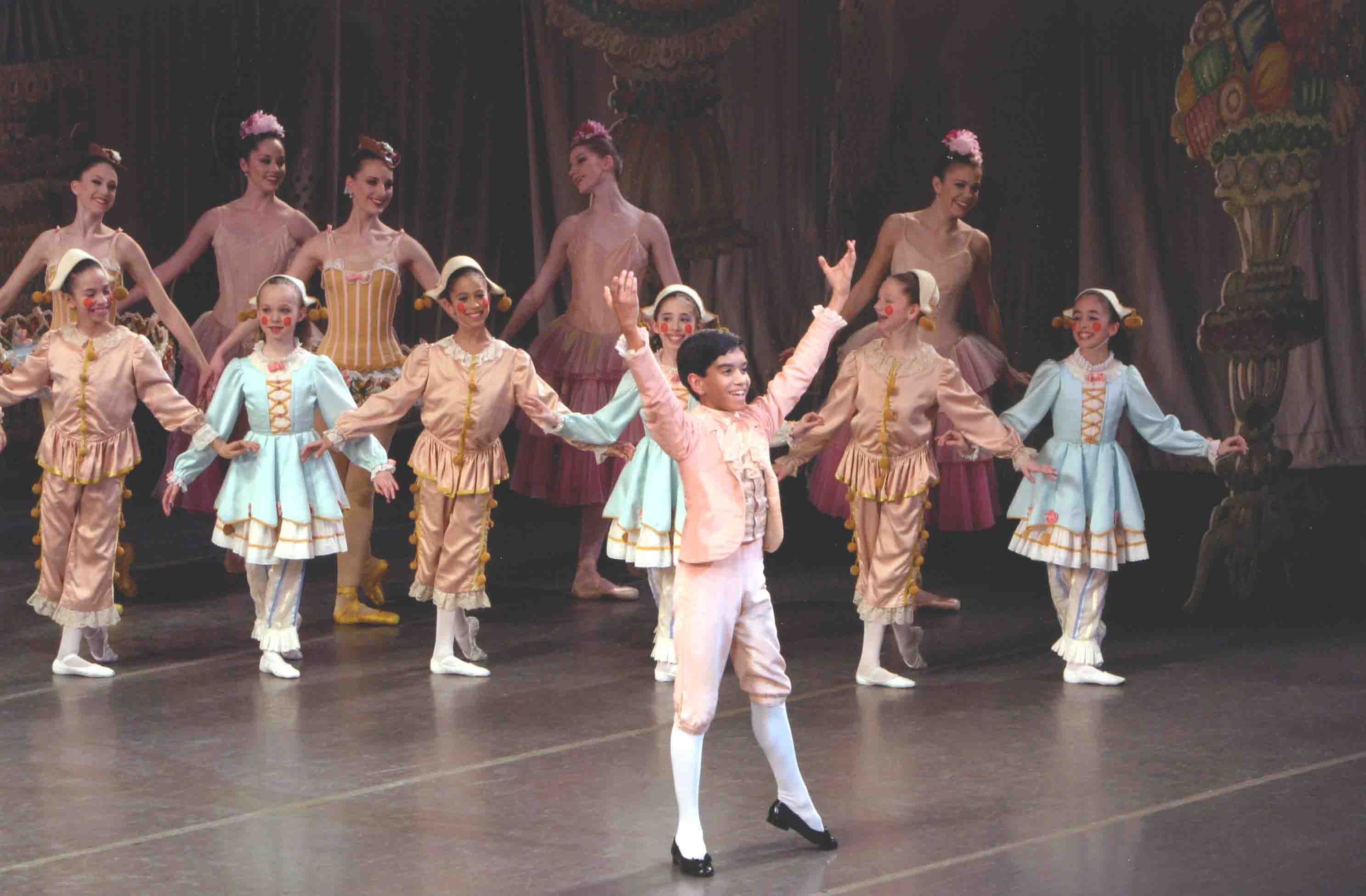

Note: The photos of the young Prince reproduced here are from George Balanchine’s celebrated version of The Nutcracker, inspired by the Russian production of his youth. Balanchine himself played the role as a student in the St. Petersburg academy that trained dancers for the celebrated company we now know as the Kirov or Maryinsky Ballet. Each photo shows the Prince in the mime monologue with which he tells the Sugar Plum Fairy about his earlier battle with the Mouse King and his retinue. Balanchine himself often coached the School of American Ballet student assigned the role.

Dancer: Christopher d’Amboise

Photo: Martha Swope (1972)

November’s rolling along toward December and the Winter Solstice, it’s already twilight by four o’clock, and the news of the world is not good. In these dark times (both literal and figurative), people–at least those who still have jobs and roofs over their heads–are inclined to indulge in frenzied bouts of shopping and preparations for gastronomic bravura as they anticipate “the holidays.”

Mercifully, the hectic tempo of the season is soothed now and then by seasonally appropriate thoughts–even deeds–of good will to all men (and women, of course) and by visions of an alternate world offered by theatrical performance. Here’s where The Nutcracker comes in, being a ballet that depicts Christmas in both its domestic and magical guise and lets us see it through childhood’s unfettered imagination.

Dancer: Peter Boal

Photo: Martha Swope (late 1970s)

Many a version of this venerable ballet exists, varying the era and the locale or culture of the original (Victorian period; upper-middle-class) or, more radically, changing the very concept of the work. The original Nutcracker ballet, created in Russia in 1892 by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, was based on E.T.A. Hoffmann’s intriguing tale The Nutcracker and the Mouse King (1816). Its music, commissioned from Tchaikovsky, is one of the Western world’s most evocative scores.

Dancer: Avi Scher

Photo: Paul Kolnik (1996)

Beginning with George Balanchine’s definitive version of The Nutcracker, choreographed for the New York City Ballet in 1954, the work has gradually become–at least in the States–an annual destination for holiday-minded viewers and a cash cow that saves the company producing it from financial ruin. People who couldn’t care less about ballet enjoy The Nutcracker; susceptible children are inspired by seeing it to clamor for dance lessons; and experts in the field never tire of mining outstanding productions of it for new sources of delight and new meanings. The most faithful Nutcracker viewer I’ve known, the late Edward Gorey, a notable author-artist with a pronounced penchant for classical dancing, told me that he attended every performance, year after year, of the City Ballet’s production, which typically runs for eight or nine performances a week, for five weeks.

Dancer: Gregory Malek-Jones

Photo: Paul Kolnik (2004)

In a four-part series under the umbrella title “Winter Solstice,” I’ll be writing about three of the many Nutcracker productions here in New York, one by one. There are several other local versions worth viewing–and I’ve seen some of them in previous years–but the ones I’ve chosen for this venture seem to me the ones likely to reach the widest audience. They are:

The Nutcracker / Choreographer: George Balanchine (1954) / New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center / November 26, 2010 – January 2, 2011

The Hard Nut / Choreographer: Mark Morris (1991) / Mark Morris Dance Group / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House / December 10 – 19

The Nutcracker / Choreographer: Alexei Ratmansky (world premiere) / American Ballet Theatre / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House / December 22, 2010 – January 2, 2011

Dancer: Lance Chantiles-Wertz

Photo: Paul Kolnik (2009)

Meanwhile, I offer below some of my earlier thoughts about the Balanchine Nutcracker.

THREE ARTICLES ON BALANCHINE’S NUTCRACKER:

The essay below was first posted on Voice of Dance, November 26, 2008.

Thoughts on Balanchine’s Nutcracker

New York City Ballet: George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker

New York State Theater, NYC

November 28, 2008 – January 3, 2009

New York City Ballet’s The Nutcracker with Robert La Fosse as Herr Drosselmeier. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

Yes, we–believers and doubters alike–take our children, grandchildren, and godchildren to see the New York City Ballet dance George Balanchine’s version of The Nutcracker, created in 1954 and an annual Christmastide event ever since. Many youngsters also dance in it, if they’re being trained at the School of American Ballet, the company’s rigorous academy. But this ballet is in no way mere kiddie fare. It offers the adult much food for thought–and reverie.

After Tchaikovsky’s celestial overture–during which we gaze at a front drop showing an angel spreading starlight over the snow-covered roofs of a gemütlich German town some 200 years ago–we get our first glimpse of a pair of children gazing with unquenchable curiosity at a world from which, for one good reason or other, they have been excluded. Marie and her rambunctious kid brother peer through the keyhole into the drawing room where their parents are putting the finishing touches on the massive candlelit Christmas tree and arranging the presents destined for the children and their young cousins and friends who are about to arrive. The firmly shut door means “Children, you may not look–yet.”

The ensuing party is a lively one, tamed by the grace of formal social dancing in which three generations join and the examples of civilized adult manners, along with friendly admonitions to over-boisterous youngsters. It harbors areas of mystery, too. They center on the presence of the elderly, eccentric Godfather Drosselmeier (accompanied by a solemn handsome nephew just a few years older than Marie and the rough-and-tumble boys at the festivities).

Drosselmeier seems capable of magical feats far more complex than the scarf tricks with which he first entertains the children. An ingenious inventor of mechanical toys, he has fashioned adult-size wind-up dolls and, especially for Marie, whose fancy it captures immediately, a foot-high working nutcracker in soldier’s garb. But then her overexcited, jealous little brother seizes it and dashes it to the floor so that its jaws, with their prominent teeth, can no longer crack nuts to deliver their sweet kernels.

When the party ends, as all parties must, and the guests have departed, Marie reappears in the deserted drawing room in her angelic nightclothes. She has left her bed to succor her beloved Nutcracker. The young girl–a tiny, fragile figure in the large, silent room–peers through its French windows at the wintry midnight townscape, but it is too dark to make anything out. It’s a lonely moment, and she comforts herself by curling up on the sofa, cradling her broken treasure.

School of American Ballet students in New York City Ballet’s The Nutcracker. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

Now vivid clues to more frightening, perhaps evil, aspects of life are introduced into Marie’s home–in which she is used to being cosseted with love, creature comforts, and safety–seemingly because the prepubescent girl is getting old enough to come face to face with a few threatening adult realities. Under the cover of night, Godfather Drosselmeier returns, mends the Nutcracker for the child he clearly adores, displays its face beside his own as if to point out a resemblance–and conjures up an army of mice.

More and more, as the decades have slipped by, the rodents–the king with seven heads, each crowned, his rodent family and friends, and a bevy of rodent offspring (a grotesque parallel to the human guests at the Christmas Eve party?)–have made the ensuing scene of the battle with the mice more comic than scary, a pity, I think; the balance was more effective when it went the opposite way.

Marie awakens to witness startling transformations. The Christmas tree grows to gargantuan size. The toy soldiers, neatly arranged in a case in the drawing room grow to her own height and come to life to battle the mice. The bed that Drosselmeier’s nephew earlier offered Marie for her broken Nutcracker magically scoots away as if of its own volition to be replaced by a life-size bed, and the Nutcracker, now grown as well, charges into battle to protect the terrified Marie. The changes of size and awakening to new powers hint at the physical and emotional processes of puberty, during which a child can seem to grow in body and soul overnight.

It is through the mice’s invasion, though, that Marie’s mettle is tested. The valiant Nutcracker is responsible for the necessary swordplay, but when it looks as if he may be defeated, Marie has the courage and the presence of mind to distract the Mouse King by throwing her slipper at him, so the prince can get the upper hand, slaughter the royal rodent, and hold aloft one of its seven golden crowns. (The boy will give Marie full credit for her bravery in recounting the event to the Sugar Plum Fairy in Act II–in a pantomime solo Balanchine himself performed as a ballet student at Russia’s renowned Maryinsky Theatre.)

Meanwhile, again as if by magic, the Nutcracker is stripped in the blink of an eye of his soldier outfit to reveal the elegant costume of a storybook princeling. With immaculate chivalry, he presents the tiny, gleaming crown to Marie and leads her out into the landscape she only peered at through the window earlier, it being imperceptible to her while she was a child sheltered in her own home. The scene they traverse is a forest swept by falling snow, with (human) snowflakes whirling through it, as if wafted by the wind. This is the realm of unmarred nature in which events once conjured up only by the imagination are now really about to take place.

At the Christmas party, we also witness Marie’s early lessons in love, first when she cuddles her Nutcracker while her little cousins and girlfriends rock the dolls they’ve received as presents, then when she solemnly shakes the hand of Drosselmeier’s nephew, to thank him for bringing her the miniature bed in which her injured Nutcracker can repose. Lastly, once the other guests have left for home, the boy escorted away by his uncle, the girl led off to bed in the opposite direction by her mother on a darkening stage, each of the youngsters extends a yearning arm toward the other, as if to promise that the bond beginning to form between them will not be broken.

New York City Ballet’s The Nutcracker. Photo by Paul Kolnik.

In Act II, when Marie and the Nutcracker Prince find themselves in the Kingdom of Sweets ruled over by the Sugar Plum Fairy, we’ve entered the domain of imagination given free rein. In one way it’s an homage to the ingenuous childish dream of possessing the full spectrum of deliciousness. In another, it contains a moral: the youngsters are being rewarded for mature, adroit behavior in their encounter with the marauding mice. Balanchine, as he said on another occasion, is having his cake and eating it.

Sweets from all corners of the universe are presented to the regally enthroned children and dance for them–candy canes, marzipan shepherdesses, hot chocolate–each according to its kind. Eventually, though, it’s time for Marie and her young prince to return to ordinary life, albeit in a magical sleigh pulled by reindeer that fly through the air. Imagination has been given its due and the youngsters have had their vision of pleasure which will no doubt sustain them throughout their lives, but there may be some relief, too, in returning to the familiarity of the commonplace.

Balanchine teaches many a lesson in The Nutcracker but doesn’t press any of them upon the spectator. They are simply there to be ferreted out or absorbed unconsciously, and all the more intriguing for that. For example, the choreographer uses children of different ages (giving each group dance material within its capabilities, which is then brilliantly executed), fully professional adult dancers of varying ranks, company apprentices in walk-ons, and a few senior artists in character roles. In this way, Balanchine shows how a dancer usually begins as an absurdly young child and then (if the will and the body hold fast and luck blesses the enterprise) progresses, stage by hard-worn stage, in his exacting trade.

Balanchine’s Nutcracker is also a treatise on the nature of reality and illusion–and a child’s uncanny ability to live in both worlds, moving fluidly between them. In the more rigidly compartmentalized adult world, this is a gift most often retained by artists.

© VoiceofDance.com 2008

The following piece was first posted on SEEING THINGS, November 27, 2003

A “Nutcracker” Anecdote

New York City Ballet: The Nutcracker / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / November 28, 2003 – January 4, 2004

The Nutcracker, in George Balanchine’s (for me) definitive version, danced by the New York City Ballet, opens November 28 at the New York State Theater for a run of six weeks. I know it well, not just as a dance critic but also as a one-time ballet mother whose School of American Ballet-attending child was for several years a member of the show’s huge cast of kids.

The Nutcracker, in George Balanchine’s (for me) definitive version, danced by the New York City Ballet, opens November 28 at the New York State Theater for a run of six weeks. I know it well, not just as a dance critic but also as a one-time ballet mother whose School of American Ballet-attending child was for several years a member of the show’s huge cast of kids.

In this latter guise–conveyer of child to endless rehearsals–I, along with the other moms, dads, and nannies, occasionally got to watch a stage run-through. I remember in particular a dress rehearsal supervised by Mr. B himself. Decades later, it still provides me with a clue to the great man’s sensibility. On this occasion, matters had worked around to the point where Marie, the ballet’s juvenile heroine, terrified by the attack of the predatory mice, flees to a white-ruffled bed, stands on it for a moment, all innocence and vulnerability in her little white nightdress, then tumbles backward in a faint.

Her fall looked fine, albeit a little smudged, to me, but Balanchine wasn’t satisfied. He asked that she repeat it and was no happier with the result. He went up to her and, with typical gentle courtesy, worked directly with her–quietly and intimately, as if the two of them were alone on the stage–explaining and showing what he wanted. Then he stood back as she tried again. It was still not right in Balanchine’s eyes. Turning from her so that she didn’t see his little twitch of impatience and exasperation, he addressed the children’s ballet master and the other assistants in attendance: “Somebody teach her how to faint.”

How to bow, how to faint, how to waltz. Over years of mere glimpses of Balanchine at work and many an interview with his dancers, I came to understand that these skills were as important to the choreographer as a breathtaking mastery of the classical dance vocabulary he did so much to advance. I think it disturbed him at the core when dancers (even child dancers, because they represented his art’s future) couldn’t execute convincingly the moves that any citizen of civilization can perform almost instinctively. Balanchine, as his work reveals, gloried in the high artifice of ballet, but he never divorced his art from human nature.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: George Balanchine’s Nutcracker

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

The following review was first posted in the Culture section of Bloomberg News, November 29, 2007.

City Ballet’s Annual ‘Nutcracker’ Defies Gravity

Robert La Fosse, standing second from the right, as Herr Drosselmeier, performs in the New York City Ballet production “The Nutcracker” in New York in this undated photo. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

Nov. 29 (Bloomberg) — A bracing tonic for the Scrooges among us is “The Nutcracker,” choreographed to Tchaikovsky’s captivating score by George Balanchine for the New York City Ballet.

In the course of its annual five-week run at the New York State Theater (this year, through Dec. 30), it regularly features the company’s seasoned stars as well as stars-in-the making; alternating casts of some 40 Lilliputian children from the School of American Ballet, impeccably rehearsed by Garielle Whittle; and scenic wonders such as a Christmas tree that grows to a surreal height, lights flickering.

You know the story: At a decorous Christmas Eve party long ago, Godfather Drosselmeier gives Marie, the prepubescent daughter of the house, a magical nutcracker that sets in motion striking transformations and wish fulfillments. These climax in a visit to the Sugar Plum Fairy, who reigns over the Land of Sweets, with Marie escorted by the nutcracker now transmuted into the young prince of her girlish dreams.

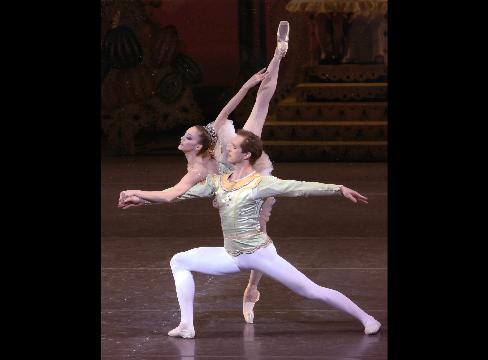

The opening night’s Sugar Plum Fairy, Maria Kowroski, mistress of adagio dancing, gave a ravishing account of the ballet’s climactic duet. Her Cavalier, Charles Askegard, was secure enough to toss her into the air for a moment midway through their fish-dive maneuver that is already a tour de force: “Look, Sugar, no hands!”

Maria Kowroski as the Sugar Plum Fairy, rear, and Charles Askegard as her Cavalier, perform in the New York City Ballet production “The Nutcracker” in New York in this undated photo. Photographer: Paul Kolnik/NYCB via Bloomberg News

More surprisingly, Kowroski was radiant and tender at her entrance, reigning over the flock of tiny angels that scoots across the stage in interweaving patterns as if on ball bearings.

Ashley Bouder, as the Dewdrop leaping and whirling her way through a corps of Flowers, was even more astounding than usual in her athletic brilliance. Audiences adore her. I still have reservations about her dancing, which is two-dimensional rather than sculptural, a phenomenon that a camera could render perfectly. Live dancing demands more depth.

I also miss the whiff of tragedy that Heather Watts once brought to this role, as if to reflect the evanescence of a dewdrop’s perfection. But perhaps that is too much to ask these days when bravura technique is valued above subtler qualities.

The generation of nascent ballerinas was represented by Erica Pereira and Rachel Piskin, not long out of their student years at SAB. They seconded the remarkable young virtuoso Daniel Ulbricht in the shamelessly politically incorrect pseudo-Chinese dance, “Tea,” which represents one of the treats displayed in the second act’s “Land of Sweets.”

Among the children in leading roles, Jonathan Alexander stood out for his spontaneous exuberance as the naughty kid brother. The all-important character role of Herr Drosselmeier lies at the other end of the age scale. Playing the enigmatic inventor and magician who makes Marie’s dreams (as well as the nightmares) come true, Robert La Fosse has toned down his earlier over-the-top interpretation. Now he displays just the right blending of strangeness and fantasy.

Through Dec. 30 at the New York State Theater, Lincoln Center. Information: +1-212-870-5570; http://www.nycballet.com.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved.