Kidd Pivot Frankfurt RM: Crystal Pite’s Dark Matters / Alexander Kasser Theater, Montclair State University, Montclair, New Jersey / October 21-24, 2010

Name Crystal Pite and most of the dance enthusiasts I know still say “Who?” Maybe it’s just America that doesn’t know her. Yet. Pite’s had a solid career as a dancer–in her native Canada and beyond, notably with William Forsythe, in Germany. Turned choreographer, she’s created pieces for companies of some rank, among them Nederlands Dans Theater, Ballett Frankfurt, and Les Ballets Jazz de Montréal. She now has her own troupe–Kidd Pivot Frankfurt RM.

I first saw Pite’s work in New York when Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet performed her Ten Duets on a Theme of Rescue. Amidst a familiar crop of would-be chic, portentous, hollow works (beautifully danced, mind you), it made its mark. Abstract with an emotional subtext, it was meaningful as I watched, and proved to linger in my memory. So off I went to New Jersey to see Pite’s program-length Dark Matters, part of the Peak Performances series at the Alexander Kasser Theater, on the campus of Montclair State University. NIMBY, you might say.

“We work in the dark . . . “: Crystal Pite’s Dark Matters, for Kidd Pivot Frankfurt RM

Photo: Dean Buscher

Quotation: Henry James

Dark Matters (the latter word can be taken as noun, verb, or both) has two parts, separated by an intermission. The first half is bound to charm everyone. Performed by itself, it would be perfect for the New Victory Theater, which deals in productions for children that won’t drive the sophisticated adults escorting them to thoughts of infanticide due to the boredom or revulsion that crude or stupid “kiddie” shows arouse in them.

Our first glimpse at the rise of the curtain is, indeed, darkness. Then scanning beams of light–as if from a detective’s flashlight or searchlights from the roof of a prison, thwarting escapes–pick out segments of a poky pre-modern study where an Inventor (let’s call him) works, obsessively intent on his latest project. The scene is simply rendered by Jay Gower Taylor, yet it’s redolent of Dickens, or maybe Edgar Allen Poe, or then again E.T.A. Hoffmann, whose tale The Sandman inspired the libretto for the ballet Coppélia.

With a steadier if still dusky light we see that the Inventor is fashioning a mannequin with articulated joints–a cousin to the ones artists use for anatomical drawings. A quartet of puppeteers appears–or were they always there, in the shadows?–to manipulate the finished figure with miraculous exactitude. As in traditional Japanese theater, these facilitators are completely shrouded in black; even their faces are veiled. They huddle together, wielding long wands with strings that attach to the delicately built miniature man. Self-obliterating, they nearly convince the viewer that the Inventor is teaching the mannequin to walk, each stage of that difficult, glorious process exquisitely defined.

But many an inventor has seen his creation get out of hand and turn on him in close-to-human guise, lacking nothing but a soul. Literature loves the theme: Think of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Think of Frankenstein. Think of Hoffmann’s Automata as well as The Sandman. As soon as it can walk fluidly, the Inventor’s mannequin begins to display feelings–first hurt, then annoyance, then rage against its creator. Its attacks grow increasingly violent until they wreck the room and then the man himself. Both are left lying inert–motionless, unconscious–in exactly the same position on the workroom floor.

To this old theme, usually filed under the rubric of (entertaining) horror, Pite adds the dimension of humor. She makes the whole process of science usurping God’s role as creator-in-chief funny–funny in the best way, which involves magic, irony, and a definite vein of the tragic.

Ties That Bind: Kidd Pivot Dancers in Pite’s Dark Matters

Photo: Dean Buscher

The second half of Dark Matters is ostensibly an abstract version of the first half. And indeed certain moves in Part One are repeated in Part Two, like dutiful reminders of the preceding narrative. Overall, though, the movement is hit-the-mark precise and extraordinarily powerful, the energy emanating surprisingly from shifting zones of the body. You wouldn’t want to get in its way.

Solos seem to make statements, though you’d be hard put to name their various topics. Group passages, which owe a lot to contact improvisation, emphasize twining and cantilevering. But, sad to say, despite the dancers’ whiplash power, most of this half is not as engaging as what came before. It goes on too long, too, making us all the more aware of our disappointment. This section is redeemed in a way–and the whole piece unified–by a final, contrastingly tender, passage in which the slight, graceful man who played the Inventor gently solaces and supports a woman almost stripped to the skin, helps her flex her knees and ankles and–yes–walk. Together they manage a slow, quiet duet of mutual aid and mutual commitment, which is, perhaps, as close as post-modernism can get to love.

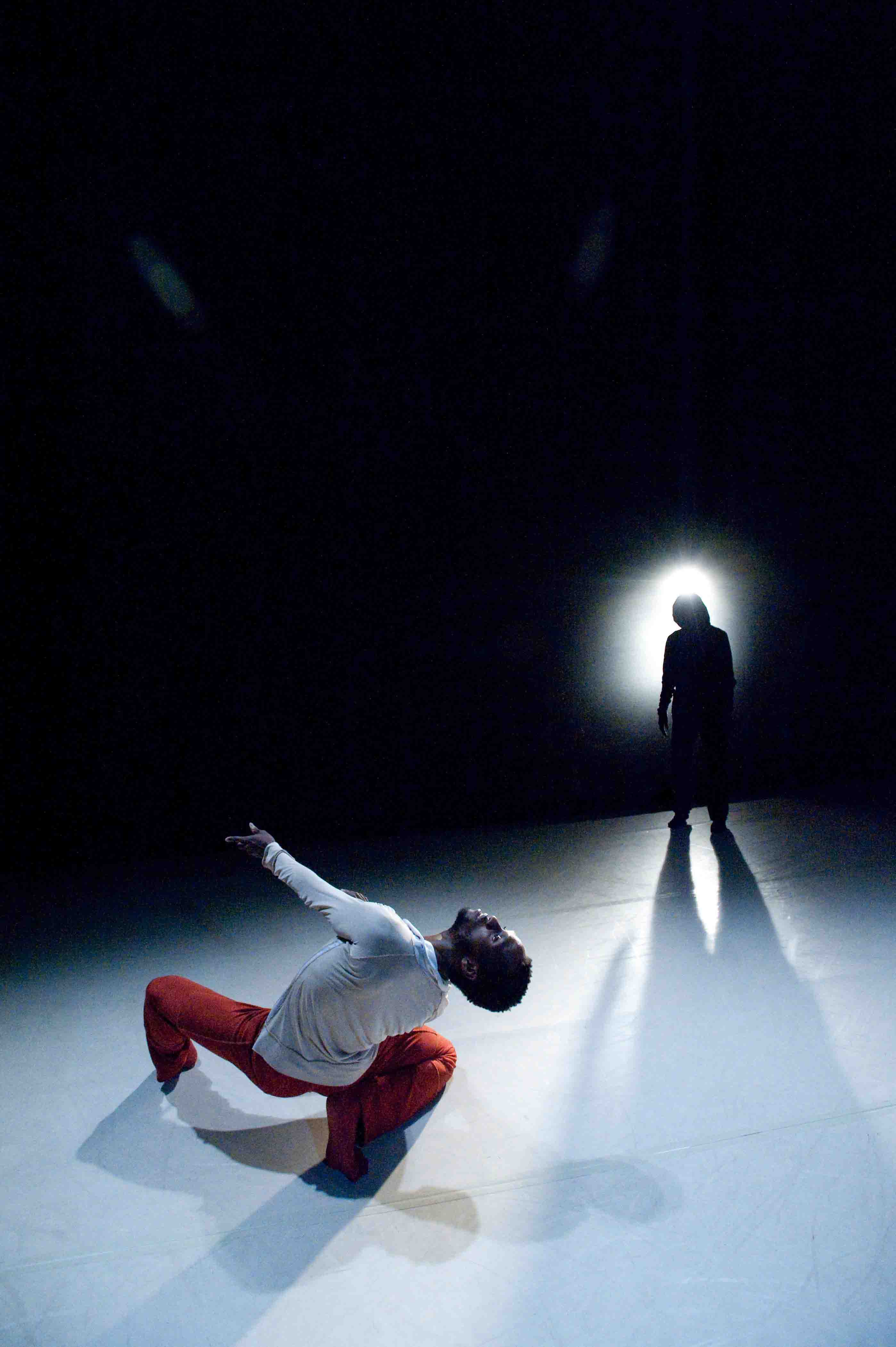

“Our doubt is our passion . . .”: Jermaine Maurice Spivey in Pite’s

Dark Matters

Photo: Dean Buscher

Quotation: Henry James

In interviews and in a personal statement from Pite tucked into the press kit, the ultra-brainy choreographer talks about scientists’ concept of “dark matter.” It’s a force, they claim, that makes up a goodly portion of the universe. However, they can only infer its existence and nature; as yet they have no absolute proof. According to Pite, the doubt that haunts this theory parallels a dance-maker’s (i.e., her own) “not knowing” about her creations, which causes her to work in a state of agony, and so forth. She even quotes the playwright John Patrick Shanley in her program notes: “Doubt requires more courage than conviction does, and more energy; because conviction is a resting place and doubt is . . . a passionate exercise.” We don’t need to know all this; Pite’s piece speaks for itself–and positively about her future.

The audience for Pite’s opening night by no means filled the house, but it was certainly enthusiastic. More than half of the viewers were young people whom I took to be Montclair State students. This largely local crowd made me wonder how much of the NYC audience Montclair could attract on a regular basis. The Brooklyn Academy of Music finally persuaded Manhattanites that they could cross the river for art’s sake, but BAM was accessible by public transportation within the MetroCard zone. For NYC dwellers, who are often car-less, Montclair is still a stretch–as much mental as geographical.

The Kasser Theater is accessible by charter bus from the Port Authority Bus Terminal on weekends and by a NJ Transit line from Penn Station on weekdays. The travel cost is rock bottom as are tickets to the shows. Still, why bother, when Manhattan (with some help from BAM) is still the dance capital of (at least) America? I’ll tell you why: For several seasons now, Jedediah Wheeler, executive director of the Kasser’s arts and cultural programming, has exercised his sense of what’s unique and worthy to choose forward-looking choreography that honestly deserves that description.

Granted, if you’re a New York dweller, the Kasser is not a mere twenty minutes away from your hearth. But surely you can count the travel time as a little vacation from the hubbub of urban life and chat with your seat mate, do those deep-breathing exercises meant to relieve your stress, read, or simply dream. When you arrive, inhale slowly; the air is amazingly fresh.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

![IMG_5744[1].jpg](http://www.artsjournal.com/tobias/IMG_5744%5B1%5D.jpg)