Ballet Diary No. 1: Introduction to Ballet Diary series; New York City Ballet: Opening night gala / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / April 29, 2010

Year after year New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, the kingpins of classical dance here in the States, insist upon competing with each other at Lincoln Center. As springtime slips into summer, the two troupes play mostly overlapping seasons–this year, eight weeks each–at abutting theaters (City Ballet will be at the David H. Koch, April 29 – June 27; ABT, at the Metropolitan Opera House, May 18 – July 10). How’s a dance critic to cope? Perhaps taking the easy way out–though any other arrangement I devised seemed artificial–I decided that this year I’d cover the scene with a ballet diary, describing and commenting on the lavish procession of events weekly or bi-weekly. Let’s hope this works. No aspect of a life in or near dance comes with a guarantee.

With its opening night gala on April 29, New York City Ballet inaugurated a blockbuster eight-week season. Under the umbrella title of “Architecture of Dance: New Choreography and Music Festival” and honoring the 50th anniversary of Lincoln Center, it will present seven new ballets, five of them using decor designed by the distinguished architect Santiago Calatrava.

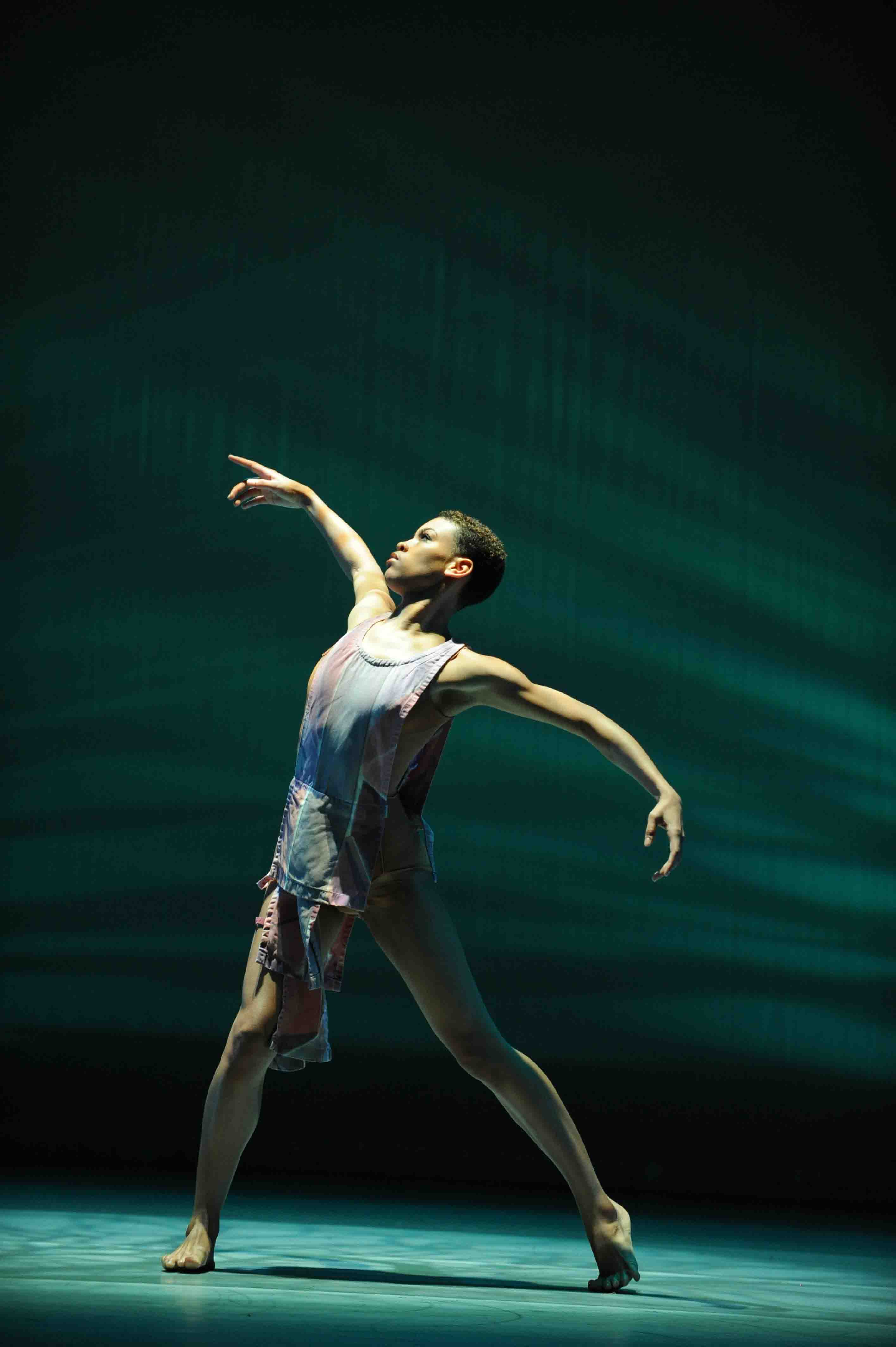

Santiago Calatrava’s set for Benjamin Millepied’s

Why am I not where you are, one of the seven new works in New York City Ballet’s “Architecture of Dance” festival

Photo: Paul Kolnik

The commissioned choreographers are Alexei Ratmansky (working to a score by Édouard Lalo, world premiere April 29); Benjamin Millepied (commissioned score by Thierry Escaich, April 29); Wayne McGregor (score by Thomas Adès, May 14); Christopher Wheeldon (score by Alberto Ginastera, originally commissioned by Lincoln Kirstein, May 29); Melissa Barak (commissioned score by Jay Greenberg, June 5); Mauro Bigonzetti (commissioned score by Bruno Moretti, June 10); and the City Ballet’s ballet master in chief, Peter Martins (commissioned score by Esa-Pekka Salonen, June 22).

The season looks both forward, with these new works, and backward, with farewell performances for Yvonne Borree (June 6); Philip Neal (June 13); Albert Evans (June 20); and Darci Kistler (June 27, which marks the closing of the season). All the farewells are 3:00 Sunday matinees, so diehard fans can bring their children, urgently whispering to them as the curtain rises, “Remember this.” Needless to say, the strategy probably won’t work. (I took my then very young daughter to see Margot Fonteyn toward the end of her career; though already hooked on ballet, the child didn’t recall the performance even the next day.) Nevertheless, adults often enjoy their effort to provide a youngster with material for future nostalgia. I did. And still do.

Well, the gala opening night program began not with dancing but with a video, explaining and illustrating the “Architecture of Dance” concept, which, truth to tell, feels more like branding than an artistic vision. Created by Kristin Sloan, a former City Ballet dancer, this canned introduction was a string of all too brief takes, moved along so speedily as to be almost beyond comprehension to anyone not reared on video games. It featured personable chat from Calatrava and Martins as well as other collaborators in the venture and footage of the dancers in rehearsal. It was succeeded by the live presence of Martins, standing before the golden bronze stage curtain to toast Calatrava and his wife, picked out by a spotlight from where they were seated in the First Ring. The gesture was rather dry; only the special three got to drink.

When the curtain finally rose to reveal Calatrava’s stage design for the Millepied ballet, Why am I not where you are, it certainly let the air out of any balloons of anticipation. Calatrava is known not merely as an architect, but also as an engineer, a sculptor, and a painter. Although this is his first venture into design for dancing, he seemed to be just the right guy for the job. His freehand sketches, in what looks like an oily chalk, for the season’s prospectus aptly suggest movement in space and, where the human body is concerned, if not originality at least the savvy taste to have chosen Rodin (who captured Isadora Duncan so effectively) as a mentor.

In the end what the Millepied ballet got was a huge, imposing structure very much in the style of Calatrava’s striking buildings. It’s a silvery double arch, one section brooding over the other. The two are joined by slender parallel rods, creating an environment that lends mystery to the dancers when they move behind it, becoming half hidden, though still certifiably visible. The inner arch hovers over empty space, which registers as a dusky cave through which dancers can enter the unblocked, brightly lighted part of the stage in which the more fevered action occurs.

Santiago Calatrava’s set for Benjamin Millepied’s

Why am I not where you are, one of the seven new works in New York City Ballet’s “Architecture of Dance” festival

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Millepied deals with the situation dutifully, but not imaginatively, though he says in a brief interview for the house program that the relationship between his choreography and the architect’s structure was a collaboration between him and Calatrava. By the end of the one-small-page Q&A, the choreographer is telling a somewhat different story: “It’s a large sculpture that sits on the stage, so I had to incorporate it into the choreography.”

The choreography itself reflects the attempt by a number of younger classical-dance makers to overcome the sterility they find in today’s ballets. They believe this arid state is the result of several decades’ overemphasis of abstract dance. These choreographers rarely blame Balanchine directly–and it would be hard to sustain the argument that Concerto Barocco, The Four Temperaments, Agon, and Symphony in Three Movements are sterile. But today’s classical choreographers do miss the presence of feeling that they think narrative and character brought to a dance. Since they reject “story ballets” from Petipa to Tudor as being, as it were, “so yesterday,” they’re trying to devise choreography that will touch the heart without reliance on plot. I would quibble with their logic, yet I’ve got to admire their effort to do something about the frustrating situation in which they find themselves.

Millepied’s Why am I not where you are works by demonstrating feeling–something he’s not naturally good at–in tiny passages, sometimes mere phrases, in between which he reverts to objective stuff. I thought his piece was specifically “about” something–a soulful man who stands outside the group that dominates his society (he’s just not a frat boy, if you will), who succumbs to the temptation to give up his real self in order to join that group, and is thus doomed to disaster. In his case he loses the young woman destined to be his soul mate, though she never gives any indication that she is (she seems to be a typical sorority girl–one of the “In” crowd) before it’s already too late. When I proposed this interpretation to a colleague, however, she looked at me doubtfully and said, “Really?”

The music for Why am I not where you are was commissioned from Thierry Escaich. French like Millepied, Escaich is the noted organist and composer in residence for the Orchestre National de Lyon. His score, The Lost Dancer, proposes shifting emotions–threat, excitement, fear, exhilaration, despair. It is full of possibilities.

In his Namouna, A Grand Divertissement, Alexei Ratmansky addresses the same issue Millepied tried to resolve, but then he usually does, and never seems to find it a problem. A significant part of this choreographer’s profile is a love and respect for the old, so he often borrows from the devices of eras past, typically giving them a fresh life that makes them seem contemporary–that is, contemporary, but with marvelous ancestors.

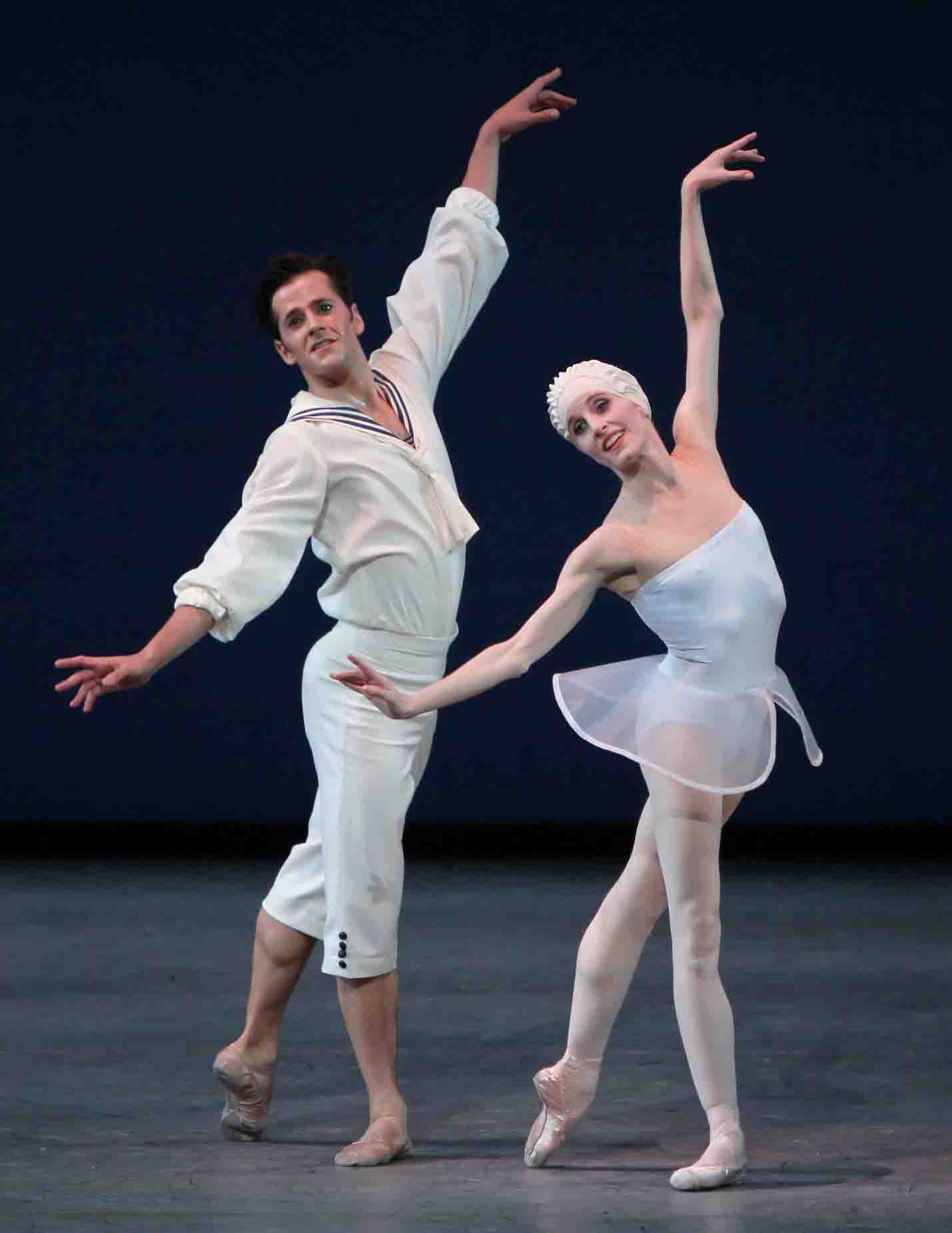

Wendy Whelan and Robert Fairchild in Alexei Ratmansky’s Namouna, A Grand Divertissement, one of the seven new works in New York City Ballet’s “Architecture of Dance” festival

Photo: Paul Kolnik

Namouna takes brilliant advantage of the riches of nineteenth-century ballet–the Russian school of that period, the French school, and the Danish school (that is, the Bournonville school), which reshaped the French principles and held on to many of them to this day. Ratmansky, who was trained at the Bolshoi Ballet’s academy and returned to head the company for several years, to say nothing of doing a stint with the Royal Danish Ballet, evidently absorbed everything he was exposed to like a sponge. These delights–the mime, the dazzling details of the complex footwork, the major role assumed by the corps de ballet (sheer Petipa)–are all present and all transformed in Namouna.

An example of the transformation of the corps de ballet work, impressive enough in its old guise, with at least 16 dancers moving in unison in clear, simple geometric patterns, is enlivened for today by small, piquant deviations from unison activity without any loss of force. Complications of the patterns that enrich the original tactics are at once deliciously inventive and gently amusing. For instance, where the corps would shape up in straight lines, confronting the audience head-on, Ratmansky says to himself, Why not put the lines on the diagonal? Where you have a large number of gorgeous bodies costumed alike, why not vary the number of bodies in each line? Just about all his variations of this nature are clever and endearing–even to viewers who know little to nothing about the original conventions.

Ratmansky’s music for this ballet is Édouard Lalo’s Namouna, made for a 19th-century French ballet. His “scenic investiture” is, unlike Calatrava’s attention-riveting constructions, no more than a backdrop that accepts the projection of light in colors that vary with the mood of the moment. The dance is unconscionably long, yet never repetitious or boring. Its stars are Wendy Whelan, Robert Fairchild, Jenifer Ringer, and Sara Mearns.

Sara Mearns in Alexei Ratmansky’s Namouna, A Grand Divertissement, one of the seven new works in New York City Ballet’s “Architecture of Dance” festival

Photo: Paul Kolnik

These comments on the first two new ballets in the “Architecture of Dance” season are just a first impression, formed in the hectic gala atmosphere engendered by the patrons in the prime seats, who make generous contributions to the company’s coffers and for whom opening night is as much a social occasion as a theatrical one. I’ll have more to say after a second, calmer look when each work is given its first showing to the general public–the Ratmansky on May 5, the Millepied on May 22.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias