Ballet Diary No. 4: New York City Ballet: Christopher Wheeldon’s Estancia (NYCB’s season runs through June 27 at the David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center); American Ballet Theatre: John Neumeier’s Lady of the Camellias; Don Quixote; Alicia Alonso’s 90th Birthday Celebration (ABT’s season runs through July 10 at the Metropolitan Opera House, Lincoln Center)

Note: This is No. 4 in the series “Ballet Diary”–comments on the 2010 spring seasons of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, along with related performances. To read previous pieces in the series, click here: No. 1; No. 2; No. 3. The completed “Ballet Diary” series will comprise nine essays.

If you want to revel in evocations-of-the-untamed-land, go to Willa Cather’s My Ántonia or raid the kids’ bookcase for Laura Ingalls Wilder’s “Little House” series. Do not, for love of Terpsichore, consult Christopher Wheeldon’s latest effort, Estancia, for New York City Ballet’s “Architecture of Dance” season.

Horseplay: Christopher Wheeldon’s Estancia for NYCB

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The piece, which had its premiere May 29 at the David H. Koch Theater, is named for a score commissioned from the Argentinean composer Alberto Ginastera by Lincoln Kirstein for Ballet Caravan, one of the forerunners of City Ballet. George Balanchine was to have provided the choreography but the little company folded before he set to work and the music, composed in 1941, wasn’t given a dance realization in the States until Wheeldon came along.

The title of Ginastera’s score, which Wheeldon co-opted for his ballet, means ranch. And that’s where Wheeldon takes us–to Argentina’s Pampas, a landscape that features dizzyingly wide horizons to which one gazes across enormous stretches of untrammeled space and mettlesome people who live close to the earth. Wheeldon’s treatment lends the gauchos (something like America’s cowboys) a pack of wild horses instead of more prosaic individual mounts. It can’t fail to remind audiences of Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo, which conjures up our western plains, their settlers’ bond to its wide horizons, and, for the men, a life on horseback.

Estancia tells a story derived from Ginastera’s own synopsis and a poem–about the beauty of the simple life–that inspired him. A city boy (Tyler Angle) yearns to become part of the rural workers’ domain, identifies a potential sweetheart (Tiler Peck) there, is rebuffed by her, then accepted when he tames one of the natives’ wild horses. Midway through this unlikely scenario, a group of city folk, thinking themselves superior because they’re urban, insult the locals as they try to lure the young man back to town. The two sectors reconcile so the ballet can end with a lusty dance of celebration.

Here’s where Wheeldon goes wrong:

(1) Everyone in Estancia–human and equine alike–moves like a highly trained ballet dancer, the women on point. Even the formal stage patterning recalls conventional classical ballet. This doesn’t help the viewer imagine the down-to-earth beauty of life in the Pampas.

(2) The Horses: Humans as horses are tricky. Ballet dancing humans as horses–lavish manes and tails whipping about a vertical body–are ludicrous. Four mares (on point) in a bit of pas de deux-ing with a quartet of gauchos are beyond the pale. Wasn’t their lone stallion (Andrew Veyette, undeterred by absurdity) enough for them? As for The Boy’s getting reins on the most slightly built mare and thus winning The Girl, the taming is a non-event, both physically and dramatically. Maybe Wheeldon should have had The Boy tackle the stallion to create a more striking, evenly matched contest.

Sweethearts: Tyler Angle and Tiler Peck in Estancia

Photo: Paul Kolnik

(3) The Girl of His Dreams: She starts out as feisty as they come, a role model you’d want for your goddaughter. But the moment she begins to reconsider The Boy as a romantic partner, she starts to melt into sweet, soft sentimentality. The couple’s love duet, which ends with their cuddling on the floor, is so generic and sappy as to be embarrassing.

(4) The Singer: A distinguished baritone (Philip Cutlip) performing in operatic style–in the Pampas?

(5A) Class Conflict: Wheeldon’s depiction of the snobbish city folks is simply too crude: ladies of the Forties dressed for visiting outlying districts–hats, gloves–being disgusted by horse droppings, and so on.

(5B) Class Rapprochement: Every musical-style show needs an upbeat finale, so rural and city folks unite for a generic display of joy, waving red bandannas. If Wheeldon is being ironic here, lovingly parodying old-time Broadway musicals (as, say, Alexei Ratmansky might), he’s changing his tune too late in the game.

