Ballet Diary No.8: New York City Ballet: Darci Kistler Farewell; Peter Martins’s Mirage; Melissa Barak’s Call Me Ben, Maurice Kaplow’s Farewell (NYCB’s season at the David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC, closed on June 27)

Note: This is No. 8 in the series “Ballet Diary”–comments on the 2010 spring seasons of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, along with related performances. To read previous pieces in the series, click here: No. 1; No. 2; No. 3; No. 4; No. 5; No. 6; No.7. The completed “Ballet Diary” series will comprise nine essays.

Darci Kistler was the last ballerina to capture Balanchine’s imagination, and she had a packed, loving house for her farewell performance on June 27 after 30 years with the New York City Ballet.

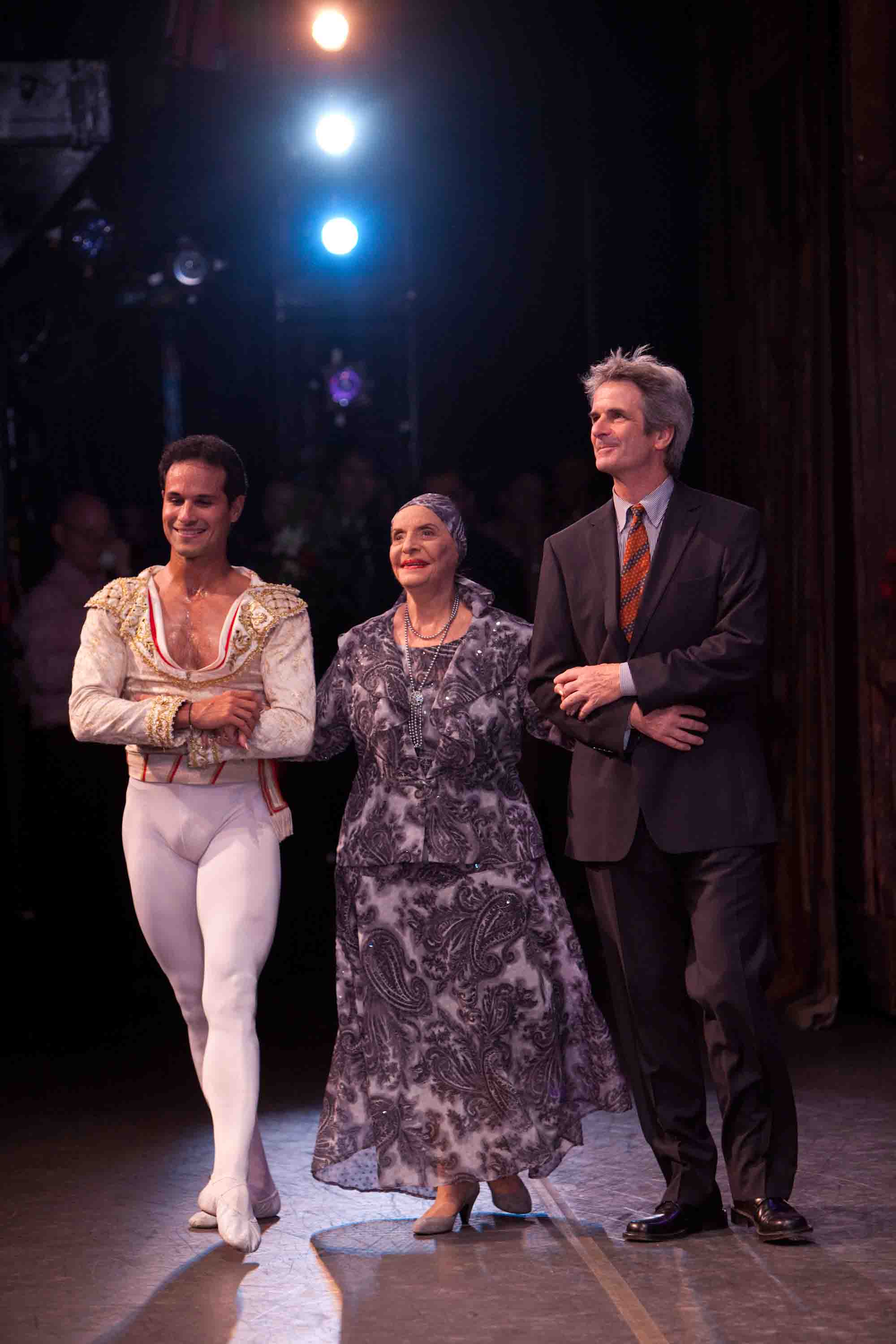

Swan Song: NYCB’s Darci Kistler; directly behind Kistler, in the long turquoise dress, Kistler’s and Peter Martin’s daughter, Talicia; to the right, in a dark suit, Martins

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Kistler grew up in California with four elder brothers, a situation bound to contribute to her physical prowess and her derring-do. She completed her dance training at the School of American Ballet, entered City Ballet at the age of sixteen and was made a principal dancer only two years later. I saw her first at the annual SAB Workshop Performances–a marvel both as a frisky adolescent in a Bournonville duet (even the air surrounding her seemed fresh), and the next year as an entirely credible Odette in Balanchine’s one-act version of Swan Lake. Even then this ebullient teenager, given to rakish street clothes, had an instinct for feeling that allowed her to access the poetic plight and tragic destiny of the Queen of the Swans. Balanchine, who hoped to avert her modeling her interpretation on that of an established ballerina–that is, being anything other than herself–suggested that she visit the zoo to observe the swans; she did.

I recall watching Kistler in Antonina Tumkovsky’s advanced women’s class at SAB. In the last third of the session, according to custom, these uncannily accomplished adolescents divided into two groups to take turns doing combinations of movement that traveled–hurtled is more like it–across the studio floor. The “resting” dancers were expected to stand quietly in the background, catching their breath and giving their muscles and tendons a break, at most marking the challenging combinations with their hands, But Kistler would dance, full-out, with both groups. Tumey, as generations of SAB students called her, shook her head in admonition, while the expression on her face revealed the pleasure she took in this prodigy.

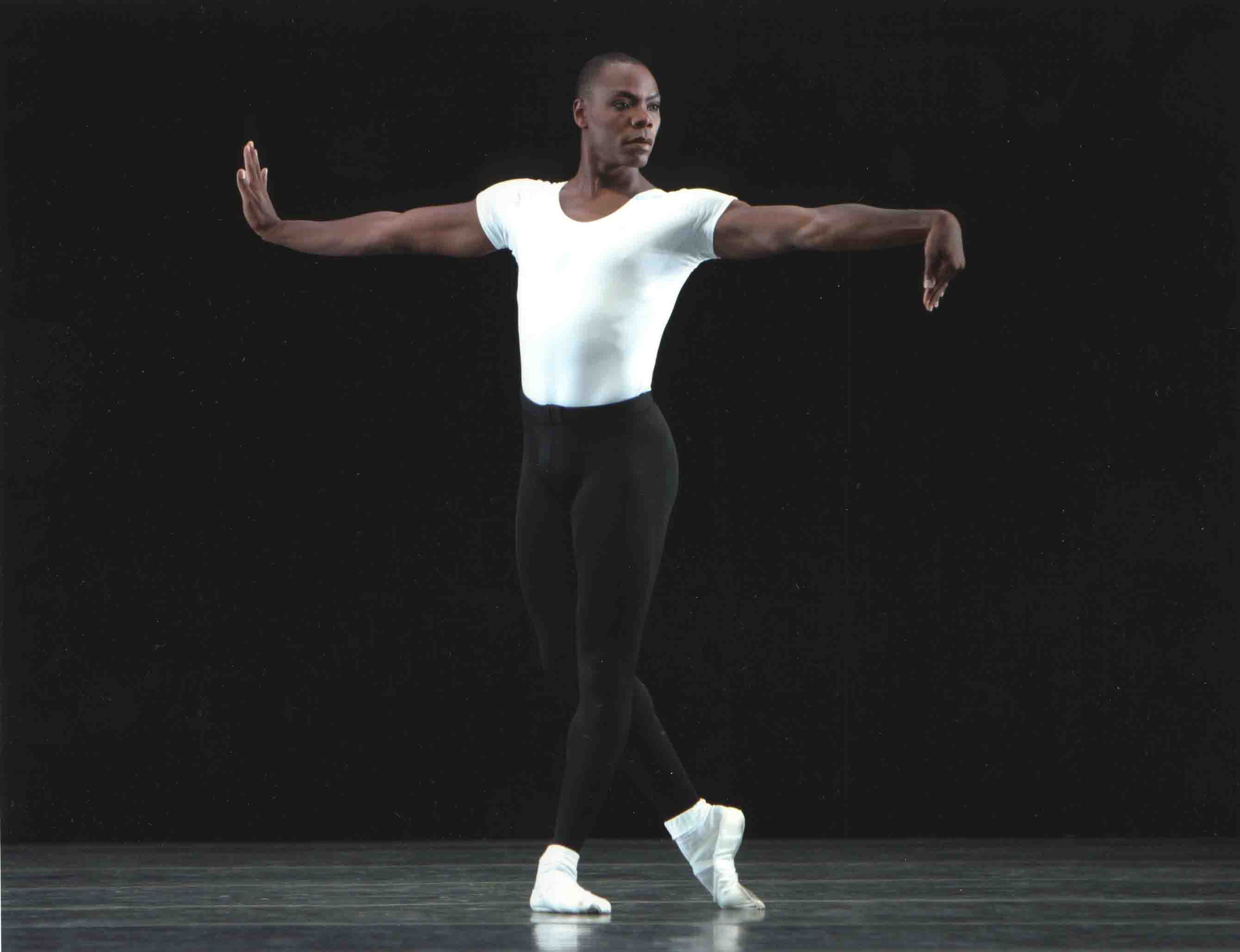

Pure Movement: Kistler and Sébastien Marcovici in Balanchine’s Movements for Piano and Orchestra

Photo: Paul Kolnik

In the prime of her career Kistler was unquenchable: athletic, infinitely musical, radiant–and, where appropriate, so genuinely sweet that she was never cloying. The moment she stepped on stage it was impossible not to watch her. The most technically demanding choreography never fazed her. She seemed to be fueled not simply by the determination that lies behind most stardom but by her sheer delight in dancing.

Early on, however, Kistler was felled by injury and a failed surgical attempt to address it, from which she never completely recovered. This despite the patient, heroic efforts of her most important mentor, SAB’s Stanley Williams. One day Kistler, whom I know only slightly, remarked to me about living with incapacity, “I have a little bit of a handicap in there now, but I always think of it like–well, a horse can run beautifully with reins on it, too.” (Moved by the pathos of her tone and the courage of her attitude, I wrote her words down.) Much later, surgery for a back problem tamed her even further. Slowly but inexorably, her once-glorious technique diminished. Determined–unstoppable, I’d guess–she continued to perform.

Love Is Eternal: Kistler with Jared Angle in Swan Lake

Photo: Paul Kolnik

As Kistler’s career began, so it concluded–with Swan Lake, this time in the final section of the full-length version of the ballet, staged by her husband, Peter Martins. Nearly all she had left at this point was her innate gift for riveting a viewer’s attention and the ability of an actress who, in her maturity, can offer a deeper, more complex portrayal of character and situation because she has known something of life. Somehow, on this occasion, that was almost enough.

Earlier in the farewell program, Kistler was the unnervingly shaky center of a pair of abstract Balanchine works, Monumentum pro Gesualdo and Movements for Piano and Orchestra. Then she illuminated the stage with the scene from the master’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream in which, as Titania, Queen of the Fairies, she falls in love–as a child might, given a marvelous toy–with the uncouth workman, Bottom, magically transformed into an ass.

Those ready to say “She should have stopped earlier” are right, as Kistler’s most ardent fans themselves admit, a few of them going so far as to confess that the performances of the late-career Kistler threatened to erode their memory of Kistler in her youth and Kistler in her prime. However they’re not factoring in the possibility that, given this ardent ballerina’s hunger for performing, she may simply have been unable to stop. Aficionados with long memories will recall that a relentless avidity for the stage has characterized some of the most unforgettable dancers–in both the classical and modern camps: Margot Fonteyn, Rudolph Nureyev, Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham. Artists, like ordinary folks, are only human.

As for the curtain calls at Kistler’s farewell performance, they were just as you can imagine. Only more so.

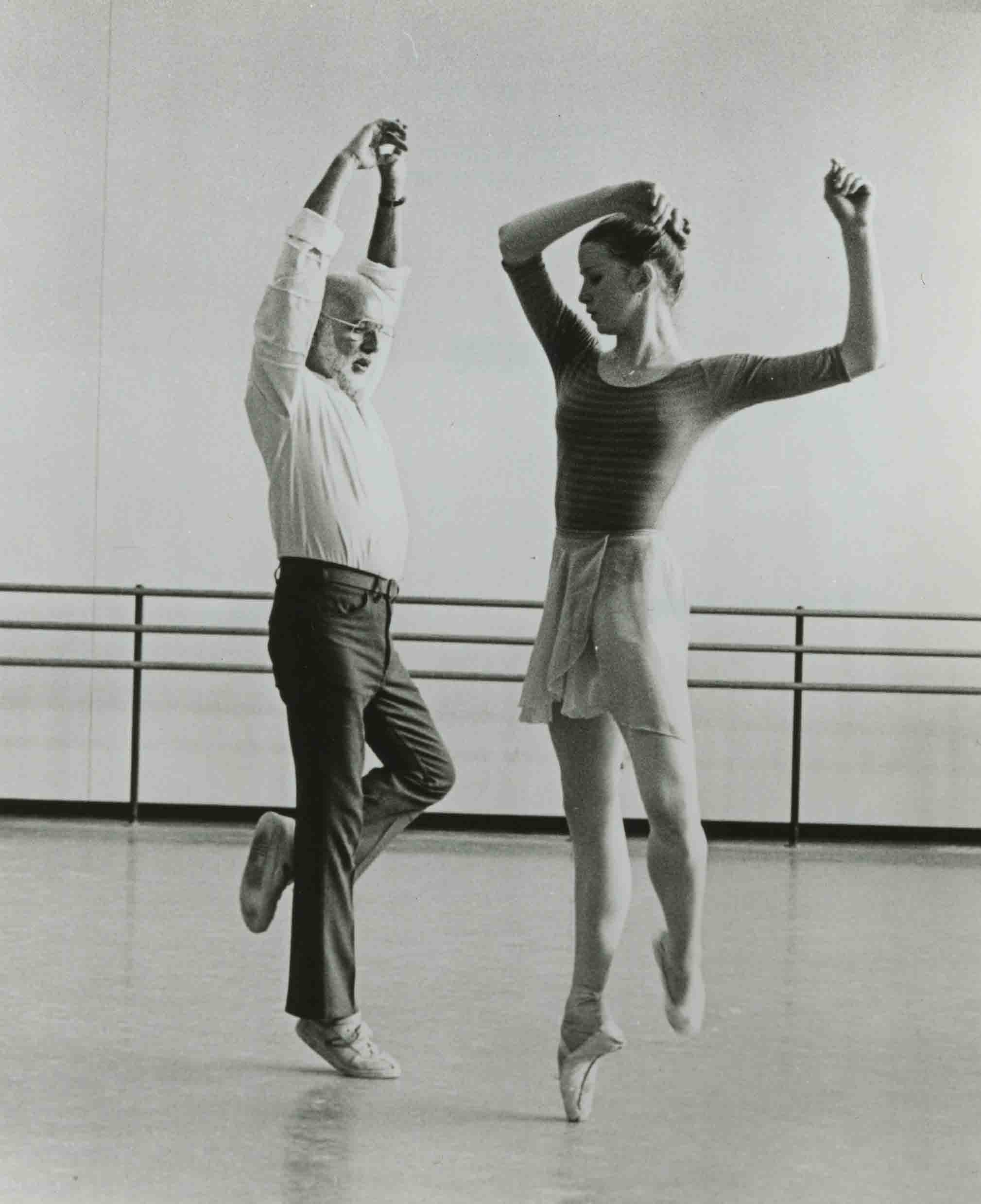

Back Then: Kistler working with choreographer Jerome Robbins

Photo: Carolyn George

Peter Martins’s Mirage, the last to appear of the seven ballets created for New York City Ballet’s Architecture of Dance festival, was given its premiere on June 22. Despite truly handsome dancing, it looked engineered rather than choreographed, with sterile results.

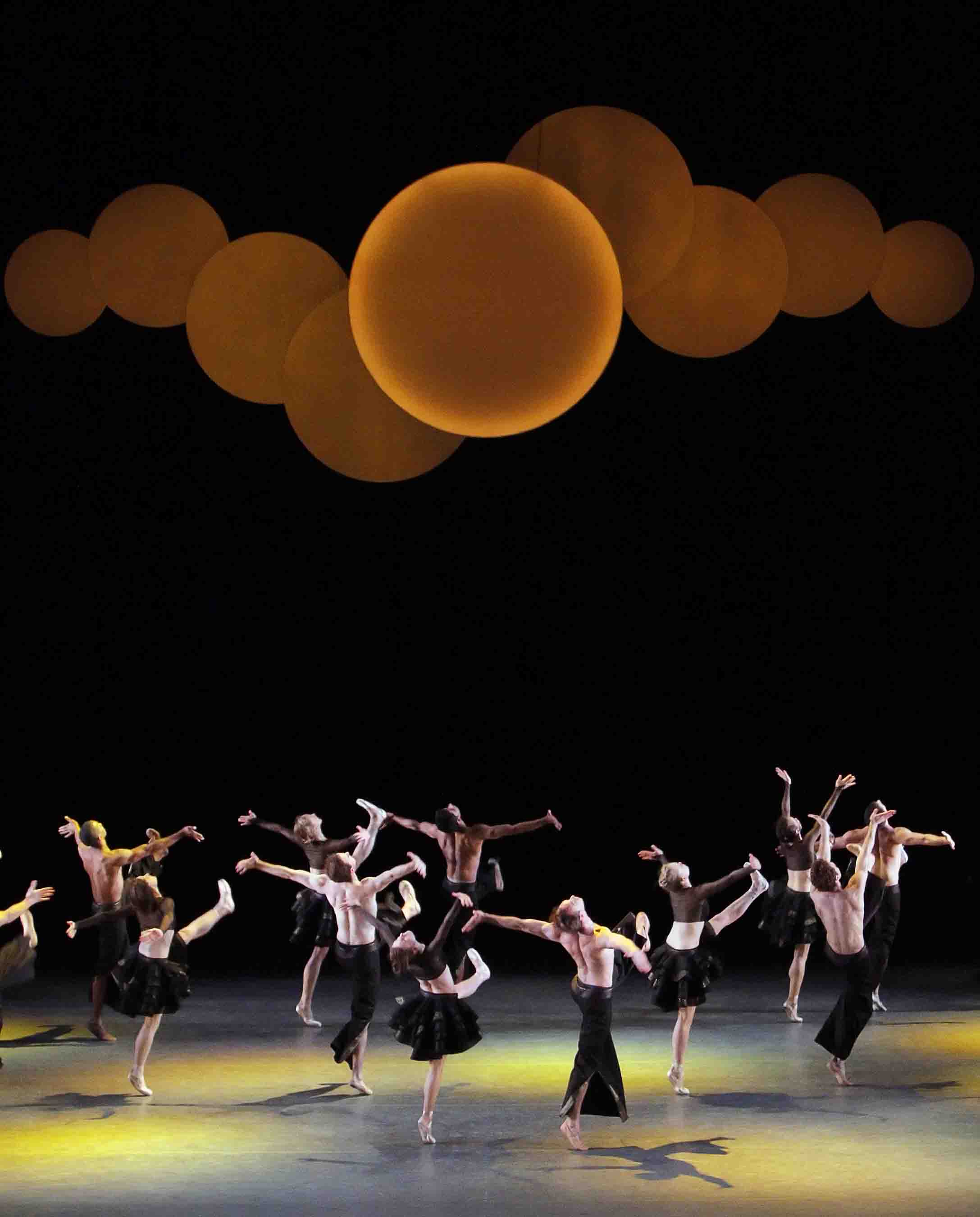

Architecture of Dance: Calatrava installation hovers over full cast of Martins’s Mirage

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Martins moves three principal couples and four secondary pairs in stark geometrical patterns–everyone dressed in Marc Happel’s sleek, chic practice clothes of gray and black. The dancers might be the instruments of a puppeteer operating with a prepared chart; they reveal neither personality nor spontaneity. The choreography looks like a highly efficient demonstration of selected skills that are honed by classical dance training, among them sheer power assiduously kept under control and extreme flexibility in the joints, which permits the leg to point to the heavens. The dancing, although understandably monotonous, had a stunning, clear-cut beauty, but nothing about the choreography stirs your mind or touches your heart; indeed, it has faded from your memory by the time you get home.

The ballet’s score, Violin Concerto, was commissioned from the Finnish composer Esa-Pekka Salonen, who conducted it at the premiere. The adroit guest violinist was Leila Josefowicz. While I found the music intriguing, I couldn’t fathom how the dancing connected to it. But then I couldn’t understand–and not for lack of trying–how any of the production’s elements related to the ballet’s title.

An installation by Santiago Calatrava, essentially the architect-in-residence for the season, served as the décor. Hung high above the dancers’ heads, it consisted of two half ovals–think of reading spectacles–that overlapped just slightly. The shapes were filled with thin parallel strips that formed moiré patterns with changes in the angle at which the spectator viewed them. The piece moved gently up and down a little ways and folded slightly in and out as if inspired by origami tactics. For its grand finale it was splashed with variously colored light. This last effect, I believe, was what my mother used to call “a lapse of taste.”

I finally caught up with Melissa Barak’s new ballet, Call Me Ben, commissioned by the City Ballet’s Architecture of Dance festival, and it’s as dispiriting as colleagues and friends who went earlier have been saying. The audience seemed to think so too, judging by its tepid applause.

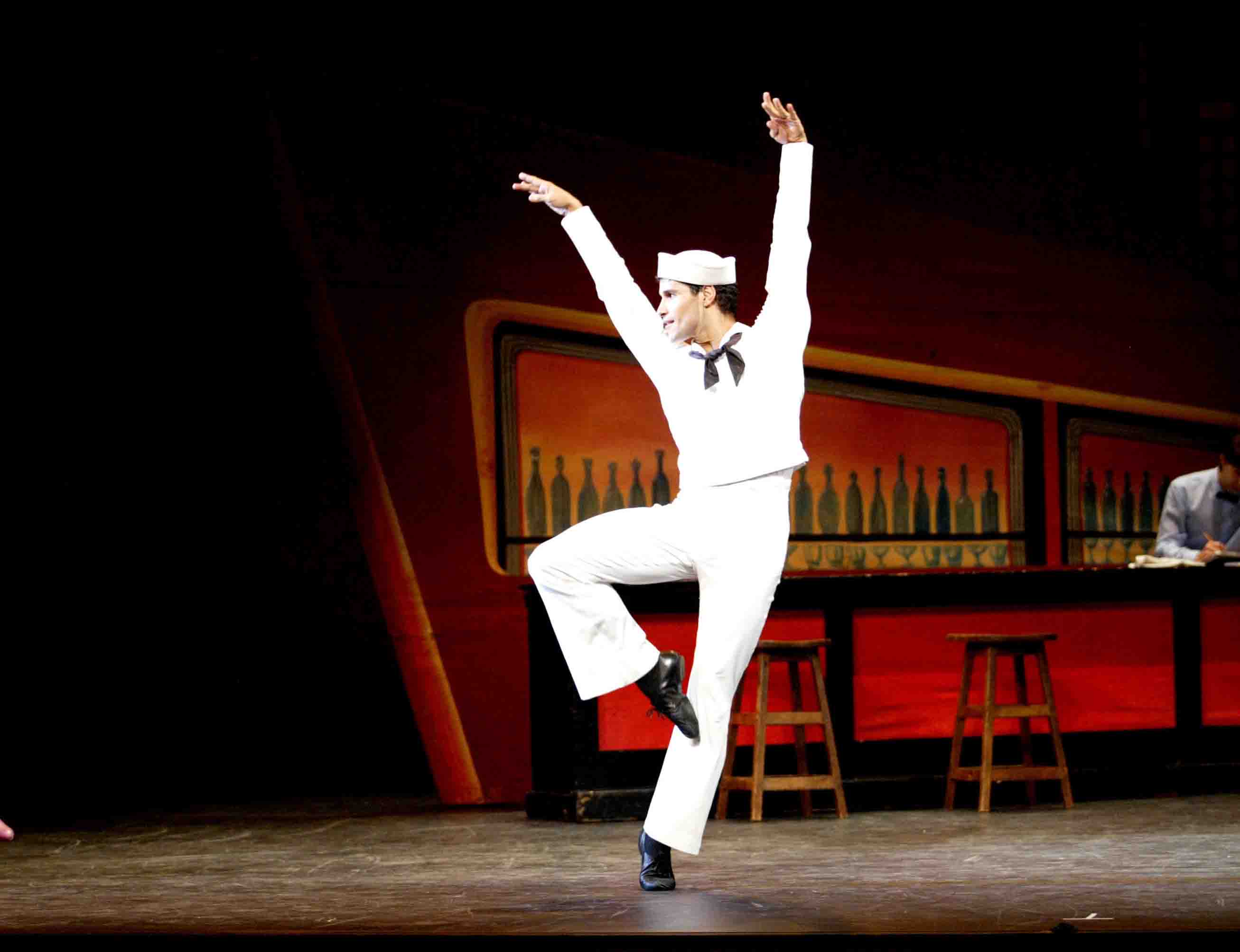

Dressed to Kill: Daniel Ulbricht, Jenifer Ringer, and Robert Fairchild in Barak’s Call Me Ben

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Barak is a City Ballet alum, now dancing with Los Angles Ballet and choreographing steadily. She has already done a few pieces for her alma mater and its school, which were pleasant but hardly rigorous–not a strong argument for hoping she’d help correct today’s dearth of female classical choreographers. Call Me Ben is bigger and punchier than her earlier work, but pretty much a disaster.

It purports to tell the story of Benjamin (“Bugsy”) Siegel, the legendary gangster with extravagant dreams, credited with inventing Las Vegas and rubbed out at 42 by a gunman who remains unidentified. To get the colorful tale across, Barak resorts to having the dancers talk (almost always a mistake, because they’re not actors and they’re out of breath). Only Robert Fairchild, playing the antihero, manages his lines without sounding like a raw teen in the annual school play. The lines themselves, by the choreographer and company dancer Ellen Bar, are puerile.

The dancing Barak choreographs is efficient but innocuous and does nothing to advance–or even tell–the story. At best, it recalls routine stuff made for Broadway musicals half a century ago. Indeed, you expect the cast to burst into song at any moment. I kept wondering if the piece wasn’t meant to warm up City Ballet followers for the new Susan Stroman creation announced for the company’s winter season.

Barak may have been thinking of Balanchine’s Slaughter on Tenth Avenue, to say nothing of Agnes de Mille’s ensemble work in musical comedy, but to “borrow” so blatantly from Kurt Jooss (for sinister moves around a long conference table) was surely a miscalculation.

Call Me Ben boasts a score commissioned from the wunderkind Jay Greenberg; it seemed to be doing what it was supposed to do, with more panache than the choreography could muster. Santiago Calatrava provided two mediocre painted backdrops, both dominated by palm trees. The best parts of the “décor” were Jenifer Ringer (delectable in the way sweethearts used to be) as Bugsy’s shady No. 1 mistress, Ringer’s tailored suit (which any woman in her right mind would kill to own), the men’s fabulously cut suits in ogle-worthy fabrics, some of the women’s filmy dresses (costumes by Gilles Mendel), and the women’s Forties hairdos. All this must have cost a mint.

June 24th saw another NYCB retirement, not in the Sunday series of dancers’ farewells, but this time of the company’s veteran conductor, Maurice Kaplow. A ballet conductor is usually buried in the orchestra pit, his back to the spectators, except for pro forma bows. On this occasion, given several opportunities to reveal himself to the audience face to face, Kaplow appeared to be the most benign of gentleman–modest, yet radiating joy.

Fond Farewell: Veteran Conductor Maurice Kaplow fêted by the team he served

Photo: Paul Kolnik

He has been with the company for 20 years and helped rescue the musical ensemble from a dismal period in the early 1990s. Kaplow, who is also a violinist, composer, and teacher, is apparently a master of harmony in his home life as well; a press release about the man the public rarely notices makes a point of noting that Kaplow was also celebrating the 50th anniversary of his marriage, which has given him three sons and five grandchildren.

The first ovation Kaplow received from the audience came when the orchestra, in a bit of magical engineering, was raised from the pit to visible level–just like that organist at Radio City Music Hall–to play the overture to Carl Maria von Weber’s Euryanthe under his direction. Then, after he’d led his musicians in accompanying Peter Martins’s Barber Violin Concerto and Balanchine’s Western Symphony, Kaplow appeared onstage for a solo bow beside a free-standing floral arrangement (surely a communal offering) while the audience rose to its feet, clapping like mad.

Next the ballerinas of the evening arrived to fill Kaplow’s arms with bouquets, followed by the members of the orchestra, each, in high spirits, tucking a single rose into the bouquets he already held, until the man himself nearly vanished from view.

Then Darci Kistler crossed the stage to present Kaplow with a single rose, curtsying deeply to him. Apart from that tender, solemn moment, the prevailing mood was one of affectionate gaiety. Peter Martins added to it by pulling out a baton and “conducting” the musicians in a rendition of “Happy Birthday,” to which the instrumentalists sang simultaneously, joined by the audience. What more was there to do but let scads of multi-hued confetti flutter down to create that tiny theatrical marvel, a tinted snowstorm in summer.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias