Ballet Diary No. 6: American Ballet Theatre: All-Ashton Program; All-American program (ABT’s season runs through July 10 at the Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center, NYC; New York City Ballet: Mauro Bigonzetti’s Luce Nascosta, (NYCB’s season runs through June 27 at the David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC)

Note: This is No. 6 in the series “Ballet Diary”–comments on the 2010 spring seasons of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, along with related performances. To read previous pieces in the series, click here: No. 1; No. 2; No. 3; No. 4; No. 5. The completed “Ballet Diary” series will comprise nine essays.

After giving the general public what marketing believes it craves–three weeks straight of program-length works–American Ballet Theatre gave hard-core (or is it old-fashioned?) dance aficionados a break with a week of mixed-repertory programs. Mind you, the mix was always governed by a specific theme, assuring the ticket buyer, by means of a label, that he or she was making a solid investment. I went to see the All-Ashton and the All-American programs.

Birthday Party: The full cast of Frederick Ashton’s Birthday Offering

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Only half of the Ashton program offered a goodly amount of sheer pleasure; the rest was a demonstration of ABT’s efforts to dance in a style foreign to it. Frederick Ashton’s ballets are quintessentially English: On the surface many of them have a fairyland lightness–the exquisite grace of a highly mobile torso set against delicate, precise footwork; at the core lie feelings that pierce the heart.

ABT’s rendition of Ashton’s 1956 Birthday Offering made me think of the Advanced Placement exams taken by college-bound high-school students: an occasion to test their chops in a subject about which they’ve learned a great deal, but hardly everything they need to know for genuine mastery.

Created for the 25th anniversary of the company that had just received its charter as the Royal Ballet and set to deliquescent Glazunov music, the piece is danced by seven couples (one more equal than the others). The full cast opens the ballet with a promenade of the pairs, which then evolves into a group dance that still recalls the idea of a promenade. Ashton knows his trade and provides the obligatory elements of a formally constructed display piece–a duet for the chief couple and an ensemble dance for the men. But the astonishing core of this ballet is seven solos for the women, one after another, each ingenious and difficult in an a unique way. The difficulty is meant to be invisible–masked by the dancers’ prowess. For this you need seven women of the highest technical caliber and individual distinction. I’d venture to say that ABT doesn’t yet have the personnel equal to the task.

Still, the attempt was glorious. Usually, in the performing arts, nothing counts but first-class results, but here you could see gifted, proficient, and experienced dancers learning and trying, learning and trying. Their understanding of how Ashton’s choreography should be danced, along with their persistence and humility, cheered me immensely. Those solos–an echo of Petipa’s individual dances for the fairies at Aurora’s christening–are still at the point where they’re being executed step by step, a concern with correctness foremost. Rarely does the material expand into dancing that flows naturally, as if it were almost spontaneous. Could this facility come with time? Could ABT borrow a significant number of rehearsal hours from the production of new works that are no more than gimmicks and tomfoolery and, instead, spend them on the treasures of earlier decades–the Ashton repertory, the Tudor repertory, even the Balanchine repertory (with people to coach it merely a stone’s throw away)? Classical choreographers of genius being almost non-existent nowadays, might this not be a perfect time to look to–and preserve–the glories of the past?

The Awakening pas de deux from Ashton’s version of The Sleeping Beauty was basically a disaster area, apart from Paloma Herrera’s making a timid but credible attempt at acting instead of merely dancing Aurora with her familiar technical panache. In Perrault’s version of the fairy tale, the young woman says, immediately after her kiss-alarm clock rings, “Is it you, dear prince? You have been long in coming!” I hated to think of this 116-year-old (but nonetheless radiant) princess’s having spent the previous century in the milkmaid-style nightie Herrera wore. The object of her instant affections (although Perrault slyly hints she may have glimpsed him in her dreams) appeared to be sporting the uniform of his soccer team. Played by Cory Stearns, he was not worth waiting for; Stearns lacks both the technique for Ashton’s subtle but challenging choreography and the necessary dramatic presence.

Diana Vishneva’s partner for the Thais Pas de Deux, Jared Matthews, was something of a cipher too, but Vishneva was utterly compelling as the veiled woman who comes to her worshipper as if in a high-minded–almost spiritual–version of an erotic dream. Deliberate and sinuous in her movements to Massenet’s music, blank in her expression but fiercely concentrated, the Russian ballerina slowly drew in the audience with the kind of magnetic force there’s no point in resisting. Through her portrayal Ashton preached his gospel, once again: Woman’s power lies not simply in beauty, but in beauty that’s coupled with mystery.

Faerie Grace: ABT’s Gillian Murphy and David Hallberg in Ashton’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Created in 1964, to Mendelssohn’s delectable music, The Dream is one of Ashton’s greatest triumphs and ABT did it justice, evoking Shakespeare’s antic and romantic fairyland, forever entwined with the predicaments of mere mortals. The company’s female ensemble succeeded in producing the effect of quivering butterfly wings, while the principals outdid themselves, dancing Ashton’s choreography with both freedom and credible style, at the same time conveying the temperament of their characters.

Gillian Murphy, as Titania, was splendidly imperious and willful; David Hallberg’s Oberon, quick to match her and quick to anger. Hallberg went all out in his dramatic interpretation, with passages of sublime authority (aided by his flawless technique, which combines lyricism with virtuosity)–and little moments in which he indulged in the refined fussiness typical of a dealer in high-end antiques. I can’t imagine ever forgetting his Oberon’s sudden flares of temper, his self-confident haughtiness, or his delivery of the long skeins of assorted turns that Ashton originally set for Anthony Dowell.

Murphy made much of the lust Titania has for Bottom, the workman temporarily transformed into an ass, pressing the long donkey ears to her breasts and deeply embarrassed when Oberon confronts her with her transgression. These passages provide an important contrast with the duet–surely one of the jewels of twentieth-century choreography–at the end of the ballet in which Titania and Oberon find their way to a perfect union. As exasperated feminists will assert, she succumbs to him, but Ashton makes it clear that she does so of her own will.

Ain’t Misbehavin’: ABT’s Herman Cornejo as Puck in Ashton’s Dream

Photo: Gene Schiavone

The twisting, high-flying motions of Puck is just another feather in Herman Cornejo’s cap. This extraordinary dancer left his personal mark on the role by giving it a grotesque and servile tinge that was almost scary yet just right.

Julio Bragado-Young, as the transmuted Bottom, earns special mention for his point work. Without forsaking his masculinity, he delivered the unwavering line through the legs and the neatness of foot (hoof, if you will) that might be the envy of the girls in the advanced class of the company’s school.

Encountered first in a flyer for ABT’s season, the umbrella title “All American” for a ballet program seemed contrived to me. What difference could it possibly make that all three choreographers happened to be natives? All the difference in the world, as the performance proved. The trio of ballets–Twyla Tharp’s Brahms-Hayden Variations, Jerome Robbins’s Fancy Free, and Paul Taylor’s Company B share the lustiness of purpose, the theatrical ingenuity, and the bravado needed to pioneer uncharted ground that are typical of American ventures. It helped, of course, that all three ballets are keepers.

For The Brahms-Hayden Variations, choreographed for ABT a decade ago, before Tharp became dangerously distracted by Broadway, 30 dancers assemble to create ever-shifting matrixes, the beautiful logic of which you sense, profoundly, even if you can’t grasp–or even see–all of the marvels on a first viewing. Admittedly, this ballet is too dense–it’s like advanced math, visualized–yet any little passage, or even phrase, that you do seize seems perfect for its moment in time and position in space. The piece has a crackerjack organization that’s gravely formal even when what’s going on step-wise seems decidedly peculiar.

As is her custom when operating in the classical-dance world, Tharp roots her choreography in the academic ballet vocabulary, but that’s just a base. She takes every traditional move to the extremes she envisions for it, infiltrating the material along the way with borrowings from jazz, modern dance, gymnastics, pedestrian moves–you name it. Watching this dance, you feel blasted by possibility.

ABT’s dancers stepped up to the challenges, eager and able. Despite a couple of tricky moments, they gave the piece the high-caliber performance it demands and deserves.

What’s American about Brahms-Haydn? Tharp’s self-invention and stubborn drive to push beyond what we already know; the polyglot nature of her dance language; her belief that complexity needn’t be abstruse but, actually, fun.

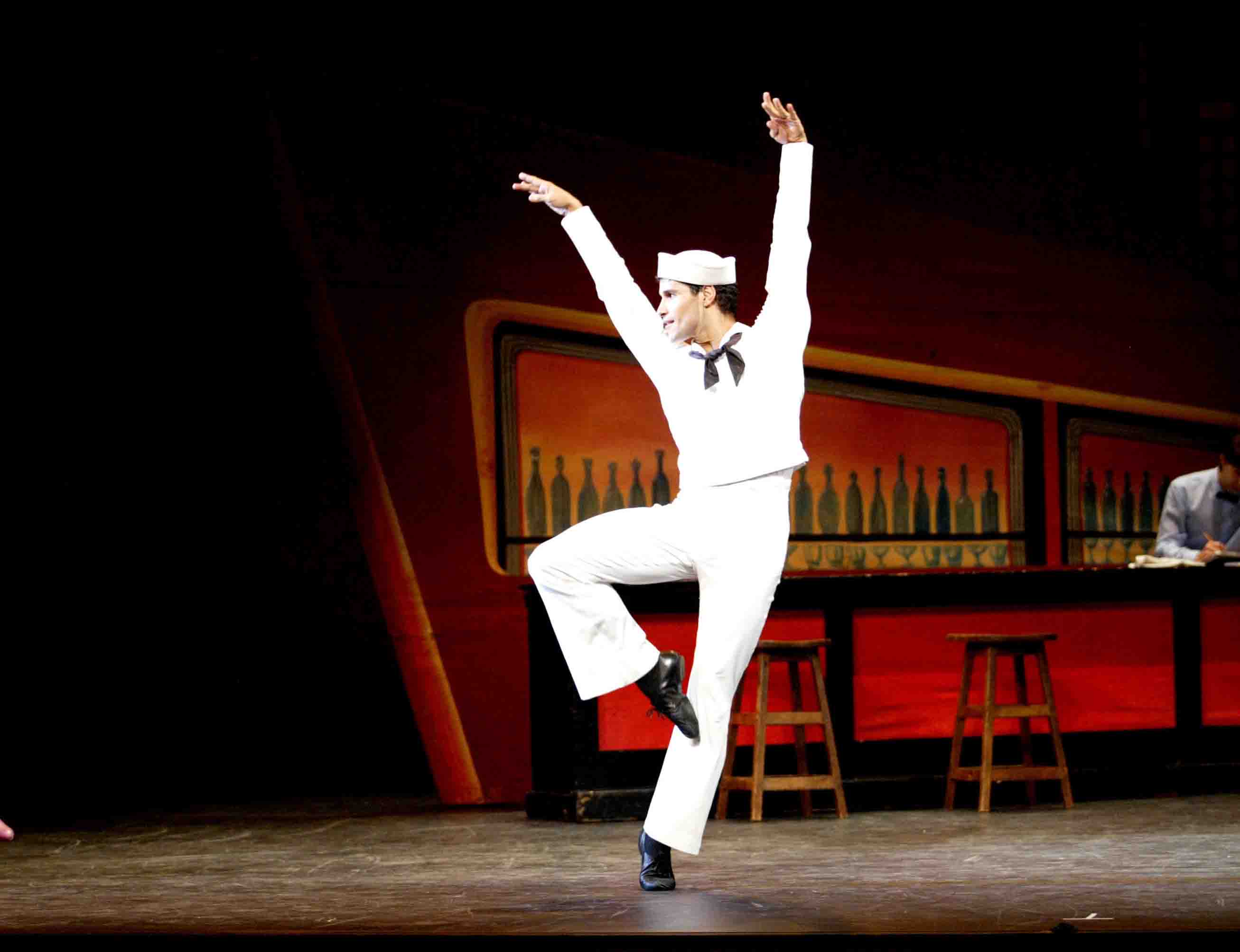

Ocean’s Motion: ABT’s Jose Carreño in Jerome Robbins’s Fancy Free

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

An instant hit in 1944, Fancy Free, a collaboration between Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein, is one of the rare ballets that tells a story but needs no libretto. It’s perfectly clear and perfectly wonderful. Three sailors–fast friends–on shore leave in the big city, on the lookout for dates. One, then two gorgeous prospects stroll by. After a sassy encounter, then a tender duo the question remains: How to divvy up these terrific femmes? All five repair to the corner bar (the brilliant set showing both sidewalk exterior and watering-hole interior is by Oliver Smith) where each guy struts his stuff in a solo revealing his temperament: poetic; athletic; sexy. The competition being inconclusive, the guys naturally resort to fisticuffs. The girls depart in a huff. Bereft, the sailors reconcile under the street lamp, ruefully accepting their failure with the fair sex, until . . . Just before the curtain falls, gorgeous prospect number three strolls by, and they go chasing after her, full-speed.

Having watched Robbins teach Fancy to New York City Ballet dancers–the sessions included consulting a film of the original cast–I can guess that the choreographer’s well-known obsession with accuracy down to the last detail has played a major part in the ballet’s surviving its transmission to several generations of dancers pretty much intact. The ABT cast I saw this season produced not only the steps and gestures but also–equally important–the personalities of the characters, even to the incredibly beautiful blonde walk-on, who may provide the shortest description ever made of the term narcissist.

Best of cast prize goes to Jose Manuel Carreño, who does the solo originally danced by Robbins himself. It was inspired, Robbins has said, by the sight of a sailor dancing in a bar, his arms wrapped around a chair in lieu of a flesh-and-blood partner. In the choreography, the chair is gone and the arms embrace empty space (enticing the imagination), but the rhumba’s swiveling hips are definitely there. Carreño adds his own seductive personality.

What’s American about Fancy? It gives us the U.S. of A. in a nutshell–a land of good-natured dreams about youth, buddies, easy pick-ups with no dire consequences (indeed, no consequences at all), and living contentedly in the moment (even if there’s a war going on). Some of those dreams have corroded in the last sixty-six years, yet the ballet remains effective and beloved.

Like Fancy, Paul Taylor’s Company B, created in 1991, refers to World War II. It’s danced to recordings of the Andrews Sisters’ irresistible pop songs and, though its men are in mufti, often dancing ebulliently with sweetie pies in bobby-sox, from time to time they march in silhouette behind an upstage scrim, shooting and falling. Towards the end of the ballet, the war impinges directly on the world of upbeat spirits: The irrepressible antics of the bugle boy are quenched with a single bullet and a woman mourns the death of her soldier husband, acknowledging that while life will go on for her, he will never be replaced in her heart.

ABT gave the work a cast largely composed of artists who can play down-to-earth people; no one on stage seemed to be longing for roles as impalpable spirits, abstract choreography, or point shoes.

What’s American about Company B? As with Fancy, the picture of a memorable era in our country’s history–this time created in retrospect and letting the dark veil the light. The jitterbug moves, all the rage in the Forties, that Taylor embeds into his modern-dance choreography. The absence of swans.

Cater-corner from the Metropolitan Opera House, at the David H. Koch Theater, New York City Ballet presented the premiere of Mauro Bigonzetti’s Luce Nascosta (Unseen Light) on June 10. The sixth of seven new works the company has commissioned for its “Architecture of Dance” festival, the ballet has music commissioned from Bruno Moretti, a frequent Bigonzetti collaborator, and an overhead–in the middle, mercifully a good bit elevated–sculptural installation by Santiago Calatrava, who has been the festival’s architect in residence, so to speak, available for the new works.

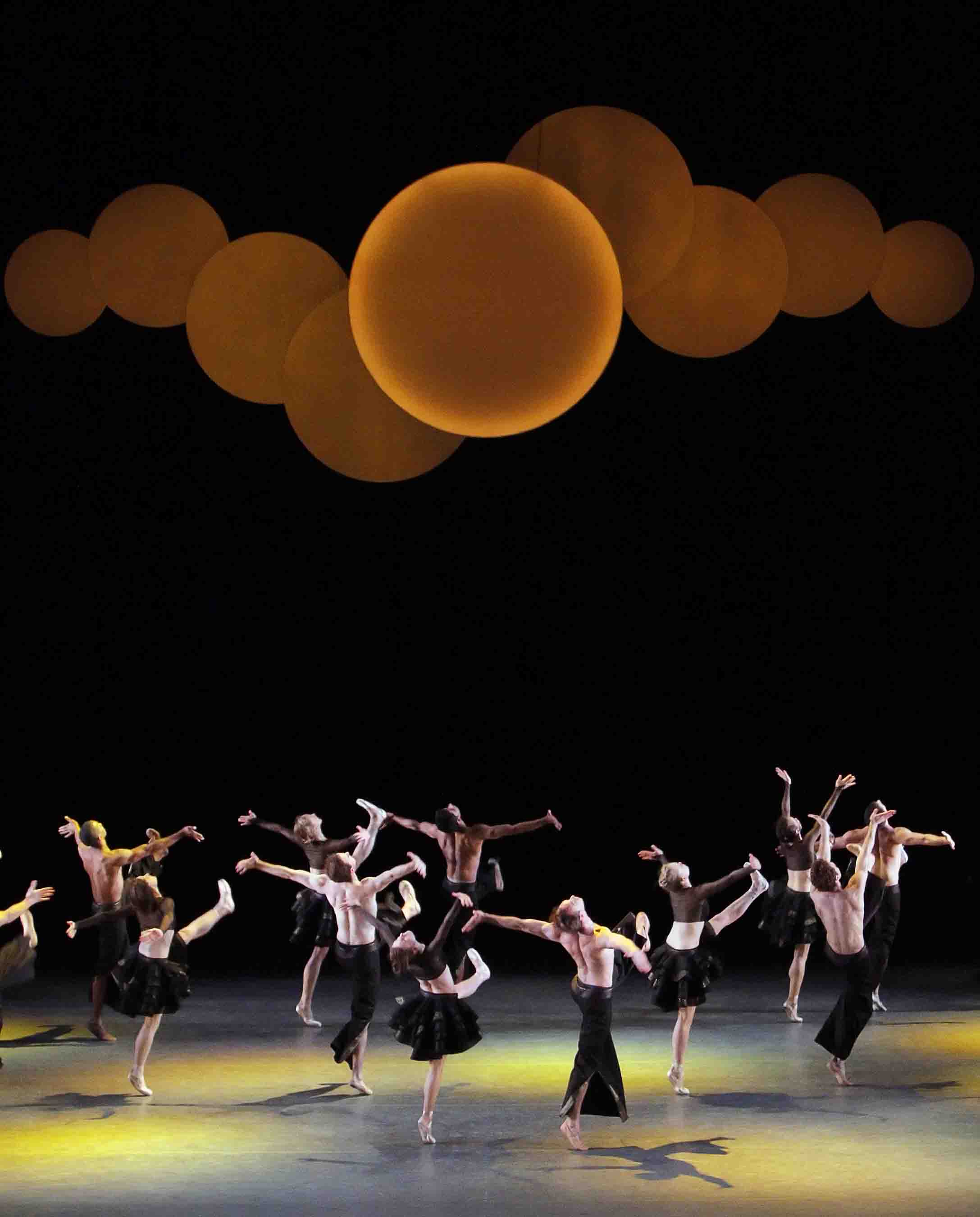

Darkness at Noon: NYCB dancing Mauro Bigonzetti’s Luce Nascosta. Installation by Santiago Calatrava

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The piece opens with figures barely visible on the darkened stage. Above them hangs Calatrava’s contribution, a glowing, bronzed sun that, in the course of the dance, will extrude several baby suns to either side, then gather them back, hinting at some metaphoric significance that’s never defined. As the space grows marginally less dim, a couple dances what looks like a jagged version of an apache duet, the steps and rhythms skewed, as if taunting classical-dance harmony.

Actually the dancers’ costumes are the first thing that strikes you. The men are bare-chested, with supple black trousers given a boot cut gone wild, splitting the garment’s seams from the calf down. The women are bare-midriffed. You might suspect that the fabric thus “saved” is then re-purposed to give them their long, skin-tight sleeves. Most prominent are the ladies’ short, black, extravagantly ruffled skirts, which suggest the plumage of an exotic bird. (Later, when the spectacularly long-legged Teresa Reichlen performs her solo of distortions, using her glutes to thrust her skirt out behind her, she resembles an ostrich. A charming ostrich, you understand.)

Clothes Encounters: Adrian Danchig-Waring and Teresa Reichlen in Luce Nascosta

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Anyway, by the time you’ve taken in the initial maneuvers and sized up the costumes, the full cast forms a double horizontal line, women foremost, the men stalking them. They look like a Spanish-style chorus line preparing for stardom in Vegas. Singled out next is a woman (Ashley Bouder) whose face is nearly hidden by a stylish loose bob. She seems to be the comedian of this errant troupe–though you must understand that nothing about Luce Nascosta is in the least funny–so after a peculiar solo she gets to do a grotesque pas de deux. Now and then, the men execute bits of gesture from Indian dance–maybe to indicate the power of ritual, maybe in homage to Maurice Béjart.

Well, you don’t need to hear much more about the goings on. They remain simultaneously pretentious and tawdry–until Moretti’s score changes its disjunctive tune (duly larded with festive scraps of “world music”) and grows sentimental and sappy, as if for the happy ending of a pre-Sixties romantic movie. The population duly takes its cue and manages to move, halfway anyway, to a less fraught life style. For me, the endless reconciliation passage, with the women skidding on point into their partners’ arms, was the last straw.

To distract myself from my dismay at the cheap aesthetic (if that’s the word) of Luce Nascosta, I tried to grasp what the ballet is “about.” I concluded, half-heartedly, that it deals with the sexual mores of foreign climes that are too weird for us–not being Margaret Meads–to understand, but not too weird to titillate us. Then I realized that I have never once wondered what Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco is about.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Too much great stuff to absorb in one reading.

One has to come back again and savor phrases

and thoughts, little by little.

Thanks, Tobi, marvelous, as always, but especially wonderful today. It made me long to see Ashton’s “Dream” again. I saw it decades ago in London, but haven’t much hope of seeing it any time in the future.

Our serendipitous re-meeting, near the red, green, yellow, purple, orange of fruits and vegetables at Fairway—college-mates who hadn’t seen each other for centuries—has felicitously broken the general distance I’ve kept from dance all these many years. It began with my departure, amidst adolescent crisis, from stardom at the High School of Performing Arts (class of ’54). Invitations to Fall for Dance and BAM and the Joyce in recent years have established a re-connection. I fully enjoyed absorbing the perspicacious dynamics of your review. An entertaining and enlightening dance of words in itself!