I don’t blame the dancers. Even if the ensemble occasionally seemed half-hearted, the leads, Peck and Angle, gave the material their all and Veyette retained his self-contained visceral power (to say nothing of his dignity) in his peculiar assignment. Nevertheless, Estancia ranks high among the dopiest ballets I’ve ever seen.

The décor for Estancia–mainly a jazzy front cloth and a blurry backdrop giving a domesticated impression of the Pampas–is by Santiago Calatrava, whose scenic treatments are supposed to be the lynchpin of the City Ballet’s “Architecture of Dance” festival. He does far better work designing buildings. Carlos Campos created the costumes–from the outré equine disguises to outfits for the city folk that focus more on period detail than on theatrical impact. The Boy, for instance, initially wears a business suit and tie–complete with tie clip.

Ill-fated Love: Diana Vishneva and Marcelo Gomes in Neumeier’s Lady of the Camellias

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Need a reminder of the story? It takes place in Paris back in the mid-19th century, when a diagnosis of TB was a sure death sentence (and a favorite component of the era’s art). Marguerite, who maintains a heady lifestyle as a courtesan, is young, irresistibly attractive, and infected. Armand, who comes from a well-placed family that presents an unsullied façade to society, meets her, and, as the annals of high romance would have it, their fate is sealed. Their love grows from wild fling to passionate commitment. Armand’s straight-arrow dad begs Marguerite to let his son go. She complies, deserts her lover without explaining that she is sacrificing her own happiness to his good reputation, and, lacking other resources, returns to her demimondaine trade. When she and the stricken Armand meet again, he humiliates her publicly. Time goes by, eventually bringing a poignant reconciliation, but of course it’s too late and Marguerite expires.

Obviously a good bit of this tale is impossible to realize through dancing. How, for example, is a spectator supposed to know the contents of portentously delivered letters and a diary? Neumeier refuses to admit that written text and human movement in space don’t employ identical means of expression. He has a slew of other problems as well.

He loves to tell a familiar tale from an unusual perspective. In Lady of the Camellias he manipulates the narrative’s time frame. The ballet opens at a postmortem auction of Marguerite’s possessions, with all the key elements of the story told in flashback and–or so the program note claims–from the various points of view of the three main characters. (Neumeier, like William Forsythe, makes himself understood more clearly through program notes than via what he sets on stage.)

What’s more, Neumeier can’t resist complicating matters. His ballet follows the suggestion of the Dumas novel and draws a parallel between Marguerite’s fate and that of Manon, told in the Abbé Prévost’s 18th-century novel of that name and later popularized through the eponymous opera by Massenet and the ballet by Kenneth MacMillan.

Of course if Neumeier didn’t make so much of the Manon story and if he cut out all his ballet’s padding–most of the ensemble work is mere window dressing–all he’d be left with is a one-act show. Perhaps this is as much as the core story needs, or so Frederick Ashton demonstrated.

Further complaints: Neumeier likes to combine the realities of everyday life with “artistic” fantasy. While he constantly juxtaposes the two modes, he never succeeds in getting them to blend naturally. The Manon business, for example, starts as a ballet within a ballet, which Marguerite attends, and extends into the realm of the hallucinatory when the figures actually invade her life. Neumeier gives this transformation stock treatment so banal that it’s unlikely to persuade the most credulous viewer to suspend his disbelief.

Courting Death: Vishneva and Gomes

Photo: Gene Schiavone

And then there’s the TB element, perfect for Neumeier, whose work so often dwells on the association of erotic desire and death. He takes his titillating morbid streak to macabre extremes here, with simulated sex punctuating the heroine’s wasting away and dying at tedious length.

As for the choreography per se, most of it is boiler plate, the ensemble work especially. But then there are those lifts. The ballet’s many intimate duets are rife with them. Up and around and upside down or twining like vines overdosed on Vigoro. They’re often awkward even when they come off as planned. When they don’t, quite, you fear for the dancers’ life and limbs. The worried spectator, noticing the near misses, is unlikely to understand the lift as ballet’s ultimate expression of ecstasy.

Of course the spectator has other matters to distract him. If, when listening to the score Neumeier has culled from Chopin’s piano works, both solo and accompanied, he recalls the choreography made to some of the same pieces by Robbins (in Dances at a Gathering) and Ashton (in A Month in the Country), he will have grave reservations about Neumeier’s skills. The fact that The Lady of the Camellias coarsely parodies Robbins’s choreography for the climactic “Grand Valse” of Dances at a Gathering hammers the final nail into Neumeier’s coffin.

Given the weaknesses of their material, the dancers worked hard for a credible interpretation of their roles and did their courageous best with passages that should earn them danger money.

It’s hard to know which is the more riveting–Diana Vishneva’s technical prowess (the articulate footwork, the fluidity, and so on) or her unflagging investment in a narrative ballet’s story and the life of the character she plays.

No, she’s not magical; she has no “perfume.” But she’s so very good at what she does that you’ve got to admire her–even, as her hordes of fans do, love her. As Armand’s stern father slowly and touchingly recognizes, Vishneva’s Marguerite is a courtesan with soul.

For reasons best known to himself, Neumeier has choreographed Armand as an awkward wimp. Mercifully, the fellow stops bumping into things early on as he explores the naughtier venues of yesteryear’s Parisian high life, but it takes a while before he stops throwing himself at Marguerite’s feet–literally as well as metaphorically. Marcelo Gomes–an imposing, solidly built, darkly handsome guy whose dancing is uniquely forceful and self-possessed–is not the man for this role.

Both artists were nevertheless superb at portraying the moments in which Marguerite’s flirtation and Armand’s infatuation turn into soul-stirring love, the kind that’s supposed to defy death or at least–in the fantasy realm of ballet, anyway–earn the couple an apotheosis.

Fatal Attraction: Roberto Bolle and Julie Kent

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Julie Kent and Roberto Bolle gave the leading roles a different cast and were more believable as a pair. Bolle’s lanky raw-youth looks made his seeming innocence and initial haplessness convincing (though I don’t know that the implied disparity of age between his Armand and Kent’s Marguerite was part of the original story). Given his height, harmonious proportions, and charming face, Bolle has inevitably been trained to play princes; you can see him aiming for purity in his every move. As for feeling, he seems to be striving to follow every bit of coaching he’s been given. He doesn’t act from his own heart yet, but his efforts alone are disarming.

Kent has spent the latter part of her long career expanding her ability to act. This has stood her in good stead in the last decade and does so again in her portrayal of Marguerite. At first she appears harder and more glittering than the vulnerable characters she plays so tenderly–so often and so well. From then on, she slowly reveals the progressive ravages of Marguerite’s illness, which go hand in hand with the deepening of her love until she seems to be a near corpse, kept alive only by passion. This effect is not simply something that can be taught or learned; it’s rooted in a charismatic quality one is born with. No matter how hard he tries, Armand can’t get Kent’s Marguerite out of his mind–and neither can her audience.

Apart from its exquisite vision scene, ABT’s version of Don Quixote–the venerable faux-Spanish crowd pleaser originally by Petipa (jazzed up by Gorsky)–is efficiently circusy, but largely without feeling. On June 1 it served as an ideal showcase for the Bolshoi Ballet’s young wonder, Natalia Osipova, who is gradually building a guest-artist relationship with the company.

Forget Cervantes: Natalia Osipova and Jose Manuel Carreño in ABT’s Don Quixote

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

As Kitri, the heroine of the piece, she made a flamboyant leaping entrance, slicing the air before her, sailing through it as if aided by a tail wind. Incredibly–I guess you had to be there, to see it for yourself–the afterimage she left wasn’t at all assertive but rather buoyant and fleecy.

As the ballet progressed, Osipova repeatedly displayed her uncanny balance, perching on point on one leg while her free leg proved to be equally comfortable flung up high as if reaching toward the heavens, stretching to the side like an implacable road sign, or curved behind her, parallel to the floor. No matter what extravagant sculpted shape the choreography demanded, she remained poised, relaxed but unmovable, for seconds that seemed like forever.

If this weren’t enough, she proved again and again that she has the gene for turning. Either you’ve got it or you don’t; Osipova’s a human gyroscope. In her rendition of the third act pas de deux, often given alone as a party piece, her execution of the infamous 32 fouettés (fierce whipping turns rooted to a single spot) suggested that the feat might well be retired until a new generation of dancers beats her alternating double whirls with singles–all produced with an aplomb suggesting she could probably up the ante to 64.

Interestingly, while most ballerinas play Kitri as a soubrette, Osipova, with her prodigious energy and her lack of sensual allure, made her a hoyden. When she hurls herself cross-stage, as horizontal as a flying bullet, confident of landing happily in her partner’s arms, you see that daring is her sole charm. She’s as brave as they come. And she could count on the catcher–Jose Manuel Carreño, playing Basilio, Kitri’s Mr. Right.

Carreño had splendid feats of his own to display, the most marvelous being multiple pirouettes from a single preparation in which the pointed foot of the working leg snakes down from the knee to the ankle of the rotating leg and, by the final turn, has the toes tracing a circle on the floor, like the pencil of a compass.

Still, so much about Carreño’s appeal as a dancer comes from his personality: the sweetness, the modesty; the undercurrent of erotic possibility; the masterly partnering that’s based on a keen awareness, at every moment, of his ballerina’s needs. His temperament shows up in all of his roles. It’s perfect for dancing Basilio with an electrifying technician goading herself on to even greater achievement. Carreño doesn’t try to dominate Osipova or compete with her; he enables and sustains her. His Basilio seems to be saying to this Kitri, Everything I do is for you.

Subsidiary Players:

Daniil Simkin–small, blond, and bare-chested–hit the air like a hand grenade in the Gypsy Camp scene that opens Act II. His role provides theatrical contrast to the romantic atmosphere of an exotic world at twilight. Simkin delivered ballet steps expanded, phenomenally, as if by an Olympics-grade gymnast. The effect was stupefying, thrilling, and grotesque.

Tiny, precise, and swift, finger coyly crooked to chin, traveling cross-stage with bourrées like a string of seed pearls, Yuriko Kajiya stole the Vision Scene as Amour (Cupid). The crispness of her dancing helped her avoid the cuteness endemic to this cameo role.

Victor Barbee, ABT’s Associate Artistic Director, enhanced the entire production with his intelligent portrayal of Quixote–a frail, tattered old man undaunted in the pursuit of his ecstatic visions.

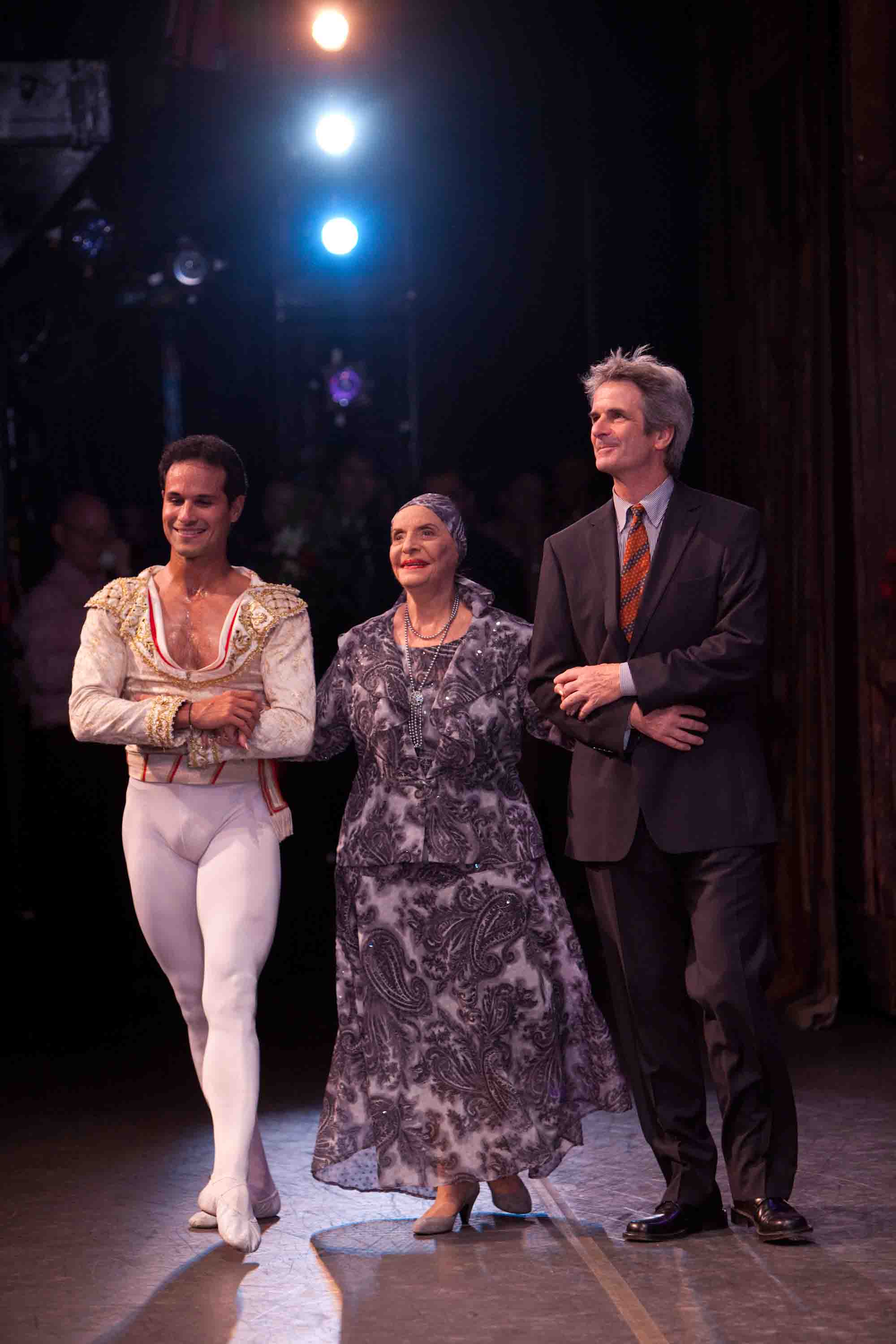

Grande Dame: Alicia Alonso, flanked by Carreño and McKenzie

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

Don Q was performed again on June 3 for Alicia Alonso’s 90th Birthday Celebration with a different pair–Paloma Herrera and Marcelo Gomes, Xiomara Reyes and Herman Cornejo, Osipova and Carreño–leading each of the ballet’s three acts. The Cuban-born Alonso, who blended sizzling technique with dramatic power and lyric eloquence, became a star of Ballet Theatre and then returned to her homeland to found the National Ballet of Cuba. Her dependence on the support of Fidel Castro gave her American admirers political qualms and her own uncompromising dictatorship over the company she brought into being against all odds frustrated the younger generations of dancers she bred. Still, she was a great artist and a woman of amazing courage, working half-blind through most of her career and dauntlessly pursuing her seemingly quixotic vision of a Cuban base for classical ballet. The dance world owes her a tremendous debt.

The celebration opened with a recent filmed interview interspersed with photos going back to Alonso’s childhood and film clips of her clearly remarkable dancing. The interview, which occasionally caught her close to tears, is filled with potent one-liners. Obeying medical advice on healing the detached retinas that ravaged her sight, she recalls, “I spent one year in bed, and I danced with my mind.” She refers to ballet as “the thing I love most in my life” and concludes with a rhetorical question: “Don’t you think that beauty and happiness of life is better to fight for than war?”

The film was followed by Alonso’s rising in the auditorium’s center box to accept the audience’s standing ovation. When the performance concluded over two hours later, Carreño and McKenzie escorted her onstage. There she received a lavish bouquet; the applause of the ballet’s entire cast, which had assembled behind her (leaving a respectful gulf of space between them and her); and a gentle shower of confetti wafting down from above. She wore the most ravishing evening dress–all filigreed steel gray and the palest of blues–somehow glinting in the bright light that was beamed at her. The most powerful women in Europe and the Americas would do well to ask her the name of her dressmaker.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

Thank you so much for your analysis of “Estancia.” I thought something was wrong with me, the only unhappy kangaroo among the cheering spectators. I wondered if your dance reviews or writings on dance have been published anywhere.

Tobi,

Your descriptive language is so wonderful here. For example: “Stupefying, thrilling, grotesque”! I know exactly what you mean. If only those American kids at the Bolshoi Ballet school could read that . . . sigh.

And your bullet points on Wheeldon’s new work . . . here in Frankfurt, dance dramaturgy is normal. Maybe what we need is an American dramaturgy…

Jeff

I totally agree with your comments on Christopher Wheeldon’s new piece, “Estancia,” and Neumeier’s “Lady of the Camellias.” As to the latter, Frederick Ashton did it better and shorter in “Marguerite and Armand.” However I actually went to NYCB on May 29 to see the two Balanchine pieces, “Danses Concertantes” and “Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet.” I thought even if the performances were not so hot, I could see the rarely revived “Danses Concertantes” with the Eugene Berman decor and costumes and “Brahms-Schoenberg” with the exquisite Karinska costumes. However both were very well performed that evening. I think Wheeldon is a talented choreographer, but this particular program showed that Balanchine is still the master.

Thank you, thank you, thank you. I am a former New York resident and unabashed balletomane. I now live in Shanghai where ballet presentations are few and almost always consist of “Swan Lake” performed by ersatz groups of Russians purporting to be the “best.” Your writing gives me so much pleasure, as does your knowledge, taste and unerring eye for beauty. I was one of the multitude who lamented your departure from New York magazine. Thank goodness for the internet! Your Ballet Diary is a treasure—once more, thank you.

Dear Myra Malkin,

Thank you for writing. SEEING THINGS is enlarged by its readers’ comments.

You ask if my dance writing has been published anywhere. If you mean in print, the answer is yes: I was the dance critic for New York magazine for 22 years and, before that, wrote regularly for Dance magazine. I’ve also written for the Village Voice, the New York Times, and so on. But if, by “published,” you mean in book form, the answer is no, apart from anthologies and the like. My books include some two dozen books for children and, for adults, “Obsessed by Dress,” a meditation on clothes.

With best wishes,

tt

Tobi, thanks for saving me from “Estancia,” but I liked “Lady of the Camellias.” I think I saw it years ago with Marcia Haydee. I found the first act of this production boring, but after that, I was totally absorbed. Maybe it’s because Neumeier was a classmate of mine at ballet school at Stone-Camryn in Chicago more than 60 years ago that I forgive his excesses. Keep writing. Judith Schwantes

“Estancia” and “Camille” are entertaining, but in different ways. The latter is supposed to be a tear-jerker and thus requires characterful dancers, but the choreography is second-rate. The former tells the tale more effectively. It’s Socialist Realism from the Popular Front era.

Osipova is amazing in her jumps (also in speed and lightness), but is not an artist yet. I had a bad seat, and missed her “Giselle” excerpt, but saw her “Sylphide” last year. The Russians still seem to have the best training by far.

“Estancia”: Yes, it reminded me of Agnes de Mille, but also of Loring’s “Billy the Kid” in the use of its populations.

The “Manon” element of “Lady of the Camellias”: the Abbé Prévost’s novel was popularized as much, perhaps mostly, by Puccini’s “Manon Lescaut” as by Massenet and MacMillan.

Dear Tobi:

It is so gratifying to read your reviews. They are clear, cogent and incisive. They also make me think of issues fermenting in my own mind and in my dance-making.

I remember Kitty Cunningham (Ballet Review until its demise), who had known me since my late teens, saying that I should feel lucky to have choreographed a wide range of works not under the radar of the New York City reviewers. In her words, “We are on the look-out for that genius and on someone’s third work we anoint them as the next Byron of dance. So they get too many commissions, and ten works later we find them wanting, or feel they keep churning out the same things again and again.”

I imagine that fame is hard to resist and good at least for the dance-makers who are on the A-list.

Michael Mao will be happy, I think, to know that Ballet Review isn’t “demised” any more than Kitty Cunningham is. Watch for the Spring 2010 issue of BR any day now, but Kitty hasn’t written for a long time.

Well, well, well, I watched “Estancia” and the house went wild. For a 37-year-old kid to take such a score and do a pretty good job is not bad! I think Mr. B was afraid of it since the music is pretty juicy, loud, melodic, and merry. I would give it a B- but again the kid is learning and let’s not forget that not all that Mr. B or even Martha Graham did was that great. Again, Mr. B was very lucky to have Stravinsky and Lincoln K. as friends. So my kudos to Wheeldon for having the audacity to pick this score. Gracias!