Ballet Diary No. 7: New York City Ballet: Philip Neal Farewell; Albert Evans Farewell (NYCB’s season runs through June 27 at the David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC); American Ballet Theatre: The Sleeping Beauty, with Alina Cojocaru and Natalia Osipova as Aurora (ABT’s season runs through July 10 at the Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC)

Note: This is No. 7 in the series “Ballet Diary”–comments on the 2010 spring seasons of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, along with related performances. To read previous pieces in the series, click here: No. 1; No. 2; No. 3; No. 4; No. 5; No. 6. The completed “Ballet Diary” series will comprise nine essays.

Until a final solo bow on the flower-strewn stage of the David H. Koch Theatre ended his exquisite farewell performance with New York City Ballet on June 13, if you wanted to see the term danseur noble illustrated in the flesh, you could watch Philip Neal.

One Last Time: NYCB’s Philip Neal and Jenifer Ringer in Balanchine’s Serenade

Photo: Paul Kolnik

In his 22 years with the company, Neal was the model of the quiet authority that is earned through purity. His technique had a clarity that seemed to be bred in his bones. His demeanor was modestly reserved; he often seemed to disappear into the dance and was obviously unacquainted with the realm of “show biz.” He cultivated “the plain style”–without excluding grace and elegance. This was evident even in small things: The movement of his hands and wrists, for example, had a loveliness abandoned by most men of his and the rising generation. Among his most significant gifts was his masterly partnering; he helped a ballerina’s individual temperament bloom because she was secure in his arms.

For his final appearance, Neal danced the first-arriving of the two male leads in Balanchine’s poignant Serenade, the ballet for which the twentieth-century’s greatest choreographer thought he might, just might, be remembered, and the male lead in Balanchine’s Chaconne,

Neal’s dancing in Serenade, with Jenifer Ringer, was all tenderness, gravity, and regret. His deference to the presence and plight of the figure Ringer represented seemed to echo Balanchine’s much-quoted declaration “Ballet is woman,” the implication being that man (if the choreographer) is her servant or (if the dancing partner) her cavalier. Neal wasn’t quite all-subservience, though. Dancing alone, for instance, he’d execute a high, wide leap, imprinting the image of his perfectly aligned body on the air so indelibly that he seemed, for a few seconds, fixed in space, while the air surged around him.

In Chaconne (to plangent music taken from Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice), Neal and Wendy Whelan were equals as they danced first among the Blessed Spirits (an ever-shifting matrix of young women with flowing skirts and unbound hair), and then became the monarchs of a kingdom full of delightful if inscrutable protocols that only a scholar of early classical music or a child steeped in fairy tales could explain. As did the originators of their roles, Suzanne Farrell and Peter Martins, Whelan and Neal made the whole business cohere.

Toward the end of the ballet, Whelan, who seemed to be dancing with great joy, streamed all her focus in two marvelous solos toward Neal instead of to the public, expressing–spontaneously, I think–her affection for her longtime colleague.

It Was Roses, Roses, All the Way: Philip Neal and friends

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Then came the curtain calls: the Chaconne cast applauding the retiring star; Neal responding to Whelan with a real kiss; long, swirling silver streamers shot out of nowhere toward the hero of the hour. Next, the parade of former and current colleagues, bearing flowers. Among them were Kyra Nichols, now retired, Neal’s most important partner in the course of his career; Albert Evans, due to give his own farewell performance one week hence (snappily dressed for the occasion, Evans kissed a single red rose before offering it to his buddy); and Darci Kistler (the last ballerina selected by Balanchine), whose farewell will come the following week and close the season.

Peter Martins joined the gang of Neal fans, as did many other members of the company. The “pedestrian” in the congratulatory crowd was Neal’s partner, that gentleman’s walk-on appearance being only suitable since, in recent years, ballerinas have been bringing their husbands and children onstage for similar celebrations. Little nosegays were flung stageward by admirers in the audience, and finally Neal stood alone on the carpet of petals, his posture recognizable from curtain-call photos of the foremost male dancers down the decades. Standing erect yet subtly sculpted, like a classical Greek statue, he held one hand over his heart–as if he meant it.

This last goodbye was touching–many in the audience wept–because it made clear as never before how important Neal’s dancing has been to the company’s profile. America doesn’t hold with aristocracy and Neal’s dancing is unmistakably American–plainspoken and without airs–but he is nevertheless a prince.

Farewells stir up memories. I first encountered Albert Evans offstage when New York City Ballet had recently promoted him, Philip Neal, and Nilas Martins to soloist rank and I was interviewing them as a group. When all the obvious points had been covered, the conversation turned casual and Evans mentioned, modesty barely veiling his pride, that he had just moved into a new apartment. “What style are you decorating it in?” I asked. I should have known there could be only one answer, and he came right back with it: “Albert Evans style.”

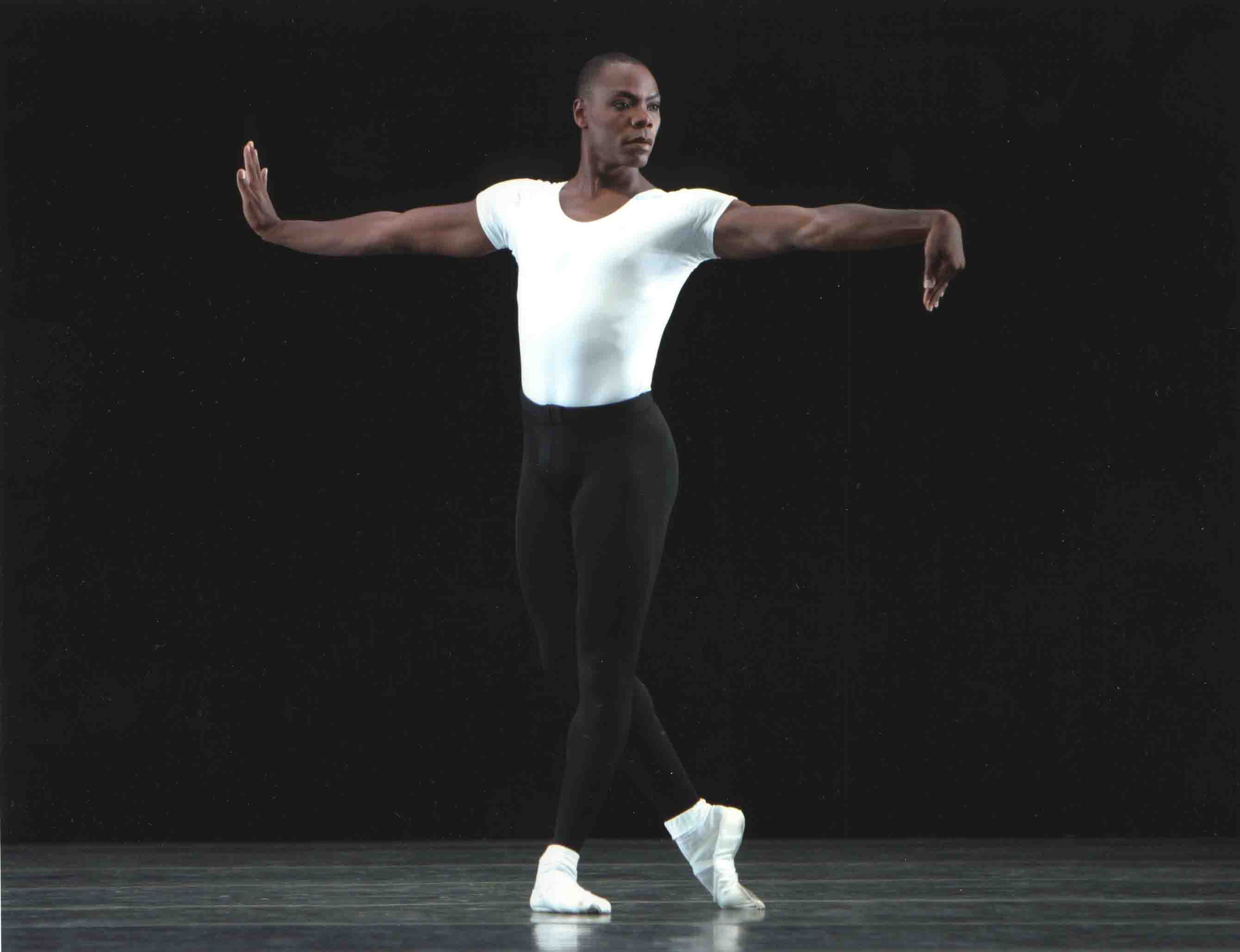

Phlegmatic: NYCB’s Albert Evans in Balanchine’s Four Temperaments

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Time passed. He danced. Evans was a beautiful classical dancer with an on-the-mark yet velvety technique. On appropriate occasions he countered its sheer beauty with streetwise alertness to possible danger–around him or within him. This profile, obviously welcome in contemporary choreography, gave an added dimension to Balanchine’s work, especially the abstract “leotard ballets” that lie at the heart of the City Ballet repertory. In lighter works he gave his sunny personality free rein.

In 1995 the company elevated Evans to the top rank of principal dancer. He continued to dance. When a slew of new ballets was needed for one of City Ballet’s periodic festivals, visiting choreographers vied to use him. He was an extraordinarily charismatic presence, and a showman par excellence. From the moment of his entrance he could persuade the audience that something compelling was going on.

Eventually, as happens to us all, but later, the body began to exact its compromises. On June 20, Evans danced his last performance with City Ballet, appearing in a rakish duet from William Forsythe’s Herman Schmerman; Balanchine’s Four Temperaments, a touchstone of neo-classicism; and a flower-filled, confetti-studded series of curtain calls in which he received an enthusiastic homage from his colleagues, who crowded onto the stage, and from the standing, robustly clapping, vociferously appreciative audience calling out his name.

Smilin’ Through: Albert Evans and friends

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The two indelible moments in those multiple curtain calls were Evans’s half-reclining on the floor behind the pile-up of bouquets as if he were a jokester mocking his own death and burial, assuring the spectators it was just a prank, and his standing and shedding his soft white ballet slippers (part of the danseur noble’s uniform) and throwing them–as if to say “That’s that!”–into the lush, soft-petalled mound.

Perhaps relinquishing performance at the highest level when you still have half your life to live has to be handled ironically to be endured. But, even if unintentionally, Evans had delivered another–ingenuously hopeful–message at the close of The Four Temperaments. As the parallel lines of the entire cast formed a runway for flight toward some unidentified but implicitly cosmic destination, Evans turned his head sharply away from the audience and into the wings as if he’d suddenly discovered something riveting in the distance and was moving straight toward it.

American Ballet Theatre’s Sleeping Beauty is a scandalously inept version of the Petipa classic. Changes have been made to the company’s current production since its premiere in 2007 in the hope of correcting this or that absurdity–choreographic, narrative, or decorative–to no avail. It’s wrongheaded from the word go and a desecration of the Tchaikovsky score, of which it omits huge chunks because today’s audience is assumed to have no sitzfleish.

Let’s say, to be generous, that the people responsible for the production–Kevin McKenzie, Gelsey Kirkland, and Michael Chernov–fully appreciated the beauty of the traditional version of the ballet, understood its deep metaphoric significance (instead of confusing a fairy tale with realism), and had listened to what the music was clearly telling them at every turn. If so, they were simply unable to bring their knowledge to making a fresh version that a perceptive dance viewer could admire. I’ve stayed away from this Beauty since I reviewed its premiere and returned only to see the Royal Ballet’s Alina Cojocaru and the Bolshoi Ballet’s Natalia Osipova dance Aurora–matinee and evening respectively on June 19, at the Metropolitan Opera House.

Both ballerinas are small, slight women and, for a dancer, anatomy is in part destiny. If the petite dancer bubbles with energy, she’s a natural for soubrette roles; one with more lyrical leanings seems born to arouse pathos.

Fish Dive: Alina Cojocaru and Jose Manuel Carreño in ABT’s Sleeping Beauty

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Cojocaru certainly looks as fragile as a porcelain figurine, but I can’t understand why she chose to portray Aurora largely in the pathetic mode. To be sure, there’s a curse looming over this heroine, yet it doesn’t seem to undermine the radiant ebullience the world’s most unforgettable ballerinas have given her at her Sweet Sixteen party. (Aurora may not even know about the dark prophecy since, seeing a spindle for the first time, she finds it a fascinating toy.) And I suppose, when the Lilac Fairy reveals her to the Prince as an impalpable vision, there’s some melancholy to be found in the notion (ignored in all the other interpretations I’ve seen) of Aurora’s yearning for a love that seems infinitely delayed. But at her coming of age celebration (until the malicious Carabosse intrudes) and at her wedding, Aurora is triumphant, a young woman truly coming into her kingdom.

I imagine the quality Cojocaru is aiming for is reticence–an understated interpretation that would register as refined, elegant, and, in the end, touching. What I saw in her single ABT performance, however, looked dry and constricted–more repressed than refined, more thought through than danced through. No surprise, then, that this Aurora failed to delight.

This is not to say that Cojocaru’s rendition wasn’t technically superb. On the whole it was. And not just in the obvious places–the preternaturally sustained balances of the Rose Adagio and (thanks to Jose Manuel Carreño, a prince worth waiting for) perfection in the series of fish dives that climax the grand pas de deux of the Wedding Scene. Less obvious moments were equally gratifying. Take, for example, Aurora’s traveling down a diagonal line of her kneeling suitors, pausing briefly before each one in arabesque, then descending seamlessly from full point to flat as, with a Japanese sense of propriety, she delicately shades her face from the men’s view.

In the course of the past six years or so, I adored the dancing I’d seen from Cojocaru here in New York, with only slight and occasional reservations about a lack of full-blooded passion. In the Beauty performance I just saw–the ballerina’s single appearance with ABT this season–I felt the balance had tipped in a discouraging direction. Cojocaru can’t go back to what she once was–no artist can–but there’s always the possibility of a heartfelt exploration of what one might be next.

The diminutive Osipova is the ballet world’s young favorite and, at the moment, the general public’s too, having emerged relatively unscathed after being mugged in the Lincoln Center nabe. Her performance of Aurora on the 19th was her very first in The Sleeping Beauty–anywhere.

Wedding Redux: Natalia Osipova and David Hallberg in ABT’s Beauty

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

If the event wasn’t an unqualified success, it’s because she isn’t the Aurora “type.” Lacking both innate charm and radiance, she’s not convincingly girlish in the birthday scene or able to project a womanly glow for the wedding scene. (Yes, these are old-fashioned qualities but Beauty is an old-fashioned ballet–and a keeper nonetheless.) There were many hints in Osipova’s performance that she knows what the story and music require, but she can’t produce these effects yet; they’re still just ideas and they don’t mesh with the personality her dancing regularly reveals. She’s a hoyden–spunky and fearless, a cousin of Tom Sawyer and the heroine of Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo, who wants to ride with the cowboys.

The gods know she applied all her stunning technical skills to the task. Leaping is Osipova’s preeminent gift. She seems to rise up from nowhere and, as Nijinsky described his own uncanny elevation, “just pause in the air for a little before you return” or let herself be blown by an unchartable wind to another lofty niche in space. Just as her preparation for these amazing flights is invisible, her landings may be invisible too. At any rate, I’ve never noticed them.

She’s a world-class turner too. I especially liked her supported pirouettes with the four princes come from afar to woo Aurora. With the first suitor she does a single pirouette; with the second, two, and so on. I’ve seen many a ballerina avoid this challenge, since it’s tricky to keep the triple and quadruple pirouettes clear. Osipova, I suspect, could bring off the feat in her sleep.

And of course there are her sky-high extensions, breathtaking for those who like this sort of thing. I don’t; they make the working leg look detached from the body, as is the case with even the most “realistic” jointed doll.

It’s tempting to weigh Cojocaru’s Aurora against Osipova’s because of the circumstances under which one had to view them, both ballerinas appearing one time only in the role and on the same day. Thus you could find yourself saying, “Well, Osipova’s balances were secure, but Cojocaru’s outshone them” or “Cojocaru seemed willfully to have decided to damp down her interpretation, but Osipova may already be invested in the drama of Aurora’s growth to maturity.” Such remarks might be true but they’re not very pertinent, dance being an art, not a competition, no matter what TV shows and those gold and silver medals propose. Besides, both Cojocaru and Osipova were outclassed by a model who is now hors concours: Margot Fonteyn.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Tobi, your description of these retirements is full of respect and beauty.

I was especially moved by your description of Albert Evans’s exit in “The Four Temperaments” and the smallest shift in head gesture that sends so great a message–not that the message is a telegram in any way specific (no mothers-in-law for Evans!), but that the smallest shift can rock our world. It takes someone who has seen the works and the dancers often enough to capture those small shifts and I thank you for it.

Seeing Things is an excellent full meal.

Before the Neal farewell performance started, Kyra Nichols, accompanied by her husband and elder son, said to someone who commented on her showing up, that she would not miss this performance because it was Philip.

Alina Cojocaru did a wonderful Aurora (in the Mariinsky reconstruction) in St. Petersburg some years back. I have beautiful photos of the whole performance. She was partnered by Andrian Fadeev, another great danseur noble, in my opinion.

I enjoy your “eye” and your writing very much.

Tobi, it was great to see you at Philip Neal’s farewell. I enjoy your writing so much.

I didn’t see Cojocaru’s “Beauty” but loved Osipova’s. I wonder if Kolpakova coached them both. Those who have never seen Fonteyn have little basis for comparison. One of the few good things about aging is that you do.

Your comments are so perceptive, you should be back writing for a major outlet.

What you wrote about Philip Neal is something I love about men, and it is so rarely seen.

Tobi, your critique of Alina Cojocaru’s performance makes me question your sanity. You focus on the trivial and unimportant, and ignore the big picture. Her performance was breathtaking. Three thousand eight hundred ballet-goers can’t all be wrong, as you very well know from the decibel volume of the cheers she received.

You know I am a fan of your dance writing, but this time you’re totally off the deep end.

Regards,

Stephen

Tobi, brava, brava, and brava again for the concluding paragraph of this “diary” entry, slamming dance as competition rather than art. I would add that artists of every stripe are constantly in competition if they’re any good, not with other artists, but with themselves.

I also enjoyed the descriptions of the retirement parties, as it were, for Albert Evans and Philip Neal and am wondering if you or any of the commenters have seen the Interpreter’s Archive recording of Todd Bolender coaching Evans in the Phlegmatic” section of “The Four Temperaments,” just the first minute or so of the first entrance. It’s fascinating. (The Bolender footage can be accessed at the Dance Division of the New York Public Library at Lincoln Center and, I believe, at several academic libraries around the country.)

LOVED it ! thank you

I am moved by your descriptions of Philip Neal’s and Albert Evans’s farewell performances. As I read, tears welled in my eyes, too. This surprised me, but all of us who are affected by deeply felt movement will sorely miss those dancers who embody it. The qualities that these dancers bring to choreography tug at the heartstrings.

Thank you, Tobi, for your peerless reviews.