Every once in so often, a friend or colleague asks to read the manuscript of a children’s book I’ve written and am trying to place, The (True) Life Story of a Dancing Cat. A number of these readers subsequently report that the story made them cry in the subway. Although I’ve published over two dozen books for young people, this is the only fiction that deals with dancing (my more visible beat). It has been sold three times and each time–talk about bad luck!–catastrophe kept it from being published, though I was allowed to keep the advance twice (some indication, I assume, that the publishing powers find it worthy). Equally relevant, I still believe in this book–it makes people cry in the subway, for goodness sake!–and am still trying to find the right home for it.

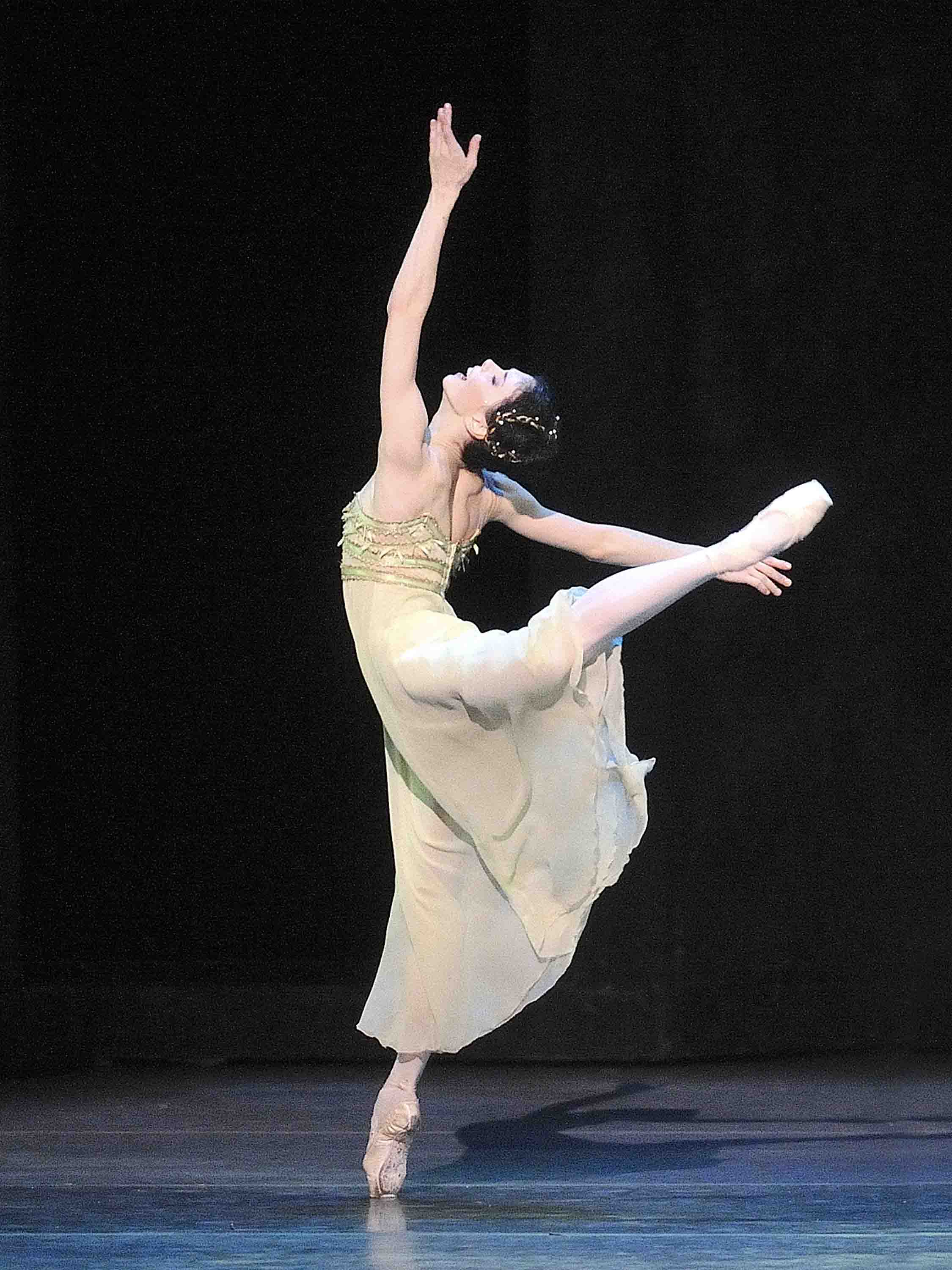

Aside: This is how the underground crying comes about: The absurdly busy New Yorker grabs the daily sheaf of mail (yesterday’s, since delivery is chronically late) out of her all too tiny metal mail box as she leaves her all too tiny apartment for duties and adventures in the Great World. She leafs through it rapidly on her walk to the subway, culling the ads and catalogues and depositing them en route in a public trash bin. (I’m told this is illegal.) Then, once entrained, she reads the few pieces she cares about. I like to think that Sylvie (as my story is informally called, after the name of its feline heroine) makes the reader weep–in public, in a hellhole like the New York subway system!–because it conveys the poignancy of a life in dance, with its ecstatic moments, its inevitable heart-breaking ones, and the vision of beauty and intense feeling that fuels a dedicated artist’s unswerving pursuit of her or his trade.

Surely most of you reading this right now are familiar with being reduced (or is it elevated?) to tears by a passage in a ballet–not just once, but every time you see it. One of these, for me, occurs in the wedding scene that closes August Bournonville’s A Folk Tale. Here, after overcoming all sorts of threatening medieval magic, the fresh young lovers are united in a surround of innocence and rose petals, each modestly claiming himself or herself unworthy of the other. The dulcet purity of this scene and its prevailing gentleness are utterly persuasive. No wonder that, even today, Niels W. Gade’s Wedding Waltz from the ballet’s score opens the dancing at Danish marriage celebrations.

The same moving identification may be true for you with bits of poems, novels, and plays. For certain paintings–like Rembrandt’s self-portraits from his spirited youth to the year of his death at 63, when his face seems to have crumbled from decades of piercing evocations of human bodies and souls. For films that go deep. I remember that, years ago in New York, two festivals of films by the incomparably subtle Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu ran simultaneously in New York. People I knew seemed to go to these screenings every day, as I did. When the lights went up at the end of the films, there they were–highbrow artists and intellectuals–unabashedly mopping up the tears streaming down their cheeks.

I believe that these tears have nothing to do with personal sentiment. Yes, they are personal, but they are not sentimental. They are the result of a work of art’s touching your personality, expressing something central to you that you, perhaps, thought hidden or embarrassingly unique, and setting it forth with gorgeous clarity, delicacy, and intensity for all the world to revel in. In a sense your tears are the tears of thankful recognition.

Of course some works will move you beyond the realm of tears–art that makes an unarguable statement, written as it were in stone, to which we must all accede, about the nature of human experience and the architecture of the universe in which it takes place. The Giotto frescos in a small church in Padua, say. Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco and Graham’s Primitive Mysteries. Passages in King Lear that relentlessly increase in intensity as the reader ages. Scenes from the work of the towering nineteenth-century Russian writers–Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Chekhov–in response to which one can only bow one’s head and say yes. But that is a subject for another day.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias